Joshua B. Hoe talks to reporter Radley Balko about policing and accountability

Full Episode

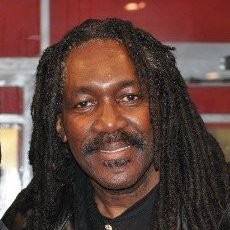

My Guest – Radley Balko

Radley Balko has been a journalist for 20 years. He has worked at the Washington Post, Huffington Post, and Reason magazine, he has also written two widely-acclaimed books, Rise of the Warrior Cop and The Cadaver King and the Country Dentist which was co-written with Tucker Carrington.

Watch the Interview with Radley Balko on our YouTube Channel

You can watch Episode 143 on our YouTube channel

Notes from Episode 143 Radley Balko – Police Accountability

The book Radley Balko recommended was Smoke and Mirrors by Dan Baum and Roger Donald

Mr. Balko’s substack is called The Watch

Full Transcript

Joshua Hoe

Hello and welcome to Episode 143 of the Decarceration Nation podcast, a podcast about radically reimagining America’s criminal justice system.

I’m Josh Hoe, and among other things, I’m formerly incarcerated; a freelance writer; a criminal justice reform advocate; a policy analyst; and the author of the book Writing Your Own Best Story: Addiction and Living Hope.

Today’s episode is my interview with Radley Balko about police accountability. Radley Balko has been a journalist for 20 years. He’s worked at The Washington Post, The Huffington Post, and Reason Magazine and has also written two widely acclaimed books: Rise of the Warrior Cop, and the Cadaver King and the Country Dentist, which was co-written with Tucker Carrington. Welcome to the DecarcerationNation podcast, Radley Balko.

Radley Balko

Thanks for having me on. It’s good to be here.

Josh Hoe

I always ask the same first question. How did you get from wherever you started in life to where you became a journalist and author specializing in police and police accountability?

Radley Balko

Ah, sure. So I kind of always knew I wanted to be a writer in some form from an early age and it was just kind of a matter of getting to where I could make a living doing that. So at one point in my 20s, when I was kind of figuring out what to do, I did what lots of people do, which is went to law school, I went there for a year and decided, looking at the debt, that I would have probably have to work for a firm for about 20 years if I continued on. So dropped out, took a job with a dotcom doing writing, sort of entertainment writing, in the late 90s. they promptly went bankrupt, like most dot coms did and I ended up with the Cato Institute, the libertarian think tank in DC. I was editing the website there for a while. And then eventually I got a policy job covering civil liberties. And it was really there that I think I really started taking an interest in these issues. I grew up in a pretty conservative, pretty much all-white town in Indiana in the suburbs of Indianapolis. And, you know, I kind of figured out at some point in my 20s, that I was a libertarian, early 20s, I guess. But it was really at Cato in covering civil liberties and the drug war that I you know, I think, probably found kind of my calling or the issues that I wanted to sort of cover or I was most passionate about, it was really just reading these stories about swat raids, and, you know, abuse of informants and killings related to the drug war. You know, I’d read about these stories and it would just make me angry. And they’re the kind of stories that I was fascinated by, but also infuriated by and decided that you know, at some point that this is kind of what I wanted to cover full time or kind of dedicate my work to. I ended up going to Reason Magazine because I was writing a white paper for Cato on the use of SWAT tactics and forced entry raids and found the story in Mississippi about this guy named Cory Maye, who had been wrongly raided by a narcotics unit in Mississippi. He lived in a duplex, they were clearly trying to raid the guy on the other side of the duplex, who was their suspect. Corey [who] had no prior criminal record, shot and killed one of the cops during the raid and then immediately surrendered after he realized they were police. When I found this story, he was still on death row in Mississippi. So I started looking into that case, and I blogged about it at the time, this was in the early blogging days, and ended up writing an article about it for Reason Magazine. Reason hired me and kind of put me on this beat full-time. And that’s kind of where I am now. I ended up going to Huffington Post and then the Washington Post for about 10 years. And now I’m independent, and you know, operate on my [own], well I’m doing a lot of freelance work, but also write on a Substack, which is just me radleybalko.substack.com. It’s called the watch. And you know, it’s kind of my beat; I do long-form investigative stuff, but also analysis and commentary on criminal justice, the drug war, and civil liberties issues.

Josh Hoe

I know I started to get to know you because of your Twitter feed. But since then, I’ve caught up with your Substack and a lot of your other writing. But briefly, since we’re both kind of longtime Twitter users, what are your thoughts [about] the current state of Twitter – before we move into more topical stuff?

Radley Balko

Oh, it’s awful. I mean, I think Musk has driven it into the ground. He’s amplified – I’ve sort of compared what he did what he’s done to Twitter to, you know, at a football game, finding the drunkest and rowdiest section of fans and giving them the intercom system you know, they want to win Have it because he’s really amplifying the worst voices? And, yeah, it’s, it’s, it’s bad, you know, I still use it because, you know, I’ve spent 15 years building a following, and I make my living basically from people, you know, following and subscribing to my work. So it’s hard to kind of walk away from that. But yeah, I totally feel you on that. I’m really hoping, you know, Blue Sky, it’s there’s probably going to be Blue Sky, but any of them, you know, gets a, once it goes public, you know, and is widely used, opens it up to the public, I’m hoping they’ll get that critical mass of users that I think you need to make it useful.

Josh Hoe

So a few years ago, we saw the start of a crime wave that generated a number of political narratives and a lot of reactions, a lot of attention on progressive prosecutors, a backlash against both police reform and against police reform, backlash against the reform of the rest of the criminal justice system. There are several parts of what caused this first, there’s gun violence and homicides. Do you have any feeling for what we’ve had for a couple of years now? Do you have any feel for what’s caused these increases? I mean, my running theory has been that COVID might have something to do with it. But where are you on this?

