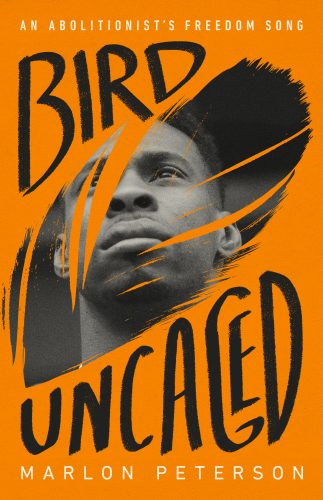

Joshua B. Hoe interviews Marlon Peterson about his book “Bird Uncaged: An Abolitionist’s Freedom Song.”

Full Episode

My Guest: Marlon Peterson

Marlon Peterson is the principal of the Precedential Group Social Enterprises. He is the host of the Decarcerated Podcast, a Senior Atlantic Institute Fellow for Racial Equity, a Civil Society Fellow of the Aspen Leadership Network, and a 2015 recipient of the Soros Justice Fellowship. Ebony Magazine has named him one of America’s 100 most inspiring leaders in the black community. His TED talk, “Am I not human? A Call for Criminal Justice Reform,” has over 1.2 million views. And he is the author of the recently released book we are here to discuss today “Bird Uncaged: An Abolitionist’s Freedom Song.”

Notes from Episode 102 Marlon Peterson

You can find Marlon’s book on Indiebound.

Mariame Kaba’s book is called “We Do This Til’ We Free Us.”

Reginald Dwayne Betts book is called “Felon.” His earlier book was called “Bastards of the Reagan Era.”

Full Transcript: 102 Marlon Peterson

Josh Hoe

Hello and welcome to Episode 102 of the Decarceration Nation podcast, a podcast about radically reimagining America’s criminal justice system.

I’m Josh Hoe, and among other things, I’m formerly incarcerated; a freelance writer; a criminal justice reform advocate; a policy analyst; and the author of the book Writing Your Own Best Story: Addiction and Living Hope.

Today’s episode is my interview with Marlon Peterson about his new book, Bird Uncaged: An Abolitionist’s Freedom Song. Marlon Peterson is the Principal of the Precedential Group Social Enterprises. He is the host of the Decarcerate Podcast, a Senior Atlantic Institute Fellow for Racial Equity, a Civil Society Fellow at the Aspen Leadership Network, and a 2015 recipient of the Soros Justice Fellowship. Ebony Magazine has named him one of America’s 100 Most Inspiring Leaders in the Black Community. His TED Talk, Am I Not Human?, a call for criminal justice reform, has over 1.2 million views. And he’s the author of the recently-released book we are here to discuss today, Bird Uncaged: An Abolitionist’s Freedom Song. Great to talk to you again, Marlon; we talked about doing something like this a few years ago, and I’m glad it finally happened. Welcome to the Decarceration Nation podcast.

Marlon Peterson

Hi, thanks for having me. It’s happened at the right time.

Joshua Hoe

Yeah, for sure. I always ask the same first question. It’s kind of the comic book origin story question. How did you get from wherever you started in life to where you were doing whatever you came on the podcast to discuss? But since your book is the story of your life, in a lot of ways, maybe just give an idea of your journey? Can you summarize where the book starts, where it goes and where it ends?

Marlon Peterson

Thank you for that. I like that question. The book starts in Brooklyn; actually, the book starts in Trinidad, and then eventually goes to Brooklyn, New York. And it ends, in many ways it ends in different parts of the world. Because the perspective of it, where I get to at the end of the book, is based largely on my being able to experience different parts of the world, and experiencing issues of incarceration or witnessing issues of incarceration and trauma in different parts of the world. So that’s pretty much where it ends.

Joshua Hoe

There is a lot of trauma in this book. And I know you’re doing a lot of interviews, and probably a book tour, right, pretty soon. How are you handling continuously talking about these really serious and personal issues? I know I struggle with this myself sometimes, and I’m sure a lot of listeners do as well. What are your thoughts on maintaining your own wellness while doing this work?

Marlon Peterson

I take breaks from it. I have, first of all, just like you, you and I have a similar background, as you just mentioned, and it’s not new to be talking about traumatic experiences for me. I think, though, that obviously, this book is in such great detail, I don’t think I have ever required that of myself, but I take breaks from it. I actually don’t pay attention as much to issues within the field of criminal justice, like right now. I actually take a step away from it a little bit, but I need to breathe away from it a little bit more, I need to be more intentional about breathing away from it. Because I’m talking about so many things that’s so heavy, that’s a part of it, so I don’t want to take on more. Right now I’m pretty much in the beginning stages of this whole book tour thing, the book just came out April 13, yesterday, so I’m just adjusting to it right now. So even before this – I had to do an engagement earlier this morning – and I came home and just took a nap. It was very draining. And I have you and I have another one after you, but I’m also doing this for other people. I also understand that I didn’t write this book because I just wanted to talk about myself. I understood that every page [of the] book can be relatable to other people also, instead of me, talking about [it] is also giving life to other people.

Joshua Hoe

I think we’re all familiar with a kind of normal narrative where there’s lots of just regular characters, human beings [but] there are a lot of non-traditional characters in your book; one of them is religion. Can you talk about where you started as a Jehovah’s Witness and where you are now, how or what that evolution has been?

Marlon Peterson

Wow, you know, I really appreciate that question. Because one of the chapters is called, “I’m Losing my Religion”. I was raised as a Jehovah’s Witness, and in many ways that foundation is why I’m able to speak publicly and try and interact with people who may not really care about what I got to say. You can see it’s pretty much doing that, right? You got to speak about things to people who probably don’t care about what you have to say, and Jehovah’s Witnesses get doors slammed in their face a lot. And I was getting doors slammed in my face as a little child, so I’m accustomed to it. But also, religion has played a role, a pivotal role, in my life, not only because I was raised as such, but I think I had struggled as a teenager with believing that religion was the right thing for me, because I didn’t believe that religion was protecting me. I mean, I didn’t believe God was protecting me; let me be more specific. But then again, when I went inside, religion is what I gravitated back to, right? And I was facing a life sentence. I mean, it was very real. It wasn’t a joke, like they weren’t bluffing, trust me when I say that. And I say that even the District Attorney to this day will say the same thing. So, um, I was desperate. And I almost had just got back to religion because I was desperate. But it provided a level of guidance for me. I was 19 when I went in; I remember for the first couple of years, I was always placed in housing units with people . . . . And I didn’t know how to adjust to prison, I didn’t know prison, I was arrested once before but I spent a couple of hours in jail, I was never housed in jail. So in many ways religion helped me; I matured in some ways, to understand and interact with people in a way that was mutually beneficial and definitely not harmful to one of us. I’m no longer a religious person. But I definitely appreciate a lot of the teachings in terms of just public speaking that I’ve gotten, and also some values I’ve gotten from it, from that stage in my life.

