Joshua B. Hoe interviews Bruce Western and Emily Wang about COVID in prisons and jails.

Full Episode

My Guests Bruce Western and Emily Wang

Bruce Western is the Bryce Professor of Sociology and Social Justice and Co-Director of the Columbia Justice Lab, and the author of many important and influential books and studies about criminal justice this is also his second time on the podcast.

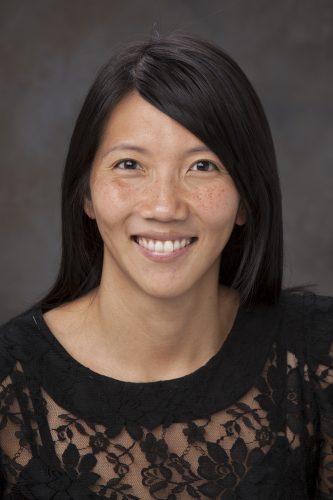

Emily Wang is an associate professor at the Yale School of Medicine and directs the new SEICHE Center for Health and Justice. The SEICHE Center is a collaboration between the Yale School of Medicine and Yale Law School working to stimulate community transformation by identifying the legal, policy, and practice levers that can improve the health of individuals and communities impacted by mass incarceration.

Emily also leads the Health Justice Lab research program, which receives National Institutes of Health funding to investigate how incarceration influences chronic health conditions, including cardiovascular disease, cancer, and opioid use disorder, and uses a participatory approach to study interventions that mitigate the impacts of incarceration.

Emily and Bruce were also co-authors with a team of other experts of the book “Decarcerating Correctional Facilities During COVID-19” published by the National Academies of Sciences and a recent White Paper called “Recommendations for Prioritization and Distribution of COVID-19 Vaccine in Prison and Jails.”

Notes From Episode 91 Bruce Western and Emily Wang

The Marshall Project has kept track of COVID in prisons and jails across the United States.

You can keep up with the numbers in Michigan on this MDOC page on Medium.

Here are the CDC recommendations for COVID.

And here is more from the National Academies of Sciences.

The American Medical Association has addressed COVID in carceral facilities as well.

The Prison Policy Initiative also keeps track of COVID in prisons and jails.

Emily mentioned this study about COVID in jail.

She also mentioned this study about the Cook County Jail.

The Lancet has this accounting for Decarceration as the result of COVID-19.

And here is more on the reproduction rates in jails.

The books my guests suggested this week were:

- The Chosen Ones: Black Men and the Politics Of Redemption by Nikki Jones

- Life and Death in Rikers Island by Homer Venters

Full Transcript

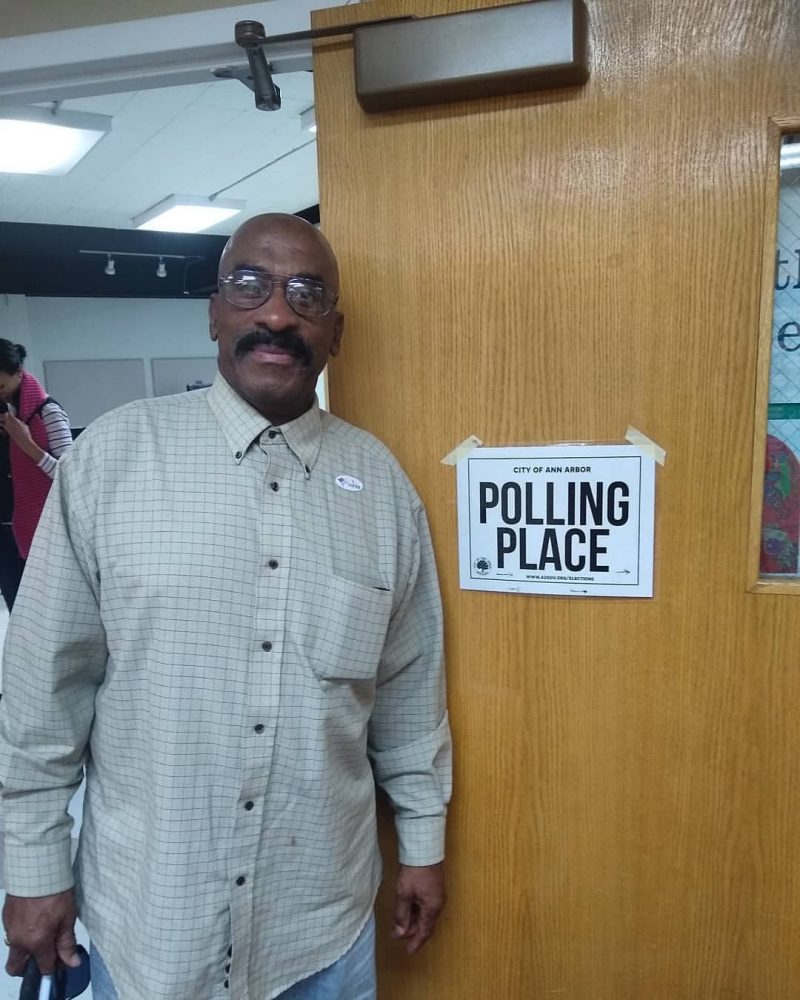

Joshua B. Hoe

Hello and welcome to Episode 91 of the DecarcerationNation podcast, a podcast about radically reimagining America’s criminal justice system – and a very happy Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Day 2021.

