Joshua B. Hoe interviews Kristin Henning about her book “The Rage of Innocence: How America Criminalizes Black Youth.

Full Episode

My Guest – Kristin Henning

KRISTIN HENNING has been representing children accused of a crime in Washington, DC for more than twenty-five years and is a nationally recognized trainer and consultant on the intersection of race, adolescence, and policing. Henning was previously the Lead Attorney of the Juvenile Unit at the D.C. Public Defender Service and now serves as the Blume Professor of Law and Director of the Juvenile Justice Clinic and Initiative at Georgetown Law. and she is the author of the book The Rage of Innocence: How America Criminalizes Black Youth

Watch the Interview on YouTube

You can watch Episode 129 of the Decarceration Nation Podcast on our YouTube Channel.

Notes From Episode 129 Kristin Henning – The Rage of Innocence

The books that Kristin recommended were:

Paul Butler “Chokehold: Policing Black Men”

James Forman Jr. “Locking Up Our Own: Crime and Punishment in Black America”

Full Transcript

Joshua Hoe

Hello and welcome to Episode 129 of the Decarceration Nation podcast, a podcast about radically reimagining America’s criminal justice system.

I’m Josh Hoe, and among other things, I’m formerly incarcerated; a freelance writer; a criminal justice reform advocate; a policy analyst; and the author of the book Writing Your Own Best Story: Addiction and Living Hope.

Today’s episode is my interview with Kristin Henning about her book, The Rage of Innocence, How America Criminalizes Black Youth.

Josh Hoe

Kristin Henning has been representing children accused of a crime in Washington DC for more than 25 years and is a nationally recognized trainer and consultant on the intersection of race, adolescence, and policing. Henning was previously the lead attorney of the juvenile unit at the DC Public Defender Service and now serves as the Blum Professor of Law and Director of the Juvenile Justice Clinic and Initiative at Georgetown Law. She’s also the author of the book, The Rage of Innocence, How America Criminalizes Black Youth, which she is here to discuss with me today. Welcome to the Decarceration Nation podcast, Kristin Henning.

Kristin Henning

Thank you so much, Josh, I appreciate it.

Josh Hoe

I would be remiss in not saying that it is really extra special to have you here now. Because we’ve actually had to make a couple of runs of this because of internet problems and stuff like that. But we’ll try to make the best of it anyway. And I really appreciate you taking the time. I always ask the same first question. How did you get from wherever you started in life to where you are a public defender for over 25 years and writing books about the criminalization of black youth?

Kristin Henning

Well, I think it starts with the fact that I came from a family that really cared about social justice, and about young people. My mother made her career in early childhood education. And my father, although he was a businessman, he also worked with young people in our church. He would have the young boys from the neighborhood over on Friday nights, you know, to talk about life. And so I think that’s a lot of it. I came from a family of teachers and preachers, but my real aha moment came during my freshman year of college; I had an apprenticeship at the local courthouse in juvenile court. And I will never forget the day, the first day of that internship, I walked into the courthouse, walked down the hall, and saw a line of children chained together at their legs and at their arms. And I just was shocked that we shackle children in contemporary America. And of course, most of those children were predominantly, disproportionately I should say, black and brown. And that was just, it really stopped me in my tracks. And when I entered the courthouse and met the prosecutor assigned to juvenile court, I said to her, I really want to be over there. And I pointed across the room to the defense table, and I said, I want to be sitting with the kids. She said, sure. You know, one day, you know, I’ll introduce you to the defenders. But that was my aha moment.

Josh Hoe

Since you have a public defense background, maybe a good place to start is discussing the recent attack that’s been going on on the idea of public defense. I think, you know, it was most heard during the recent confirmation hearings for Ketanji Brown Jackson. Do you have any thoughts about this idea that even the idea of defending people is problematic?

Kristin Henning

Yeah. I mean, this notion that somehow Judge now Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson was somehow at fault for defending someone of any type of offense, but the go to attack is usually around sexual offenses, right? As if anyone in this country should go without a defense, right? When everyone is entitled to a presumption of innocence at the front end, and due process, a meaningful opportunity to be heard, and to test evidence against them. And so that’s really, you know, fundamental to what we believe, it’s the entire framework upon which our justice system, our legal system was built. And so to question that in any way is extraordinarily problematic and we want to bring down the weight of the state through the police department and the prosecutors who have inordinate amounts of money to devote to this enterprise. And yet, you know, the notion that somehow it would be wrong to have ever been defending someone who’s accused is so extraordinarily problematic,

Josh Hoe

And as a person of color, who is a law professor, and has been involved in a lot of work around these kinds of areas for a long time,

do you have any other thoughts about those hearings a few months ago or a few weeks ago, and the process?

Kristin Henning

Oh, just that the, you know, I, it’s disappointing in so many ways to watch the politicization of this institution, and the ways in which it has I, in quite a naive way, as I was starting off my legal career as a young lawyer, and you know, really, for quite some time, honestly, maybe I was disabused only recently with the confirmation hearings, but just buying into the notion that the United States Supreme Court was the neutral arbiter. Right. And I, you know, I wanted so deeply to believe that. And if that one pivotal institution is no longer a neutral body, then what does the rest of justice look like? Right, Justice seems to now turn on – certainly, I’ve always felt that at the state and local level, that Justice turns on what we say, who you get, what Judge you get, what prosecutor you get, what defense attorney you get, undermining in every way, the rule of law, and there’s no safety or security, that you will have a fair and equitable opportunity to defend oneself in these moments. And now to think about even the highest court of the land, really turning on who you get in a particular season, in which these pivotal cases are being decided, really is frightening.

Josh Hoe

Yeah, you know, for some reason or another, when I was younger, I came into contact with enough postmodernism to always be innately suspicious of the ideas of neutrality and objectivity. And so I’m not sure I was there about them being you know, neutral, per se, I think people bring themselves to everything they do – is the way I would probably talk about it. And before we get to the book, since we’re talking about the Supreme Court, obviously, this is a very tough week, the last week and a half since the leak of the Alito decision, for lack of a better term, the trial balloon about Roe versus Wade, is there anything you would like to say about that before we dive into your book?