Joshua Hoe

I myself am a recovering musician. And another kind of non-traditional character in the book is the steelpan. Can you talk about that as well as how central music is to your story and your history?

Marlon Peterson

So far, you are the best interview I’ve had. I love these questions. I love the nuance and texture to these questions. Yeah, the steelpan instrument of the Caribbean, Trinidad and Tobago, I still play, actually, I play a six-bass in the summertime we have a band here and we’ve won competitions. Prior to my incarceration, I would play during summers with different bands. And it was one of the places where I felt the safest, I had to leave my block or my neighborhood to go practice and in many ways that gave me a sense of peace, going to play the instrument. And I avoided a lot of things on my own block or my own neighborhood when I was away playing the steelpan. So when I was inside, I didn’t have access to any of that sort of stuff, but you know, every once in a while, depending on what jail I was in, I would be able to get a radio station that might play the steelpan – or just from memory, it’s amazing what music can do in terms of how it can get lodged into your brain. And I can just remember, and hear some of the music that we used to play in my head, and even dance to it in my cell or whatnot. You know, another thing that gave me a sense of peace while I was away, is one of the reasons why I still play today. And lastly, I want to say you know, in a TED talk, I speak about the steelpan. Because I use the analogy that you know, the steelpan was created in a neighborhood in a time where people looked down upon people playing the steelpan, right. My father, he played the steelpan as a young man in Trinidad, and people looked down on him because they thought it was from the ghetto. And it’s not people who are worthy of anything. But yes, so these people created an instrument, the only acoustic instrument invented in the 20th century in the world, and that instrument is now everywhere in the world, right. And in so many ways I think it’s indicative of people who have come from some communities, just like mine, who have had the carceral experience like mine, where people think they are worthless, there’s nothing that can come of us. And yet still, we can create amazing things for all people that benefit from it.

Joshua Hoe

I still remember when I was a kid, I mean, it’s such a joyful music. I remember walking around New York City, and you’d run into people playing the steelpan. I remember it like it was yesterday, and I was just a little kid. I really resonated with that part of the book. Another, maybe even more underlying character in the book that only gets mentioned a few times but I think is very important is Maya Angelou; could you talk a little bit about her influence too?

Marlon Peterson

You did your research!

Josh Hoe

Yeah, I do. I do read the books.

Marlon Peterson

This is wonderful! On Maya Angelou – so we’ve all been, I mean, I will say I don’t want to assume everyone who’s listening has ever …. Yeah I do wanna make an assumption. If you haven’t heard about Maya Angelou, you need to sort of check yourself and look in the mirror and ask yourself why. For me, I had definitely heard about Maya Angeloue before I was incarcerated, mainly from a topical way right? Not anything too in-depth about her life, and inside I ended up reading her book. I read her book, her first book, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings. I read her book when I was actually keeplocked. And keeplock, it’s not the box quite. It’s not you know you’re not in a dry cell but you are locked in your cell. You only come out for one hour a day. And not even one hour a day; you come out, take a shower, that sort of thing every couple of days. And I was keeplocked for 45 days, and the book somehow got in my possession. I don’t know the story of it, but a book got into my possession, and I just felt connected to it. I felt really connected to her story, even though she was a girl growing up in rural Alabama, back in the day. I’m a guy growing up in Brooklyn, you know, 20th-21st century at that time, the 21st century, definitely two different places, but I connected with it. And I think the metaphor of the caged bird sings – I was in a cage. And at that point, I remember being very distant, in a deeply dark place. Right. Being in jail is one thing, but being in jail within jail is a whole other thing. I think it just resonated with me, her ability, the way in which she understands; she went mute for a period of time after that incident that happened and she blamed herself for, but she ended up reading everything in that time when she went mute, and in so many ways it’s what made her the Maya Angelou that we know today. The other part of it that I love – since then, I’ve studied, become a fan of hers – deeply – probably even stalked her through YouTube – is that she lived a full life. She was known for being this great poet, but she was also a Soca singer. She was a dancer, she traveled and lived in Ghana for years, like she did. She worked with Malcolm X and Martin Luther King, you know, she just lived such a full life. And I think that’s the sort of life that I want to live, I want to live a full life, do the work that I care about. But I also get to have many iterations of myself, I get to have multiple expressions of myself, like, you know, we say it all the time, right? Like incarceration doesn’t have to define us, we know that, right. And we want to encourage people to also see that, but we also want to encourage people who have had these experiences to see that your life doesn’t have – not only your life in terms of how people view you – but you also get to expand how and what what you appreciate about the world outside the carceral space. I don’t think because we went to jail, our mind is always supposed to be connected to jail. I don’t think we ever are supposed to forget about the people there, and the experiences we had there. But everybody doesn’t have to be an advocate. That’s fine. Not everybody’s got to be activists, and that’s fine. Everybody does not have to have a podcast about prison, that’s fine. Because those of us who choose to do that, even for those of us who choose to do that, we get to like other things and have different . . . if you want to become a farmer, or if you want to become a, I don’t know, a musician again, right? You get to do that. And I think that’s why we came out of prison, to be able to do whatever [it is] that we love, our heart’s desire.

Joshua Hoe

That’s such an important point there. I was just talking to Maurice Chammah a couple days ago, a couple of weeks ago, about how sometimes it can be exhausting, where every single conversation you’re in, seems to have to go back through the exact same territory; sometimes it is good to be other things for a while.

Marlon Peterson

Yeah, it is important, because you also got to give space to other people. I remember being a younger person inside. And you know, they’ll be the old-timers, you know, I can’t believe that’s my age now. Right? But, sometimes you need people to also allow the younger folks space to step into what they need to step into. I think sometimes people who’ve been in the game for a long time, or who’ve been doing this work that you and I do all these years, sometimes it’s okay to be, all right, somebody else can do it, because they also experienced incarceration differently. But I noticed that there’s things about incarceration that never will change based on whether you were in jail in the 60s, 80s, or the 21st century; something about the pain, the trauma, the harm and all that is so very much a part of the fabric of incarceration. But nowadays people got access to tablets. I didn’t have it! If you had anything remote, anything other than the Walkman, or radio that you had, you was going to the box! I’m not saying good for them. But I’m saying they also experienced incarceration differently. And their experience between being incarcerated and the way they’re able to experience the outside world is a little bit different.