Radley Balko

Yeah, I think there are probably a variety of contributors. I think that anybody who claims to know definitively what caused it is probably somebody you shouldn’t listen to. You can’t help but notice that it coincided with a once-in-a-century pandemic, which upended every part of our lives. And, you know, historically, when there have been rises or steep increases in homicide, it’s come during times of social upheaval and unrest. And you know, a lot of people having to change their lives, a lot of people becoming sort of aware of and angry at the way they and people like them are treated by the political system, by the criminal justice system. You know, I think it’s kind of a mistake to say the George Floyd protests had nothing to do with the increase in crime. I think, you know, there’s plenty of research showing that when people become disillusioned with the criminal justice system when they think that the police are there to harm them instead of help them, they stop cooperating with police, and crime goes up. And you know, I think one thing George Floyd protests did, and I think they did a lot of good and I’m not even sure this is a net bad, but they did kind of make more people aware of the flaws in policing and the flaws in the criminal justice system and the inherent racial inequities in both. But that said, I think COVID is probably a better, or a better explanation for a greater percentage of the increase. You know, you’ve had everything from general kind of social upheaval, COVID also sort of focused people’s attention on inequities in the healthcare system. And boy, you know, we treat certain people, the way we treat marginalized groups. You also had disruptions in drugs, in the black market, you know, the drug markets. So you had, you know, probably less people using, you had less police, you had probably disruptions in supply. So anytime that happens, you’re gonna have people fighting over turf. And of course, because drugs are illegal, you don’t win over new customers with better customer service or better products, right, you win it with violence. And then the other thing that I think is a little bit overlooked, and I wrote a column on this for The Washington Post, but you know, it’s probably less true now, although we are seeing homicide numbers start to decline all over the country at this point, but certainly for…

Josh Hoe

For the first time, and it’s one of the largest declines in a really long time, historically.

Radley Balko

Right? Well, that’s also I think, because we had this artificial blip, you know, artificial increase that now is coming back down. But, you know, I think one overlooked factor is that in the first couple of years of the pandemic, we had fewer witnesses, right, people were staying home, people weren’t going to work, they weren’t going to bars and restaurants, they weren’t out late at night, you know, after coming home from a bar, which tends to be when a lot of crime happens. And studies have shown over and over again, that when you have fewer people watching, people tend to commit more crimes. And so right at the same time that these, the black markets for illicit drugs are being disrupted, and you’re having these fights over turf wars and fighting over this kind of change in the customer base, you have fewer witnesses on the street. And so it becomes easier, you know, to harm people and to kill people, because there’s nobody around to watch and I think that that might be one overlooked contributor to the increase, at least in homicides.

Josh Hoe

Then there’s the other end of the crime spectrum, which is that there’s been a wave of retail thefts, or at least reported a wave by retail shops. Do you have a feel for what was accurate and inaccurate? And what might cause that kind of crime-increase?

Radley Balko

Yeah, that’s, you know, that’s tough. Because we saw an increase in homicides, almost everywhere in the country, the retail theft thing is, you know, it’s hard to get a sense of what’s actually going on there, it’s hard to get a sense of if there really was a significant increase. The Atlantic had a good nuanced piece on this a couple of years ago, but they tried to look at the numbers. You know, even in places like San Francisco, where you saw most of the hysteria, the moral panic, over shoplifting. The numbers really didn’t bear that out. Now, the response from the law and order crowd as well, why would you report shoplifting if it’s not going to be prosecuted if people aren’t going to be arrested? And the problem of that is, I actually looked into this a little bit – and, you know, retailers have lots of incentives to report shoplifting. In fact, most shoplifters, even before the pandemic before all of this happened, aren’t caught. And they’re even less likely to be caught now, because, you know, retailers, like Walgreens and CVS, have told their security people, their security guards, to stop detaining people suspected of shoplifting basically for liability reasons. So people are more likely to get away, but the idea that it’s not being reported just doesn’t make a whole lot of sense. If I’m a manager with CVS, I have to explain to my regional regional manager or the corporate people the explanation for shrinkage. And so, you know, it’s in my interest to report shoplifting, and it’s in the corporation’s general interests, because one, for insurance purposes, so they get reimbursed for stolen merchandise, but also, because it makes sense for them politically, right? They want laws to crack down on shoplifting, they want more public and political attention on shoplifting. So, you know, it’s in their interest to make shoplifting look as bad as possible. So, you know, I just don’t buy this idea that there’s an incentive for them or disincentive for them to report it. So if that’s the case, you know, the numbers don’t bear out the idea that there’s been this mass wave, I think it’s gone up a little bit in the last couple of years. But when the hysteria over it started, the numbers suggest that it’s been going down, but I’ve seen other increases and other types of crime, break-ins in places like San Francisco, we’ve seen a lot of cities, I’ve seen really significant increases in car theft and carjackings. And, you know, I mean, there are lots of possible explanations, I’m not going to claim to know, to definitively say, This is what caused it, but during the epidemic, you had a lot of teenagers at home with nothing to do, everything was closed, they weren’t going to school. You know, kids, it’s…

Josh Hoe

It’s kind of similar to the explanation for why there was a spike in domestic violence [that] people are home so much.

Radley Balko

Exactly. Kids get bored, and they do stupid shit, I did stupid shit when I was a teenager. I didn’t steal cars. But I did some vandalism. You know, I put firecrackers in mailboxes. So, I think that’s a pretty good explanation.

Josh Hoe

So, you know, I don’t want to spend too much time talking about the other explanations that don’t make a lot of sense, like, you know, despite the fact that it was a fairly universal increase, that certain types of policies caused it or certain kinds of promises.

Radley Balko

Lots of academics have looked into that. People from John Pfaff, you know, who does have a perspective, but people like Jeff Asher, who’s a straight numbers guy, and, you know, doesn’t really project any sort of politics, [who] as you know, has found no correlation between party affiliation or reform policies and increases or decreases in crime. There’s just no evidence of that, you know, either way. And, you know, my hunch is that policy plays a very, very small role in our crime rates. I think they’re much more controlled by these broader societal issues that vary from city to city. I mean, obviously, crime has been worse in some places than others, but the idea that criminals factor in, you know, the politics of their local DA before they commit crimes, there’s no evidence for that,

Josh Hoe

Or, you know, small changes in sentencing policy or, you know, that deterrence works that way, is a little bit hard to accept,

Josh Hoe

There’s also a persistent narrative that was about police being defunded all over the country after the Floyd murder. I was in fact, just the other night I was watching the Chris Christie Town Hall, and he suggested that police and police abilities have been degraded for years.