Kristin Henning

I mean, there’s just so much to say, even putting aside the content, right, like the ways in which we can undo, you know, individual rights of women – putting even that aside – just the tying it to this notion of the politicization of the courts is that we as a country can’t move forward with consistency and reliability, about fundamental rights when we have a decision that it’s so deep in our legal system to get upturned in an instant, based upon some recent, Judicial Justice appointment to that court, I think is also frightening. I am not one who believes that never ever, ever, you know, should we ever,overturn precedent, we had to overturn precedent in some significant ways with Brown versus Board of Education, and, the internment camps, you know, there have been moments, but this isn’t that moment, isn’t that moment, it’s not of that caliber. It’s an undoing of rights, fundamental right to privacy in ways that were very political.

Josh Hoe

And also, it seems to me, like I heard someone say something that I thought was a fairly interesting idea, which is this notion that someone could exercise a right one week, and be put in prison for using that same power a week later.

Kristin Henning

A week later, isn’t that amazing? It’s absolutely a powerful statement, and astute for this moment. And that goes to my notions of consistency and reliability. One can’t, you know, make decisions about one’s life, you know, with that type of upheaval, with the stroke of a pen, and it’s more than the stroke of a pen, right, with the appointment of certain justices to a court. And that, to me is what is terrifying, the fundamental premise upon which we can undo years-long precedent is now ….. And I think that’s what’s frightening.

Josh Hoe

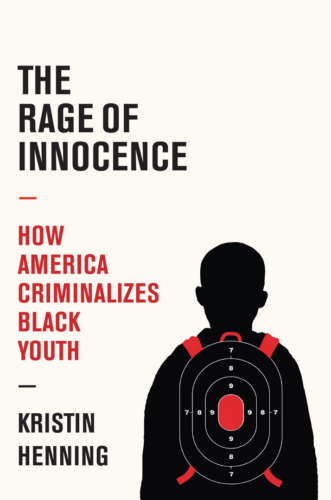

So you wrote the book, the Rage of Innocence, How America Criminalizes Black Youth, which is powerful, but also really hard to read in a lot of ways. Before we get into specifics I did want to ask one question. It seems to me that you can draw a line from the cover of the book back to Public Enemy’s iconography. Was that purposeful at all? Or just kind of happen that way?

Kristin Henning

No, yeah, probably just happened that way though I do write about you know, you know, hip hop and, and music. I don’t think I take on Public Enemy, though I love Public Enemy and, and talk about them often.

Josh Hoe

One of the biggest one of my Twitter moments ever was when Chuck D followed me.

Kristin Henning

That said, though, no, I think the cover was indeed very intentional. But very much so about the ways in which black youth are targeted. And, and it’s got, you know, the, as you can see, both in your book shot behind your head and behind mine, that we’ve got, you know, a black child with a book bag with a target as if it were target practice on his back. And that particular instance was a little boy.

Josh Hoe

Of course, one of the most famous cases that everybody knows about was a kid who was arrested for stealing a book bag.

Kristin Henning

Oh, right. Kalief Browder.

Uh, yeah, so that wasn’t connected up, either. I love these. Now you’ve given me more to talk about on the road! And what the cover could mean.

Josh Hoe

I think that the reason why Public Enemy uses that iconography is very similar to the reason why you’re using it. So I think that maybe there’s a spiritual kinship there if nothing else.

Josh Hoe

So the thing that always gets me thinking about this topic, that thing that I can’t get my mind past, I mean, there’s a lot of things that upset me. But I think the thing that since it happened, I’ve never been able to get past is the case of Tamir Rice. My feeling is that we have been in an incredibly bad place in this country. If a young boy can’t play in a playground with a toy gun without getting shot dead within five seconds by police. I’ve unfortunately watched that video way too many times. And it’s still just, I can’t process it correctly. Can you use this example to kind of ground your work and what the book is about?

Kristin Henning

Yeah, that’s a wonderful question, because it allows me to sort of highlight some of the key themes of the book, all of which are, you know, evident in that story, starting with the criminalization of normal adolescence, and so you, you hit the nail on the head, I mean, the idea that a child of any race or class can’t play, right, is in and of itself, a huge revelation and problem for our country. And so I learned a lot in writing this book about the extraordinary developmental benefits of recreation, play and leisure. And it is something that I think I and so many of us take for granted, you think about these last two years, and how difficult it has been for all of us as adults in the pandemic, and the absolute need for just to be able to walk outside and breathe for a moment, of being able to relax and laugh, and whatever it is, you know, whether it’s watch TV, you know, even with a mask, you know, seeing friends, when the summer is going outside and having a picnic in the backyard, all of those were essential for our mental health as adults; think about how much more so that’s true for children. And so I began to realize and study about these developmental benefits. You know, play is not only essential for physical exercise and growth, but it is also essential for that mental reprieve. Life is stressful for all of us. And that play gives a child a chance to put life in perspective, to have the pressure off, and just enjoy. So that’s one thing. The other thing is, we know that play, recreation, and leisure also contribute to social dynamics, right? It teaches leadership skills and how to work well with others. And, you know, it teaches young people to figure out what they’re good at, whether it’s athletics or being creative and playful. So all these things are part and parcel of how we grew up to be good, healthy adults. And so we’re depriving black children in particular of these moments of this essential developmental stage of play recreation and leisure. And so that’s one thing.

Josh Hoe

It’s kind of interesting because I think on the one side, you kind of have this thing where – I think they call it the opposite of free-range kids or whatever where kids aren’t allowed to go out, be away from their parents, do any of the things that we did when we were probably kids. And then on the other side, you have this thing where kids are being seen as the problem. And so they’re not allowed to, it’s like a no-no; you wonder, where can kids be kids?

Kristin Henning 1536

That’s right. There’s no safe space. I mean, Tamir Rice was in a park, the quintessential place for play. I say all the time, you know, kids aren’t safe in school. Kids aren’t . . . to play and experiment in school anymore. Kids aren’t, it’s not safe for them to sit on their corner, right, in their stoop on their front porch in black and brown communities that are heavily policed. I write a lot in the book about other examples of play, right? Or just the whole recreation after school kids very often convene at a local restaurant, the local Rita’s Ice, the local McDonald’s, and they walk home to school, and they hang out in front of those places. And that – we see children after children, you know, being arrested in those spaces for – I had a child arrested for incommoding, like what in the world is incommoding?Turns out, it was blocking passage. So a fancy term for blocking passage, so that people couldn’t get in the front door; are you kidding me right now? You know, just ask the kid to move. So if a customer needs to go in those kinds [of settings].