Josh Hoe

Yeah, it’s also going to be pretty surprising to some of the old guys in there who had never seen a computer at all. And now they can get a tablet and stuff like that.

Marlon Peterson

I imagine. I mean, this happens to some old people out here. I had a friend yesterday, who’s my age, yesterday ask how do I send a friend request on Facebook? He’s my age. I mean, he’s out. Yeah, he didn’t do prison. So I’m just saying there are those of us out here.

Joshua Hoe

There’s a lot of serious stuff in this book, and we’re gonna talk about that for sure. But I’ve got to ask one lighter question at least – and that’s because you know, it is a real big part of my life too – basketball seems to be a big character in the book. It’s a big part of my life, it was a big part of my time in prison. Do you still play?

Marlon Peterson

Why you gotta ask me do I still play, man? I want to play.

Joshua Hoe

I don’t play anywhere near as much as I used to; I’ve got a bad knee too.

Marlon Peterson

‘m mad about that. I’m sorry, I haven’t actually played basketball, maybe in a good year and a half now. I have a mild tear in my ACL on my right knee. So that stopped me. That’s the only thing that stopped me. I would still be playing. But in the book, I mean, definitely, for the first couple of years of my incarceration, basketball was the closest thing to being . . . here’s the thing, in prison, at least for me, there was ways in which in my mind, I was creating measures of freedom for myself, right. I’m the only person that understood why I was so enthralled in it. So listening to steelpan music or listening to music on my Walkman was one way that took me out of it. A second way that took me out of prison was when I would write to myself; I have journals. And a third way I would take myself out of prison was when I played basketball. And there’ll be times when nobody else would go, just before I was sent to the state prison. So in a city jail, you go to the yard by housing unit, and the whole jail doesn’t go to the yard at the same time. And oftentimes, nobody would go to the yard to play ball, particularly if it was cold in the wintertime and had snow. And I would go up there in the yard, I would move the snow to the side. And I would dribble a basketball. And it would be me and the world. And I would literally be having the time and – for what it’s worth – the time of my life, in the sense of imagining I’m not there. And then as soon as it was time for that hour of rec to be done, I was like, prison.

Joshua Hoe

Yeah, it does kind of transport you though, because you know, basketball is basketball. You know, if you’re on a court, you do feel different than if you’re in …. at least it was for me; I agree with you.

Marlon Peterson

Yeah that was pivotal. You know, it still is. It doesn’t play a huge role in my life … I interact with it. I mean, I still watch it, obviously. I mean, very much, I’m very much engaged. My dream Josh – just me putting it out there – my dream is to have courtside seats to the Knicks. I don’t know where I’m gonna get that type of money. But like, that’s a fantasy of mine.

Joshua Hoe

Maybe you can get Spike Lee to loan you his every once in a while or whatever. I don’t know, or did he get knocked? I can’t remember; I know Dawn was mad at him for a while.

Marlon Peterson

Here’s the thing about Spike Lee, is that the first time I ever wrote publicly – I think I might not have put this in the book.

Joshua Hoe

You did, yeah, you did.

Marlon Peterson

I was in the seventh grade going into eighth grade. And I was part of this summer program that Spike Lee sponsored and Nike sponsored, that allowed kids to be citizen journalists. And I would interview people. And here’s the thing; I don’t think I put this in the book. But one of the places, one of the places that they had us visit as kids was a jail.

Joshua Hoe

Yeah, that’s in the book. Yeah, you say that your teacher took you there.

Marlon Peterson

Yeah. And you know, the only thing I remember is some men saying that you come in jail, you’ll get cut, or you’ll get cut in your face. And the reason why I think I probably speak about it in the way that I do in the book is because I want to show that I remember that story, but that didn’t deter me from doing things, right. You know, sort of like this sketch street is sort of that thing. But we weren’t kids who were seen as delinquent, we were kids who were, as I said, citizen journalists, but they still used the same scared straight school for us. And it did nothing for me. And I just remember that the only thing that stuck in my head is that when I went to jail years later I was like, geez, I don’t want to be in no situation where I get cut, or I have to cut someone. But it was never like a deterrent; I didn’t learn a lesson from that visit.

Joshua Hoe

Yeah, I think there’s this assumption that that stuff, somehow jail, and maybe it does for some people, but I don’t know. So a final non-traditional character – I think I’m reaching a little bit here, but I do think it’s pretty present throughout the book – is secrecy. Where have you come to in terms of how you try to be present in terms of truth-telling, mask-wearing emotional honesty, that kind of stuff? Because you’ve obviously made a long journey there.

Marlon Peterson

Yeah, definitely a long journey. I mean, I’m definitely much better at that in terms of unmasking. I’m more of myself and more comfortable with myself. I’m more comfortable with being honest with myself. The first chapter of the book is called “Hiding”, right? And I speak about it in so many ways, the genesis of my hiding, and that’s why it starts in Trinidad. I mean, I wasn’t born in Trinidad, my parents were, but you know, I speak to the genesis of it, why hiding was a thing that in so many ways – taking a quote out of the book – it was part of a cage that I created for myself. But it was also influenced by external things that were happening outside of me and around me. As I’ve grown, as I’ve evolved, matured, gotten older, I have realized that some of these masks, all the masks that I’ve worn or I felt committed to, have harmed me more than they’ve helped me. And also I realized that there were certain masks that everybody wears in prison. I mean, it’s a way you survive, right? You wear some type of mask in prison, and it is necessary in some ways, right? Masks keep you safe. And, also those masks – I spent a decade there, right – so it became part of my character in terms of the masks that I wore. So I had to unmask that and it took time, right. So I’m home 11 years now. And I didn’t realize some of the things I was carrying were still with me, because I was still able to flourish professionally, right. But you know, you read the bios, and all the things I’ve been able to do since I’ve been home, but one of the things I was not realizing up until maybe pretty much in the process of writing this book, like how I was wearing some of those sort of masks, really emotional masks, that was harming not only me, but was harming people who were coming close to me, right. I was still in so many ways, protecting myself, my innermost self, from people, because that’s what got me through prison for the most part. I definitely connected with people, I connected with people in prison, but not in a way that showed my vulnerability. I connected with people knowing that people felt that they can share their vulnerability with me, but I didn’t have to give anything back, [it was] sort of just like, one-sided. And I realized – this is where I’m going with this Joshua; I’m talking about an intimate space, like relationships. Even [the] familiar, like close family, has to be reciprocal, and in so many ways I was preventing people from getting to the deepest parts of me.

