Joshua B. Hoe interviews JJ Prescott and Wayne Logan about their book, “Sex Offender Registration and Notification Laws, an Empirical Analysis.”

Full Episode

My Guests – JJ Prescott and Wayne Logan

J.J. Prescott is Henry King Ransom Professor of Law, University of Michigan. Prescott publishes broadly on criminal justice issues, employment law, and civil litigation, often using empirical tools and data to inform controversial policy debates. Prescott codirects the Empirical Legal Studies Center and the Program in Law and Economics at the University of Michigan.

Wayne A. Logan is the Steven M. Goldstein Professor of Law, Florida State University. He is an elected member of the American Law Institute and a past chair of the Criminal Justice Section of the Association of American Law Schools.

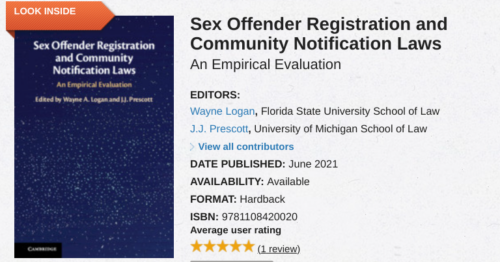

They are the editors of the book “Sex Offender Registration and Community Notification Laws: An Empirical Evaluation”

Watch the Interview on YouTube

You can watch Episode 130 of the Decarceration Nation Podcast on our YouTube channel

Notes from Episode 130 JJ Prescott and Wayne Logan – SORN

You can find JJ and Wayne’s book “Sex Offender Registration and Notification Laws: An Empirical Analysis,” from any bookseller.

JJ co-authored the paper, “Do Sex Offender Registration and Notification Laws Affect Criminal Behavior?” with Jonah Rockoff in 2011.

You can find the American Legal Institute Model Penal Code for Sexual Assault and Related Offenses on their website.

Here is a good article by Professor Ira Elman discussing the ALI Model Penal Code changes.

The three books that JJ and Wayne recommended were:

Colson Whitehead, The Nickel Boys

Wayne Logan, Knowledge as Power

John Pfaff, Locked In

Full Transcript

Joshua Hoe

Hello and welcome to Episode 130 of the Decarceration Nation podcast, a podcast about radically reimagining America’s criminal justice system.

I’m Josh Hoe, and among other things, I’m formerly incarcerated; a freelance writer; a criminal justice reform advocate; a policy analyst; and the author of the book Writing Your Own Best Story: Addiction and Living Hope.

Today’s episode is my interview with JJ Prescott and Wayne Logan about their book, “Sex Offender Registration and Community Notification Laws an Empirical Evaluation.” Wayne Logan is the Stephen M. Goldstein Professor of Law at Florida State University. He’s an elected member of the American Law Institute and the past chair of the criminal justice section of the Association of American Law

Schools. JJ Prescott is a Henry King Ransom Professor of Law at the University of Michigan. Prescott publishes broadly on criminal justice issues, employment law, and civil litigation, often using empirical tools and data-informed controversial policy debates. Prescott co-directs the Empirical Legal Studies Center and the Program in Law and Economics at the University of Michigan. Together they compiled and edited the book Sex Offender Registration and Community Notification Laws: An Empirical Evaluation, which we will be discussing today. Welcome to the DecarcerationNation podcast, Wayne and JJ.

JJ Prescott & Wayne Logan

Thanks so much for having us. Thank you, Joshua.

Josh Hoe

Yeah, it’s great to have you here. I always ask the same first question. And since there’s two of you, you’ll get two chances to answer it. But it’s how did both of you get from wherever you started in life to where you were doing research and writing a book about sex offender registration and notification laws? And I realize that’s a very broad and open-ended question. But I like everyone to get to know our guests. So either one of you can start.

JJ Prescott

I’ll let Wayne [start]; when I started working in this field, he was already a giant. So I’d love to hear his story.

Wayne Logan

Alrighty, so thank you, JJ. So I don’t know if you want my professional life. But it was pretty typical of a law professor. I went to law school and then clerked for judges and practiced law for a while. And then I found that I was doing a part-time teaching job while practicing, I found I really liked teaching law school. And so I got into the law teaching racket. This is my 25th year. And so I actually started my initial interest really, just after I started teaching and writing papers in 1997. And it just caught my eye, the issue of sex offender registration and notification. It hadn’t been litigated for the US Supreme Court yet. Legal issues were being decided by lower state and federal courts. There’s really a lot of [ripe] issues still, but it struck me as, you know, one of the major civil liberties issues of our time, and a kind of a cornerstone in contemporary efforts to extend the carceral state, so to speak, outside prison walls. So that was what initially interested me. And I’ve continued to research and write about it for all these years. How about you, JJ?

JJ Prescott

Yeah, maybe it’s not too different. Although when I showed up, there was a lot more work. And there had been a lot more litigation in this space already. But I came to registration notification laws, as initially sort of excited by the idea of something new in the criminal law. So you know, as a criminal law teacher, there’s a lot that stays the same. And for a long time, the primary way we’ve tried to control and punish has been through incarceration, and occasionally through fines. And suddenly, there is this idea that we can use information and perhaps deputizing the public in certain instances to try to improve public safety. And, to me, that was an exciting idea. In the time since then, I’ve come to realize that it is really more in the direction that Wayne described it that, you know, this is kind of a growth of the carceral state and, and the fact that technology and information can be used in a way that essentially lowers the cost of social control is something that we ought to be very worried about and pay particular attention to. But in any event, at the time I started researching in this area, it seemed that economists had not yet gotten to the sets of questions and the data. And the laws and litigation existed to try to do something really rigorous to understand the impacts of these laws on criminal behavior. And so I dove in at that point and spent a lot of time trying to get a handle on what these laws look like, from state to state.

Josh Hoe

I never like to be accused of burying the lede. So I’m going to start with this: given the data, a lot of what we seem to be facing, and an underlying premise in the book, I think, is this notion that a lot of our responses ultimately have a lot more to do with emotion than data or logic? How do you both approach your part of this work, given how committed people and legislators seem to be to emotion and punishment, and not really as concerned with the data necessarily? If that’s a fair claim, which it may not be.

Wayne Logan

So I’ll go again first. So one of the unique things about SORN, which is short for Sex Offender Registration & Notification, is that roughly for a decade, no one really looked at it empirically [or] analytically, and it just struck me as a real outlier, because a government program or programs of its size, not to have been assessed, struck me as kind of unusual. And gradually over time, in other words, it was accepted as an article of faith that these laws worked, which troubled me just as a matter of principle. But over time, there’s been evidence accumulated, and JJ has contributed mightily to that body of research, looking at various aspects of the law. And you know, what we tried to do in this volume was really in a kind of concise way, in an accessible way, kind of put together research from really the leading researchers in these particular areas, within eight or so chapters in the book. They really just tried to lay it out, not be advocates, but just try to be as objective as possible and provide the information for policymakers to consider – hopefully, they’ll consider – when they’re thinking about the laws and whether to tweak them, whether to retain them, etc. So that’s kind of where I was coming from when we were thinking about putting together the book.