Josh Hoe

We also have this other kind of facet of this, which is that often for, you know, reasons I’m sure you can expound on, black and brown kids are often one of the things you’ll hear after an incident like that, or Michael Brown, or any of the others is well, they will look too old for their age, they’re big for their age or something like that. Is that one of the issues too?

Kristin Henning

Yeah. So one of the second themes beyond this notion of play is the notion of bias, right? And the ways in which exactly you said, you know, so with Tamir Rice, the officers were interviewed, and they kept saying that Tamir looked older than his age, and they focused it on his size 36 pants and his extra large jacket and said, he’s five feet, how many ever inches tall. And as if they could not see this baby face, his 12-year-old baby face that we see in images. And so the speed with which they approach I mean, that he was shot in less than three seconds. And they did not allow themselves, you know, to register, to know him at all. But the point is, the research shows that even if they had, research shows that black children are perceived both by law enforcement and by civilians, to be significantly older than they actually are, more than four and a half years older than they actually are. So you think about a 12-year-old Tamir, he’s perceived to be 16, almost 17 years old, then, you know, think about a 16-year-old black youth perceived to be 20-21. So the complete adultification, and similar research has been done with black girls as well, finding that adults tend to perceive black girls as older, more mature, more knowledgeable about adult topics, more adult-like in the way they carry themselves, less innocent, and less in need of protection. And so the bias is significant, particularly as it relates to children. And I should just tell you one last study, really, really powerful study that fully demonstrates the purported cognitive association between blackness and criminality. There’s one study finding that people are more likely to misperceive a toy, a baby’s rattle as a gun, when it is held by a black face, a black face as young as five years old – and that’s a powerful association, right. So it’s really a profound impact on what’s happening with children.

Josh Hoe

So we’ve got this. So one part, we’ve got, you know, people who are terrified to have their kids be out or doing anything for a number of reasons. On the other hand, we’ve got the kind of criminalization of youth and then we’ve also got these – massively in the last decade or two decades – this growth of the surveillance state and you know, even because of school shootings, it’s even gone into shoot schools and so people grow up kind of constantly under suspicion, surveilled, harassed. This creates kind of a, for lack of a better term, a kind of a wound, an ongoing wound that you know you’re living through a kind of unfreedom in a way. Almost a kind of trauma. One of the first stories you share is the story of Shakara and Niya. Can you talk a little bit more about that?

So yeah, in that context, Shakara and Niya Kinney are children, two girls, black girls, at Spring Valley High School in South Carolina and Spring Valley itself. Or I believe it’s Spring Valley High School, maybe in Columbia, South Carolina. I’m misremembering, but the point here is one of the themes you talked about as surveillance, that hyper surveillance, and I think so many of us are so many, you know, folks, particularly, you know, in the middle class who grew up in schools without heavy police surveillance. And now, you know, black children walk into the front door, and automatically see, are greeted by a phalanx of police officers in uniform with weapons go through metal detectors and the light. And so here in Chicago story, so Chicago was, her team was in her math class and they were taking a test, and her math teacher saw her on her phone. Well, the math teacher reportedly went up there and said, you know, put your phone away. She didn’t do so immediately. And so he calls for assistance at the front office, and the front office sins. A school deputy comes to the classroom and literally physically rips Shakira from her seat, right in front of the entire class. Niya Kenny is relevant because she stops and records this incident. And that tap became a national story, because she recorded this encounter. And so again, more themes. One, you know, this notion of children being under the constant surveillance of police, that the over reliance on police for routine discipline of children, routine school discipline, also, you know, the use of excessive force, right, the violence both with Tamir Rice and with Shakara. Why is that a necessary response? Even if police intervention were necessary in those moments? Why do we default to tasers, dog bites, body slam procedures, like the one that was used to on Shakara? Guns! Why are we shooting? You know, children in the pretty long list of children who’ve been killed by the police in the last couple of years? Why are we resorting to any of that? As a response? It goes back to our earlier point, children aren’t safe, like children say, and if you want me to talk about trauma, we that’s a whole nother scenario; I have an entire chapter on trauma associated with police presence.

Josh Hoe

And you know, I think it’s also interesting that Niya got in trouble, for in essence, reversing the surveillance on the officers. So like, even, you know, in a sense, trying to use the same kind of surveillance to protect people can get into trouble.

Kristin Henning

That’s absolutely right. And we see that that’s very common, where the police officers consider it disrespectful, inappropriate, you know, and at times even criminal to be recording them. And so no doubt she actually got arrested. Niya Kenny was arrested. And she, because of her age, got charged as an adult, even though she’s a student in high school, right. And she got charged for disturbing schools, was one of her charges. And so other kids across the country get charged with interfering with a police officer for doing absolutely what is their right, and what’s pretty much essential to protect the rights and interest of children.

Josh Hoe

So many times you can’t go out, when you can go out, you’re probably being surveilled. You might be harassed, you might be thrown on the ground, you might this, that and the other. And you can’t even express yourself through the traditional means that most of us – I certainly did when I was a young kid. I used to be a punk rock kid and have crazy hair and wear you know, stuff like that. But that’s also not being allowed, in many cases, the actual wearing of clothes becomes the justification for arrest. I think, you know, for instance, that Geraldo said that Trayvon Martin’s hoodie was as responsible for his death as George Zimmerman and you have other stories about people who are criminalized for the kind of hair they have, or you know, the way they . . . do you want to talk a little bit more about that?

