Joshua B. Hoe interviews Tawana Petty and Alex Vitale about policing and Operation Relentless Pursuit

Full Episode

My Guests

Tawana Petty is a mother, social justice organizer, youth advocate, poet and author. She is involved in water rights organizing, data and digital privacy rights education, racial justice and equity work. She is Director of the Data Justice Program for the Detroit Community Technology Project and is a convening member of the Detroit Digital Justice Coalition (DDJC)

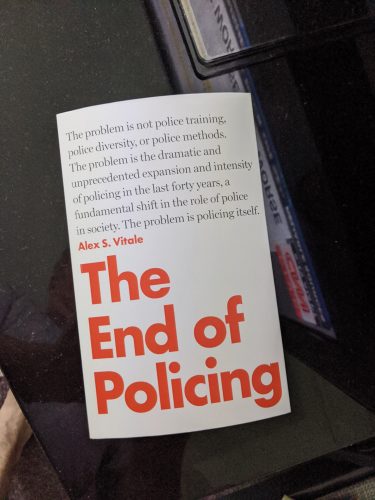

Alex Vitale is a professor of sociology and the coordinator of the policing and social justice project at Brooklyn College. He is also the author of the book “The End of Policing”

Notes from Episode 85

There were storms in the Detroit area during the recording, you will notice some anomalies from the microphones but we have done our best to reduce the impact in editing.

The Supreme Court recently decided not to give relief to our brothers and sisters in Florida who thought they earned the right to vote after the passage of Amendment 4. YOU can make a difference right now, if it is in your means, by helping pay down the criminal justice debt of someone in Florida #FreeTheVote

You can hear my recent interview with FRRC co-founders Neil Volz and Desmond Meade by listening to Episode 82 of the Decarceration Nation Podcast.

Some of the headlines I saw that were really problematic included (I am including the word “felon” only to demonstrate the headlines ugliness):

“Supreme Court deals blow to felons in Florida seeking to regain the right to vote” – Washington Post

“The Supreme Court refused Thursday to let Florida felons who have completed their sentences vote in an upcoming primary without first paying fines, fees, and restitution, as the state requires” – USA Today

The use of felony language is reductionist, totalizing, and reinforces the legitimacy of a widely used insult.

A more ethical headline, to me, is this one:

“The Supreme Court just stopped 1 Million Floridian’s from voting” – Slate

To read more about my feelings on this issue, here is an article I crowdsourced over a year ago.

There has recently been a spike in homicides across many major cities, the causes are far from being determined (regardless of the loud voices in the room). We know, the NYPD explanation is not truthful based on their own statistics.

Tawana suggested that 40% of COVID cases in Michigan happened in Detroit.

Water access is a huge problem in Detroit

AG Barr announced Operation Relentless Pursuit last December.

Here is a link to Alex Vitale’s website.

Tawana Petty wrote a powerful paper about Project Greenlight in Detroit.

Here is more on the story of Robert Williams and facial recognition technology.

There are three major articles/books referred to endlessly on the center-right of the policing debate:

The book “Bleeding Out” by Thomas Abt who discussed the book on this podcast during Episode 61 of the Decarceration Nation Podcast.

This article in VOX by Matt Yglesias

This article, “Why Do We Need The Police,” by Patrick Sharkey

Here is a link to more about de-identified federal law enforcement officers.

And let’s finish with a post-haircut COVID-era picture (sigh).

Transcript

A full PDF Transcript of Episode 85 of the Decarceration Nation Podcast.

Joshua B. Hoe

Hello and welcome to Episode 87 of the Decarceration Nation podcast, a podcast about radically reimagining America’s criminal justice system. I’m Josh Hoe, and among other things, I’m formerly incarcerated; a freelance writer; a criminal justice reform advocate; and the author of the book Writing Your Own Best Story: Addiction and Living Hope.

We’ll get to my interview with Tawana Petty and Alex Vitale in just a minute, but first, the news.

The Supreme Court came down this week on the side of the Governor of Florida, and against the formerly incarcerated potential voters in that state on the question of Amendment Four. I’m starting my own campaign to support an already existing campaign by the Florida Rights Restoration Committee to help people whose criminal justice debt is preventing them from voting in that state. My campaign is called Free the Vote and it will connect you to the FRRC account so that you can contribute money to help pay off formerly incarcerated Florida residents’ criminal justice debt. Let’s show the Governor of Florida and the Supreme Court majority that America stands for voting and against disenfranchisement. I will include links in the show notes and everywhere else on my social media, etc. I will be giving money to this cause – I already have – and I hope that you will be giving money too. In fact, what I’d really like is for everyone who gives money to send the following message on their own social media:

“I just helped #FreeTheVoteinFlorida” and if you can, make sure to tag Florida Governor Ron DeSantis. I will put our social media shareables and more details in the show notes.