Josh Hoe

And, JJ, do you also just look at it as an objective thing that you’re trying to do? Or ultimately down the road, do you think that that’s something that researchers have to come to grips with? Or is it just something that’s just going to have to play out the way it plays out?

JJ Prescott

I mean, it’s a great question. I mean, I’ve tended to try to stay in my lane with my research. I mean, the outcomes I’ve been particularly interested in, although there are plenty of others that policymakers ought to care about, have just been the effects of these laws on recidivism and crime generally. And my thinking from the perspective of like, what would legislators care about is that at the end of the day, these laws are expensive. There are a lot of opportunity costs that come with trying to enforce them and keeping people on these lists. And if they really don’t make the public safer, then that struck me as the type of argument that legislators, even those who are particularly interested in punishment, and who care less about, maybe the individuals who are affected by these laws, would care about. In other words, if it turned out that these laws actually didn’t make things any safer, or maybe even made things less safe, that might be the sort of move that would affect the votes on these kinds of laws. And, you know, a lot of times I feel like people in this space focus on, for example, the rights of registrants, the dignity of registrants, and all of those things are important to me as a potential voter, but I think they are unimportant to many people who are making decisions on these questions. And public safety at the end of the day is the real issue. You’ve raised another question, which is, well, maybe actually public safety doesn’t matter as much as I thought, that if you actually said, Well, you know, if you want to punish people in a certain way, it’s actually going to make the world less safe, you are more likely to be the victim of a of a criminal offense if you decide the way to go is to punish people to this extent. I’m sure there are people in that category. But in trying to target my resource towards what I thought would be most likely to move the needle in a direction I thought was positive, right, whichever way that happened to be, whichever way the work came out. The focus for me was on criminal behavior because that’s really at least what these laws are supposed to be about.

Josh Hoe

So this question is for JJ. Right now, we seem to be at a place where people are, not just in this area, but in all areas, very skeptical of science and research, almost to the point where they’ll accept anecdotal data, often in play, you know, prefer anecdotal data to actual good datasets, etc. Often, you’ll hear people say things like, well, you can make a study conclude anything; I’ve had this conversation with relatives. Would you like to talk about the existential things that you all face as database researchers right now? it seems like this is maybe not specific to this book, but something specific to the kind of work you do.

JJ Prescott

I’m happy to jump in on that one first Wayne. So I mean, this kind of question terrifies me, because it’s sort of a question that suggests that for some people [that] facts, facts just don’t matter. And I mean, I think that the best response is generally, maybe in the same way that I used to answer people who would complain that there are too many lawyers in the world. And I would say, well, there are not enough good lawyers in the world. And I would say the same about empirical research: well, you can come up with ways to manipulate arguments, even with numbers that we have, we have an entire set of institutions designed to root out and stop those kinds of manipulations from happening at universities and through the tenure process, and through the peer review process as well. And so I think, I think a good careful reader ought to be careful about any individual study, which is one of the reasons why, you know, Wayne, and I went into the direction of, let’s not focus on a single paper here, what we ought to be focusing on is the large corpus and the broad group of researchers who’ve basically all taken many different types of methods, many different approaches and have come to very similar stories and what they see out there. And for me, that’s the answer. The answer is we have a lot of checks and balances built into what makes it through and continues to make it through and to become part of the canon of what we consider to be, you know, quality research.

Josh Hoe

And Wayne, you know, JJ is talking about, you know, there are a bunch of standards, and you can determine between good and bad research. And obviously, that’s the way I approach things; I luckily had some scope and methods classes and things like that. But how would you communicate to kind of normal folks, you know, how they can find or how they can identify what is good research?

Wayne Logan

Well, it’s kind of outside my wheelhouse. I’m a law and policy guy. But I would just kind of follow up on what JJ was saying earlier is that I think the book comes, comes to us at a really important time, because, as you say, unfortunately, policy has been resistant to facts of late, dogmatically so, and actually that’s consistent with what’s happened with criminal justice policy, more generally, there’s been kind of a disregard or disavowing of experts, quote, unquote, with respect to this particular policy, intervention, SORN. You’ll see folks saying like, of course, it works intuitively, it has to work. And by the way, if only one child is saved, I’m all for this. And so when you have that kind of a mentality with respect to the laws, it makes them very difficult to tweak or change. And combined with that, many of the laws, of course, are named after individual victims. And so, you know, any politician who wants to, you know, be critical of the laws runs the risk of not just being, you know, pro-sex offender, but also anti-this victim. So, what we have here is we tried to position the book to provide the best research we think is out there on these particular aspects of SORN and let policymakers, and judges and lawyers and citizens make the decision about whether this is a good way to spend our resources, or, in fact, whether it’s perversely criminogenic, that it may actually be causing greater recidivism among sex offenders, which of course, we can talk about later if you want.

JJ Prescott

I want to stress that I think one of the aspects of this particular debate is that maybe, maybe it’s not super uncommon, but here, I think the common sense first reaction, as Wayne mentioned, is, well, these laws gotta work, how could they make things worse, right? Maybe they don’t work super well. But they’ve got to actually make a difference. Having somebody’s name on a list, it’s got to make it easier to find them. And letting people in their neighborhood know who they are has got to mean that at least a few people will be watching. And, and, you know, even I came to this set of laws in that kind of mindset that the common sense reaction here seems to be like, how could it make things worse? And I think a simple conversation, well, I won’t say it’s simple, but a conversation where we start to bring in, for example, reentry ideas, that when people return from prison, for example, one of the things we try to do is to get them to reinvest in life to give them opportunities to improve their ability at leaving that life behind them. And then to point out that these laws really seem to be doing the opposite of that. And so to the extent you believe that there are ways to reduce recidivism with respect to other crimes, it’s worth noting that we’re not doing that, we’re actually doing the opposite when it comes to people who have been convicted of sex crimes and, and that kind of dynamic approach, making life tough for people through monitoring, and lots of procedural burdens, and so on, has real documented consequences in every other domain where we look at this sort of thing. And so there is actually a tension here, an empirical question, when you first, when you wind up thinking about it, maybe this helps a little bit. But does it help enough to compensate for the potential consequences of these laws in terms of well-known risk factors for returning to crime?