I’m Josh Hoe, and among other things, I’m formerly incarcerated; a freelance writer; a criminal justice reform advocate; and the author of the book Writing Your Own Best Story: Addiction and Living Hope.

This is our first episode of the fourth season of DecarcerationNation. I want to take the time to thank all of you for your support over the last three years. I’m very excited to be back and very excited to start up Season 4.

This week my interview is with Emily Wang and Bruce Western and we’ll be discussing COVID in prisons and jails.

Emily Wang is an Associate Professor at the Yale School of Medicine and directs the new SEICHE Center for Health and Justice. The SEICHE Center is a collaboration between the Yale School of Medicine and Yale Law School working to stimulate community transformation by identifying the legal, policy, and practice levers that can improve the health of individuals and communities impacted by mass incarceration. Emily also leads the Health Justice Lab research program, which receives National Institute of Health funding to investigate how incarceration influences chronic health conditions, including cardiovascular disease, cancer, and opioid use disorder, and uses a participatory approach to study interventions that mitigate the impacts of incarceration.

Bruce Western, our returning guest today, is a Professor of Sociology at Harvard University, a Visiting Professor at Columbia, and the author of many important and influential books on studies about criminal justice. And Emily and Bruce were also co-authors – with a team of other experts – of the book Decarcerating Correctional Facilities during COVID-19, published by the National Academy of Sciences; and a recent white paper called Recommendations for Prioritization and Distribution of COVID-19 Vaccines in Prisons and Jails.

Welcome to the DecarcerationNation podcast Bruce and Emily.

Joshua B. Hoe:

I always ask the same first question: How did both of you get from where you started out in life to where you found yourself working on the intersection between COVID-19 and prisons and jails? Bruce, you’ve been here before, so I’ll start with Emily.

Emily Wang:

Great, so where do you start, right?

If I looked at my younger self as a medical student, I probably wouldn’t have thought that I’d be a practicing physician, mostly doing research now at the intersections of criminal justice systems and health. I was fortunate, I guess, to say that I didn’t have a family member that was close to me, or a friend who had been incarcerated. And that was really by pure luck. As a medical student – I was at Duke University in Durham – and a girlfriend of mine was dating a guy who was running a prison education program, a college education program, in corrections. And in a very long conversation, I started learning about the deep racial disparities and the death penalty. I had studied the history of HIV in college, and not once, at least in my recollection, did we really start thinking about how the structures, the institutions and policies that dictate our criminal legal system, impact HIV. And so this really shook me to the core. During medical school – again, most medical schools, as you all may know, don’t have curricula on how to care for people that are incarcerated, [or] how to care for people who return home. And so I just cold wrote a few prisons in North Carolina, and ended up working in a women’s prison in Raleigh, and it was there that I saw young women my same age that very much had kind of different life courses, different life paths, but I could really relate to these young women, and I started understanding how our criminal legal system has such a strong bearing, plays such a strong role in the health of – especially young – women and men from certain communities and kind of my career turned from that.

Joshua B. Hoe:

And Bruce, what else can you tell us about your journey to this work?

Bruce Western:

I really started out as a poverty researcher in sociology, not a criminal justice person, living as an Australian in the United States in graduate school. The American penal system, just loomed as such an important focal point for understanding poverty in America. So fast forward several decades, and I was working on a re-entry study in Boston, and I was spending a lot of time with people who were leaving prison in Massachusetts and returning to neighborhoods in the Boston area. And it was really striking for me how people’s health problems affected their re-entry experience. I have one respondent – a woman who I got to know very well – she was in chronic pain throughout the first year of her release from prison and had many, many physical health problems that she was dealing with. And it completely overshadowed her experience of re-entry. And so I’ve become more and more interested in the intersection of health and incarceration, really, over the last seven or eight years. And then just in the very recent past, Emily and I had been working together on a variety of projects. And over the summer, or just before the summer, we got in a conversation about the health crisis that was just exploding in prisons and jails around the pandemic. And we talked about what we might do to help meet that challenge.