Radley Balko

Yeah, again, there’s no, there’s no evidence that there’s been any. I mean, I think a few cities may have diverted like 5%, maybe most 10, from policing to other sort of public safety programs like violence interruption or mental health, or you know, homelessness. But in the vast majority of the country, including places that set records for homicides, like Mobile, Alabama, Indianapolis, Toledo, you know, there were increases in funding for police and in some places, pretty significant increases. You know, I will say, I think, I’ve long been skeptical of the Ferguson Effect, and this idea that police, when they’re heavily criticized, and whenever [folks] protest and there’s a lot of scrutiny, that they sort of stop doing their jobs and stop doing . . . I guess the theory is they stop doing proactive policing, and that’s why crime goes up. I don’t think there’s much evidence for that. I do think there’s some evidence that they just kind of stopped doing anything. And, you know, the evidence for that is what police organizations themselves have said, right? I mean, the Chicago police union head said, if the more progressive candidate wins the mayoral election, the cops have stopped doing their jobs; we had the NYPD do a couple of shutdowns, or whatever they call them, blue outs. And, you know, in both cases, crime went down during those phases. But we have seen a lot of police leave departments, there’s a crisis of personnel, particularly in big city departments around the country. And, you know, I do think that people who advocate for reform, kind of have to reckon with this, this idea, but I actually think it’s people on the right, who really need to reckon with it, and this is this notion that the policing has become so psychologically isolated from the rest of society that, I think there’s, there’s some truth to the idea that when cops are heavily criticized, or when you know, there’s a video that goes viral or or now that we’re seeing more prosecutors willing to press charges against police when they kill someone, unjustly, or, or beat someone, that they do stop doing their jobs, or in some cases, they just stopped doing their jobs, because they don’t like the new leadership in the police department, or they don’t want to, you know . . . I’m working on a story about a town in Minnesota, where the town hired a black police chief, and about 80% of the police department, all white officers, quit, because they didn’t want to work for a black chief. Now, they’ll say it was some other policy like, you know, some sort of DEI initiative or something. But he hadn’t even implemented any policies yet, and they quit. You know, I do think we need to reckon with the fact that the policing profession has gotten to the point where they don’t respect civilian leadership when they don’t agree with it, and they don’t see their job as to enact the policies of the political leadership, they see their job as basically kind of to do what they want. And that’s bad for society. I mean, we’re at…

Josh Hoe

Is the far end of that what we’re seeing with the kind of sheriff’s gangs in California and stuff like that?

Radley Balko

I mean, that’s been going on forever, you know, that’s been going on for decades. No, I think what we’re seeing now is this kind of, I think it’s more we’re seeing it with a lot of these rural sheriffs who are saying they’re not going to enforce certain laws at all, they’ve become part of the kind of MAGA Patriot militia movement. But also just this idea that, like…

Josh Hoe

The so-called constitutional sheriffs, right?

Radley Balko

Right. But I also think this is on par with what police unions have been doing. And, you know, the interesting thing is, the Ferguson Effect, people on the right, the people who push this, it’s always surprised me that they pushed it, because it’s a really unflattering explanation when it comes, if you’re a defender of law enforcement, this idea that they’re going to let violence happen, they’re going to let people die and be murdered because they don’t want to be scrutinized, they don’t want to be criticized. That is not a flattering profile of the state of law enforcement in this country. But it’s increasingly looking like it might be somewhat accurate. And, you know, I think we have to kind of reckon with that. And we have to say, you know, what does this mean for policing, and frankly, you know, maybe we don’t want those people in policing anyway, right? If you’re going to resign because you don’t want to work for a black police chief, maybe you’re not the kind of person that should be holding a badge and a gun in the first place.

Josh Hoe

You know, I have had, unfortunately, some firsthand experience with both the police and correctional officers. And, the thing that they get the most wrong when you have these discussions is, at least in my experience, in that several prisons and some jails and some going from place to place and getting arrested and all that stuff, which I admit is anecdotal, but it was in every single one of those places that I went, it seemed very clear that it was very well known in those departments and in those places, and in those administrations, that there were a certain number of people in the department, who were, you know, for lack of a better term kind of “off the tether”, would be willing to do pretty much anything. And they use those people strategically. It wasn’t that there were good apples and bad apples, it was that there were good apples and bad apples and the administration knew that and used that strategically. It wasn’t that you could just excise one or whatever. It seemed to me, it was more systemic.

Radley Balko

Look, the whole bad apple thing. You know, people forget the second part of that saying, it’s like a few bad apples spoil a bunch. And if you don’t take them out, then you get more bad apples, and it becomes, you know, like a disease. And so, yeah, I mean, I say this arguing about what percentage of cops are bad or abusive or corrupt kind of misses the point. I mean, if you have a system that refuses to hold the bad, abusive, corrupt cops accountable, when it’s pretty clear that they did something wrong, you have a systemically, you know, a foundationally, corrupt system. And it doesn’t really matter, you know, this debate about like, most cops are good people, or most cops are bad people. If they’re good cops, why don’t they, you know, report the bad cops or why do they cover up for the bad cops? I mean, fundamentally, if you have a system that doesn’t hold clear, bad actors accountable, you’ve got a broken system. And you know, that’s what we have. I mean, I think there’s very, very strong evidence across the board. I mean, city after city after city, we find that a very tiny percentage of civilian complaints against police are upheld, and of those a very tiny percentage of police officers are actually disciplined in any way. And of those, even a smaller percentage are disciplined in any significant way. And even those, there’s always some sort of appeals process or arbitration, you know, that makes it extremely difficult for those cops to actually be fired. And even then, they can just get a job somewhere else. So we have a system that doesn’t get rid of the bad apples. And that’s, you know, why I think we’re seeing, not only that, but I mean – The Marshall Project and some other groups have done some reporting on this, that bad apples are usually the ones that are picked to become field training officers to train new officers, right, because they want the guys who have been around for a long time, who were sort of trusted by other cops in, in the department to show the new guys the ropes. And so they teach the worst habits, they find the worst cops with the worst habits, and those are the guys who teach the new generation.

Josh Hoe

I think that was a big part of that last David Simon piece on HBO, I forget what it’s called. But it was about kind of another thing about corrupt cops in Baltimore.

Radley Balko

We Own This City.

Josh Hoe

Yeah, that was it. We Own the City. Here, and when we start talking about this, the thing that eats away at me and is crazy-making in my head is I don’t seem I don’t understand how and I get to some extent, it’s privilege to some extent, it’s never gonna happen to me, but how can we care so little about a profession, that we literally give the power over life and death to? And it’s like, it’s just I don’t know, you know, I mean, it’s, it’s hard for me to conceive of why we don’t think that’s more important.