Joshua Hoe

Your book addresses some really tough aspects of growing up as young men in America: toxic masculinity, emphasizing toughness before looking for help, healing from trauma. I know this is a big question, but what do we as a society get wrong about how we raise young boys and men from your perspective?

Marlon Peterson

Um, we get a lot wrong. I think we miss a lot of cues; I don’t think we listen to boys. I want to say this could apply to anybody within the gender spectrum, right. But I definitely think about boys, particularly boys in certain communities. I think a DMX is the best way to think about it right? For years just in terms of how we knew him as an artist, he was expressing himself. He was expressing himself about his childhood. And obviously, it was music to us. And some of us understood it. Some of us didn’t. But we were dancing to it, but he was literally telling us about all the things he was dealing with. And it was in a brash way. It was in an aggressive way. I mean, he was barking, but he was an adult, you know, he was literally barking these stories out. And I think that everything about boys – we’re raised to be super tough, macho, we don’t cry and all that sort of nonsense. And we’re raised like that, we’re conditioned like that from infancy. You know, the first time a boy cries, you tell him, you know, he falls on the floor, don’t cry. Right? You know, we’ve heard that story a million times. But what we don’t understand is that when you ingrain that into a young person from infancy, they learn to hold emotions. But they’re also trained that the way that they’re heard is by being loud, by being super-aggressive and brash. They’re still expressing themselves, young boys are still expressing themselves. But it comes across as maybe too aggressive, and I don’t think we are listening really, we’re not listening to the little DMX and a lot of our little boys, right. And for me, I kind of like bringing myself into the story. Like in my household, I wasn’t necessarily raised to be just tough, all that sort of stuff. But I was also raised in Crown Heights, Brooklyn, right. I was also raised in the schools I went to so I picked up on some of those traits. And so the ways that I wanted to express myself, people couldn’t really relate to it when I attempted to on a few times. So what did I do? just kept it to myself, cuz that’s the other thing we know, right? You don’t cry; when you tell a young person, you’re not supposed to cry, you tell them they’re not supposed to express themselves. You’re not supposed to tell what’s going on with you, what’s bothering you; or what so many of you are crying for joy, that’s gonna tell him what, why you’re happy. And I’m saying that as I got older, when young boys get older, when they’re in school, even elementary school, definitely in high school, at least high school age, they are now conditioned to hold that stuff in. I’m gonna hold it in, but it’s gonna come out in an aggressive way. Right? That’s a roundabout way of saying it, but I think ultimately, we need to do a better job at listening to little black boys. And allow little black boys to be little black boys, and then stop seeing little black boys as big black men. Oh, and that’s not only a racial thing, right? That happens with little Latino boys too, that’s sort of ingrained in them that they have to be tough or hold it in. And that doesn’t help anybody.

Joshua Hoe

You also address kind of personal struggles with appearance, the pressure to fit in, societal standards of what’s expected, sexual insecurity, coming to grips with inappropriate behaviors. Obviously, I’ve had to make a lot of that journey myself, too. Can you talk about where you are now? And what do you think the answers for you are in terms of healthy relationships? How have you come to grips with all that? I mean, it’s very brave the way you talk about it in the book, and I just want to make sure that people hear where you are on that.

Marlon Peterson

Yeah, absolutely. Well, one of the things I had to recognize was that there were behaviors, that these behaviors were . I mean, in so many ways, a lot of things, what I spoke about in the book, was seemingly wrong even at the time, but it also was what everybody was doing. In my mind it’s like, it’s not that wrong, or it may not be nice, but it’s, you know, that’s how boys do. And I think, you know, growing up, but not only growing up, but the process of writing this book, and yes, also evolving as a person, I’ve had to first acknowledge how harmful my behavior was, and how harmful my thinking was. And so now, I obviously, don’t engage, I don’t’ want to say obviously because people already know me like that, you know, I haven’t grown to forget how I thought, but I understand there’s no utility in how I thought anymore; I no longer need that thinking, not only because it’s harmful to other people – women in particular – but it’s harmful to me, right? Like I just when I’m disrespecting other folks, other women or women in various ways, I’m disrespecting myself, or what I believe myself to be or where I want to be, or where I want to go. So the reckoning that I’ve had to do, particularly with this book, because, you know, in the parts that you’re sort of referring to, in the book, I’m going through, I’m literally writing stuff out on my computer, writing those passages or those sentences, and, like, shaking my head. I’m writing it, I’m shaking my head, I’m like, Oh, my God, Marlon, oh my God, you know what I mean? And, you know, I think once again, sometimes getting to where I’ve gotten requires work, requires really tough personal work and therapy too, you know what I mean? Yeah, personal work. And the thing about it is that it can’t be done in front of people, you can’t perform this sort of work. It just has to be done with you. Right. It’s not for performance purposes, because if you’re doing it for performance purposes then obviously, it’s not real. But I mean, and I want to say, it’s not like you do the work, I’ve done the work, and I have arrived, I’m a perfect man now. Right? It requires me – because I’ve become aware of what I used to do and how I used to think – those things, those thoughts are still in me, but the only difference now is that I’m much more conscious of it so that I interrupt it before it becomes action, or something that comes out of my mouth.

Joshua Hoe

I think for most of our lives, and I don’t think we’re that dissimilar in age, we’ve heard the excuse that even if we weren’t a perfect country, we were still making progress. But I think over the last five years, some of the masks have been ripped off of that. And we have seen anything but progress when it comes to, for instance, racism or structural racism. I think a very big part of your book is a story of race in America. Do you want to talk about that aspect of your book?