I also want to take a second to call out the Washington Post and USA Today for their quote-unquote “felon” language in their headlines about this Supreme Court story.

It is not acceptable to talk about people as only the worst moment in their lives. It is not acceptable to reduce people to only that worst moment, to totalize them as if the only thing that ever mattered about them is their criminal conviction. And it’s not okay to use a pejorative to label every single person who has a criminal conviction.

Okay, let’s get to my discussion with Tawana Petty and Alex Vitale about policing and Operation Relentless Pursuit.

Tawana Petty is a mother, social justice organizer, youth advocate, poet, and author. She’s involved in water rights organizing; data and digital privacy rights education; and racial justice and equity work. She is the director of the Data Justice Program for the Detroit Community Technology Project, and is a convening member of the Detroit Digital Justice Coalition.

Alex Vitale is a Professor of Sociology, and Coordinator of the Policing and Social Justice Project at Brooklyn College. He’s also the author of the book The End of Policing. Hello to both of you and a hearty welcome to the Decarceration Nation Podcast.

Alex Vitale:

Thanks. Glad to be here.

Tawana Petty

Thank you.

Joshua B. Hoe

I always ask the same first question, and you can go one at a time on this one. How did each of you get from where you started out in whatever work you were doing to where you’re doing the work you’re doing today around policing or problems of our criminal justice system?

Tawana Petty

I’ll start. I am a lifelong Detroiter, a social justice organizer, artist, and activist who has been intricately involved in other struggles in the city, including water shutoffs and digital access and equity work. And so throughout that work, I co-led a research project called Our Data Bodies, which was looking at the ways that community members’ digital information was collected and stored and how it would impact their livelihood – whether they were able to make a living. So if you make a small mistake in your life, and then that information is shared and integrated within data systems . . . . organizations, it would have a tremendous impact on whether you were able to move into a home, afford your water and things like that. Throughout that research, we learned that community members consistently, across three cities – we were focused in Charlotte, LA, and Detroit – they kept saying, I feel like I’m being watched. I feel like I’m being watched. I feel like everything that I do is tracked and targeted, and I’m feeling traced and monitored. And I just want to be seen [as a normal human being]. And that means more about the systems that are creating the sort of community they’re having. And so, what are these systems that are making you feel watched? And that led me to resisting surveillance, facial recognition, and mass surveillance systems in Detroit. Also, contemporaneously with that, Detroit previously had a program called Detroit One, which was participation between ATF Border Patrol, ICE and other federal agencies back in 2012. And we did a lot of writing and research and pushing back against that conglomerate, that coalition of efforts in the city. And it kind of just fell to the wayside, like they stopped talking a lot about it, and you would only really hear whether those officers were on the ground if there was an interaction that led to a violent outcome. And so when Operation Relentless Pursuit came to our door – I was actually watching the press conference when US Attorney General William Barr announced Detroit – I said, Oh, no, this is Detroit One on steroids essentially. And so yes, a continuation of the mass surveillance resistance work feels like a continuation of the Detroit One organizing.

Alex Vitale

In college I studied urban economic development; community development work; and housing stuff. I went to work at the San Francisco Coalition on Homelessness around 1990 to do that work, but it was at that time that we began to hear from folks out on the streets that there was this huge uptick in police harassment. And my boss at the time, Paul Bowden, asked me to look into this and I worked with some lawyers and outreach workers and we started talking to people and doing some research and it turned out this was the beginning of “broken windows” policing. And what I quickly figured out was that what had happened in San Francisco was that they had given up on the possibility of actually housing people and had decided instead to turn the problem over to the police, to kind of keep a lid on, to manage the problem. And this was really an eye-opening experience for me. And I basically learned that whenever we see a problem turned over to the police to manage, we should look for the kind of political failure that underlies that decision. And we can see that today, in turning social distancing over to the police to manage; turning our current political debates over to riot police to manage; but also – in a more straightforward sense – failed schools, inadequate mental health services, inadequate substance abuse treatment options, and inadequate jobs and opportunities for young people. Instead of addressing those problems, our political leaders in both parties have just turned those problems over to the police to manage. And so over time, I got drawn more and more into this work about policing because we can’t really understand the nature of urban problems and urban development without understanding the ways in which policing has been turned to as the toxic alternative to any real program for racial or economic justice.