Kristin Henning

Absolutely. So again, one of the significant themes in the book is the criminalization of normal adolescent behavior. So I asked people to think about what did you care most about when you were a teenager, and people invariably talk about the clothes that I wore, the music that I listened to, the parties that I got invited to, you know, the friends that I had, those are the things that young people care a lot about. And so think about when much of that is penalized for black and brown children. So you talked about clothing, for example. And I think about the hippie era, right, with bell bottoms and tie-dyes. Nobody ever criminalized those clothes, even though they were associated with, you know, drugs, hallucinogens, and things of that nature. Think about the Goth era, where folks were wearing all black, young people wore all-black attire and straight, dark black hair. None of that was criminalized, even when that became associated with some mass shootings. And then think about the steel toed Doc Martins that people wear today, with red shoelaces, right, and profess to associate that with white supremacy in some way. Again, never out loud, never criminalized. Yet we see black children wearing sagging pants. No, I don’t want to see any kids underwear either. But is it a criminal offense? Should we be responding to that as if it’s a criminal offense that warrants arrest, prosecution, and detention? And that’s the disparity we receive. And mind you, it is absolutely a racial distinction. Because Justin Bieber, is known as a fashion icon, certainly a pop culture icon, and he has his pants sagging and talks about it with great pride how he has his pants sagging, and nobody would arrest him. And so that’s, you know, one example. Another really good example is music, right? And we think about country, heavy metal, rock, pop music, all of which has the same misogynistic, violent themes that at times glorified drugs and alcohol and other things that we don’t want our children to endorse. But those songs are popular and win awards without any consequence. And then you think about rap music and certain genres of hip hop. And those are demonized as if it’s the most dangerous music alive. And it says, somehow, you know, causing people to commit crimes, when it ignores so much of the beauty in that music and the pride in the political statements, positive political statements or that music. But my point here is the ways in which those normal features, important features of adolescence, are differentially treated for black children than for white children in ways that criminalize them.

Josh Hoe

And one of the examples that you give in the book is the Mystic Valley Regional Charter School. What they did with Maya and Deanna Cook.

Kristin Henning

So those are two black girls in Massachusetts, who were adopted by white parents, and during their self-exploration, as they were coming into their own identity, they began to learn more about their African American heritage, and one of the things they decided to do was to have braids added to their hair extensions. And these girls were told to remove their braids. And if they didn’t, they would be suspended, excluded from their extracurricular activities and suspended from school. And, again, we see that across the country that just normal features, that black hair has been criminalized. I mean, so much so that across the country the Crown Act has been adopted, which is a statutory prohibition on discrimination on the basis of hair, particularly hair associated with certain racial and ethnic groups. And the fact that we have to have some statutory piece that says that is so disturbing, and it’s as if . . and look, those were the girls, you know, that were criminalized, and they’re not alone. Black boys. People remember, Dre. They called him Dre. Dre was his nickname out of New Jersey, a wrestler who had his hair in dreadlocks, and the referee for the wrestling match insisted that he cut it off before he could continue with the wrestling match. And the argument was that the hair violated the rules saying that it was too long. And the reality is that white boys who had long hair were not told to cut their hair. So it was clearly a racialized statement. But these are such important pieces for black youth: hair, close friends, music, and we’re really depriving black children of the opportunity to be black kids, just to be kids.

Josh Hoe

I think when I hear not only white people, but a lot of white people talk about this, you know, it comes up as something about what’s been called respectability culture. I think that for a long time, Bill Cosby was associated with that. There’s some other people who have, and you heard a lot more of it coming out after the Will Smith episode at the Oscars, there’s also this notion that if people are showing identity in a certain way that somehow they’re not representing themselves correctly, and should be disciplined for that.

Kristin Henning

So this notion of respectability politics is internal, the ways in which even within the African American community, the elders, or, you know, certain parents, or more conservative voices within the black community, say to young people, that they should conform to mainstream society, and should not wear their hair in braids, or in dreadlocks or the like. And what we find, though, I think, is a really nuanced examination of what’s really happening on some level. I think these are also safety politics. In other words, black elders and black parents think that they can protect their children from harm, from getting shot, and from getting excluded from opportunities, like education, and employment, by dressing in their Sunday best and looking like, you know, traditional mainstream America. But here’s the problem with that. I think young people see for themselves that throughout history, including the civil rights era, that black folks who dressed in their Sunday best did not avoid discrimination and did not avoid violence. Right. And so, you know, they know that safety politics doesn’t work. Also, there’s a body of folks within the black community who profess this respectability politics, I think, in some ways, out of their own prejudices right out of their own complicity in some of this implicit racial bias, right. And what it is that dreadlocks mean, what it is that sagging pants mean, when they don’t mean that at all, right, that they are the precursor to violence into, you know, an unproductive life when we also know that that just simply is not true. And so I think it’s just such so much more of a complicated story, and that we have to figure out, why is it that we demonize certain adolescent culture, but we don’t demonize tie-dyes and, and, you know, baggy pants, I mean, a tie-dye and bell bottoms during the hippie era. And I think one of the other things that’s worth noting is all the ways in which black culture has been appropriated by mainstream media and white media. And, you know, by the artistic culture of America for their own economic gain, right, so that again, Justin Bieber wearing sagging pants is like a thing, right? among white kids. And there was a time when white kids, white girls would braid their hair to look like, you know, extensions as well. All of that is fine. It’s when it’s demonizing black kids, and so I think it’s really important that respectability politics misses the point in a lot of ways.

Josh Hoe

Yeah, there’s kind of a famous bit from the movie Do The Right Thing where Spike Lee’s character is talking with the guy he works with, who was pretty much a racist and he brings up that the guy, all of his favorite people . . . how can you act like that when everyone you like is a black performer, your favorite musician? You know, it’s a really good primer for this part of the discussion. Now, I know when I was a kid, if I did something wrong, I would get sent to the guidance counselor. I mean, I’m sure everybody has seen the movie, The Breakfast Club; you might get detention or you might get some kind of school service, but that’s not how schools operate anymore. I think you refer to entering schools as like entering prisons. Now, I know a little bit about entering prisons, but not so much about entering schools.