Radley Balko

So, you know, I come from kind of a libertarian background, and there’s a school of thought in libertarianism called Public Choice Theory. And the idea is that when you take somebody and you give them a job in the public sector, they don’t stop being human, right? They don’t become these sort of altruistic people who only act in the public good, they’re still selfish people like we all are, and they still do things for themselves. And, you know, they’re still going to remember things in a way that makes them look good, rather than bad. And it manifests in ways like, if you’re in charge of a public agency that’s supposed to address this particular problem, it actually is in your interest to not completely eradicate that problem, right? Because then you’re out of a job. And in fact, it’s in your interest to sort of exaggerate the extent of the problem. And so this idea is, you know, that it isn’t sort of an Ayn Randian sort of endorsement of self-interest or selfishness. It’s saying, this is just human nature. And so our laws and our policies should be written and enforced and designed in a way that acknowledges this and sort of that’s built into the system right? We don’t just expect people to act in the best interest of the public all the time. Well, conservatives love this public choice theory. It comes to you know, staffing, the EPA, or, you know, the FDA or the SEC, you know, it’s this idea that okay, well yeah, these people aren’t just gonna enforce these regulations based on a devotion to public service. They’re gonna be you know, jerks about it, and they’re gonna be angry bureaucrats. But then you take a guy at a high school and you give him six weeks of academy training and a gun and a badge and the power to detain and beat and kill people. And all of a sudden conservatives are like, wow, you know, we can’t second guess these police officers, we can’t question their judgment, right? Like, who are you to say that cops are selfish and you know, only act in their own interests? And these are the people who should be more scrutinized, right? These are the people who the laws need to be extra careful about and yet, as difficult as it is to fire a public servant, it’s probably about 20 times more difficult to fire a police officer.

Josh Hoe

At the same time, it’s hard to argue that there aren’t some pretty serious problems with police to start with, there’s kind of a decent amount of police violence against regular folks. I saw a statistic the other day, I haven’t verified it, so I’m not sure this is correct or close to correct. But there’s probably some relationship there that you’re almost as likely to be shot by an officer as you are to be shot during some other kind of criminal encounter.

Radley Balko

I think that’s true, more true for black men. I think maybe that’s what the statistic is. I think I’ve seen that somewhere.

Josh Hoe

Yeah, whatever, though, there’s at least a substantive amount of use of force by police. Not always in the solving of a crime.

Radley Balko

Right. Well, the fact that police also beat and kill white people, is often cited by kind of libertarian types, or moderates as well. You know, when you emphasize the racial disparities and systemic racism in policing, you overlook all these other cases. And that turns white people off. So we should just talk about police brutality in general. Well, I mean, you can talk about both right, we can talk about the problems in policing that make cops accountable, that make them less transparent, that contribute to this lack of, this willingness sort of cover for one another, the whole blue wall thing. And then you could also talk about, you know, the inherent racism in policing. And from the way it was sort of designed and constructed and has evolved over the years, to the way it’s enforced, and the way it was used during the Jim Crow era, and how that evolved into what we have today. So you know, if both of these things can be true, at the same time, you can have problems with policing that affect everyone. And you can have problems in policing in which those problems disproportionately affect, you know, minority communities or marginalized communities. And that shouldn’t be hard to understand. And yet people seem to willfully want to misunderstand.

Josh Hoe

We brought up the Floyd protests several times, you know, one of the biggest public protests in US history, and we still have a lot of police violence. It almost feels like it’s harder to bring accountability measures, and it feels like in a lot of ways police funding has gone up, and I’m not sure reform has gone up within police. Do you have a feel for that, since this is what you do? I see anecdotal stuff.

Radley Balko

It’s a hard thing to measure, how much reform is happening. But I do think actually, you know, in my 20 years on this beat, I think we’ve seen more substantive reforms since the Floyd protests than, you know, at any period since I’ve been covering this. I think there’s been actual reform, we’ve seen entire states like Virginia, as well as I think a few dozen significant towns and cities, ban no-knock raids or implement some sort of restrictions on them; we’ve seen even more places put bans on chokeholds and carotid holds; lots of you know, reforms, a couple of states now have created a kind of workaround for qualified immunity. So there’s now a state cause of action if a police officer violates your civil rights. And you know, if you’d told me five years ago, that we’d seen these kinds of proposals, I would have told you, you’re out of your mind. I mean, I don’t think most people knew what qualified immunity was five years ago. And now it’s like, I’ve seen 60 to 65% of the public support reforming or eliminating it. And similar numbers for ending no-knock raids. So, you know, I think the George Floyd protests did move the needle pretty significantly, and public opinion, less significantly, but still noticeably when it comes to actual substantive reform. You know, I think we have a long, long, long way to go to get to a just and equitable system of law enforcement. But, I’m more optimistic than I’ve been in a long time in terms of what’s happened since the George Floyd protests.

Josh Hoe

As we’re looking into what the answers are, and how we get to those – there’ve been a lot of things that people have suggested. One thing I think that most people seem to have some consensus on, at least people who study this, is that there’s a large body of research that suggests that increased police in particular places at particular times, for instance, like, what are called hotspots have an effect of reducing crime? Does this mean, as I think some people have suggested, that the answer is just to have more police everywhere, or to have more and more surveillance everywhere, to have more tech everywhere, facial recognition, etc?

Radley Balko

Like you said, there is evidence that hiring more police has an effect on reducing crime. You could take that to its logical conclusion and say, you know, well, North Korea has almost no crime at all right? I mean, that doesn’t mean it’s the kind of society we want to live in. The one place I’ve seen the Niskanen Center did a study on what happens when you hire more police officers, and they found that crime does go down, but they also found a corresponding increase in arrests for very low-level offenses. And they factored the damage of those arrested into their analysis, and it comes out, you know, much more, much closer to a wash than you’ve seen in these other studies. The other thing is, we don’t know how long the effect lasts. And if people sort of adjust to what’s happening there are also political and practical considerations, you can’t just saturate every part of the city. I mean, a lot of times, if you crack down on one area, crime is gonna pop up in other areas, that’s particularly true with drug crime, because I mean, drug crimes, like the air in a balloon, right? I mean, you’re never gonna get rid of it, you know, you can move it around, but you’re never gonna get rid of it. And the crime that is associated with that is always going to be here, as long as you have black markets for some types of drugs. There’s also, you know, not a lot of scrutiny on what it is about policing that reduces crime or appears to reduce crime, is it you know, that people in these neighborhoods are intimidated by beliefs? Is it that, you know, these arrests are taking people off the street? You know, John Pfaff has suggested and I think he makes a compelling argument that it’s, it’s what he calls the Sentinel Effect. It’s just the fact that when people are watching, people are less likely to commit crimes. Well, does that mean you could achieve the same effect with, you know, neighborhood watch groups or, community crime, you know, anti-crime community groups, or a private security system, officers and agents, security officers, or, you know, violence interruption groups? We don’t know. And, certainly, if we can have the same effect on reducing crime without the accompanying destructiveness and damage that policing does to marginalized communities, that’s something we need to look into. And I think a lot of reformers have made this point, that a lot of people are really kind of critical and down on these violence interruption groups because the academic research isn’t there to support, you know, that we don’t have overwhelming academic research that says this works. [But] What research is out there, I think, suggests that it’s definitely worth looking at and investing more money in it. You know, the amount of money you have to invest to get the same deterrent effect that you get from policing is minuscule by comparison. So it’s certainly something we want to look into. But a lot of reform people…