Marlon Peterson

Hmm, yeah. Because you know, in this book, obviously I speak a lot about my life and my personal life and you know, a lot of things in my journey, but I’m also keenly aware that my journey is not in a vacuum; my experience is what a lot of people in my neighborhood or communities like mine experience. So that pushed me to think about, well, why is that so many of us have these types of reactions and these experiences? Why is it that when I’m in prison, so many people look like me, and they’re all young, and why are the majority of people who are in this jail with me, in that prison with me, in my age group, within a 10-year age group? Why is that happening? So maybe we look deeper into that beyond just like what we do in interpersonal harm, but the harm which is done to particularly black and brown folks in America. So in the book, I’m hard on myself, but I’m also hard on the country, right? Because I understand that when you see violence in Chicago or Crown Heights or Inglewood, or whatever urban center you want to think about in America, it’s important for us to also understand that these urban centers where violence is happening are not divorced from where state violence is happening in our communities. I speak about police stalking me as a young child, with my even younger nephew, who’s at the time like a baby, eight years old, right? And for no reason other than to harass us. And to me, you know that incident in and of itself, as a young kid, I was oh, wow, well, you see, I’m a crook. Like I just I was coming from steelpan practice in a pair of shorts in the summertime, with my nephew in a pair of shorts and a T shirt; my nephew was eight. But I know, I reflect back on that moment, I understood, the message that I got was not that police were trying to protect the streets; the message that I got was, Oh, I’m a problem. And I could potentially be a criminal. Even if I’m not doing anything. Because at that point in my life, I wasn’t doing anything; I wasn’t outside hanging out doing that sort of stuff. And so I don’t let go of race in America, right. And particularly towards the end of the book, I speak about it because it was written during the time of the uprisings last summer throughout the country. A lot of my work, even before this book, obviously has an intersection of police violence, state violence and race. That’s where my work has been. And I’m wanting to make sure that people understand that ….. black and brown folks in our community are not just born to hurt and harm each other, that we are influenced by a lot of things. We’re definitely influenced by the way we inform each other at young ages, and maybe in a harmful way. But also very much informed by the way the state and racism play a role in our lives. I might not have a cross burning on a corner. You know what I mean? I might not have a tree with a noose hanging from it down the block or whatnot. But we still see the residues of it, we still feel it, you can watch it on the news. And we know that we’re the ones who are still somewhat on the chopping blocks. And that impacts us, like we in so many ways we understand, even in our subconscious, we’re aware, [that] our skin color, our complexion and where we live is a threat to other people. And even if we have never done anything to anybody, physically, we understand, we get that messaging. And I want to really be clear about that. Like that messaging is a part of the problem, a huge part of the problem, probably a major part of the problem, of why we see what’s happening in neighborhoods like mine or Inglewood, or Chicago, or Jackson, Mississippi, or what have you.

Joshua Hoe

o it’s interesting, because I think with you and me, who’ve been through the system, we see an increase in dysfunction, or crime or whatever you want to call it in a community. And our first thought is, we need to do something to try to address the problem in that community. And I think when other people see an increase in crime, the first thing they think is we need more arrests; we need more incarceration; and I think both of us do a lot of work to try to break that down, and I think your book does a good job of that. But what would you say back to that now? I think you just had one good answer to it. But when someone comes at you with, well, there’s more crime, we got to protect the community, let’s put more people away. Why is that so wrong?

Marlon Peterson

Well, why? Because history . . if you are in the data collection world, increased policing does not reduce crime. If you’re in the data collection world, you can look at that. Increased incarceration does not reduce crime, if you’re just in the data collection world. Let’s just say that, for those people who are . . .

Josh Hoe

It actually increases crime.

Marlon Peterson

Right. And I’m just gonna just go to that for a second, right? In the data space, but aside from the data, because, you know, the stories are what we really love to hear. When we hear things about, like these shootings. And right now we’re in the middle of a trial in the same city where a police officer just shot another person, right? killed another person. And we think that that’s policing, too. I mean, police leaders, what have you, may not say, law enforcement leaders may not say, well, that’s bad. Yeah, well, that is part of policing. We have to sort of accept that policing, killing black people, is also a part of it. There’s never been a time in American history, where policing didn’t kill black people. It just doesn’t exist. So at this point, we got to say, well, this is a part of policing. It just is. I mean, some people may say it’s bad, when you’re trying to create new policies to try to, reduce it, whatever. But it’s also just very much a part of it, right? It’s a byproduct of policing. And because that’s a byproduct of policing, that is also part of the violence that is in our communities. But I don’t want to divorce the violence that we commit against ourselves from the violence that police commit towards us. It’s all violence. It’s all violence, and gunshots are the same way, and the knee on the neck and all that sort of stuff. It’s all the same thing. It’s the same messaging that everyone is getting. So anything policing … This is not a correlative fact, right. policing, You said like more police will lead to more crime. I don’t know how true that is factually. But I do know, all I will say, is that I know that more policing does not reduce crime. That’s what I definitely know. It just does not. What reduces your harmful behaviors, is first, an addressing of why those harmful behaviors are happening in certain communities, like why poverty is the way it is in certain areas, and then sort of being able to allocate resources to other things, to other social services in our communities, to look at how our education systems are in certain communities, and how can we not only fund them more, but make sure that they’re more relevant to the 21st-century conditions of the people who are attending these schools? Like, those are the things that lead to safer communities. The thing that led even to me doing the work that I do now, right, and now I’m here talking to you on Decarceration Nation, it wasn’t so much like the way I articulate myself now. It wasn’t like I learned this in jail. Right? I didn’t learn this in jail. I understood the context for how to use my words in terms of what field, but I didn’t learn this in jail. What prevented me or what got me from being this 19-year-old kid who was willing to hurt and harm other people, like jail didn’t do anything to me about that. There was a different intervention, which I speak about in the book, where somebody reached out to me and helped me be a part of young people’s lives while I was in prison. That was an intervention I needed; [the] people I needed. I needed my self-esteem to be built. That’s what I needed. And prison does nothing to build self-esteem, nor do police.

Joshua Hoe

That’s for sure.

One thing I noticed that was pretty interesting was while you talked about there being a lot of violence around you in prison, in some way, reading the book, it seems like you were safer in some ways in prison than you had been in your original neighborhood, where you were traumatized a great deal as a young man. What do you think it says, that in some ways, you could be saying that a young black man could be safer in prison than he was in his own neighborhood?

Marlon Peterson

You know, just last night at the book launch that I had with Dr. Nadia Lopez – the person I’m referring to was a teacher who reached out to me to ask me to write some words to her students at the time. She read a letter that I wrote to a student in 2005, [that] I had never seen; I mean, you write a letter, you don’t get a photocopy of it right? When you’re in prison, you write it and it’s gone. So I had never seen the letters that I wrote to any of the kids, you know, since I wrote it, and she read it. And then in this particular letter a student asked me, literally, almost verbatim, do you think it’s safer being in jail than it is out here? And then she referred to things like stray shots, and all the things that happen to her neighborhood, in Fort Greene, Brooklyn at the time, and it made me rethink about it. Right, rethink it. I think about Eddie Ellis, right, who’s a mentor of mine who passed away several years ago. You know, he’s one of the people who have authored a non-traditional approach to criminal and social justice. You know, he would say ….