Joshua B. Hoe

I think we have to foreground our conversation about policing and Operation Relentless Pursuit, with this kind of unfortunate fact, [that] over the last few months, and particularly over the last few weeks, there’s been a spike in violent crime, among an overall decline in crime in major cities across the country. And of course, the police are claiming that the spike is the fault of things like protesters, COVID releases from jails, and criminal justice reform. Is there anything either or both of you would like to say about this momentary increase in crime or about these official explanations?

Alex Vitale

Actually, my understanding is that overall crime rates are still down. There’s been an uptick in homicides in a handful of places, but not even as a national trend is my understanding. So what we’re seeing is the typical kind of fear-mongering that happens from the “thin blue line” supporters who think police and authoritarian interventions are the only best solution to every problem. And in New York, we just had research that came out today that showed that even though the police have been saying the uptick in homicides is because of bail reform, in fact, nobody who’s been released as a result of bail reform is implicated in any of these homicides. So this is just politically-driven rhetoric to try to dial back the power and intensity of the criminal justice system.

Joshua B. Hoe

Have you noticed anything or have you been thinking about this at all in Detroit, Tawana?

Tawana Petty

Absolutely. I mean, 40% of the deaths due to COVID-19 happened in Detroit for the entire state of Michigan. Almost 50% of the residents in the city of Detroit have lost their jobs since COVID-19. [They] had a median income of under $29,000 before COVID-19. So to me, it was foreseeable that an under-resourced city that is suffering tremendous losses – tremendous losses to death; tremendous losses to income; not having accessible and affordable water even during a pandemic – that an increase in crime might happen. The quality of life crimes are legitimate – not legitimate – but a real outcome. The defunding police conversation is so significant because so much of the budget is not going to things that could prevent quality of life crime. And so, yes, we have a high crime situation in Detroit, but we also have a very, very underserved population, who has been disinvested in for decades, and it’s going to get even drastically worse, post-COVID-19. We’re going to see mass evictions, we’re going to see mass water shutoffs again and we’re going to see people who are without a way to feed their families. And so that’s why we really have to have a discussion about how do we move money into medical, into mental health, into resourcing neighborhoods that are not resourced at this time?

Joshua B. Hoe

As Tawana mentioned, earlier in December, Attorney General William Barr introduced Operation Relentless Pursuit, and as he put it in the opening memo, he pledged to intensify federal law enforcement resources in Albuquerque, Baltimore, Cleveland, Detroit, Kansas City, Memphis, and Milwaukee – seven American cities with violent crime levels he says are several times the national average. Specifically he said “Americans deserve to live in safety. And while nationwide violent crime rates are down, many cities continue to see levels of extraordinary violence. Operation Relentless Pursuit seeks to ensure that no American city is excluded from the peace and security felt by the majority of Americans”. My understanding is that in the entire history of policing in the war on drugs, we really haven’t been very successful with enforcement of this kind reducing crime. Is that correct, Alex or Tawana?

Alex Vitale

There are some studies that show if you flood a community with police on every street corner, that there’s a little bit of a reduction in street crime, including violence. And if you go in and you arrest 100 young people from single public housing development, there will be a short-term reduction in certain types of crime in that area. That comes at a huge social cost. The effects in the reduction of crime are often quite small. You don’t get a big crime drop, you just get a small but statistically significant crime drop. And this is not a long-term strategy for building up communities, for building up individuals; it’s about putting a lid on a problem, rather than really getting to the root of it.

Joshua B. Hoe

And Tawana, you said earlier that you thought this would end up being Detroit One on steroids. Could you explain that a little bit more?

Tawana Petty

The coalition of federal agencies and law enforcement existed around 2012, which had the Detroit Police Department, US Border Patrol, US Immigration and Customs Enforcement, Homeland Security Investigations, MI Department of Corrections, and the Michigan State Police. And the US Drug Enforcement Administration – or DEA – was kind of like this pilot program that they had launched in Detroit where they were putting them out to kind of tackle gangs, as an example. So saying that Operation Relentless Pursuit is on steroids. . . . number one, it’s being ramped up across all these other cities. And number [two], it doesn’t have a central focus; it’s basically saying we’re relentlessly going to pursue these people that we consider to be criminals. And I feel like another reason why it’s on steroids is that it’s going to be coupled with – at least in Detroit – a real-time crime surveillance program that is coupled with facial recognition. And so we’re looking at potential automation of this system that is really going to have a negative impact on communities that are already over-policed, over-profiled and predictively policed. And we saw with the Robert Williams case in Detroit, what false arrest is, and so I think it’s very dangerous that Operation Relentless Pursuit exists, but also that facial recognition persists, and mass surveillance persists in the city.