Josh Hoe

I don’t want to kick back too much. But I know that for instance, in Patrick Sharkey’s research, he suggests that fairly banal investments and a bunch of different things that happened in communities can have pretty outsized effects, and that an opportunity cost of increased funding for policing is probably these community programs. So I do think that there’s particular programs like I think there’s one in Denver, that they’ve been putting in social workers where police would normally go in that’s been quite effective.

Radley Balko

So yeah, I was working my way up to that. So the CAHOOTS program, which started in Eugene, is now in Denver, and about a dozen cities across the country, and has been enormously successful. And this is where, yeah, they send a mental health professional when someone calls 911 because somebody’s having a mental health crisis, instead of, you know, a SWAT team. And believe it or not, you know, when you send a therapist, instead of a SWAT team, you’re less likely to have bad results. And not only has it been successful, you know, overwhelmingly successful,they never even needed to call the police, in some 99 plus percent of cases, the police were never even necessary. So that’s, you know, that’s one example. You know, I was talking more about the Cure Violence type groups, which I’m not down on at all. I think we do need to invest in the research that is out there.

Josh Hoe

The violence-interruption kind of stuff?

Radley Balko

Yeah. And it’s not conclusive yet, but it’s certainly encouraging. And, you know, the argument that reform people made, that I think is pretty persuasive, is if we held these groups, violence interruption type groups, you know, if the standards that sort of moderate and tough on crime people are holding these groups to like, we must have over overwhelming academic research before we fund them, that same standard, you know, we wouldn’t get policing any money at all. We just kind of accept whatever research is out there that says more cops equals less crime, and we don’t really question it all that much. Whereas, you know, we give heavy scrutiny to these violence interruption groups, even though the research that is out there does show that they prevent crime.

Josh Hoe

I know you’ve written about this a lot. So I think this seems like a good place to throw this in there a little bit, you know, you’ve got police in place, time, and manner. In one element, maybe the problem is what you’ve written about, which is kind of the over-militarization of the police. Does that play into this as well?

Radley Balko

Yeah, so there are two sides of militarization. One is the stuff, right? So the guns and the ballistics gear and the tanks and armored personnel carriers, all that. And, you know, there’s a time and place for some of that stuff. Some of it’s ridiculous and unnecessary and excessive. But the flip side of that is, is the mindset, right? The militaristic mindset, this idea that it’s cops versus everybody else, you know, that the cities that they serve aren’t, you know, cities, they’re battlefields. And, you know, they do whatever they have to do to get home at night, right? They’re not serving and protecting people. They just, they’re just surviving, and that’s a really bleak outlook on the world and on the people whose rights they are supposed to be protecting. But this is kind of the mentality that you see; you see it in, you know, police message boards and police websites, that phrase, you know, whatever allows you to get home at night, you’ll see some version of it over and over and over again. You see it in police culture, police t-shirts, the patches that they wear, the challenge coins that they issue, you know, a lot of skulls and crossbones and grim reapers and you know, death in general.

Josh Hoe

A lot of use of the Punisher.

Radley Balko

Right, the Punisher stuff absolutely. The vigilantism. And you know, a lot of just disrespecting the people, you know who they’re supposed to be protecting. again, there’s that study that one of the nonprofit groups did, I think Politico published it a few years ago that found that something like one in five police officers in the cities that they looked at had posted something either racist, misogynistic, or glorifying violence on their social media pages, you know, one in five was a lot. And, you know, those are the ones that they found. So, you know, we’ve seen, we’ve also seen this, anytime there’s been like investigations into police texting and emails, I mean, you find it, you know, over and over and over again, no matter what the Manhattan Institute tells you. There is rampant racism and bigotry in policing. And, you know, it’s something we need to, there’s a problem with police culture, I think, in this country, and I think part of it is this isolation I talked about earlier, where, you know, police just kind of see themselves as constantly under attack. And, you know, see that the only people they can really trust are other cops in their families, and it’s them against the world, and it’s just, you know, it’s really unhealthy for the people that they’re supposed to be protecting, but it’s also just, what a miserable way to go about your day to day work life, right? You see yourself at war with everyone. You’re driving around in your squad car. And the only interactions you have with other people are confrontational, right? I mean, imagine that that was your work life. And it’s sort of like, if you were, if Twitter were sort of brought to life and your everyday interactions, you know, in the physical world, you know, it’s kind of a miserable way to live. And no wonder a lot of cops are kind of angry and cranky all the time.

Josh Hoe

We have another element of this, so you’ve got maybe militarization [as] a problem. Another problem, it seems to me, at least for most of the research I’ve read – we can talk about if police deter or don’t deter – but one thing seems to be true when it comes to serious crimes. Clearance rates are relatively low and a lot of people, even when we’re talking about people who’ve been incarcerated, there’s a gigantic amount of people who’ve committed the same crimes who never get arrested for anything.