Joshua Hoe

A lot of really good work on language, too.

Marlon Peterson

Yes, it’s why we call people incarcerated person or whatnot. We don’t say just convict and all that sort of stuff. But one of the things that he had said, what he would say, was that there are no prison problems, there are only community problems; he was trying to just draw us into understanding that what we see in prisons are just a small example of what’s happening outside. I mean, just concentrated harm in prisons, right, where it’s the same thing happening? But you know, it’s just more people in more space. So here’s the thing. I think it’s sad that we live in a society where people question whether it’s safer to be in jail for a black person than is outside, I just really want to say, that is telling on our society, that it might be safer for us to be in a cage, against our will, than for us to be outside, right? It’s just an indictment of society. It’s never better to be in a cage. It’s never better to be in prison. And in some ways, I don’t want to say I was safer. I just understood how to interact with people differently, right. I just decided, I was sort of forced to understand how to interact with people differently. And everybody in prison is walking around scared, right? And I don’t think people see that; everybody’s walking around scared. Everybody knows the stories that they heard about prison before he came to prison. Now people just mask it better, right? And people become better purveyors of harm and other things. But everybody’s scared in there.

Joshua Hoe

And we all see everything that’s happening around us all the time. There’s definitely a lot of violence in prison too.

Marlon Peterson

Yeah, actually I don’t know, in this book, I don’t spend a lot of time talking about the violence in prison, right? I spent a decade, so I saw a lot of violence in prison. But I also saw a lot of violence in my neighborhood. I saw my first violent attack when I was in, I was first violently attacked when I was in the first grade, the first time I’ve ever seen somebody get cut on a face, I was in the third grade, and some fourth graders who did it to each other. You know what I mean? Here’s the thing, I don’t think there’s a place in America necessarily, that is really super-safe just in general terms for black people. You know, inside, not even in prison, because, you know, we don’t hear the stories. But gosh, imagine if we had cameras, openly had cameras in prison, right? How many times would you see police or COs beating down people inside? That happens. It’s sort of like, well, you’re in prison, that’s how we should be. Right? You know, officers beat you up, right. But just imagine if they had cameras inside. I mean, I say openly, right, openly had cameras inside, showing these sort of things. I don’t think that prison is safer for anybody. But I also just really want to say that I think it’s really sad we’re in a society where people are questioning whether a jail is better than freedom.

Joshua Hoe

Definitely sad. You say, towards the end of the book, that “I was 19 years old when I went away; my freedom would be forever connected to the death of innocent people. I knew I’d always be considered an ex-con; how many times would I have to prove to people that I was no longer that 19-year-old boy”? I struggle with this a lot, too. And we talked about it a little bit earlier. Have you come to any conclusions about how to live beyond your crime, but also to live with your crime?

Marlon Peterson

Yeah, yeah. I mean, healing is a personal thing, right? Atonement is a personal thing, right. And similar to like, how we spoke a little bit earlier about the way I interacted and thought about women, and the way I interacted as a child, and where I’m at now; that’s a very personal process in terms of reckoning with myself, and then moving beyond it. I need to move beyond it; if I don’t move on, I can’t be a productive soul. So for me, I’ve definitely healed beyond that 19-year-old boy. And, I’m – I want to say this – I am healing still; that’s why there’s a process, right. But I no longer walk around with the guilt on my shoulder. I always say guilt is the emptiest, is an unhealthy emotion. No, it does no one any good. If I’m walking around with a weight on my shoulder, it doesn’t do, even in the spectrum of you know, the harmed party versus the person who was harmed. The person who committed the harm, someone holding guilt does nothing to help either one move beyond that situation. So we think about, in a restorative justice conversation, guilt is there, but you’ve got to be able to heal beyond the guilt before you can be able to care, how you can deal with somebody else’s pain, it does no one any good. So I no longer walk with that sort of stuff anymore. But I do also understand, I’m sensitive about it, though. I’m not flippant about it, I’m not flippant about the fact that I’m on Decarceration Nation. As you read in my bio, I’ve been able to accomplish things. I’m also not flippant about understanding that I’ve been able to do these things, but it’s also connected to a very tragic thing. I’m very aware of that, right. But I also don’t carry it in a way that’s harmful to me or anybody else. I’m in a way in which I’m understanding why and how I got to where I was at, and also trying to, of course, also trying to prevent other people from walking in our shoes, and that’s important to me. I mean, that’s me sort of getting past it, finding a way not only to help me survive, or heal and thrive, but also understanding that part of the reason why I went through it is so that other people don’t have to go through it.

Joshua Hoe

I think this is probably my favorite part of the book, the way throughout that you tell the story of your parents, how different they both were, but also how important they both are, and have been, in your life. I thought it was really beautiful. Would you like to say anything more about them here now?

Marlon Peterson

Yeah, I love them to death. You know, my father. My first thought with him is that my father, for the first two and a half years of my incarceration – I was remanded – I wasn’t sentenced for almost three years. I spent most of the five years in a city jail. And he visited me every single Friday, every Friday, right? Every Friday, he visited me and if he couldn’t visit for any reason, he would arrange for somebody else to come. And my father now has dementia. At this point, he has no idea what I’m doing. And you know, that hurts a lot Joshua really, that he can’t fully appreciate the fruits of his support of me and his love for me; he can’t because his brain is not allowing him to, but he’s also been a life-giver to me. And my mother, you know, I talked about like, she does a promo I have on my Twitter page, I think it’s pinned on my Twitter page. You know, when I was inside, I had wrote a sticky note to my mother, I wrote a little pink sticky note. And I think I put it in an envelope – it wasn’t even a letter – it was a sticky note that said, Dear Mommy, One day, I’m going to make you proud of me; just watch and see, or just wait and see. And she has that little sticky note. I remember I came home from prison, and I walked into her bedroom – she has a mirror in her bedroom – and she had the sticky note pasted on her mirror. And I knew I had forgotten about it by that time, because I sent it to her years before I came home. And now to see, not only now, but because the book is just, I won’t say it’s just, [but] the book, is just one of the many things that have made her proud, where I’ve fulfilled that promise. I hurt my mother a lot. I write a very long piece about my mother in this book, and me understanding the pain that I’ve caused her. But I also now understand I’ve also caused a lot of joy for her, you know, and thankfully she has all her mental faculties to appreciate it. But you know, in so many ways, my parents and my family, my brother, sister and my nephew, they were my reentry program. People talk about reentry, it wasn’t no program. I didn’t go to anybody’s program to make me better. And I’m not trying to discount the value of reentry programming. I’m saying for me, the reentry programming for me – and I understand it’s a privilege in saying this because not everyone has a stable family to come home to – I understand and acknowledge the privilege in that, in that blessing; they were my reentry program, not only during incarceration but definitely post-incarceration.