Joshua B. Hoe

One of the presumptive reasons for doing this is because of drugs. My knowledge of the history of the War on Drugs, is that we’ve never, in all these years, even been able to reduce supply significantly in any of our communities. In addition, enforcement tends to make drugs more deadly, and the environment surrounding transactions more violent. Do you feel like there’s any reason to believe that Operation Relentless Pursuit would result in anything but more failures of the war on drugs?

Alex Vitale

Well, there’s certainly no reason to think this would do anything positive on the drug front. We just have an ocean of evidence that shows that all this enforcement does not work. We can look at things like Operation Flytrap, which was a major, one of these multi-agency task forces, and all it did was criminalize low-level drug users, no one went five minutes without access to drugs. I mean, that’s so central here, that when you look closely at these operations, they can’t possibly work, because you just see that there is this incredible, widespread decentralized system for drug distribution, a massive level of demand, and interdiction efforts like this just don’t work. It’s time to get police out of the drug business, where there is incredible abuse and corruption, and turn this over to public health authorities; get systems of decriminalization and legalization; harm reduction and treatment [programs]; as well as targeted economic development programs to deal with all the folks who turned to drugs out of their economic necessity or hopelessness and trauma, and really have a complete rethink. And the idea that flooding these cities with more police and more arrests is going to do anything about the drug problem is just ridiculous.

Joshua B. Hoe

Tawana, how have you seen the on-the-ground effects of the continuing drug war in Detroit?

Tawana Petty

I’ve basically seen the effects of continued disinvestment in Detroit. Devices that are available to community members to take care of their families are the devices that folks are going to use. Like I said, in our major metropolitan city, the median income pre-COVID-19 was only $29,000 a year. We have 50,000 kids in this city. Most of them are living in extreme poverty; don’t have access to the internet; water may or may not be on in their home; the schools are not being invested in in the way that they need to be invested in. And so, you know, I touch and agree with Alex. I’m also thinking about this new notification I read about where [kids] have meth in their house, it looks like candy, it looks like vitamins and candy. And so what’s the solution when young people get access to this? Are we going to lock up every kid that becomes accidentally addicted to drugs? I think the type of . . . . inner cities is the same type of imagination that you see in suburban communities, where the demographics are not predominantly black or brown. And so basically it feels really strange to always have to have a conversation where we’re begging for our humanity, or we’re begging folks to look at how other communities are treated when there is a drug problem, or where there’s a problem with any degree of criminality. You know, there’s investment that comes into those communities; there are resources that come into those communities. But when it comes to a city like Detroit, [which is 80% black], it seems the thing is to massively surveil, predictively police, and criminalize. And so I think that we have enough evidence to show that that is not the way that you get people to function in their most humane . . . to function at the highest . . . to reduce crime.

Joshua B. Hoe

It seems like there are two other elements that they’ve talked about in Operation Relentless Pursuit, one of which is a crackdown on gangs. Do either you want to talk about this notion of federal support, local support, and the kind of ganging up against gangs, so to speak?

Alex Vitale

This is another incredibly misguided strategy, something that the Policing and Social Justice Project that I coordinate has been working a lot on in New York. We recently issued a report which you can see on our website, www.policingandjustice.org, that shows that New York City, over the last six years or so, has been classifying more and more activity as gang-related in black and brown communities, and then has ramped up gang suppression policing, using broad-ranging conspiracy cases; creating gang databases; doubling, tripling the size of the gang unit; getting . . . . police to put kids on the gang database. And the research shows that this actually just hardens gang identities; it takes loose affiliations of young people and social networks [and] hardens them into real gangs that see themselves at war with the police and at war with those who criminalize them. We’ve called instead for the use of community-based anti-violence initiatives, social-inclusion strategies to bring people, young people, into mainstream society in meaningful ways. Provide young people with real pathways to self-sufficiency, to deal with the long history of trauma. All these young people who get involved in violence have almost all been the victims of violence [themselves] and that victimization has never been addressed in any meaningful way. So this is really about breaking the cycle of violence, giving kids who’ve turned to the streets better options. And when we criminalize them, we drive them into a criminal justice system where gangs are the norm, violence is the norm. Then when they come out and commit additional acts of violence, we’re like, oh, my god, they’re hardened criminals; they’re [not] rehabilitatable. We made them into this! And so we need to break that cycle of criminalization as well.