Joshua B. Hoe:

I wanted to start this season with COVID in prisons and jails, because as The Marshall Project estimated, at least 329,298 people in the correctional system have become infected with COVID since the start of the pandemic, with at least 2020 deaths. In my home state of Michigan, as of last night, we’ve lost 124 people. And 23,335 people have become infected in a system that has around 34,000 people in it. Emily, from a medical perspective, can you explain why you think this has happened? And why the response to date has been – I think there’s no other way to put it – why the response has been so ineffective?

Emily Wang:

Yeah, the numbers really are astounding. And I think – very much as you would indicate – from my clinical practices for the past decade of taking care of individuals as they return home from jails and prisons, and we see them within a week, two weeks post-release, and to see men and women return home from Corrections and describe the state of chaos and fear, during the COVID pandemic has been profound. I mean, you think I’ve heard it all and really, it’s just in a different state.

You know, part of what I think is important … I often think about the medical colleagues that work around me that haven’t stepped foot in prisons. I mean, I think some of it is predictable, right? If you look at past respiratory outbreaks, pandemics, prisons and jails often are places where diseases spread quite readily. And I think in this scenario, there’s a number of factors that have caused the increased vulnerability of people that are living in correctional systems, as well as working in correctional systems. And Bruce and I and our colleagues report on this in the Consensus Report within the National Academies report as Bruce referenced. To walk into some correctional facilities, it’s important to note that a good number are really overcrowded. We’ve had a state of mass incarceration of the past four decades, whereby many correctional facilities are over their stated built capacity. And that’s one piece of it. But it’s also important that even in facilities where there isn’t overcrowding, where people are packed in wall-to-wall living, double bunks in a gym, even if they are single-celled, there’s a lot of facilities where people spend much of their time in congregate settings, right? So you know, where they eat, where they shower, where they exercise. And so the ability to socially distance is virtually impossible. Other things that I think have placed people at increased risk are just the very fact that, what we do know about people that are incarcerated is that there’s higher rates of chronic conditions that put people at increased risk for COVID. And this of course, includes things like high blood pressure, as well as asthma. It also includes autoimmune conditions and conditions that attack the immune system. And so there are many conditions that people have that then are putting them at increased risk for COVID. But, I think one of the things that strikes me and much of what I spend my time thinking about is how differently-structured healthcare systems are behind bars. While there is access to health care, a constitutional guarantee, that access is so different than you might see in the community. So you know, for people who are incarcerated, if they’re having respiratory symptoms, sometimes it’s hard, nearly impossible, to get the attention of health care providers. One of the things that’s been really clear to us, in talking to physicians that practice behind bars, is that they’ve been unable to get tests at times in a timely fashion. And so, ordering tests, they’re deprioritized in terms of where they are in terms of the state’s public health infrastructure. And so the ability to get tests, the ability to get resources, the ability to even take care of people, patients who are incarcerated, is so defunded, and deeply siloed, from the rest of the public health infrastructure, that kind of as a whole what you’re seeing now is just this increased risk of dying behind bars, due to COVID, as well as increase in transmission. And so it’s a whole conglomerate of factors, I guess, that are causing this pandemic to really spread and be hot-spotted within correctional facilities.

Joshua B. Hoe

I definitely remember when I was inside that, for instance, you’d have one doctor who came in once a week and a couple of nurses and then the whole facility – 1000s of people – would basically run through that system. So it’s definitely not set up very well for a pandemic.

Bruce, from a policy perspective, what did politicians and Departments of Corrections get wrong at the beginning of the pandemic? And do you see any mistakes they’ve made since that time?

Bruce Western:

I think at the very outset – this builds on what Emily was saying – if we think about the American healthcare system, it’s this vast array of institutions of healthcare providers; a huge regulatory and oversight apparatus has been constructed to maintain medical standards. And the whole economic side of it, around billing and health insurance, and so on. It’s completely integrated into this system of oversight. So correctional health care, the way in which healthcare is delivered inside prisons and jails, it’s entirely separate, it has no connection to the US healthcare system. It’s not part of the same regulatory institutional financial framework that allows the American healthcare system, such as it is, to run from day to day. So the big mistake at the outset of the pandemic – because of this dramatic siloing of correctional health care from the rest of the US healthcare system – the prisons and jails were entirely left out of the public health discussion around pandemic preparedness. And as we’ve seen, and as you’re talking about in Michigan, prisons and jails have been leading hotspots, leading clusters for COVID. And yet, they were not systematically integrated into the public health plan. There wasn’t a plan for testing, there wasn’t a plan for implementing distancing and quarantining and, and so on. That was part of the broader approach to the response to the pandemic. And you know, thinking back to March and April, when the pandemic was just beginning to tear through Rikers Island Jail in New York City where I live. At that time, the jail was not, at the outset, integrated into pandemic preparedness, CDC didn’t produce guidelines for COVID in correctional settings until July, so the pandemic was already exploding at that time. At a more general level, I think part of what’s going on is that incarceration just creates these habits of dehumanization, that the people inside prisons and jails are regarded as less than fully human. They’re not part of our conversation about the welfare of the population. And so you know, there’s this myth that somehow these institutions, prisons and jails are isolated from the rest of society, and what happens there has no effect on the rest of society. That’s a product of that dehumanization, this very narrow view of what safety means. That’s a product of dehumanization, the idea that a pandemic could really fundamentally threaten community safety falls outside of how criminal justice policymakers think about safety. And so, the pandemic wasn’t taken seriously as a threat to safety. And I think that’s because of the way in which incarceration is really built on the dehumanization of the people who are confined.