Wayne Logan

And I think also, just another point to emphasize, is that it’s really kind of a zero-sum game, because every dollar that’s spent on SORN, is a dollar that’s not being spent on perhaps more efficacious interventions. And if that’s the case, you know, that’s something that public policymakers should keep in mind when they’re looking at how to best try to ensure public safety. You know, one of the things I would add is that just the uniqueness of these laws, so, as many listeners might be aware, in addition to SORN, there are residence exclusion zones in many states, and many, many more localities. And basically, those residence exclusion laws piggyback on SORN release or registered status. And so the idea there is that a registrant will, you know if they’re going to recidivate, they’re going to particularly focus on children, they’ll do it in their neighborhood. So these laws prohibit registrants from living within 1000 feet, 2000 feet of a school, a playground, or what have you, what people don’t really realize is that, in addition to having very, very questionable efficacy, is that they’re at cross purposes with registration. Because if an individual is not going to be able to live with his mother, or wherever it is, because it’s within 1000 feet of the school, they’re going to be less likely to be candid about where they’re living. And that, of course, is the premise of registration, that police officers and members of the public know where individuals live. So this is another example of how unique these laws are that people are just so wedded, determined to, you know, essentially be focused on this sub-population, that sometimes, you know, it’s incoherent and the policies can be at cross purposes. And so, you know, we focus on that as well in the book, the residence exclusion zones, which again, is another important feature of public policy here.

Josh Hoe

Strangely enough, one of the things we actually got rid of in the last SORN update here in Michigan, as a directly-impacted person, you know, when people asked me or when I’m speaking about this, I’ll usually say that the whole thing started, I’m sure that everybody had the best of intentions and were trying to be as logical as possible. And there may have been unintended, there definitely were unintended consequences. Wayne, I know your chapter kind of explains this. How did we get from where this all started to where we are today? Can you kind of give us a brief tour and maybe an understanding of the history of registration laws for people who don’t know who might be listening?

Wayne Logan

Sure, happy to do that. So, you know, historically, governments have tried to track individuals who have been convicted of crimes. So originally, of course, it was mutilation and bodily marking, photographs, when that came into technological wherewithal in the late 19th century. In the 1930s, in the United States, several localities in Southern California got the idea that they would require folks who were coming into town or living in town to register, and this was a broad realm of offenses. And they were mainly concerned about so-called gangsters infiltrating their towns because of increased access to transportation through trains and buses and whatnot, and kind of anonymously living in their midst. So the original laws, in the 1930s, were by local governments. And they were, again, very broad. They didn’t focus on sex offenders explicitly. In 1947, California had the first statewide law, and that law did focus on sex offenders. And it’s instructive to go back and look at the history of that law. When Governor Earl Warren was Governor of California, and there’s a lot of pushback, and a lot of people were concerned that, you know, we shouldn’t require people to register because they paid their debt to society, and they should be reintegrated and continue their lives. But that became law. And then slowly thereafter, in the late 40s 50s 60s, a couple of states had registration laws. A couple of them focused exclusively on sex offenders, some of them on people with drug offenses. But the laws really didn’t really have much interest and they weren’t really enforced very regularly or aggressively by police. Well, in 1989, a boy in the state of Washington was sexually assaulted and mutilated by a fellow who was just let out of prison and the police knew that this fellow was in the community. They were worried about him and when it became publicly known that the police knew about this fellow’s whereabouts and that he was the suspect for the victimization of this boy, people were very, very upset. They felt betrayed by their government. And they basically said, we have a right to know. So in Washington in 1990, they enacted a new registration law, but they also introduced something called Community Notification. And so for the first time, in 1990 information on registrants was made publicly available. At that point, it was a pretty modest amount of information and a modest slice of individuals who had been released from prison. But like a wildfire, over the next couple of years, every state gravitated to registration and unification laws, in significant part because the federal government threatened the states with a loss of Criminal Justice funding if they didn’t get registration laws, and then also community notification laws. So by the late 1990s, every state in the Union had registration and community notification laws. So it’s an interesting arc, how they came into existence, relatively modest state early on, and went into a period of lack of attention or use. And then really, just, as I said, like wildfire, things exploded in the 1990s. At the same time, actually, that very same law from Washington, Washington enacted a new generation commitment law, which entailed involuntary commitment, potentially indefinitely, of an individual convicted of sex offenses, the so-called sexually violent predator act. So that happened at that very same time in 1990, with that same legislation with community notification. So that’s kind of a back-of-the-envelope history. Hopefully, it’s helpful.

Josh Hoe

Do you have any knowledge on how people arrived at the particulars of these laws? Like the many requirements, was there data contributing to this? Or is this just like people’s best guess of how you get to a safer society through these laws? I’ve asked this question of sentencing experts before and I’d say did, was there any actual, you know, is sentencing literally just made up? You know, and most of the time they say, yes. So I wonder if you have any insight?

Wayne Logan

Well, this was and again, as I said, it remained so for many, many years until empiricists started looking at it critically. But yeah, the first law basically said, Hey, let’s rejuvenate registration, listen, adopt that. That makes sense. So the police can know where they are. But you know, we have a right to know, we have an informational entitlement, was basically where people were coming from in the state of Washington, they were outraged that the government had this information on this man. And they didn’t share it, let alone that he was led out in the community, right. So at the beginning, it was again, it was this visceral reaction to being betrayed, and that they had an entitlement to this information. And with that information, they will be able to take proactive measures to keep themselves and their family and loved ones safe. That was the basic idea. And that’s the model that, you know, continued on through the 1990s. And to this day, frankly. And, you know, one of the chapters in the books, …..at the University of Nebraska looks at you know, whether people look at websites these days, and those that do whether they actually take proactive measures, and there’s not a lot of strong evidence for either of those research questions.

Josh Hoe

JJ, most of the middle chapters are about costs and opportunity costs of registration. And I think Wayne mentioned a few minutes ago that a lot of this stuff is zero-sum. One potential opportunity cost, it seems apparent to me, that sex crimes are solved at very low rates, at least the data I’ve seen, and the registration at least uses a decent amount of law enforcement resources. If law enforcement is focused on people who are registered, and most new sex crimes are committed by first-time offenders, which is data I’ve seen as well, it seems to reason that this is potentially an opportunity cost. Is that fair?

JJ Prescott

I think so. I think one of the real downsides of the SORN legislation is it has really shifted everybody’s gaze to people who have been convicted of a sex offense at some prior point and has led policymakers to stop focusing on preventing first what you might call first-time offenders. And you’re right about the evidence, the evidence suggests, and Kelly Socia and others have looked at criminal records over time. And I mean, if you just look at who’s committing offenses, who’s being arrested for these offenses, who’s been convicted of these offenses, it’s on the order of 90 or above percent of people with no record of a prior offense, which means they would not be in or on a registry or being subjected to community notification. So, we spend a lot of time on these 10% of offenses, trying to figure out how to reduce them. And I think one of the things you realize is that even if this is like the most effective way of reducing recidivism ever, which we now know, it’s not, the real room for making a big difference is very small. I mean, you know, even if you reduce recidivism rates by 50%, you’d still have 19 out of 20 sex offenses occurring in this country, at least according to these criminal record studies. So I think we’re spending a lot of time focusing on people who have past convictions. And for whatever reason, that’s not where the action is, or where our focus ought to be.