Radley Balko

Yeah. And look, this is one thing I’ve tried to point out over and over again, is that in every city where we’ve seen massive sort of protests, where one incident spurred you know, huge protests. Well, there’s Baltimore, Freddie Gray, you know, Ferguson and Michael Brown, Philando Castile, George Floyd, you know, every one of these cities has a long and documented history of police abuse, corruption, and racism. You’ll find, you’ll probably find a DOJ study on every one of these cities, Chicago, Baltimore, these are also all the cities that not only have high, you know, exceptionally high crime rates, these are all cities where crime never really went down while it did in the rest of the country. And you know, I think those things are all related. I don’t think that any of those things should surprise us. If you have a police department that has a documented history of abuse and racism, particularly against marginalized communities, which we’ve also seen in a lot of these cities, they have extremely low clearance rates, especially in marginalized communities. Well, if you live in one of those communities, you have a police department, you know, that has probably beaten or wrongly arrested or harassed, you know, either you or your family or somebody you know, or some combination of those three, and they’re not solving any crimes. I mean, of course, you’re not going to trust the police, right? What are they doing for you? Right, all they’re doing is harassing you, when you actually need them to, you know, because you got mugged or somebody stole your car, broke into your house or, you know, robbed the convenience store down the road that you use, they’re not solving those crimes. So they’re not, you know, people don’t trust them. And, I mean, the other problem that we’re seeing in a lot of these cities, and it’s rocking places like Memphis right now, is they can’t recruit, right? Nobody wants to go work for these police departments. Because, you know, if you live in, in one of these communities that’s had to deal with police, the last thing you want to do is go work for, you know, a police agency. And this place in Minnesota I talked about, they’re having a very difficult time recruiting people. Their officers are leaving for entirely different reasons, right? So you’ve got white officers leaving, particularly in bigger city police departments, because they don’t like reform, they don’t like working for black chiefs, they don’t like accountability, they don’t like transparency. But you can’t replace those officers with black officers, because the legacy of these departments in the communities that you’d be recruiting from is, you know, abuse and corruption and harassment, and nobody wants to work for that department. Nobody wants to be the guy, you know, from the neighborhood who becomes a cop, you know, if that neighborhood has been abused by police for the last 20 years, so we’ve got a kind of a crisis right now, in policing. And, one way to solve it, I think, is to take a page from the abolition movement. I should say, I’m not an abolitionist, but, you know, they have done, a lot of abolitionists have done the work, they have done the research, they do have sort of, you know, interesting ideas that we should at least be taking a look at. And, you know, we don’t have to abolish the police, but we could definitely shrink the footprint, especially if the logistics of what policing looks like right now makes that a necessity. So, you know, maybe we stop low-level drug arrests, maybe we stop putting police in schools and on subways, on public transportation. And we start, you know, spending more resources on solving crime and, you know, developing relationships with communities and doing sort of quality of life improvements that don’t involve, you know, stop and frisk and suspicionless searches, you know, we’re gonna have to figure out something to do with fewer law enforcement officers, because if people are quitting, because they don’t want accountability, and they aren’t able to find cops to replace them, we’re going to have to start prioritizing.

Josh Hoe

I mean, there’s also a structural problem, where we’re just going to, because of the demographics of the situation, right now, my understanding is we’re going to have, in almost every field, we’re gonna have shortages in the workforce. I think it’s, it’s something that we’re going to have to address, you know, and I think the…

Radley Balko

We could also, you know, let in more immigrants, and that would help a lot of these problems. But we don’t want to do that either, apparently.

Josh Hoe

And I think it’s funny, you bring that up because it kind of leads us to the politics of the thing. Because, you know, in election after election over the last year, we’ve seen, and I can show you the heat maps, you know, where the communities that are most impacted tend to vote for reform. And the communities that are least impacted tend to vote for a kind of traditional law and order message. And so how are we going to be starting with the people level? Do we have any ideas of how we’re going to start threading the needle of getting, or even trying to get people on the same page about why we need to change and what needs to change?

Radley Balko

I think we don’t even fully understand, never mind sort of comparing, you know, people who vote for traditional policies versus reform policies. We don’t even know why people who vote for reform policies vote for those policies. I mean, you look at polling, you know, lots of people were pointing this out before me, but you know, if you look at polling of black people, for example, they support, you know, massive reform, polling shows that black people fear police more than they fear criminals. You know, they think that police are often unfair, they think the system is racist, and they want more police officers and more spending on police right? And you know, people on the right have said oh, yeah, this just proves that all your reformers are full of shit. You know, black people want more cops, you know, hahaha, defund, hahaha. No, what it shows is that black people want to not live in crime-ridden communities and they don’t want to be harassed by police. I mean, that’s not that hard to understand. And yet, like people seem to see, seem to look at those poll results and think they’re contradictory. They’re not. I mean, people want to feel safe. They want to feel safe from criminals, they also want to feel safe from police. So, you know, you can interpret those polls, as black people want more money and more cops, or they just want police themselves to be more effective when they are there and less harassing.

Josh Hoe

Although I’m not just talking about polls, I’m talking about election results, like what just happened in Chicago, what’s happening in Pennsylvania.

Radley Balko

I’m saying if you look at those election results, though, those same people, those same communities also will tell pollsters they want more police, so they want more spending on police. But I think what that’s saying is they want safety and protection. And they and the rest of us have been told over and over again, that the only way you get more safety and more protection is by having more police. Like we’re not, we’re not told that there may be other options, right? We’re not told that investing in some of these other programs may have the same effect without the, you know, the collateral damage.

Josh Hoe

And then there’s the problem of police culture, you know, how do we start? Is there a way that?. . I’ll give you an example, Recently, I was asked to start trying to formulate a policy or policies for how to reform jails. And my initial response was that if you go at it in a regulatory manner, the sheriffs are mostly just gonna ignore you. And that, in a lot of ways, what you have to do is find ways to get them to think it’s in their interest to do reform. And I’m not really even sure how I’m still in the process of sussing out how that happens. What are your thoughts on how you get into police reform from the police side?

Radley Balko

Yeah, I don’t know that. I mean, that’s difficult. You know, I don’t, you know, have a lot of sway with law enforcement. So I haven’t been . . . I think leadership matters.

Josh Hoe

They probably dislike you more than me, but only because you’re more known.

Radley Balko

Yeah, I mean, look, there are police officers who have signed my book at police academies. And it was always, you know, flattering to hear but yeah, I would guess that the leaders of most police unions, if they know who I am, probably, you know, don’t like me. But yeah, I think leadership matters. There was a study that just came out about two years ago, finding that in big city police departments that have a black police chief, there’s something, some dramatic number, like 60%, fewer shootings by police officers. So you know, I do think having good leadership matters, but you also have to have the kind of institutional structure in place where a police chief is going to be able, a good sort of Chief that understands all of this or kind of gets it, is going to be able to implement their policies. So I’ve written about a number of, particularly black chiefs, but not just black chiefs across the country, who were reformist, who, you know, didn’t last more than a few years, because the union had an incredible amount of power to chase them out. People on the city council managed to sort of push them out, or they weren’t allowed to hire their own command staff, because you had, you know, some of the Civil Service protections [who] were the old guard, it was impossible for them to get rid of them. And so the old guard sort of brought them down from the inside and made it impossible for them. So I do think leadership matters. And I think we’ve seen lots of good examples where leadership matters, but the leaders need to be able to lead right? you have to take away the institutional barriers so that they can change the culture. And that’s, you know, that’s a difficult thing to do.