Joshua B. Hoe:

And I think this will build on this a little bit. I know that usually, when we talk about pushback, when we talk about things like trying to deal with healthcare or things in prison because of COVID, a lot of times the pushback is that there’s a lot of people out here [in the free world] who are suffering from COVID, and they haven’t done anything wrong, etc.

So Emily, how much more dangerous is COVID in prisons and jails? And what is the risk of it coming back into our community as a result of ignoring it or not dealing with it in the correct way?

Emily Wang

Sure. So you know, one of the places where I would start is that early on in the pandemic, our team here at Yale had the opportunity to partner with researchers at Stanford, Professor Margaret Brandeau and her graduate student, Giovanni Malloy. And what we were able to do is get data from an anonymized, large urban jail and actually look at what is the spread of COVID-19, in this large urban jail, and found that the beginning of the pandemic and the first 223 days, I think, after the outbreak, what they found, what they were experiencing was that for every one person infected, eight other people were getting infected with COVID-19. And this is inclusive of people that work there, as well as those that are incarcerated there. So, you know, we’ve heard a lot about the basic reproduction ratio, which is kind of an epidemiologic measure of infectivity. And so one person infected eight others get infected. And that’s higher than cruise ships, that’s higher than at the peak of the pandemic in any community setting. And so while it’s true that this is just reflective of one jail, what I do feel confident in saying is that it’s extraordinarily high, and especially high in congregate settings in that large urban jail. And those conditions are likely similar, as you will find, to the other 5000 correctional facilities. And so it’s not to say that it’s reflective of all, but it certainly shows that we see prisons and jails as places where the Coronavirus is concentrated because of these very conditions. And it is much more dangerous in those settings. It’s also dangerous because of the policies that Bruce has explicated, which is that when people are incarcerated, they don’t have control over where they’re sleeping, how they’re showering, how they even get health care. Even the people that work inside don’t have control over how it is that they can actually get access to tests or vaccines. So in those ways, there’s real structural barriers for how you can actually manage COVID-19 in prisons and jails that’s just different than in the free world. Even in settings where the rates are high, that basic reproduction ratio or the effect of reproduction ratio is high, you still can make a choice. You still can access healthcare, you can get tests. So I’d say it’s differently dangerous in [because of] your inability to control your own risk behind bars.

Joshua B. Hoe

What about the two-way risk like government coming back into the community?

Emily Wang

Right. Undoubtedly, an important point is that people think of jails and prisons as out there – Oh, my gosh, what’s that? Oh, that’s a problem. But they’re quite porous, especially jails that people move in and out of. And so, the number – depending on who you’re counting and how you’re counting – but range as high as 10 million [who] move in and out of our whole correctional system each and every year. And then you have to think about all the other people that work within correctional systems, and the people that volunteer, the families that visit. And so there is a large community of individuals that moves in and out of prisons and jails, who are exposed to COVID. And so while I haven’t seen definitive studies, there is a study that was published in Health Affairs that showed that about 16% of community transmission in the state of Illinois could be associated with this throughput in and out of Cook County Jail. And so all this is to say is that what is happening in prisons and jails certainly affects what’s happening in the community, and vice versa, and that to think about them as totally different is just flawed.

Joshua B. Hoe:

One of the things that I heard pretty early on here in Michigan was that because of collective bargaining and unions, correctional officers didn’t have to get tested, maybe didn’t have to get vaccinated whenever the vaccine became available. And that seems like a pretty big problem to me, Bruce, what have been some of the problems that you’ve noticed, from looking at what people have been doing across the board in departments of corrections, while you were working on the book and the white paper?