Josh Hoe

Another of the kind of opportunity cost that’s mentioned by Kelly Socia, he said, another fiscal consideration is the impact of SORN on other potential strategies that might be effective in reducing sexual offending. “Every dollar spent retooling registry systems, purchasing hardware and software, or hiring personnel to maintain SORN systems is $1 that cannot be dedicated to substance abuse or mental health treatment, educational resources, parole and probation services or similar measures.” So it seems, even if you believed what you were just talking about if this was somehow a perfect recidivism kind of area or machine that it would also might ineffectively use resources within even that set. Is that fair?

JJ Prescott

Yeah, I mean, I think even if there were some evidence to suggest that these policies made a positive difference, an important question would be, well, how positive is it, relative to other programs that we could be pursuing? And I think the general consensus here is that these policies are quite expensive relative to most other potential solutions to recidivism.

Josh Hoe

Now, Jill Levenson also suggests another possible opportunity cost, she says, she talks about the cost of over-inclusive registries, which were, as she puts it, I know she’s a she because I’ve met her might actually interfere with law enforcement ability to monitor those at great risk to re-offend, and presuming strangers need to be protected against it, dilutes the public’s ability to identify truly dangerous individuals. Can either of you talk about this inefficiency in registration schemes?

Wayne Logan

Sure, I guess I’ll start the ball rolling. So I mean, one of the concerns about registration, of course, is that it creates a false sense of security. And JJ just alluded to that, because the majority of offenders are first-time offenders. So they’re not captured by the registry. So if you’re theoretically, if you are availing yourself with the information on the registry, you know, all you have to worry about is John Smith, two doors down. Well, you know, you’d be ill-advised to do that exclusively, right. Because, again, what we know about offending is that people will be the first-timers, right. And also, of course, it’s among familiars, particularly with children. And so it kind of in a way perversely discourages parents from taking more active roles in educating the children, trying to keep their children safe, because all they have to do is worry about John Smith, you know, down the street. And so, you know, the other issue, too, of course, is that, as I said earlier, they’re not availing themselves of the registry. So what are we left with? What’s happened over time, of course, initially, in Washington, it was very hands-on. So only the most serious registrants, level three, where the community was told about and it was done at community meetings, now it’s done by the internet. And, of course, which is indelible, even if the person somehow gets off the registry, whatever the jurisdiction might be, that information will continue on out there. But it almost is a band-aid where, you know, kind of going through the motions, and it’s kind of, you know, performative is one phrase that has been used. We have sworn here, we’re gonna put all these folks up on the registry. And we’re, we’re doing our part. And I think it’s kind of troubling that to the extent it’s an offloading by law enforcement to the public to kind of self-secure themselves. It’s not a very good method of doing that. We know that because folks don’t avail themselves of the registry. So there’s a whole cluster of issues here with respect to whether, you know, the scope of the registry is too broad, because, as one of the Supreme Court justices said in another context, you know when everything is classified, nothing is classified. And so if you’ve got a bloated registry, you know, not only do we have a problem with respect to ignoring the first offender, right, but we also have, if it’s undifferentiated in Florida, for instance, that’s basically everybody who’s a sex offender or a sexual violent predator, they’re on the list. They’re there indefinitely, a lifetime, right? And there’s no gradations with respect to any individualized risk. So what we’re expecting is hyper-vigilance from community members for the lifetime of these individuals on the internet. And that’s not realistic. It’s not realistic.

Josh Hoe

So another thing I think for many of us that Levenson’s argument raises is this notion that there could be a more effective registry or a safer register or a registry that produces public safety. I think a lot of us on my side of things tend to question that. And some of the things we’ve already discussed seem to suggest that while you might be able to tinker and make a registry a better registry, it doesn’t necessarily mean that you would produce public safety. Do you have thoughts on the policy end of what we should be looking for as an outcome, based on the data you all have read?

Wayne Logan

I’ll just say initially, then I’ll defer to JJ. For one thing, to have individualized risk assessments, they’re more expensive on the front end, because you have to dedicate the resources to evaluating people individually. As opposed to a one-size-fits-all, such as in Florida and many other states, right, where everybody’s on the registry, undifferentiated. One of the things that is happening lately, a very significant event we should mention here in our time together, is that the American Law Institute, which is kind of this august institution, they’ve been around for many, many decades. And they’re in charge of restatements of torts and contracts and property. But they also recently have overhauled the Model Penal Code. And they paid some attention to SORN in it. And very significantly, the membership said that we are going to no longer require committee notification, we’re only gonna have registration, and we’re going to have it for a much more circumscribed population. And so the registry will only be accessible by law enforcement, which is the way it was in the 1930s, up through 1990. So that’s a very significant development. And of course, it’s just an advisory body. But it’s a significant event because the American Law Institute is a major organization with respect to law and policy.

Josh Hoe

Yeah, in fact, you know, in several public discussions on this, I’ve actually supported a lot of the innovations that they suggested, but I think and, JJ, you might want to talk about this, too. Based on what we’ve seen, and I know, in at least one set of your data, what the answer probably is going to be to this – is it possible to have a registry scheme that is more likely than not to create public safety? I guess that is the best way I could put that.

JJ Prescott

I really think it’s a hypothetical. I mean, I don’t think we’ve seen such a system yet. But if somebody asks you straight up, is it possible to construct an effective registry? If you have infinite money and infinite focus on the right kinds of considerations? It seems to me that the answer has to be Yeah, like, I imagine there could be a set of people who have certain records who science and evidence suggests to us that they are likely to recidivate and at such a level that it would make sense at least to make sure law enforcement is aware of them and maybe even neighbors under certain circumstances. But to be honest, whether or not there’s a practical scheme, I’m pretty skeptical of something like that happening. So I mean, I think it’s theoretically possible. But there’s always going to be difficulties with classifying people, given the kinds of tools we have. And the type of registry, like I’m imagining would be so different and so much smaller in scale, that it would sort of be hard to describe it as the same type of tool that we see being deployed today. But I do think this is a hypothetical. And when somebody says something is possible, I tend to think well, you know, theoretically, it’s possible. But practically speaking, I think it would be extremely difficult for us to find the right balance to make what you’re describing happen.

Josh Hoe

I think both of you have mentioned the chapter by Lisa Sample, and her suggestion that while registration schemes are incredibly popular, practically almost nobody actually uses them, which sort of suggests that the costs are not balanced by the benefits, even if registries could be applied more effectively. What do you all think about this part of the data?