Josh Hoe

I think the third part of the chicken/egg, egg/chicken, is kind of the media’s part in all this. You know, I mean, especially in a world in which a lot of police departments have the money to have media divisions and things like that. And we have decades of tough-on-crime kind of reporting, and if it bleeds, it leads, etc. Do you have any thoughts about how we approach the media landscape of all this?

Radley Balko

Ah, yeah, I mean, I think it’s hard to make sort of blanket statements about how the media covers criminal justice because in some ways, I think these issues are being covered better than they ever have before. I think you have more outlets that are doing serious investigative journalism, I think you have more, there are more platforms for people who are critical of law enforcement, are critical of the current system, to be heard. From podcasting to social media to you know, there’s just, there’s a lot of ways to get the word out. You know, I think there are some problems that persist, particularly in small towns or where you only have one newspaper. If you’re a beat reporter your job is sort of contingent on police cooperating with you and so it’s going to be difficult for you to be critical or skeptical or ask you know, tough questions. I think that problem continues and it gets worse, as media outlets fall. And then, you know, like you said, I think the “if it bleeds, it leads” problem, for a long time, crime fell for a very, very long time for about 20-25 years. And, you know, there were some kind of long-term trend pieces about that. But when it fell, you know, in the aggregate, it fell by, you know, an incredible amount that criminologists still really can’t explain. But year to year, it wasn’t that much. So we didn’t get a lot of stories about how crime was falling. But then the second it goes up even a little bit. It’s like, Oh, we’ve reversed this 20 years [trend], something’s terrible, that’s gone wrong. And I had worried about this. I mean, the first 15 years I covered this, crime continued to go down and it became easier and easier to sort of advocate reforms. Because, you know, the reality, the sort of real politics of the situation is that if crime is low, it’s a lot easier to implement reforms, and I worried what would happen when crimes are to go up again, you know, we would see if we would see a return to kind of the 80s and 90s. And the sky is falling, you know, coverage. And, you know, we have seen some of that. I also think there’s a lot more pushback, though. And, you know, I think every time, New York Times posted something that, you know, maybe where they take maybe take one sensational crime and report on it in a way that suggests it’s representative when it isn’t, or, you know, they quote some politician about blaming bail reform for an increase in crime, like there’s immediate backlash. And, and, you know, I think the Times has also done a lot of good crime reporting and good coverage as well. So yeah, I’m, I don’t know, I’m hesitant to kind of make a blanket statement about whether the media is good or bad about this because I think it’s kind of all over the place. I think, you know, I think it’s good for pro-reform people to continue to call out bad coverage when they see it. You know, I think, for example, you know, the coverage in San Francisco was horrific. And there was this kind of pile-on and you saw, you know, people who were willing to kind of join the pile-on got more attention and more clicks and more eyeballs. So there’s an incentive to sensationalize and disincentive to push back. But in other places, you know, I think the incentive may be reversed. I think there’s, you know, people like contrarian takes, so I don’t know. Yeah, I’m rambling a little bit, but I think it’s kind of a, I think I’m rambling because the answer is kind of all over the place. I don’t think there’s any.

Josh Hoe

It’s a lot more nuanced than just media bad, media good. But I do think that a lot of times even with people who are trying to do good work, that the ability of police departments to immediately get their stuff in there makes it harder to fight back. And sometimes reformers are presented kind of as the straw people, but I do agree there’s a lot more genuinely good coverage than probably when I was younger, and stuff like that. I agree with that.

Radley Balko

Yeah. And I think local media is particularly bad. I mean, local TV news is maybe the most frustrating part of the entire industry, because there is this, there’s the sensationalism aspect. There’s the “what drugs your kids are taking now” stories. You know, there’s the ride-alongs with the SWAT team that kind of glorifies this kind of, type of policing. And there’s just like a, you know, there’s the, it’s access problems, right, when you’re a local TV reporter. You know, the police are a great source, you know, they’re gonna give you crazy stories and scary crime stories that scare parents. And so they’re gonna tune in and watch. And so yeah, there are a lot of great local reporters out there, too. But yeah, I think, you know, particularly as we lose more and more local media, the problem gets worse.

Josh Hoe

Oh, one thing I’ve been trying to do this season is to let people get to know my guests a little bit more. Do you have any hobbies? I know, it’s kind of a weird question, and might not my best segue, but.

Radley Balko

Yeah, I do a little amateur photography. What else? Well, we have two very old dogs.

Josh Hoe

My dog is actually sitting right over here watching me do this interview.

Radley Balko

Yeah, we used to do, I mean, I love to travel, then less of that, since the pandemic. I’m hoping to start up again and do a lot more, especially international, I’m itching to get out of the country.

Josh Hoe

Do you have any particular favorites so far, places you remember?

Radley Balko

Oh, well, I mean, the places I want to go, the places I’ve been that I loved, I really like Croatia. I’ve been there twice. It’s kind of a poor man’s Italy. And I mean that in a really good way. I mean, it’s, you know, it’s gorgeous, beautiful. It’s interesting. But it’s really inexpensive and also has the kind of morbidly fascinating history of the Balkans War. You know, the scars of it are still there. Let’s see where else? I love Slovenia, Prague, Budapest. I really love Budapest.

Josh Hoe

You’re making me happy. I’m Hungarian.

Radley Balko

Yeah. I mean, unfortunately, the, you know, the politics in Hungary are pretty horrible, right?

Josh Hoe

Yeah, I’m not saying that I want to go to Hungary right now.

Radley Balko

Yeah, all the right-wingers are there living it up. But Budapest is such a beautiful city. But yeah, I don’t know. I haven’t been to Italy yet. I really need to go there. I’d love to go to Japan at some point. Let’s see where else? My wife and I went for our honeymoon to Southeast Asia. So Hanoi was amazing. Cambodia is a really interesting country with lots of just really warm, wonderful people. Yeah, I don’t know. My wife’s family is from Colombia. And I have not been there yet. But I’m excited to go soon, I hope. Love to go to the Baltics, Sweden, Norway, Denmark, then Latvia, Lithuania, you know, that sounds like a fun trip.