Bruce Western:

The issues around staff have been really challenging. And on our National Academies panel, John Wetzel, as Secretary of Corrections in Pennsylvania was part of the panel and we met with correctional leaders as part of the work we did, and staff issues often came up as a big challenge in managing the pandemic. Number one, they’re massively at risk. And the data that we have shows that correctional staff have much higher COVID case rates than in the general population. They’re not as high as the COVID case rates for incarcerated people, but much higher than the general community. And part of the effect of this very hazardous working environment is the creation of staff shortages. People are absent because of illness. And that’s been a huge challenge for departments of correction. So implementing all of the guidance on how to try and manage the pandemic inside, with cohorting and quarantining, physical distancing, and wearing personal protective equipment, dispensing it and all of that, that becomes much more difficult when you’re understaffed, because people are getting sick. Another thing that came up – and this sounds similar to the issues you’re describing in Michigan – is staff compliance. And so, you know, wearing masks inside the facility, wearing protective equipment, and being diligent in following all the routines. You know, we heard from correctional leaders, that’s been challenging, as well. And candidly, we heard that oftentimes, incarcerated people were much more [compliant] than staff in following those sorts of rules. So I think there are just so many moving parts to managing the problem of the pandemic. The staffing is just one piece of it that goes to the physical plant of facilities, how they’re ventilated, how housing units are laid out, are they dormitory style? Can people be single-celled, which is such a multi-dimensional problem, but then there are a whole variety of issues connected.

Joshua B. Hoe:

And it’s not just a problem of how people get sick or if people get sick, but it’s also a problem of people dying.

I think in the book, you all mentioned a rate of up to four times that of the general population. Is that correct, Emily?

Emily Wang:

Yes, that’s right. It’s three times.

Joshua B. Hoe:

And one of the ways that you all suggested – I certainly said this early on – and I think most advocates have been suggesting since the beginning of the pandemic where we could have perhaps been more effective was decarceration strategies. What was the case from a public health perspective for decarceration? Emily?

Emily Wang:

Right, an important piece and again, one that we explored in this Consensus Report for the National Academies, was really looking at decarceration as an important tool among tools that could be used in correctional facilities. And the three of us have been discussing the unique conditions within corrections that for a variety of reasons that are both historic, and still yet very present. Correctional systems and their design; correctional systems and their overcrowding; correctional systems and how their healthcare systems are constituted, and what resources they have. They have been under-resourced and unable to actually manage a novel Coronavirus respiratory outbreak. And so, in that scenario, what I can say confidently is that decarceration permits correctional facilities – by releasing those who are at higher risk – to improve public health and also public safety that, as you’re saying, people are dying inside, right. And so this is a time to really think about how it is that you can depopulate correctional facilities to better be able to enforce the guidance that is evidence-based, which includes single-celling, so people sleep to themselves. Early on in the pandemic, I saw guidance guidelines that were coming down where, you could still double-cell, you can sleep toe-to-toe, well, that’s ridiculous, you obviously cannot, if your neighbor is coughing and your cellmate is coughing, and spreading COVID. That’s just ridiculous. Or, if you have so many people within a correctional system, and you’re unable to actually appropriately get the number of vaccines or appropriately be able to get number of tests to be able to appropriately manage populations by cohorting them, there’s just too many people inside, then of course, decarceration is an important tool, getting people out, or also reducing the number of people that go in, so that you’re better able to manage. I think an important piece that is close to my heart, especially as a practicing physician that takes care of people when they return, is that decarceration has to be also supported by robust supports, when people return home into the community. And so, we talked about this earlier, thinking about how it is that correctional systems are porous, people do come home. And they often can come home to settings, that of course, if without the supports of a safe place to stay, access to health care, access to testing, and then a way to feed themselves and have an income, then, of course, you augment the risk for further transmission into the community, thinking about their families in which they return. And so I think in those ways, decarceration can be safe, and it’s an important tool for correctional facilities, but it needs to also be done in partnership with local social service and health care systems in the community.

Joshua B. Hoe:

Bruce, I know a lot of people will hear that and say, oh, my goodness, how can you let people out of prison? But there is actually a fairly strong public policy case for decarceration as well. I know you’re familiar with the Sonja Starr/J.J. Prescott work. Can you talk a little bit more about the public policy case for decarceration in the time of this pandemic?

Bruce Western:

The pandemic has created such a massive social . . . and it’s run the economy into a ditch; we’ve had historic unemployment levels. For people who are already struggling economically, the pandemic has made life a lot harder. Problems like food insecurity have become widespread in the context of the pandemic. So there’s this massive social cost, and prisons and jails at the center of the pandemic, and they’re contributing to this cost the society as a whole is experiencing, that the pandemic is revealing. So many of the failures of our penal system – facilities [that] are old and poorly designed, they’re often overcrowded. People who are incarcerated often have serious health problems that are not being dealt with. And so all of these vulnerabilities have just been revealed by the pandemic. So the policy case, I think, for decarceration – by relieving the pressure on the institutions, getting people who are at very high risk, who are currently incarcerated out of these institutions, which are utterly toxic right now because of infectious disease – that will not only have benefits for them, but the benefits will redound to the broader society. You know that the pandemic is kind of an ethical litmus test, because it doesn’t respect. The artificial distinctions that we’ve created between victim and offender and guilty people, and innocent people, all our fates are tied together by the pandemic, and the well-being of the most vulnerable people in society is intimately connected to the well-being of society as a whole. And so I think decarceration in this context is vital for the safety and security for the entire society. And I think if we can make progress on this, if we can get this right, we’ll also be much better prepared for the next pandemic, which seems inevitable as prisons in jails have always been centers of infectious disease. And I think we’re always waiting for the next pandemic, and if we can, if we can make progress on policies for decarceration, that’s going to help preparedness and it’s going to reduce the toxicity of the penal system in our society more generally.

Joshua B. Hoe:

I think some people when they hear this will say, yeah, sure, we’re all tied together, and this is a danger and all this kind of stuff. But do you perhaps save people who are incarcerated from getting infected or dying from COVID, but also potentially create problems with recidivism? I know there’s a decent amount of research that rebuts this. Do you have any thoughts about the public safety part of the case?

Bruce Western:

I think Emily put her finger on it when she said that any strategy for decarceration has to have re-entry as a key component and the kinds of things that are important in a pandemic also make a lot of sense. For safe and socially integrative re-entry policy, particularly I think, things like continuity of health care. And having health care coverage and providers ready and waiting in the community for when people are released. Security of housing is super important. And I think particularly in pandemic conditions, if there are ways to house people coming out in private households, where they can isolate themselves in a socially supportive setting, that’s really helpful. And that partly means supporting the families of those who are coming home and helping to alleviate the strains on them. If they’re opening their homes to loved ones who are coming out from incarceration. And the third thing is income support. There’s just so much material hardship, immediately after incarceration, meeting basic needs, for things like food and shelter, it’s just fundamental to reintegrating in a safe way, in a way that supports public safety. So my view is that we can get there, we can get to decarceration on a significant scale, if we’re properly prepared to support people when they come home. I think that’s probably the crux of the next question.

Joshua B. Hoe

Either one of you can take a swing at this, but it seems like you’re suggesting – and I obviously agree with you – that we need better health care, we need better support for when people come back and re-entry, we need more decarceration, we need all these things.

But what we’re lacking, it seems, in a lot of places, is political will. There’s certainly some governors who have stepped up, but quite a few of them have quite gone the other way. So do you – after you’ve been doing the circuit on this stuff – do you have any thoughts on how we’re going to get people to where they should be, from an ethical perspective, and also from a public safety perspective, so that some of these changes can happen? We’re certainly not seeing widespread decarceration or anything else across the country, despite the incredible cost so far in prisons.

Bruce Western:

It’s interesting, I think, that there are a lot of signs that the larger criminal justice reform conversation was shifting and becoming more ambitious. Drug policy reform caught fire across the country, and I think a new kind of national consensus is forming around that. The challenge is changing our public policy response to people who have been convicted of violence. I think a public conversation was opening up on that front, and we’re now sensitized to the medical vulnerability, the health vulnerability of people who are incarcerated. So I think all of that was happening when COVID came along, and then opposition to decarceration. Any reform efforts, is also gathering momentum And I think this is our challenge, figuring out how to meet this opposition, which is often very well-organized, often centered in law enforcement, and among prosecutors, even though public sentiment is supportive of a much more rehabilitative, socially-integrated approach to people who have come into conflict with the law, and I think part of the answer has to be greater organization on the reform side; and more community organization, more community voice, in meeting the opponents of a more humane response to harm, and the tangled mess of problems of racism and health and poverty, that all just concentrates in the criminal justice system.

Joshua B. Hoe:

Emily, did you have any thoughts?

Emily Wang:

It’s interesting … I’d say – especially during the summer when we were working through this consensus report and looking at the numbers – it looks like actually the number of people held in prisons and jails went down by more than 20% right? And then when we dug in a little deeper, we found that there’s real differences between jails, there’s far more people that were released from jails and prisons. I just misstated. By 10%, but in jails it was about 20%. And then state prisons are about 5%. And one of the things that we noted was that it was a real passive kind of de-population; the courts closed; police just stopped arresting people; our country shut down in certain ways. But what I did find interesting was that even when there was the political will, even when people in executive branches and governors would step out and state that there was the need to release people that were high-risk, that oftentimes our bureaucracies for compassionate release, medical release, our ability to respond to pandemics was really stymied at the level of how it is that you get a person released on medical parole or compassionate release or anything that would enable the appropriate public health levers to be enacted to better protect those that are incarcerated and those that work there. And to me, that’s also part of the story here. It’s not just the deep dehumanization of people that are incarcerated, or an unwillingness to go there. At times, people, governors were [supportive], and we still couldn’t get people out and home and safe. And so, to me, that’s a lot of the work that has to come now is interrogating, why is it and what is it that needs to happen so that now, [while] we’re still in the middle of a large-scale outbreak, and then also for future pandemics? What needs to be happening to change those policies? And those are oftentimes legislative actions or even just practice changes that consider the ways that people can be released, how courts operate, how police and parole boards operate, but also how the health system operates, how the housing is more inclusive of people that have criminal records, how it is that we can more quickly provide income supports to those who are returning home.