Wayne Logan

Well, it’s interesting because yeah, there’s a lot of results suggesting that people really, in the end, really don’t care that much if it quote-unquote, works, which kind of leaves us basically with, what do we have? It’s stigmatization and that’s okay because this subpopulation deserves to be stigmatized. But I think the next question, [and] you can’t obviously argue against that if someone feels that way, but the next question I think, [the] response needs to be well, let’s look at the data. Is this actually delivering public safety? And that’s kind of what started this conversation. That’s why we put together this book because we want people to look under the hood and think about this because again, there are trade-offs being made here, and not only can SORN be problematic in itself, but it’s coming at a cost of other interventions possibly.

JJ Prescott

And I’ll just say, I think there is an important set of psychological issues that have to do with the use of information as a tool, as a form of regulation. There, there was some work done years back by Molly Wilson, that talks about registries in general, not registries that focused on people who were convicted of sex offenses. And she comes at it from a psychological perspective and kind of ropes in thoughts that many of us have had about TSA. And this idea that if we know about something, for some reason, we feel like we’re more in control. And practically speaking, that’s a cognitive bias or behavioral bias, that oftentimes leads us in the wrong direction. And I think that’s really on display when it comes to SORN laws. Sometimes knowing things doesn’t make us any safer, and in fact, leads to all sorts of other negative consequences. And I think it’s really hard for people to imagine this idea that sometimes it would be better for everybody if certain things were not known than if certain information wasn’t out there. But that seems to be one of the drivers of registries that pretty much without any evidence, people naturally assume that if I know something, I’m aware of something, that I feel psychologically more comfortable with the situation when I’m facing risk because I feel like I can do something about it. And I think that may link back Josh, to what you were saying before about people liking registries, even though they don’t use them. And even if they go on to use them, they don’t use them in the way you would think somebody who was really nervous about becoming a victim [would use them]. Instead, it’s a source of gossip, or maybe even persecution of people on the list, but very few people actually change, or are engaging in what seems likely to be effective, protective, self-protective behavior. And that may make sense if we think that really what I love is that I can look somebody up, right, I know that it’s there in case I ever need it. And you know what, that makes me feel good. And I think a lot of times that that kind of that kind of behavioral drive is counterproductive both at the individual and the societal level.

Josh Hoe

And to speak to how that plays out. Your chapter with Amanda Agan JJ starts with a pretty strong summary paragraph, a coherent story emerges from this review, there is virtually no evidence that SORN laws reduce recidivism, or otherwise increase public safety. Can you unpack that a little bit?

JJ Prescott

I mean, there have now been dozens of researchers who like me, got interested in these new tools that began, you know, that have a long history, but really came back to the fore in the early 90s. And, and through state-level criminal records data or national level, federal criminal reporting data, many different strategies than all of which the hope has been when you’re going out when you’re testing something against the null to look for some effective these laws to identify some reduction either an overall frequency of sex offenses or in a reduction in recidivism. And really, there’s only one paper that we discuss in the chapter that has found anything reliably in the direction that maybe there’s some benefit here, and that’s an older paper by Do and Denae that that finds a very targeted notification regime in Minnesota, that looked at risk levels and applied to very few people that it may have had positive effects on reducing recidivism. But given how many papers have actually been written, how much data has been analyzed, it’s actually somewhat surprising that there aren’t more papers that randomly have found some positive outcomes that come from these laws. So I think that I mean, you really can’t find somebody who studies these laws, who focuses on this social problem, who believes that these laws are effective, at least notification, private registration. I think the consensus is very nearly the same. However, I think we know a lot less about how those systems might work just because there was just kind of a blip in time when we had them in the early 90s. And we went pretty quickly to a combined scheme where both law enforcement and the public were made aware of people who had past convictions.

Josh Hoe

And some people might say, okay, it might be true, the registration laws don’t prevent recidivism, but they probably serve as a deterrent. And I know you wrote about this a little bit in that article, is that the case? Or at least, is the deterrent impact significant enough to justify the human cost potential, criminogenic impacts, and opportunity costs of enforcement of the regime?

JJ Prescott

Yeah, great. So in my work with Jonah Rockoff, we do find that a notification regime, sort of a typical one, has some deterrent payoff. And I think that’s maybe not surprising, that the idea that you would be listed publicly and known publicly as a sex offender might cause you at the margin to behave differently. However, our research also shows that unless you’re at a really small scale, in other words, unless people are really deterred, and never actually commit crimes, that the trade-off doesn’t work out in favor of these laws, in other words, that any deterrence benefit is swamped in our research by recidivism-enhancing consequences that come from the criminogenic risk factors that are exacerbated by these laws. So pretty much every state, at the scale it operates now, any deterrence gains are completely swamped by recidivism increases that come from risk factors. Now, this, I think, is a broader problem that we have to think about when we’re thinking about punishment generally, which is, you know, one nice thing about really severe, terrible punishments is that they’re likely to deter. On the other hand, if they don’t really work well, you actually have to impose these incredibly costly and damaging punishments on people. And I think this is an example of that, even though there seems to be some modest improvement in terms of potential first-time offenders deciding not to commit these crimes. The consequences are that you have a lot of other people who, you know, commit these crimes, they’re not deterred. And then they’re made potentially more dangerous as a result of these laws. So hopefully that came across pretty clearly. But I don’t, I don’t think that notification can really be thought about as just a deterrent strategy, because in order to have it work as a deterrent strategy, it also brings along all of these risk factors for recidivism after the fact. And it’s really impossible to separate those two things.

Josh Hoe

And a little earlier, Wayne, you raised the ALI model statute. And I, for at least the last eight years, have argued for what I would have called presumptive graduation, over a period of time, kind of like the Clean Slate concept. If you stay clean for a certain amount of time you presumptively graduate. Because even if you believe that registries work, the more people registered, the harder it becomes to make the registry useful, which is something that JJ was just talking about in terms of deterrence as well. Do you have any thoughts about that or that part of the ALI?

Wayne Logan

Yeah, that’s an important feature, the new provision which says that people after a period of time, 10 years, can basically prove they’re fit, and if they don’t have any other offenses, they can be left off the registry. And that’s important. Many jurisdictions have some opportunity to get off or exit so to speak, but they can make it quite difficult. For individuals in Florida, it’s darn near impossible to get off. You know, one of the things we haven’t talked about yet, but I think it merits particular attention, is registration of juveniles, which a chapter in the book addresses, that Professor Letourneau of Johns Hopkins provides a wonderful chapter. And that, you know, really has remained a very controversial issue. So here we’re not talking about juvenile offenders who were prosecuted and convicted as adults. We’re talking about juveniles who are adjudicated, delinquent. And under federal law, and under many states, juveniles are required to register. And we’re talking about 14-year-olds, 15-year-olds, 16-year-olds, etc., and Professor Letourneau, I think quite nicely captures the difficulties that are presented in that particular sub-population, obviously a difficult phase of one’s life. And to be tarred early on indefinitely, very often, seems really counterproductive. And aside from perhaps being just improper, in principle, so that’s an important issue too. And I should say, I mentioned a moment ago when I kind of gave it a broad history, when the federal government came in and basically said, states, we need you to do registration and notification, one of the features recently was that we want you to register juveniles and many states said, No, we’re not doing that. And so they actually decided to say, well, we’ll do without the money, the federal grant money, because they were so principally opposed to it. So that’s another important aspect of this whole debate about how to deal with these youngsters who have been adjudicated delinquent with respect to sex offenses. But again, you know, many jurisdictions do allow it.