Joshua B. Hoe

We’re obviously in the middle of what has become a long-overdue national discussion about policing in general. The third element of Operation Relentless Pursuit seems to be to increase police on the street. Do you all want to talk about that?

Tawana Petty

I just want to drive home for folks the difference in how communities are treated. A perfect example is that we’ve seen an inordinate amount of school shootings in white communities and [those] have been very tragic, tragic situations where young lives are lost. What we did not see was city governments or law enforcement flood the street in white communities, or white schools with metal detectors and police officers and this militarized, general criminalization of those school systems. And in black communities, even in schools that are high-performing, that have kids with a 3.8, 4.9 GPA, they have to walk through metal detectors. They’re literally criminalized from the minute they enter school until the minute they exit the school. And so that is a kind of social conditioning that is happening in the school system that is telling these kids that they are predisposed to crime. And so in some communities, some children escape from that type of social experiment and a lot don’t, especially if they’re then going to homes that don’t have water, don’t have access to resources, and those sorts of things. And so to touch on what you previously talked about, and talking about the flooding of neighborhoods with law enforcement, we understand the things that make us safe. We know that safe neighborhoods tend to be resourced neighborhoods, safe neighborhoods tend to be neighborhoods where there are viable grocery stores where community members can buy foods that are not expired. If you look at Detroit as an example, there are a lot of neighborhoods that don’t even have a grocery store …. that liquor stores, and a lot of times that food is not really edible. And you’re looking at [neighborhoods] that don’t have a school; the children don’t even have a school where they can walk to, and those sorts of things. And so yeah, the flooding of police in neighborhoods to respond to criminal activity versus the flooding of resources to prevent crime is just a backward way of thinking.

Joshua B. Hoe

We live in a society that has an unprecedented system of mass incarceration, huge numbers of police and prosecutors. And most of it was built on the back of public fears about safety. The tenor of most of these initiatives, from the Department of Justice under this administration, has seemed to start from this same position of fanning fear. So how do we start changing this narrative and getting people to see beyond their fears?

Alex Vitale

I think it’s important that we think about Operation Relentless Pursuit as a political project by the Trump administration. They’re trying to say to the American people that the problems of Detroit, Cleveland, Memphis, Milwaukee, Baltimore, etc, that the problems of those cities are about criminals running wild in the streets; about a kind of moral failure in certain communities; and that the appropriate response is criminalization. And this absolves them of any responsibility for the failure to have an economic policy for cities; to invest in infrastructure; to improve education; to create real employment opportunities; to provide adequate health care for people. So it’s like I said at the beginning . . . instead of dealing with real political problems, they’ve turned it over to the police. And that’s really what’s going on here. And the question I have is: why do all seven of the cities that have been targeted have Democratic mayors? And what I want to know is why are those Democratic mayors going along with Trump’s tough-on-crime reelection strategy, a strategy that is based on this idea that he doesn’t have to do anything to help these cities except provide them with more cops?

Joshua B. Hoe

Even in cities like Detroit – you know, I live in Ypsilanti, so not very far away – where people have a healthy skepticism for policing, we’ve still seen things like Project Greenlight cover nearly the entire city in surveillance. Is this a failure of organizing, activism, education? What are we doing right? And what do we need to do differently Tawana?