Kristin Henning

Yeah, so I mean, truly, when I go into a local school, the front door looks a whole lot like the front door of a detention facility. And so, for example, [school security] with a weapon at their side, they get wanded, their bags get searched. And it looks a whole lot like what it looks like to enter a detention facility. And, you know, school resource officers exist now in all 50 states. And I have to say, there’s a racialized history with that. I bought into, accepted, for the longest time, the often-repeated narrative that we have police in schools now, because parents and teachers were afraid to send their children to school after the mass shooting in Columbine in 1999. But as I did research for this book, I realized that the first police in schools appeared in Indianapolis in 1939, with the earliest conversation about even the possibility of integrating schools, then police in schools increased exponentially in the 1960s in the civil rights era under the guise of facilitating a safe passage for meaningful integration of schools. But we know from the iconic photograph and the historical record, that very often or far too often police presence was an impediment to meaningful integration to schools. Fast forward to 1991. We now had by then, so many police in schools that the National Association of School Resource Officers was founded with national conferences and a mission statement and the like. Fast forward again to 1994, still six years or five years before the mass shooting at Columbine, and we have the federal cops in schools framework created, which was the framework that allowed the federal government to funnel in money to states and eventually to localities that would hire school resource officers, right? And what’s happening in the mid-1990s? The superpredator myth is alive, right? That is explicitly targeting black children. And the myth was that black children would run amok and rape, maim and kill much of America if we didn’t do something to intervene. And so even after that myth was disproven, and even after Princeton professor John DiIulio recanted that myth, the narrative that grew out of that still lives on in the American psyche, such that, you know, teachers and school counselors are afraid of children, of black children in particular. And so that accounts for in many ways why it is that schools look like prisons or detention facilities in so many ways.

Josh Hoe

So often, when we talk about public safety, we talk as if it works the same for every person and family in every place. In other words, we rarely ask questions about who is being kept safe? By the things that we do. You talk a lot in the book about families who are afraid to even call the police or your clients who are conflicted about calling for help, even when people they cared about were in danger. We’ve got all these things, we’re saying kids can’t be kids, they can’t do this, they can’t do that, they can’t do the other, they can’t have hair, they can’t wear clothes, they can’t listen to music, they can’t even be free in their school rooms. And on top of that, they’ve been – depending on where they lived – harassed every single day to the point where the faith in the whole idea of the police comes into question in their head. You have a chapter called policing as trauma. Can you talk more about this?

Kristin Henning

Absolutely. I was so moved by what I see my clients experience. And I opened that chapter with a story of my client, I call Kevin, and I was sitting in my very office that I’m in now. And we get a phone call from that client saying, Is there a warrant for my arrest? And we thought the question was really odd because we had actually just been to court with that client the day before, and had there been a warrant certainly the police would have, you know, taken him that day. And so we asked more questions, and we could hear his mother in the background yelling boy, you’re just being paranoid. No police officer is out there waiting for you. turns out that he had been sitting in his window for

two hours and he could see a police car parked out front. And he was convinced that the police were waiting to arrest him the second he walked out. And you know, for somebody, any of you listening, who doesn’t really understand what it is like to grow up in Kevin’s neighborhood, you might be thinking, Well, if he hadn’t done anything wrong, or if he’s not doing anything worthy of being arrested, then he shouldn’t be worried. But what we don’t realize is that Kevin has lived in a neighborhood where he’s been stopped more than 50 times.In his very young teenage life, for doing nothing at all, you know, he gets stopped on his way into the convenience store on the way out, gets stopped and searched while he’s sitting in a folding chair with his friends in front of his apartment complex. And so, you know, having done one crime in the past, having used drugs as a teenager doesn’t then thereby give police the right to stop you all day. So what I realized when his mom said, Boy, you’re just being paranoid, I was like, you know, he’s not paranoid. He’s just traumatized. And so I began to do the research on trauma. And what I found was, there’s a growing body of research, documenting the extraordinary psychological trauma that black and Latino children in particular experience in contact with the police, especially during those adolescent years. The research shows that black and Latino children who live in heavily surveilled neighborhoods, or who are the target of significant stops and frisk, report high rates of fear, anxiety, depression, helplessness, they become hyper-vigilant, meaning that they’re always on guard, and not trusting others, and in particular, not trusting police officers. And that distrust of police officers carries over to other adult figures, like teachers and counselors. And the research is also powerful because it shows that the trauma occurs not just from being the direct target of that police contact, but also from witnessing it or hearing about it among friends and family. And so it’s really much more devastating than I think most people realize. I will have officers say to me, Oh, I just stopped and asked him questions. You know, I didn’t you know, frisk him, I didn’t touch his physical body, not realizing that even that stuff, even that kind of questioning is in and of itself traumatic. And most of us take it for granted that we can walk through our own neighborhoods, right, and not be subjected to undue intrusion by the police. But that is just simply not for so many black and brown children in certain pockets of our country.

Josh Hoe

And to just go back to the cover of the book, you know, I mean, if you look at the cover of the book, you know, the way the perspective is, you are thinking from outside, look at that kid who is a target. But if you reverse it and think about the kid always being the target, it’s a whole different thing. And I think you share the story of a 14-year-old, you know, when people are saying, well, they must have done something, they must have done something, you share the story of a 14-year-old Tremaine McMillan, who the police accused of making dehumanizing stares, you know, I mean, the pretexts that people use for the stops. You know, as frustrating as the rest of this, do you want to talk about that a little bit?

Kristin Henning

Absolutely. I mean, and again, this ties back to the criminalization of normal adolescence and our perspective on and perception of a black child. I mean, Tremaine McMillan was like a child at the beach on Fourth of July, you know, in Florida, and he was roughhousing, literally tussling on a beach like two children do. He and another friend of his who were at the beach together, just tussling and having a good time, play fighting, and a police officer comes up on his ATV and it’s like, where’s your mother? You know, you need to leave, and literally like any child would do. They’re like, for what? What did I do? And the officer claimed that he was quote, unquote, making dehumanizing stares and balling up his fist. Well, I don’t know about any of you out there. But have you seen a kid who thinks something is unfair? They huff and they puff. Right? And they’re emotional and they’re reactive. They do what teenagers do. That’s what they do. And but he got, you know, literally arrested, taken to the ground, put in a chokehold and you know, Tremaine was holding a little puppy, and his puppy you know, gets you know, smashed up under the takedown. I mean, it’s just appalling. And their reaction, the officer’s reaction in subsequent news interviews like it is in so many places across the country, well, if he just obeyed, if he had just complied. Wait, I’m sorry, what part of he was a teenager did you forget, right?