Josh Hoe

So, I think for most people in the general public, the way that they actually hear about the registry the most, and the reason, one of the reasons I think they think it’s effective, is because they see failure to register sweeps, they see stories about failure to register sweeps. But most of the evidence I’ve seen suggests that failure to register or failure to register correctly is rarely a marker for new crime. And so what people are seeing is people swept up essentially for what we would call in parole and probation, technical violations. Is that fair? JJ?

JJ Prescott

Yeah, that’s fair. I think that to stay in compliance is difficult, and burdensome, and people make mistakes. And although this is changing in a few places, mistakes often don’t protect you from being found guilty of a failure to register crime. I think the research on this suggests that failure to register is more an indicator of general, just a generally disorganized life. And so it doesn’t, it’s not linked, doesn’t seem to be linked according to the data to an increased proclivity to engaging in sex offenses. More generally, it seems to be that you’re more likely to fail to register again if you’ve failed to register in the past, and where there have been correlations between being convicted of a failure to register a crime, the correlation is to crime generally. So it’s a sign that somebody is in trouble socio-economically, they’re unemployed, they’re having trouble making ends meet, they have other issues going on, mental health or otherwise. And so failure to register is actually a general sign that they might need more help, not that they are engaged in sex offenses.

Wayne Logan

Related to that too, if I might add Joshua. So homelessness is a real problem for people who have been convicted of sex offenses. And it’s obviously aggravated when you’re on the registry. So there’s a rather significant homeless population. And of course, again, also, additionally, aggravated by residence exclusion laws, which place limits on where people can live. So JJ made mention of these kinds of disorganized lives. Well, for these folks where they have to list that, you know, I live behind the Shell station in the woods behind the dumpster, and they can be pushed away from that. And if they don’t inform the police of their new location, that’s an FTR. It’s a failure to register. So you know, again, it’s an issue of laws working at cross purposes. If we want these folks to be living lives that will be conducive to positive reentry, have stable housing and stable work, stable social relationships, and access to counseling and whatnot, we’re not acting in that way to achieve that result. And the failure to register data kind of reflects one aspect of that problem, particularly with respect to homeless individuals.

Josh Hoe

JJ, I know this is a little bit beyond the scope of any research that’s in this book, but I know I’ve talked to you before. There’s two things that have happened in Michigan that I think are interesting, and although it might be hard to study, they are probably worth studying. The first one is that because of a federal court judge, Michigan actually functionally didn’t have a registry for about a year. No one had to register. Well, actually over a year; and the second is that last year, we essentially got rid of the distance requirements and the school zones. And I know there’s other states that have that too. But we kind of are a before and after, I would assume, eventually. I was just wondering, I know you’ve said this would be very hard to research. But I’m wondering if you’ve had any other thoughts; the last time you explained to me why it was hard to research, even though I’ve had scope and methods and a few other things, my head spun for about three or four or five minutes. So I’m gonna try again, are there any hopes?

JJ Prescott

I actually think that the fact that the new SORN law in Michigan removes some of these residency restrictions and others, that’s a stark change required by a court, it’s unlikely to be correlated with other trends in sex offenses or other crimes. And it strikes me as a great natural experiment. I mean, it’d be even better if it happened at random times, and in other states, or was implemented in some way and it was rolled out at different times. But I think that there is sort of an obvious place to do some, some work and to look at how people who are either coming out of prison or coming off of a recent conviction, where they decide to live, where crimes that do occur, wind up being, relative to the places that used to be off-limits. And my guess is that we’re not going to see much of a change. And that’s going to be precisely because these residency restrictions didn’t accomplish very much given what we know about how people traveled to commit crimes and so on. But that, I think, would be the goal, the goal would be to show that really, there was no spike in crime or no change in crime. And that’s sometimes hard, because you ideally are looking for a rejection of the null to see some, some change here. And here, we’re actually looking for the opposite. We’re looking to show that removing a policy, really, that policy made no difference because nothing, nothing new is going on, people are behaving just as they were before. And I think that the one difference there is, or one, one way we could look for real improvement in the lives of people who were formerly bound by these things would be to look at how they disperse and change where they live, to make it easier for their kids to go to school. And so on. The other experiment where the registry was turned off for a year, a lot of that, from my perspective, depends on how people thought of or were aware of that treatment. So if it went from on to off, and people thought, and people were aware that the registry was no longer a thing, and it wasn’t available, you couldn’t find out whether people were on it before, as opposed to just not registering new people, then that too would be a nice experiment. But because it was off for a year, and I think that probably by the time people figured it out, it was mostly back on and functioning. It’s really unclear what we would learn from it, we might see as in the other situation, that nothing really changed, which is again, what we would hope to find. But in that case, I think somebody who wanted to criticize that claim would say, Well, yeah, this was a temporary thing, people probably didn’t realize it. And maybe if we really turned off the registry, we would see big changes in behavior. But when you just have a kind of a temporary short-lived blip, where everybody is really kind of unclear what’s happening, nobody felt comfortable to really shift their behavior. And so this doesn’t convince me. Again, not me, but the person who is critical of any research that shows nothing really changed during that time. You know, they might not be convinced.

Josh Hoe

I guess the thing that’s interesting to me is that the behavior of the people who check the registry, the registry wasn’t technically off. It’s just that the information was older. And so almost all the information people were gleaning from the registry was unreliable. And so if the notification scheme is supposed to be helping people navigate so that they reduce the risk to children, whatever, how could that be possible? I mean, like, I again, I don’t know how I would . . .