Tawana Petty

One thing that I’m always cognizant of in Detroit is that you’re looking at a city that has suffered essentially under a half-century, targeted . . . . . assault. So my entire life – I’m 43 – my entire life, Detroit has had one dominant negative narrative; we’re hopeless, helpless, a criminal community of black people who didn’t want to do right and didn’t care about their city. Once you have inundated community members with that narrative, you’ve inundated children with that, and you’ve told the whole globe that this is a city that needs to be watched, that needs to be tracked, that needs to be surveilled, that needs to be policed, it becomes easier to push these sorts of policies in Detroit. And every night on the nightly news – and during the day – senior citizens who are home, who are retired, are inundated with images of crime. They’re not told the stories of viability or about thriving communities. And this makes them an easy target for things like Greenlight. Law enforcement do a lot of targeting of senior citizens to get them to buy into Project Greenlight as a means of safety. So this conflation between surveillance and safety has been something that we’ve been doing a lot of work to push back against because it does not create safety. And when I have dialogue with a lot of elders and I ask them about a time that they felt safe, none of them talk about law enforcement. None of them talk about surveillance. They talk about community black clubs. They talk about times when they knew all of their neighbors. They talk about times in history when calling the police was not the first line of defense. And so our organizing strategy has been to kind of get people back . . . . . where we’re inviting community members back to the front porches, back to look out for one another, in order to be a part of the prevention of crime, instead of using law enforcement as the first line of defense, when they’re [the police] not going to prevent crime, they’re going to react and respond to crime; and not defaulting to surveillance cameras, as a way of capturing people. And one more thing I’ll say is that I try to remind people that every person in the State of Michigan who’s taken a state ID of any sort through the Secretary of State has been fed into a facial recognition database since 1999. So essentially, everyone who comes through the city of Detroit is under a virtual lineup, until there is an exoneration by an algorithm and you better hope that the algorithm doesn’t falsely accuse you of a crime, because most times, you won’t even know that that’s why you were picked up in the first place. Law enforcement slipped up in telling Robert Williams that the computer was the one that picked him up; I can guarantee they’re not making that mistake again.

Alex Vitale

If I can just maybe add a little bit to that . . . I think part of the problem we have here is that for the last 40-50 years . . . . . they can have to fix their community problems is more police. And so, of course, when communities are confronted with real challenges, real problems, real danger – if the only thing that’s available is more police, they’ll ask for more police. And what this movement to reallocate resources, to rethink policing is calling for, is that we provide real things to communities that will make them safer, and not limit the conversation to how many police we’re going to have. And it’s the challenge of this movement – doing that community organizing with our neighbors to convince them that we have better alternatives to produce public safety than just relying on more police.

Joshua B. Hoe

One of my really big frustrations as this debate all started was that when people in the streets were calling for defunding the police, the media’s immediate response in a lot of ways was to let other people define what that meant, oftentimes even letting the police define what that meant. So one thing I’ve really been trying to do is let people speak for themselves. Could each of you talk a little bit about what you think the start of a solution means to you?

Tawana Petty

And I’ll go first because I know Alex has . . . . . worth of analysis around this that I totally agree with. But I’d say as an example, divesting from mass surveillance in the city would be tremendous. There’s been $30 million spent on just the real-time crime surveillance program, which has not [improved] safety. In addition if you’re looking at the police budget, which is at least $300 million – that doesn’t include other grants and things that are not with that figure – and you look at the health budget, which is like $9 million. So divesting from the militarization of policing, the mass surveillance of policing; and adding funds into mental health, adding funds into affordable portable water programs, adding funds into educational programs, and healthy foods in communities, and . . . . . they’ll be done almost immediately. And I don’t think that we’re in a position anymore to beat around the bush about this. We need to get rid of facial recognition immediately. And we need to pull back on the surveillance of these communities and make sure that residents are able to take care of themselves.

Alex Vitale

This is a public safety movement led by people who have experienced harm and violence in their communities, and they want to create safer communities than the system provides them with now. And they understand that these have often not been a real source of safety and security for them. And so what I often recommend is that what we need to do is go talk to specific individual communities about the specific public safety challenges that they face. And then work with them to articulate what the alternatives might look like. We’ve got to look at the examples around the US and around the world. And we also have to experiment. We have to come up with new strategies, we have to evaluate them, and we have to build on that knowledge. It’s going to include things like getting police out of the mental health business and creating real community-based mental health services. It’s going to be about creating community-based anti-violence centers that can deal with domestic violence and youth violence in more definitive and productive ways that lift people up, that restore individuals and communities. It’s going to look like replacing school police with more counselors, better after-school programs, restorative justice initiatives. It’s gonna look like police are out of the sex work and drug business, providing real social services for people, harm reduction initiatives, etc. So there’s a lot of options out there. And we’ve got to start with these assessments and also some clear-headed thinking about how reforming the police is not the solution. It’s replacing the police with credible alternatives.1

Joshua B. Hoe

Now, I’ve noticed – I’ve done a lot of following of the debate or the pushback against some of your suggestions – and much of the pushback, in my opinion, seems to be based in studies which you referred to a little earlier, which find that police presence – time, place and manner kind of presence – has at times deterred violent crimes. At the same time, there’s a decent amount of evidence that suggests that the police don’t prevent a lot of crimes and that they certainly don’t solve at least a lot of the serious crimes. Do you have any kind of response to the pushback that police in certain moments in time – like, as you said, if you flood them in areas – have an effect on deterring violent crime?3