Josh Hoe

Like, it’s also like, not like he wasn’t complying. He just wasn’t happy about it.

Kristin Henning

Exactly.

Josh Hoe

I get in a lot of trouble sometimes, because everybody loves the character, Batman. You talk about this a little bit in the book, too. I personally have never been a fan of Batman, not that the storytelling is bad, or the movies are bad. But it seems to me like it’s propaganda. It’s an attempt to normalize “tough on crime” narratives, vigilantism, and justify that kind of violence. We just had like the 20th, retelling and a movie of that story. But I feel like this plays out generally a lot more like what happened to Jordan Davis, and you’ve put this all in context.

Kristin Henning

Jordan Davis is playing loud music, right? Like, that’s the narrative there. And the ways in terms of vigilantism, right? That the ways in which we as a society have demonized black children for their normal adolescent behavior is not just police officers in a blue uniform, but also civilians, right. And so he’s, you know, literally at a gas station in a car with some friends. I want to say that was over Thanksgiving weekend, right? Or, you know, the Thanksgiving holiday. And, you know, his friend is playing his music too loud in the car in which they’re riding and not too loud, playing it loud. A gentleman comes up, parked next to them in a gas station, mind you, he’s from out of town, but he comes and he parked next to them. And he says to them, can you roll down your music? Right? And one of the people in the car says, okay, turns down the music. Jordan Davis, again, being a teenager says In response, well, no, we don’t have any obligation to turn our music down. And you know, he turns it back up. And next thing you know, the white gentleman gets out of his car, and proceeds to shoot into the car and kills Jordan Davis for playing his music. It’s that kind of vigilanteism, that is terrifying on every layer imaginable. And one of the things that I sort of draw an analogy to in the book is the ways in which police officers in a blue uniform, have perpetrated violence against the Tamir Rices, the Mike Browns, and repeatedly are exonerated or not held accountable. it sends a message right to the rest of civilian society, that indeed, black children must be, you know, dangerous and violent. And that it’s okay to defend yourself and protect yourself in these moments, not realizing the ways in which they manipulate these stories. I mean, there was Tamir Rice, 12 years old, absolutely nothing threatening about him playing with a toy gun. I’m Jordan Davis, same thing, you know, no, no, prior contact, no way to demonize him. His mother is actually now a congresswoman. And let me be clear, when I talk about these children not having any prior record, even if they did, doesn’t justify the type of intervention, violent and punitive interventions that we … for so many black children.

Josh Hoe

I appreciate that as someone with a record, I’d prefer [people] wouldn’t look at me as free or fair game simply because I was arrested many years ago.

Kristin Henning

Right? That’s right. Nobody’s as bad as the worst thing they’ve ever done. Right?

Josh Hoe

You talk about people being arrested, convicted, sometimes beaten, and even killed, by a stereotype in a sense. You could argue, in a way, another way you can look at the cover is that, you know, there’s a cutout of how everybody sees each person who’s black and brown, and they fit everyone to that kind of stereotype. In a sense, you could even argue maybe that’s one of the central theses of the book. Am I kind of getting that right?

Kristin Henning

I love it. I love it. You’re like my analytical hero here. No, but absolutely right. The ways in which and it goes to this implicit bias, right? Like the ways in which black children have been reduced to sort of this reductionist approach to black children, let’s all be the same, right? It’s the same thing with music, the assumption that all rap is the same, right? All hip-hop music is the same when in fact, even within rap music, there are multiple sorts of genres. In the same way, there are multiple genres within country music, there’s dirty country, but we tend to over essentialize you know, blackness and black children in particular, in ways that dehumanize them and criminalize all black children. And that’s in part the root of these racial disparities, both in the arrest, prosecution, detention and use of force against black children.

Josh Hoe

I think another question that, I don’t know if the book . . in a sense, the book asks this, I’m not sure if it answers it, but this is something I think about a lot is, What is equal justice? I’ve thought about this a lot, because I tend to think what we should be asking for is equal mercy instead of equal punishment. You know, a lot of times people say, there’s a lot of examples, we’ve gone through like this, you know, hippies didn’t get this criminalization. And people’s tendency is to say, let’s make everyone get the same punishment. I think Tom Cotton most famously said, Let’s not get rid of mandatory minimums, let’s just make sure that everybody gets harsh sentences. And my thinking is, if you do that, you’re just going to continue to ramp up the amount of punishment that everybody gets, that’s the way it tends to work. It’s like, you know, we just keep turning the dial-up. What I want is equal mercy, not equal punishment. But to some extent, that’s easy for me to say because I’m a white guy who did a very short sentence. I guess I just think that equal punishment tends to serve the same narratives and stereotypes that we’re trying to break down here. I suspect that you probably struggle with this a bit yourself. How do we find actual justice? What, where is actual justice?

Kristin Henning

Well, you know, it’s interesting, Josh, that it’s a little bit, in my view, easier to talk about what equity would look like when we’re talking about children in the legal system. Right. And that is, I would argue for a developmental equity framework, which is not a punitive framework at all, and that we as a country have decided to have separate juvenile courts for children who make mistakes and commit offenses, and that the philosophy

Josh Hoe

Of trying to make as few of them eligible for it as possible, but yes.