JJ Prescott

I think that, like what you’re suggesting, to me, just reminds me how much more we could do here if we collected better data, right? So right now at least, I’m unaware of careful measurement of how people are using the site. And you know, what they’re doing on the site and whether or not they are downloading, for example, during this period, outdated information or information that is still technically accurate if just because the person has continued to live in the same place and we just don’t know any of those things. And that’s a real shame, it’s really not that hard to capture this kind of information, storage is cheap, [there are] plenty of ways that it could be done. And the fact that law enforcement agencies tend to, I guess, miss the opportunity of collecting data that would allow them to show that their policies and their tools are making a big difference speaks volumes to me, it actually suggests, you know, what do you do when you’re not sure that your policies are working? Well, you know, you obfuscate, you make it. So it’s really hard to show that they’re not working. And so I think in all of these types of opportunities for study, so much depends on what data is available. And as you and I have discussed before, actually getting registry data over time, and identifying people who were sort of on the registry and joined at a certain time, all of that is basically impossible to do unless you have a court order. And, at least in my own experience, like I’ve had a lot of trouble in states like Michigan, and elsewhere, trying to get that. The one time I’ve ever had a history of where people have lived, that information happened to have been saved and stored by the state of Maryland. I used it to study like what, you know, where, where offenders who, who were listed on the registry moved and where sex offenses were occurring in that jurisdiction. And it turns out that, you know, it turns out that if you know, where a registered sex offender, a registrant lives, the risk of a crime a sex offense happening near that person is actually lower than it is in other places. In other words, there’s really nothing to the common sense, I guess, the assumption that if you’re closer to a registrant’s address, you’re at greater risk of a sex offense, that’s really what motivates a lot of what we’re doing here, or what the legislators are doing. And yet, it turns out to be like, factually untrue, at least in Maryland, so.

Josh Hoe

So you both helped edit and put together this book. What would you do if someone is going to, what’s the pitch you would give to someone who wanted to read this book? And then each of you, if you could say, where you think this is all potentially heading, what you think the next frontier of the fight is? Or you know, what’s the next thing that’s likely to happen as a result of the kind of data that’s come together about sex offense registries, etc? And if you would start Wayne?

Wayne Logan

Sure. Well, again, I kind of go back to where the ALI American Law Institute is on this. I mean, that’s a big shift from a major organization. And there are a lot of folks who, you know, advocates who say, we should just, both things should be blown up, right? Nothing at all. But I don’t think that’s realistic at this point. And, yeah, I approached this not as an advocate, I look at it really from a social science perspective. And that was the main purpose of our book. And so our hope here is we’ll put this information out again, that people make decisions about accordingly. And, you know, we don’t take a particular stance in the book, what we try to do is to provide the information that we talked about. So I think that’s the next stage really, is to try to look at the laws critically and perhaps modify them. Again, I tend to be pretty realistic about this or pessimistic, I guess, depending on perspective, that I don’t think these, I don’t think SORN laws altogether are gonna go away anytime soon. But I hope, with you know, consultation with the research, that changes will be made to make them better. And I think the ALI, the American Law Institute’s suggestions are a really concrete step in that direction, which is to say, limit the number of people on the registry, and to have it be private, so to speak. In other words, only accessible by law enforcement,

Josh Hoe

I still go with that graduation, to me, is kind of the grail of we might not be able to get rid of registries. But if we can get [to] where everybody can theoretically get off of registries, and you know, in a presumptive manner, I think that ultimately gets us close to the same thing. JJ, did you have thoughts?

JJ Prescott

I think one of the really great things about the book is that it tries to help somebody who’s new to this topic, maybe a judge, maybe an advocate, understand what to many, seems unexpected, that these laws really don’t seem to have the effects that a typical person might think they would and then to understand maybe the underlying mechanism. So for example, we have Lisa Sample’s chapter that explains well, in order for these things to work, especially notification, you actually have to have people going and using them in a particular way. And if it turns out, they’re not doing that, then it’s not surprising that these things aren’t making the kind of difference that a lot of people assume they will. And in fact, I would say that one of the most notable things about SORN laws is they’re very fragile in the sense that they have to have a lot of things go right in order for them to make the kind of impact that their proponents recommend. And this book helps, I think, people understand that from the existing social science. And in terms of where to go next. I mean, I’m just going to make a push, which I probably do in almost every talk I give on this, for more data. I mean, I think if we’re really serious about making the kinds of targeted changes, we really need to know where there’s a possibility of there being a positive role for these laws and where that’s just not likely. And in order to do that we need to actually dig into how these laws are working with particular subpopulations and so on. And that’s a real question, those are questions that are going to be hard to get at, without the kind of data that I think we could collect, but we’re not collecting, or at least it’s not publicly available right now.

Josh Hoe

We were talking earlier about well, Wayne was talking about being a little bit more pessimistic. I tend to be a little pessimistic myself a lot of the time. My friend – taking off your professor hats it doesn’t even have to be about SORNA – but my friend Amanda Alexander always talks about the power of dreaming big and having freedom dreams. So this season, I’m asking folks what dreams they have about changing our system. Outside of the work you’re doing, in general, if you have any dreams you could share with us, or any thoughts you could share with us in this area?

Wayne Logan

Sure. So one of the areas I also research and write about is policing. And of course, it’s a big, big issue these days in the wake of George Floyd. And, of course, you know, ‘defund the police’ has been a mantra. But I think people are kind of now reorienting themselves to maybe unpacking the police function. And I’m very optimistic about that. I think that’s a very good development. So for instance, people with mental illness, different autistic disorders, and things like that, the police are not equipped to work with those folks when they encounter them in the community. And unfortunately, tragically, a lot of times fatalities spin out of that. So I think one positive development now is kind of again, disaggregating the police function and saying, Well, maybe officers shouldn’t respond first, or perhaps people with background and training with mental health should be there with the officers. And so when I teach students, I always say this is a pretty great time to be interested in policy with respect to the criminal justice system, because not only are we looking at Mass Incarceration and policing the big issues, but people are really getting in the weeds and kind of looking critically at different components about whether they can work better. And then the corrections context is, you know, I’m sure a lot of the interest has been from the conservatives, the right on crime group. And of course, their orientation is more they want to, they don’t think it’s efficient use of tax dollars, etc. Whereas progressives are concerned about what they see as the inhumanity and the unfairness of the system. But those two forces coming together, we’re looking at the criminal justice system differently. And we’re starting to see slow tapering down with respect to incarceration rates. So I think it’s a propitious and optimistic time in which we live. And we’ll see if some of these things come to full fruition, but I’m optimistic generally, although I tend to be realistic that reform can be very slow and painstaking. And particularly with SORNA. As I said at the outset, there’s just a really strong emotive aspect to it, that it’s hard for people to focus on the data, even if the data is available. And with this book, again, we’re trying to make the data available, so at least they can have an informed decision about whether it’s the right public policy route to pursue.

JJ Prescott

Yeah, as a social scientist, I guess I love the idea of a freedom dream. And it sounds a little weird to say more data as my freedom, my freedom, dream, but I . . .

Josh Hoe

I think you have to admire your consistency. JJ.