Alex Vitale

So, you know, the long term trajectory of this research, going back decades, is actually very pessimistic. It does not show effectiveness for policing; the number of police, [or] how police are deployed, doesn’t make any difference to crime rates. Now, recently, a few economists have crunched some numbers, looked at a couple of isolated examples where they find some very small effects where you can get a very small reduction in certain types of crimes with very big police interventions. Those studies never calculate what the costs of those interventions are. Just assume that policing is this completely positive or neutral intervention without thinking about A, the material cost, how much of the budget goes into it, and how that money could be spent in other ways – a kind of question of opportunity costs – but also cost to a community of all that intensive policing. Know, for instance, that for African-American men, the intensity of their interaction with police actually has negative measurable health outcomes for them because of the level of stress and social dislocation that goes with that. It also contributes to profound racial inequalities in American society because it treats certain communities in this punitive way while other communities get a pass; their problems get addressed in other ways. So even if we can show some small level of effectiveness in the short term, you have to keep in mind it comes with tremendous costs, and it’s not the only possible strategy. Policing should always be understood as a harmful strategy that should be used as an absolute last resort, after we’ve exhausted all other less punitive, less violent possibilities.1

Joshua B. Hoe

Yeah, I find it interesting that a lot of the opponents seem to cling to this Patrick Sharkey quote about how police can be effective, but [they] ignore the rest of his article, which is essentially about the opportunity costs of investing only in that solution. Is it fair to say that police don’t actually solve much violent crime?3

Alex Vitale

Oh right, you mentioned that; so [yes] that’s definitely true. I mean, the stuff that Sharkey points to, and really he’s bending over backward to seem reasonable and he wants to work with police, right? And he feels like if you don’t say police are part of the solution, [then] the police will cancel you and they’ll never talk to you again. So, there’s a lot of this bending over backward. They’re interested in policing as a proactive intervention, because policing as a reactive intervention, no one thinks that works. Most crimes are never even reported to the police. Most low-level property crimes that are reported are never investigated. Estimates from the Vera Institute suggest that only about 10% of serious crimes get quote “solved” by the police. And clearance rates even for things like rape and homicide are often less than 50% of those crimes that are reported. And so this idea – that [like in] CSI and Law and Order, and all these TV shows – the police are gonna come and solve the crime, and that’s going to make the community safer – that’s just clearly not true.1

Joshua B. Hoe

What’s been your experience with these kinds of questions in Detroit, Tawana?2

Tawana Petty

I mean, I would agree. I agree with what Alex is saying. And I think we also have to think about the economics of some of these systems that are going to prevent people from wanting to use their imagination. If I just look at the fact that Detroit is being leveraged as a model across the [country for] our real-time crime surveillance and facial recognition program, then there’s a lot to lose, if they lose this battle and we win a ban. And also globally, the facial recognition market is projected to reach over $12 billion by 2020. In addition to showing that police do not prevent crime, that they’re unable to solve a lot of the violent crimes that do happen, they are tied to convincing the public that this new technology is going to do that solving for them. And then, wanting to be able to package this up and roll it out. And it makes a lot of money for the city and so there’s an economic benefit to rolling over the solution, the quote-unquote “solution”, to unsolved crimes into automated algorithmic technology.

Joshua B. Hoe

This is the Decarceration Nation podcast, and this season I’ve been asking my guests if they have any ideas that would be helpful for decarcerating our country. Not to put you on the spot, but if you have any thoughts here, I’d love to hear them.3

Alex Vitale

One of the big motivations for writing my book, The End of Policing was that I felt that so much of the country’s conversation about the criminal justice system was focused on mass incarceration, and very little attention was being paid to the role of policing. The reality is, that nobody gets into prison without first getting arrested by the police. So we can interrupt the process at that level, at that stage. That’s the best possible strategy because there’s all this discourse about reentry and recidivism: we’ve got to invest in people who come out so they don’t go back in and I hear that; I feel for people who are caught in this system. But the reality is that a lot of damage has been done already. Most of these reentry programs don’t show great success. Recidivism rates remain very high. Even people who don’t recidivate have very tough lives ahead of them because of all the negative stigma that’s been placed on them. If we want to reduce mass incarceration, we’ve got to engage in widespread de-policing and decriminalization; we’ve got to end the war on drugs; and we’ve got to come up with alternatives to addressing patterns and cycles of violence. We’ve got to quit all this low-level broken windows enforcement that constantly cycles people through the criminal justice system.