Kristin Henning

Right. Exactly. Yes, exactly. By transferring kids to adult court making exceptions to the juvenile court rule. But here’s the deal, right. But the juvenile court is alive and kicking, and that the fundamental philosophy behind juvenile court is a rehabilitative approach. It’s not meant to be punitive at all. And in the last, you know, quarter of a century, the last 25 years, we now know more about the adolescent brain than we ever did before, right and adolescent key features of what they call social, the social psychology of adolescents more than we ever did before. And that research leads us to two places: one, diminished culpability of children, right, so that the mitigating effects or the mitigating benefits if you will, of adolescents vote in favor of less harsh, less punitive senators. So our Supreme Court has declared that the death penalty, although we did it so incredibly late compared to other countries, but that the death penalty is inappropriate for a person who commits a crime under the age of 18. That even juvenile life without the possibility of parole is inappropriate for all people who commit crimes under the age of – non-homicide crimes – under the age of 18. And then even mandatory life without parole is cruel and unusual punishment, even in homicide cases for children, right. So there’s this notion that we know that children are less culpable for all the features. And guess what, they’re also more amenable to rehabilitation. I wanted to belabor that point to give you that detail because that’s the foundation of developmental equity. We have decided that as a country now, what the data shows is what you were getting to, which is that we make exceptions and the exceptions fall disproportionately on Black and Latino children. So when you get into these severe sentences, the more severe the sentence, the greater the racial disparity is. So you think about juvenile life without parole or the notion of life without parole for a child, right? As if they can never be salvaged as if they can never be redeemed, which just the science just does not support that proposition. When people make that decision. They’re talking about black and brown. And then the final point I’ll make is somebody did an empirical study on that. Anita Retan did this study, in which, it’s called the fragility of innocence, right, where they gave a factual scenario to participants in the study. And it was actually, the factual scenario was straight out of one of those “life without parole” cases. And it was about a teenager who had committed this brutal rape of an elderly woman. And in the fact pattern, they manipulated the race of the participants. So some, let’s say half, of the participants got the same scenario with a black child. And then the other half got it with a white child, every single person was given information about adolescence, the mitigating features of adolescence and the alternative rehabilitative responses to adolescents. So everybody had the same knowledge about adolescents. But guess who decided, who was in favor of severe life without parole sentences? It was those participants who believed the kids were black, when they believed that the kids were white, they were in favor of these alternative approaches, these rehabilitative approaches to white children who engaged in the exact same factual behavior. So that just shows you how we’re willing to give the developmental benefits, the mitigation, to white youth, but not to black youth.

Josh Hoe

But there’s also an I think your that actually brings the other problem to bear, you know, which is, you know, we started this thing talking about Tamir Rice, you and I see Tamir Rice, and we go, how could anyone shoot that kid, the officer clearly saw Tamir Rice and said that kid is dangerous, I better shoot him, you know, we can come up with a million different ways. We’ve seen all across the country even you know, school boards, where people are getting up and screaming about even the existence of racism. But you know, I think you and I would probably come up with 1000s of examples that we see almost every day that seem overtly, and if not systemically racist, pretty damn close all the time. You know, there seems to be a serious disconnect. And we can pass policy after policy after policy. But how do we get to that cultural reality? And this is obviously the million-dollar question for everyone who deals with these issues. But what’s your take on how we start to see, to make people start to see a kid as a kid and not as a target again?

Kristin Henning

Yeah, I mean, you’re absolutely right. I say that all the time. It is the ultimate question. It’s a question of cultural shift. Right? It’s a question of how do we, as a country, get the world to see black children as children too. And I think, you know, there are several things we’re not, you know, I mean, the quintessential piece is, really understanding other people’s story and other people’s reality. And so as Bryan Stevenson would say, getting proximate, with those young people that you’re afraid of, such that you really began to see them as, as, as just as your own children, as you would see your own children, right. So stripping off the fear, and the secrecy and the veil of danger and threat, because you get to know them, you see them laugh, and you see them, you know, thrive in the way that your own children do. And one of the ways to do that is to get proximate. Right. I like to say this, a psychologist friend taught me this once was, and I just loved it, is the idea that every single child needs at least one irrationally caring adult in their lives, and that a child would do even better to have a team of irrationally caring adults. And so what does that mean? It means that we all make mistakes, and we especially made mistakes during our teenage years, but that I will support you and redirect you and, you know, give you alternative courses, to get you you know, to help you move away from that mistake, but I’m still going to care for you. I’m not going to embarrass you, humiliate you, criminalize you, lock you under a jail, but I’m going to do everything that I can to support you. Irrationally caring adults, just like a parent is with their own child, even when a child does something stupid, they still care about them. And so I think that’s part of how we get to that cultural shift.

Josh Hoe

My friend, Amanda Alexander always talks about the power of dreaming big and of having freedom dreams. This season, I’m asking folks what dreams they have about changing our system. Do you have any freedom dreams you’d like to share with us?

Kristin Henning

I think I gotta circle back to where I started. It’s like, let kids be kids, and especially let Black kids be kids. And so I think that’s one dream. And I think another dream is, we have to radically reduce the footprint of police in the lives of all children, but especially black children who have been so disproportionately targeted. You know, even by presence, even, we really have to, as a country, stop relying on traditional law enforcement strategies and policing to do those things that we don’t need police officers to do, right? It’s not an abolitionist argument, this is an argument, let’s relieve police officers of those duties that they don’t need, like regulating adolescents, or like, you know, handling drug addiction and mental illness, relieve them of those duties so that they can do what we really need them to do, and what they’re uniquely trained to do, which is to, you know, investigate offenses and be fair and equitable.

Josh Hoe

Reading this book, a lot of the books I read make me kind of grumpy, frustrated, and angry. But this is one of them that made me angry. Usually, I ask about hobbies, and if you have any hobbies, feel free to talk about those. But I also just wonder, how did writing this book, a book that has these many stories that could make you feel, you know, everything from cynical to angry to hopeless? How did you deal with it from a self-care perspective?

Kristin Henning

Yeah, it’s a good question. Because this was indeed extraordinarily hard to write. It’s hard to be a black woman in America, and not have some direct contact with the criminal legal system, whether it’s a cousin or, you know, a nephew, neighbor, or somebody. And that’s certainly true for me, my brother was in the system. And so I found myself unexpectedly having to psychologically relieve some of that, and that appears in the book. I also found that, as I went back and revisited some of my clients’ stories, that I was experiencing some level of secondary trauma in ways that also were shocking to me. And I kept thinking to myself, if it’s this traumatic for me on review, right, imagine how even more traumatic it was in the moment for the young person. So all that to say, you know, just affirming what you said about how difficult was it to write? And I think, for me, it’s a function of, you know, faith, that there will be reform eventually, that we have to stay the course as Martin Luther King, said, the arc of justice, the moral arc of justice is long, but it leads, or the moral arc of the universe, excuse me, is long, but it leans towards justice. And so I have to believe that.

Josh Hoe

I try to work hard to keep believing it, but some days I’m not so sure.

Kristin Henning

I have those days too. Let’s be clear.