Josh Hoe

Sounds like kind of a lot of stuff to, a lot of travel to plan here.

Radley Balko

Yeah, I mean, I think I have a kind of Anthony Bourdain approach to the world, which is, you know, you should go and eat people’s food and enjoy their hospitality and get to know people. And it’s, I mean, one of the most telling things I think about Trump is that he absolutely hates traveling to other countries. And I remember, I can’t remember, a magazine interview or something. He said, he’s been, you know, his wife Melania is from Slovenia. And he went to Slovenia once, he apparently didn’t even want to get off the plane. And he talked about what a dump it was and like, Slovenia is just a wonderful country. I would love to go back there. It’s beautiful and mountainous and the people are just extremely welcoming and kind and Ljubljana, the capital, is like, there’s graffiti all over the place, but it’s like, beautiful in its own way, expressive and interesting. And I absolutely love that. But [was it] Mark Twain, maybe who said that you know, travel cures you of your prejudices because you get to, you know, experience people and different cultures. And you know, it’s knowing your place in the world.

Josh Hoe

That might explain why he didn’t want to get off the plane.

Radley Balko

Yeah, that’s true. Good point. Yeah, I mean, the pandemic robbed a lot of us of that. And, you know, I think that may contribute to all the kinds of social strife and general kind of despair that we see. It’s like, we’ve had less opportunity to get to know other people and expose ourselves to new and interesting things.

Josh Hoe

I always ask if there are any criminal justice-related books that you like, or might recommend to our listeners; do you have any favorite books?

Radley Balko

Um, probably not that your listeners haven’t already read. But I mean, actually, you know, one book that’s pretty old at this point, but I really love it, and it really informed a lot of my thinking about the drug war was Smoke and Mirrors by Dan Baum. And when I say it’s old, it’s like 25 years old, or the mid-90s. But it traces the history of the drug war, you know, back to the Nixon administration, and he interviewed, you know, a lot of the people in that administration, and he talks about all brings it up basically through I think, the Clinton administration, but it’s just such a, you see, you see kind of the, it’s a narrative that describes the slow motion train wreck that is the drug war, you know, page by page meticulously, and you know what’s going to happen later. So you’re like, No, no, don’t let this happen. And it’s just, it’s really well done.

Josh Hoe

We’re doing it again with fentanyl.

Radley Balko

Exactly. Baum died a few years ago. But that book is, you know, was kind of the inspiration for Rise of the Warrior Cop, the way he went about telling that story was kind of the template that I use for my book as well. So that’s, that, I think, is just a wonderful book. I mean, it may seem a little dated at this point, although frankly, I mean, the roots of the drug war, it’s still important, still important to know, you know, where all this bad policy came from and where it started.

Josh Hoe

And where can people find you, find your Substack? You’ve mentioned it before, but just if you want to plug it again, and your Twitter maybe?

Radley Balko

Sure. So the Substack is called The Watch, but it’s radleybalko.substack.com. Or if you just Google my name, I’m sure it’ll pop up. And you know, my income, the vast majority of it comes from subscribers now. But it is free. Everything’s free. So I just ask that you know, if you liked the work and think it’s important if you’d subscribe for, I think it’s six bucks a month. That helps me continue to do the work. But it’s also all available to the public because you know, there’s no reason to do this work if people can’t read it.

Josh Hoe

Yeah, that makes sense. I always ask the same last question: what did I mess up? What questions should I have asked, but did not? And this is really just a chance for you to talk about anything else that you want to talk about, you know?

Radley Balko

Wow. Well, let’s see. Well, you should have asked me about my wife, who’s also a great investigative journalist and does incredible work. And in fact, her work has gotten two people out of prison in the last few years.

Josh Hoe

I didn’t even know that was the case.

Radley Balko

Yeah, both on death row. And in fact, she had a podcast about another case in Georgia. That guy’s out now too. So yeah, Liliana Segura. She writes for The Intercept and does incredible work.

Josh Hoe

Ah, so, that was your wife? I’ve definitely read some of her stuff.

Radley Balko

She’s also kind of my editor right now, while I’m self-employed, so I have to plug her I think.

Josh Hoe

So that’s a pretty good gig, you got kind of full circle there for both of you. Do you get, I assume you edit her stuff to some extent?

Radley Balko

Well, she kind of edits my stuff for the Substack. Because I don’t have another editor to look at it. You know, she has great editors at The Intercept. But yeah, I mean, I read her stuff and offer feedback. And yeah, it’s definitely a mutual thing. But yeah, I’m much more reliant on her editing than she is on mine right now.

Josh Hoe

Well, thanks so much for doing this. I really appreciate you taking the time.

Radley Balko

Yep. Thanks for having me. Take care.

Josh Hoe

And now my take.

After 50 years, trillions of dollars wasted, hundreds of 1000s of people incarcerated, foreign countries invaded, and with overdoses worse now than ever before, you would think people would get serious about trying something different. But of course not. When it comes to the drug war it never ends, it will apparently never end. The war on drugs is a war on people. And it just keeps going and going and going. And a lot of that is because we the public just can’t get enough of believing that incarceration is the best answer to addiction, despite the fact that that has never, ever, ever, ever worked. It’s never worked. It’s time for us to move on to trying some new solutions that actually help people with addiction, as opposed to simply doubling, tripling, quadrupling, quintupling down on a failed solution.

As always, you can find the show notes or leave us a comment at decarcerationnation.com. If you want to support the podcast directly, you can do so from patreon.com/decarceration nation. For those of you who prefer to make a one-time donation, you can now go to our website and make a one-time donation. Thanks to all of you who have joined us from Patreon or have given a donation. You can also support us in non-monetary ways by leaving a five-star review from iTunes or add us on Stitcher, Spotify or from your favorite podcast app. Make sure and add us on social media and share our posts across your networks. Thanks so much for listening to the DecarcerationNation podcast. See you next time.

Decarceration Nation is a podcast about radically re-imagining America’s criminal justice system. If you enjoy the podcast we hope you will subscribe and leave a rating or review on iTunes. We will try to answer all honest questions or comments that are left on this site. We hope fans will help support Decarceration Nation by supporting us on Patreon.