Joshua B. Hoe

Did you have thoughts too Tawana?

Tawana Petty

Yeah, and I’ll also say the ending of policing doesn’t just stop with law enforcement. It stops with the mentality that some folks have internalized, like the social work system, the public benefits system. There are folks who are acting as kind of an extension of policing in the ways that they respond to community members. We have folks in schools who are calling the police as the first line of defense for even kindergarteners. And so I think that there has to be a massive re-education of folks, and thinking about policing systemically, and not just individual officers and the ways that our systems have been conditioned to be an extension of law enforcement.

Joshua B. Hoe

I always ask the same last question. What did I mess up? What questions should I have asked but did not?

Alex Vitale

I think you’ve covered a lot of territory today. And I think we need to focus on these big-city mayors, who continue to turn every social problem over to the police to manage, and then try to paper it over with a bunch of superficial reforms, and aren’t really going to get to the problem.

Joshua B. Hoe

Well, I want to thank you both so much for doing this. It’s really been great to talk to you and I hope to run into you in person sometime soon.45:10

Alex Vitale

That would be great. I was in Ypsilanti a couple of years ago. I’m sorry we didn’t get to meet up then.

Joshua B. Hoe

Oh, that is too bad. I’m sure at some point, we’ll cross paths. Tawana it is very nice to meet you too.

Tawana Petty

You as well.

Joshua B. Hoe

And now my take.

I’m very concerned that there are stories over the last several days of de-identified federal law enforcement officers arresting people in Portland. Some people have suggested that these forces are only arresting people who are suspected of damaging federal property. Okay. Let’s pretend that’s not problematic. But why in the world are they de-identified? Why are they not working in cooperation with local law enforcement? And how in the world are they identifying suspects in the streets, as they seem to be making arrests during these protests? There are reasons local communities insist that law enforcement officers have names, have a unit insignia, and have a badge number. Police serve the people and when abuse happens, the only way the public has to identify guilty parties is through police transparency. These federal forces have no names, no units, no insignias, and are wearing what appear to be military uniforms and masks. What possible justification is there for having anonymous forces, arresting people supposedly, in a democratic country? I’m also really troubled by how these rogue federal law enforcement shock troops are identifying suspects in the street. I can only imagine that facial recognition algorithms and surveillance are involved. And this should also be deeply problematic to people who care about liberty and people who just listened to our discussion with Alex and Tawana. I say they are rogue because they are not identified. They seem paramilitary and could actually be military. And they make no attempt to be accountable or transparent. This is how fascist states operate. This is the second time where we have seen this administration and the Department of Justice send de-identified law enforcement into protests, and it is not okay. We are supposed to be a nation of laws. And we give power to the police, prosecutors, and judges to enforce those laws. But that grant of power is conditioned on enforcement being done in a legal and transparent manner. Our Bill of Rights is designed to ensure that there are limits to the power of government, and that the government is accountable to the people. De-identified troops are not accountable to anyone. It may turn out this was a limited incursion, but this is still not okay. This is lawless law at its most foul, and at its least democratic.

As always, you can find the show notes and/or leave us a comment at DecarcerationNation.com.

If you want to support the podcast directly, you can do so at patreon.com/decarcerationnation; all proceeds will go to sponsoring our volunteers and supporting the podcast directly. For those of you who prefer to make one-time donation, you can now go to our website and make a one-time donation there. You can also support us in non-monetary ways by leaving a five-star review on iTunes or by liking us on Stitcher or Spotify.

Special thanks to Andrew Stein who does the podcast editing and post-production for me, and to Kate Summers, who’s still running our website, and helping with our Instagram and Facebook pages. Make sure to follow us on Twitter, Instagram and Facebook, and share our posts across your networks. Also, thanks to my employer, Safe and Just Michigan, for helping to support the Decarceration Nation podcast.

Thanks so much for listening; see you next time!

Decarceration Nation is a podcast about radically re-imagining America’s criminal justice system. If you enjoy the podcast we hope you will subscribe and leave a rating or review on iTunes. We will try to answer all honest questions or comments that are left on this site. We hope fans will help support Decarceration Nation by supporting us from Patreon.

1 thought on “85 Tawana Petty and Alex Vitale”