Joshua Hoe

To borrow something from one of my favorite television shows – you went through a lot as a kid. If you could go back and talk to a young Marlon, what would you tell him now, after you’ve been through this long journey and all the things that have happened?

Marlon Peterson

I would tell him that you don’t deserve any of the things that happened; what’s happened to you was wrong. And I think growing up as a child, I didn’t understand what was happening, that things that were happening, these things are wrong; these things should not be happening to me. I thought this is how it is, this is how it’s supposed to be, or in some ways I will put myself in the position of it was my fault. I shouldn’t have walked down that block. Or I shouldn’t have did that thing. I shouldn’t have went to that hallway, walked down that hallway in school, or you know, those sort of things. And I blamed myself for being harmed. One thing I would tell my younger self, I mean, the book opens up with me very literally saying Dear Marlon, me writing to myself, is that, you know, the things that happened to you are wrong. I think the value of understanding that something that happened was wrong, it gives you, at least it can allow you to speak about it, can allow you to, it can push you, to compel you to seek help. Because I didn’t think these things were wrong, I think it shouldn’t not be, couldn’t not be, because of the way I sort of experienced those moments when I was a young person as not necessarily being wrong and unfair. I just figured I should keep it to myself. It’s just what happens to everybody, so why should I talk about it? What’s gonna make me special, any different? And that hurt me a lot. And I just kept it to myself, and it showed up in different ways. So I would definitely tell a younger version of myself that I know what happened to you was wrong. And in the book, I’m literally open about my lips, right, having big black lips. And, you know, I use that – it was very real – where I was ashamed of it, it was also in so many ways, metaphorically, where I just felt like I needed to hide, right, the opening chapter is “Hide”, right? I think I would tell a younger version of myself that you shouldn’t have to hide anything about you, not your lips, not how smart you are, or whatever, that’s . . . or your talkativeness, don’t hide that. But those are the things that make you you, Marlon.

Joshua Hoe

A lot of our brothers and sisters come back from incarceration and try to publish books. Now that you are a successful published author, what advice would you give to them about publishing?

Marlon Peterson

Oh, first of all, this book – okay, I’ll say this – actually, somebody else I was having this conversation with last night who just came home not too long ago. Write, first of all write. Because some of the words or passages from this book were in so many ways written before I started writing this book. I have journals from inside but I also kept journaling after incarceration. So I had a lot of information to go back and look to and be like, how can I put this in and how to explain this a little bit better. So just write. That’s the first thing I’m going to say. I wrote a lot before this; I would write inside, I would interview other guys inside, that’s how I got better at the craft. And I came home, I would use this craft. I like to speak about issues of incarceration. I like to say I’m probably a writer first over anything else. So write. That’s the first thing I would do. The other thing is that I think – the publishing game, you know, there’s two options: you can publish it yourself, and you could, you know, seek a whole publishing setup. And I have a publisher, and all that, and editor, and all that sort of jazz. And those two options are available to you, you do your research and figure out what’s best, what best fits you. But it doesn’t matter which route you choose. If you’re not writing, like you’re just not actively writing things, whether you write them for public consumption, or you just write to keep to yourself or share to your friends and family. If you’re not writing now, that’s your practice. lf you’re not practicing now, don’t think that you could just write a book tomorrow, right? It takes a lot of practice. But if you’re a writer, and you’re someone who is formerly incarcerated or you’re incarcerated now, like the best advice I could tell you is to write right now, like it’s a double, that’s a double entendre. But right now, write now, because that’s the way that you get yourself ready for the long haul. I mean, I wrote a 200 and some odd page book. I’ve never written anything that long before. But I also say that I had so much – I have stacks of writings in my house, stacks of writings from incarceration and post-incarceration – that I was able to use as research and as my practice. So just like if you’re a ballplayer, you know what they tell you; you gotta stay in the gym.

Joshua Hoe

That’s true.

This year, I’m asking people if there are any criminal justice-related books they might recommend to others, aside from your own. Do you have any other favorites?

Marlon Peterson

Yeah, I’m looking at them now. So Mariame Kaba’s new book is one that you should definitely know; We Do This ‘Til We Free Us. I think that’s one really good book. I think I’m gonna shout out Reginald Dwayne Betts, who I’m gonna be in conversation with a bit later; he has two books. His most recent book is a book of poems called Felon, which I think you should check out, but also his previous one, which is Bastards of the Reagan Era, I think is another one you should check out, too. We all know there is a huge library of books out there. But I also want to say this, actually I want to rebut something I just said – I want to say that there aren’t enough of us writing these books. I want to say there aren’t enough of us who have experience, writing these books. And I’m talking about the whole gamut of people who’ve been incarcerated, not just the folks who have been unfairly convicted, innocent folks, but the folks who committed a crime and were convicted. I think those people, us, that’s me; we need to be writing these books, all of us need to be writing to the experience, because this is documentation of this atrocity in this country at this moment in time, when you have 2 million people in prisons; when your investment in prison is more bigger than your investment in anything in terms of social programming, or support for these communities. This is a flashpoint in human history. And we need to document this, and I think people who have had experience need to document, and particularly people who are currently incarcerated. I don’t know if the publishing game has gone to the place where it’s able to do that, where it’s open, and understands the importance of getting currently incarcerated authors on the books, right? Cause I’m an advocate for that, currently incarcerated authors on the books. But I think that’s what we need to go to. And I also encourage this part, right? People who are, who have had our experiences, currently or formerly incarcerated, to also look at how they can infiltrate other parts of the publishing industry, because not only writing a book, but I’ve learned, and I’m learning right now, but it’s also about like, there are gatekeepers, the gatekeepers who are in the publishing game, right. And a lot of them don’t understand us, and may say, Well, I don’t think you should talk about it like that. They don’t understand our experiences. I will also encourage people who want to be in the publishing, in the writing game, to also look at other ways you can infiltrate this publishing industry. As an editor, we need formerly incarcerated editors. We need formerly incarcerated editors. And that’s another place I think we can go and capture. That’s my advice. Try to see how you can be a formerly incarcerated editor.