Josh Hoe

I know you wrote a book, we’re talking about your book, but I also like to ask people if there are any criminal justice-related books that they like and might recommend to our listeners. Do you have any other favorite books, aside from yours?

Kristin Henning

Yeah, Chokehold by Paul Butler. Basically, his premise is, this is the way the system works, exactly how it was designed to work. I think it’s a very powerful statement. I would put it on the list, for sure. James Forman’s book Locking Up Our Own.

Josh Hoe

One of the interviews I had, one of the first good interviews I had, he was nice enough to come onto the podcast.

Kristin Henning

Oh, great. I’m so glad to hear that. He’s a good, good friend. So definitely, his book. Policing the Black Man, which is an anthology edited by Angela Davis. I would recommend that one and of course, you know, Michelle Alexander’s, The New Jim Crow. So that’s a lot of those that have been really influential in my thinking.

Josh Hoe

And how would you recommend people find your book? and feel free to say the title again, so everyone gets it.

Kristin Henning

Absolutely! The Rage of Innocence, How America Criminalizes Black Youth and it is truly available wherever books are sold, you know, the big box stores as well as the independent bookstores. Also, if you go to my website, rageofinnocence.com, you can find more about the book, and more about the work that I’m doing at Georgetown Law School, in partnership with a number of organizations like the Gault Center, to really resist some of the racial disparities and racial injustices in the juvenile legal system; our Ambassadors for Racial Justice Program, our racial justice toolkit, and racial justice training series. We have a lot of programs that we’re trying to take this book and actualize reform. What does reform look like? But The Rage of Innocence, How America Criminalizes Black Youth. We talk a lot in this country about the need for police reform. But the need for police reform around children in particular, and black children, in particular, requires a special talent. And so that’s what this book does.

Josh Hoe

I always ask the same last question. What did I mess up? What questions should I have asked but did not?

Kristin Henning

None at all, I think you got it. And I will say this may be as my last point, which is that, you know, this book weaves together stories. So that this book is about giving voice to children who have been impacted by this criminalization and hyper surveillance and dehumanizing punitive responses, even to their mistakes. And I weave those stories together with the research and the data in what I hope will be plain language. So it’s a mass press book. It’s meant for everyone. And it’s not an academic legal text only. So I hope that folks will be interested in reading [it].

Josh Hoe

I think one of the really powerful things about the book is you do a great job of presenting stories, [and] backing it up with all the data. I know you’re at Georgetown Law. So if you get a chance to say hi to my friend Sean Hopwood, please do. And thanks so much for doing this. It was a real pleasure to talk to you.

Kristin Henning

All right, you too. Thank you so much for having me, Josh. And for, you know, having this podcast that covers so many of the books on the criminal legal system and the juvenile legal system. So thank you.

Josh Hoe

And now my take.

I won’t deny it, I’m starting to get a little bit worried about the state of things. In just a few weeks or months, the Supreme Court is about to announce that Roe vs. Wade has been overturned, and millions of women will wake up finding out that something that had been considered a fundamental right only days before, and for most of their entire lives, will be criminalized only a few days later. A cadre of true believers spent decades circling the wagons and figuring out how to leverage geography to subvert the majority opinion, use their access to the presidency whenever they had it, to pack the courts and the Supreme Court. And to do all this, while at the same time convincing a large number of Americans that the mostly moderate to a fault Democratic Party were the real radicals.

And now I think we find ourselves at a real inflection point. And at risk of heading in a direction we won’t soon be able to come back from.

This is a group of people who’ve been able to convince huge numbers of what appear to be mostly elderly voters, that Black people are the real racists, that white people are really the ones who are oppressed, the anti-black racism doesn’t exist, that homophobia is a good thing. And the real problems we have could all be fixed if we can only send women back to the kitchen.

They believe that all of this could be even better if women stopped having jobs, were denied birth control and weren’t allowed to have abortions, and started instead to have more babies. I totally understand that people have different opinions about abortion. But these folks are getting into seriously terrifying territory. And they are very serious in the hands of someone like Ron DeSantis, who if allowed, I’m pretty sure would take great glee in running down his political enemies with tanks. Or a second Donald Trump term with a newly elected and revanchist GOP majority in both houses of Congress. God help us all. Look, say what you will about the Democrats. They are wildly timid and moderate to a fault. But they have no ambition to messianic power. While almost every single person in this new GOP seems to want nothing more than total power, and actually think that anyone who disagrees with them is probably not worthy of legal personhood, much less legal protection.

We’re going to have to stand up and make a stand very soon. These people are coming. They’ve been organizing for decades, and they are very serious. Sorry to be so pessimistic. We’re getting to the point where this is about the survival of most everything most of us care about, and certainly, the people most vulnerable are going to be people who are justice-impacted in a world in which fear of crime

is one of the prime touchstones for most of these folks. And I’m not sure what to do. But I do know, it’s really just about time for all of us to get together and start to do whatever we can.

As always, you can find the show notes and/or leave us a comment at DecarcerationNation.com.

If you want to support the podcast directly, you can do so at patreon.com/decarcerationnation; all proceeds will go to sponsoring our volunteers and supporting the podcast directly. For those of you who prefer to make a one-time donation, you can now go to our website and make your donation there. Thanks to all of you who have joined us from Patreon or made a donation.

You can also support us in non-monetary ways by leaving a five-star review on iTunes or by adding us on Stitcher, Spotify, or your favorite podcast app. Please be sure to add us on Instagram, Facebook, and Twitter and share our posts across your network.

Special thanks to Andrew Stein who does the podcast editing and post-production for me; to Ann Espo, who’s helping out with transcript editing and graphics for our website and Twitter; and to Alex Mayo, who helps with our website.

Make sure to add us on social media and share our posts across your networks.

Also, thanks to my employer, Safe & Just Michigan, for helping to support the DecarcerationNation podcast.

Thanks so much for listening; see you next time!

Decarceration Nation is a podcast about radically re-imagining America’s criminal justice system. If you enjoy the podcast we hope you will subscribe and leave a rating or review on iTunes. We will try to answer all honest questions or comments that are left on this site. We hope fans will help support Decarceration Nation by supporting us on Patreon.