JJ Prescott

I’m just gonna say that I think we do way too much on the basis of assumptions, and I think that actually, we’d be a much safer and freer society, if we spent a lot more time with data, and also recognizing that there are going to be times where the data don’t tell us the answer to a certain point and that if we had a sort of a presumption in, in favor of freedom in those circumstances. In other words, like if we’re going to be, I mean, this is, we teach in the first week or two of criminal law, that if you’re actually going to bring the power of the state, whether in terms of incarceration or execution or even putting somebody’s name on our registry, that you ought to have a burden of proving that it’s actually a good idea. Not just that the person is guilty of a crime, but how we actually move forward. Makes sense. And I think that we used to have a lot of trouble doing that, because we would just be on the one hand, on the other hand, anecdotal stories, how can you think about a burden of proof in that setting, when you’re evaluating policies? Well, you know what? We now have the ability to do that in a much more serious way, we can actually say, if we’re going to use these kinds of punishments, or these sorts of treatments before we do it, we ought to study it. And we ought to have an expectation that, at least, again, it’s hard to study policies that are not implemented. But there’s oftentimes going to be adjacent policies where we can say, Listen, we actually have really good reason to think that this will make a positive difference in society. And, and without that, I think there should be a pretty strong assumption that we don’t move forward. And if people started thinking about criminal justice policy that way, I think we would tend to have a lot less of it. And we would use a lot of other social tools, you know, family and religion and other institutions to help guide people to better lives.

Josh Hoe

I know we’re here to talk about your book. But I also like to ask people if there are any criminal justice-related books that they like and might recommend to our listeners. Does either of you have any favorite books?

Wayne Logan

Well, I try to do as much fiction reading as I can in the summer. So one book which I read recently, which I really enjoyed, was Nickel Boys by Colson Whitehead. The story basically concerns a kind of a reform school for delinquent boys northwest of here in Tallahassee, Florida, which existed for many years. And just tragically, so it was very poorly, inhumanely run. And they’ve only recently over the last 15 years found bodies buried there. And so they’re trying to unravel that story. But Whitehead’s book is wonderful, I highly recommend it. It’s called Nickel Boys. It’s a great kind of historical fiction account of the Dozier School here in Northwest Florida.

JJ Prescott

I’m gonna start off by pitching Wayne’s 2009 book, Knowledge As Power, which I think was, you know, what I would direct people to read if they really want to get into the idea of using registries in general. I think it was important to me when I started working in this area, and I think it’s a nice complement to what we’ve done in the other book. I mean, I’ve read other books, and one is not not too recent, but John Pfaff’s Locked In. It’s a database, not a database, but a data-based argument that really, I think does a great job at trying to figure out where mass incarceration comes from, and what are essentially the ambits of power of prosecutors, and where their voters come from and where the resources come from. And how do we wind up with a system that seems to be incarcerating far too many people? And what I love about the book is that it’s specific, it’s precise, and it leans on data to make its claim. And I think it’s also the kind of book that a lot of people can read,

Josh Hoe

I find it surprising that you appreciate it another economist’s book. I mean, in fairness, John was my 50th guest, when that book came out, well a little after that book came out, and actually someone I’ve gotten to spend some time with. So I appreciate that one quite a bit. Were there other ones? Or was that?

Josh Hoe

Those are good books. So how would you recommend people find your book or your book?

Wayne Logan

Well, I think it’s on Amazon. And I can hold up a picture. I don’t know if you have a picture there handy to you, Josh, or I can put it up here.

Joshua Hoe

You can put it up there if you want. People who are on the podcast will see it in the show notes.

Wayne Logan

So it’s on Amazon. It’s also published by Cambridge University Press. So it’s also on their website as well.

JJ Prescott

Gosh, I didn’t even think that it might be tough to find our book, but maybe it is. I don’t know.

Josh Hoe

Luckily, I got to read through a PDF copy.

So I always ask the same last question. What did I mess up, what question should I have asked but did not? Otherwise known as the humility question,

Wayne Logan

You did a great job.

JJ Prescott

I think you did a great job. I think one question I thought we might not get to but we did in a sort of roundabout way is just the question of reform versus abolition, whether or not we should go all the way. And I think we’ve had that conversation. I think that is a space where a lot of people are having conversations right now. And I think ALI’s, salvo here is, I think, going to raise a lot of those questions, but I think we did talk about that. So I think you did a great job.

Josh Hoe

Thank you. Yeah, I try to get a little bit or at least get an idea of what people’s response will be to questions like that through some of the questions I asked.

Well, it’s really great to have both of you on and I really enjoyed the book; I obviously had a personal stake in reading it, but I enjoyed it quite a bit. And thanks for coming on the podcast.

Pleasure, thank you very much. Take care.

Josh Hoe

And now my take. I don’t do many episodes about the registry, because I don’t want this podcast to primarily be about issues that impact me directly. But I don’t want to act like that makes this Kafka-esque regime okay.

Registries do not make our community safer. They do not help ensure that people do not commit new crimes or protect victims, they make our communities more dangerous, then make the people subject to them isolated, lonely, desperate, and give them no hope for a life where they can return to society safely. You may not like hearing that, but it’s the truth. Literally, mountains of evidence back up what I’m saying. Registries do not prevent new crimes, they do not deter. And the vast majority of people who commit new sex offenses are not on registries. Registries waste law enforcement resources that can be used to investigate and prosecute new sex crimes. And most new sex crimes are never prosecuted. Finally, even if you refuse to believe what I’m saying, despite the mountains of evidence, if you are so committed to punishment over reason that you will ignore all of this, you should support presumptive graduation from registries. Because if they are effective, the more of the registry is packed, the less effective it is at creating public safety. And if you reject all of this, you are in essence suggesting that you would rather create the situations likely to allow more sex crimes, make your communities less safe, and make law enforcement less effective at prosecuting actual sex crimes. Because that’s actually exactly what registration accomplishes. People who care about the safety of their community should actively oppose registries.

As always, you can find the show notes and/or leave us a comment at DecarcerationNation.com.

If you want to support the podcast directly, you can do so at patreon.com/decarcerationnation; all proceeds will go to sponsoring our volunteers and supporting the podcast directly. For those of you who prefer to make a one-time donation, you can now go to our website and make your donation there. Thanks to all of you who have joined us from Patreon or made a donation.

You can also support us in non-monetary ways by leaving a five-star review on iTunes or by adding us on Stitcher, Spotify, or your favorite podcast app. Please be sure to add us on Instagram, Facebook, and Twitter and share our posts across your network.

Special thanks to Andrew Stein who does the podcast editing and post-production for me; to Ann Espo, who’s helping out with transcript editing and graphics for our website and Twitter; and to Alex Mayo, who helps with our website.

Also, thanks to my employer, Safe & Just Michigan, for helping to support the DecarcerationNation podcast.

Thanks so much for listening; see you next time.

Decarceration Nation is a podcast about radically re-imagining America’s criminal justice system. If you enjoy the podcast we hope you will subscribe and leave a rating or review on iTunes. We will try to answer all honest questions or comments that are left on this site. We hope fans will help support Decarceration Nation by supporting us on Patreon.