Joshua Hoe

You’re famously a podcast host too. So I figure I’ll ask you if there’s anything you want to ask me this time.

Marlon Peterson

Definitely! Why haven’t you stopped Decarceration Nation? Why wouldn’t you stop this podcast? You’ve had about 100, over 100 episodes, right? 1

Joshua Hoe

Yeah, correct.

Marlon Peterson

Why haven’t you been like, well, I did 100 episodes, let me do something else now.

Joshua Hoe

I think mostly because there still seems to be interest, and there’s so many more people’s stories to tell. And, you know, people are putting out new . . . a lot of what I try to do is policy deep dives. And people are putting out new research all the time. And I want to get the education out there to folks so that they can speak back to the bad things that people are saying, the untrue things that people are saying, about why we should maintain the same thing we’ve been doing for the last 50 years. You know, the classic definition of insanity – continuing to do the same thing over and over and over, even though it’s failing. And so I think that’s really why I do it, it’s just to keep saying: here’s the news, but the news that they don’t usually print if that makes sense.

Marlon Peterson

You know, everything fit to be printed in The New York Times doesn’t get into The New York Times; you’re catching everything that really needs to be recorded, I guess. Can I just ask one real quick one? Sure. That, okay. I had debated this too, as a podcast. How do you feel about interviewing people who come to the criminal justice space in a different way? Like I think about the Koch brothers; how would you feel about interviewing one of the Koch brothers on Decarceration Nation? Do you feel like you want to give them that platform? Or are you journalistic in the endeavor?

Joshua Hoe

I actually have interviewed Mark Holden, one of their Senior VPs on my podcast, and it was . . . So much of the work that we try to do in legislatures is impossible to do without bipartisanship because red states aren’t going to move . . . blue policies aren’t going to move red states. So you got to have people on both sides. And so, I go along the line of, trying to work with everyone who’s trying to actually move the ball forward in our area, where they’re not trying to make systems bigger or worse. And even if they are, I’m not going to work with them on that stuff. But the stuff that we can work together on I’m going to try to get done. Because in the end result, what I care about is people coming home and people getting free. And so it’s not really necessarily as much about the other people, as it is getting things done, and getting information out there – for me. And I understand, I totally understand why other people don’t make that choice. And I certainly don’t blame them for that. But I’ll pretty much talk to anyone. And if someone is gonna start saying stuff that is problematic – hopefully, I checked them on that at the time. That’d be the way I probably look at it. I hope that makes sense.

I always ask the same last question, which is, what did I mess up? What questions should I have asked, but did not?

Marlon Peterson

You did pretty good, Josh, we did good. I was giving all the praise in the beginning. You’re obviously great at this. So I don’t think there’s anything you left out. I mean, we could stay here, obviously, and talk probably for another hour or two. So I mean, I can always come up with what’s another question you could ask. I don’t think that’s necessary. I think we covered bases. I like the fact that it was a layered conversation, that wasn’t just policy or criminal justice wonky, but you asked about . . . particularly I’m here now as an author; you asked questions that allowed me to elicit parts of my biography, of my life, that aren’t necessarily always attached to crime, to criminal justice sort of stuff. And I think that’s important. I think that’s super important. Because when we are in this world, whether in the policy space, when I’m in a policy hat space, what moves policy, ultimately, are the stories. That’s what ultimately moves policy, right? How you can get people to realize that something matters. And I think with the way you started off, with not so much about why I mattered, but more so about why understanding the depths of people matters.

Joshua Hoe

How can people best find your book?

Marlon Peterson

You can go to my website, marlonpeterson.com, and you’ll have all the ways in which you can purchase the book. So I’ll say you can start there. It’s available everywhere. Of course, I encourage you to buy from a local bookstore, and you know, indiebound, I-N-D-I-E-B-O-U-N-D, is one of the ways you can find out what local bookstores are near you, and if it’s there and available. And also I did the audiobook. So you can once again go on my website, and find out how to purchase an audiobook, and you can hear my voice reading Bird Uncaged: An Abolitionist’s Freedom Song.

Joshua Hoe

Thanks so much for doing this Marlon. I really appreciate it; it’s great to get to talk to you here.

Marlon Peterson

It finally happened.

Joshua Hoe

Thank you. Absolutely. Talk to you later, brother.

Marlon Peterson

Right. Goodbye.

Joshua Hoe

Now my take.

I have to say I’ve rarely read a more brave book than Marlon’s book; Marlon takes on strong topics like toxic masculinity, sexual assault, being raised male in a world that raises men poorly, and about feeling constantly vulnerable and constantly traumatized as a young African-American male in an often brutal country. He exposes himself, his weaknesses, his flaws and his powerful victories, all in order to let people really see how our systems of economics, education, religion, transportation, toxic masculinity, and our social safety nets frequently fail kids just trying to make it to adulthood alive. It takes an incredible amount of courage to put yourself out there like Marlon did. It shows how big his heart is, and how much he cares about making the world a better place. But I think it’s also important to remember that it isn’t just that it takes courage. We should also be thanking Marlon for putting himself and his story at risk in the public eye, and for being willing to relive that trauma publicly. Thank you Marlon Peterson.

As always, you can find the show notes and/or leave us a comment at DecarcerationNation.com.

If you want to support the podcast directly, you can do so at patreon.com/decarcerationnation; all proceeds will go to sponsoring our volunteers and supporting the podcast directly. For those of you who prefer to make a one-time donation, you can now go to our website and make your donation there. Thanks to all of you who have joined us from Patreon or made a donation.

You can also support us in non-monetary ways by leaving a five-star review on iTunes or by liking us on Stitcher or Spotify. Please be sure to add us on Instagram, Facebook, and Twitter and share our posts across your network.

Special thanks to Andrew Stein who does the podcast editing and post-production for me; to Ann Espo, who’s helping out with transcript editing and graphics for our website and Twitter; and to Alex Mayo, who helps with our website.

Also, thanks to my employer, Safe & Just Michigan, for helping to support the Decarceration Nation podcast. Thanks so much for listening to the Decarceration Nation podcast. See you next time.

Decarceration Nation is a podcast about radically re-imagining America’s criminal justice system. If you enjoy the podcast we hope you will subscribe and leave a rating or review on iTunes. We will try to answer all honest questions or comments that are left on this site. We hope fans will help support Decarceration Nation by supporting us from Patreon.