Joshua B. Hoe:

I’ll all admit to some frustration after eight or nine months of pushing for these changes.

I’ve reached the place in my own advocacy, where I’m profoundly cynical about most of these things happening and at the level necessary to seriously lower the risks of death. You recently co-authored a white paper about vaccinations. I’ll start with Emily; should people in prisons be prioritized at a high level? The same [level] as, say, health workers? How should we be prioritizing people for the vaccine who are incarcerated?

Emily Wang:

My short answer is, yes, they should be highly prioritized. And, for me, and looking over the guidance of the board, over the summer, the National Academies also convened a group of experts that came up with a prioritization scheme based on the evidence, and based on the science, and based on an equity lens of who ought to be getting vaccinated, and in what priority. And given the increased risk of transmission, but in particular, the increased risk of death and dying and suffering from corrections, that consensus report came down and said that people who are incarcerated – because there’s increased risk, because they’re unable to navigate their own health or or mitigate their risks, compared to those in the general population – ought to be prioritized. And even what they said was that, in each category, so in that report, healthcare workers, let’s say, were at the top of that list, that correctional health care workers ought to then also be at the top of the list. The next on their list were people with chronic health conditions, those that were older, again, those people that are incarcerated that met those priorities ought to go in that round. And then at large in the second round, people that were incarcerated, all people that are incarcerated ought to go. So they’re really prioritized at the whole ecosystem of corrections, those at work, and those that are incarcerated ought to be prioritized. And it just makes sense. That’s where we have massive outbreaks, higher rates of death, people placed at increased risk within corrections, and so vaccines ought to be distributed there first, so they are in certain states and then in other states, of course, because the states can decide their own prioritization schemes, [corrections] are either not included in the plans or are deprioritized.

Joshua B. Hoe:

I know we’ve recently seen pushback in a number of states to vaccine prioritization. Governor Polis in Colorado, for instance, discarded the recommendations of experts and downgraded providing incarcerated people access to the vaccine, multiple different states have different schemes. In Michigan certain people are prioritized in Phase One, the bulk are in Phase Two, and in some states, they’re just not prioritized at all. My understanding is that Governor Cuomo has refused to prioritize folks.What are your thoughts about this Bruce?

Bruce Western:

I think that if you’re guided by evidence, the health argument seems unassailable. There’s no reason to differentiate the priority of correctional officers from the priority of incarcerated people; incarcerated people should have exactly the same priority as the staff of prisons and jails. People are equally exposed, and the ramifications of both getting sick and transmitting the virus to others [are the same]. Governor Cuomo has held himself out as taking an evidence-based public health approach. And the only reason I can see that you would distinguish incarcerated people from prison and jail staff is because you’re still in the grip of an ideology of dehumanization in which incarcerated people are less deserving. But this carries enormous risk. And I think now is the time for an evidence-based public health policy. And if you believe in such a policy, then incarcerated people should have equal priority.

Joshua B. Hoe:

Emily, I think a lot of incarcerated people have a lot of trust issues with health care and with departments of corrections. They’re also highly suspicious of vaccines. If you could go inside as a medical person who cares about these issues and talk to folks in prison, what would you tell them about vaccination?

Emily Wang:

Yes, there’s a lot of mistrust issues; the health system and health care providers have created systems that are discriminatory, that are off-putting, and really at times have diminished the health of people who are incarcerated. And oftentimes the conversation is “they’re so mistrustful and how can they be that way?” That is strategic and life-preserving to be mistrustful, so good for you. But what I would say to this, to my patients who are coming home from corrections, and also to those that are inside, the concerns that I’ve heard, I think are important ones, we all have these concerns, and some of the things I would say is that, to start, people have said, you know, like, oh, they’ve hustled on up, right? Like, how could they possibly have created a vaccine this darn quickly? And it is true, that the vaccines have been tested quicker. But the science behind these new vaccines has been going on actually for decades. And when you see things called like, Operation Warp Speed, what’s happened is that all of a sudden, instead of it being like a rush, job, quick science, all we’ve done is said, every person, all the millions of scientists that have put their brains around this issue, now we’re going to be working on it for 24 hours a day. And the federal government did invest a ton of resources into studying it quicker. And so it’s not that the quality of the studies are worse, it’s just that we’ve put in a lot more resources to study it. So these vaccines are not a rush job. And the second thing I would say is that, I’ve heard a lot of my patients be concerned that they’re inserting someone’s DNA. And there’s no such thing. There’s no insertion of DNA. These are messenger RNA viruses, vaccines that are not a piece of anyone’s DNA. It’s just like a code book that’s going to tell your own immune system how to fight against the Coronavirus; that, in fact, this vaccine is even more effective than I might have imagined at preventing severe illness and preventing death. And something that I would say is that they have every right to be mistrustful, every right to ask questions, and every right to demand that there would be kind of this forum and place to really look at the vaccines they’re getting asked the questions they want, and then make certain that they have the aftercare. Another question that I’ve gotten a bunch from patients is, what are the side effects – you’ve heard about it – allergies, and even anaphylaxis. And I think it’s important to note that, you know, of the millions of doses that have come forward so far – there’s a recent report just that came out this week- 21 people have had anaphylaxis, no one died, not a single person has died. These are all people that had allergies beforehand. And what’s important to note is that you should be watched, probably for about 30 minutes after getting the vaccine. And so these are the things that if you have questions you should ask; insist that you have a safe place for someone to monitor you before getting the vaccine, I think are all really important places. But to me, these are core questions that, before you get any vaccine, you should really know the safety and the kind of effectiveness of this. And this is a safe vaccine that’s been developed over decades, tested quickly, because we’ve pushed our national resources into it. And the ways to protect your own safety, is to ask a ton of questions and to make certain that someone’s watching you for 30 minutes after you get it.

Joshua B. Hoe:

What a really great and informative discussion this has been.

This year, I’m asking people if there are any criminal justice related books that they might recommend to others, if either of you have any favorites.

Bruce Western:

Yeah, there are a couple of books that I’ve been really impressed with lately. Nikki Jones’ book, The Chosen Ones, Nikki just won the American Society for Criminology Book Award. [It’s] just a beautiful ethnography of men who have been incarcerated in the Bay Area and are working as violence interrupters. Dave Harding and Jeff Marinoff and their colleagues have a great book on re-entry, On the Outside. And so both of those books, The Chosen Ones and On the Outside are terrific.

Joshua B. Hoe:

Emily, did you have any?

Emily Wang:

You know, I have read Nikki Jones’ book, and I think that’s a great recommendation as well. I recently just finished Homer Venters’ book, [Life and Death in Rikers Island]. And that [book] – especially for folks that don’t have a sense of what it feels like, to kind of walk through the healthcare system behind bars, he [Venters] used to be the Medical Director of Care within Rikers – I think was pretty illuminating as well.

Joshua B. Hoe:

I always ask the same last question: What did I mess up? What questions should I have asked but did not?

Bruce Western:

You know I think we covered everything. I regret missing Emily’s audio over the last 15 minutes. But I feel like we covered everything,

Joshua B. Hoe: Emily?

Emily Wang:

Great. Yeah, I don’t have anything else to say.

Joshua B. Hoe:

Great. Well, I want to thank both of y’all for doing this and for helping us start out the season on a really important note. So thank you for being here.

Bruce Western: Thanks, Josh.

Emily Wang: Thank you!

Joshua B. Hoe: Okay, now, my take.

When we take away people’s rights, and the ability for them to take care of themselves, we have to take responsibility for their care. We are dramatically failing in our responsibilities to take care of people in our prisons and jails. During this pandemic, incarcerated people are getting infected and are dying at a rate that is much higher than the rate out here in the free world. Health care is worse for them. And it is impossible for people in our facilities to socially distance and protect themselves. When people do get out, there’s no continuity of care or social support. So far, after nine months, most of our elected officials are either too stressed or too scared of the political consequences to either decarcerate or to provide priority access to the vaccine for our incarcerated populations. Meanwhile, people continue to die and none of them, not a single one, was sentenced to die from COVID. Nobody is going to help them if we don’t get involved in trying to make sure our politicians know, we need to help our incarcerated brothers and sisters. Saving lives is going to be on us. And the longer this goes on, the more people die. We absolutely must do whatever we can to make sure vaccines get to the people who want them in our facilities as quickly as possible, and decarceration happens whenever and wherever possible. Please let your governor and legislators know that they need to prioritize incarcerated people for getting access to the vaccine as soon as humanly possible. This is supported by the CDC, the National Academies of Sciences and many other experts. If we believe in evidence-based and science-based reform, and we want to save lives, we need to insist that every incarcerated person and every correctional officer gets vaccinated as soon as humanly possible.

As always, you can find the show notes and/or leave us a comment at DecarcerationNation.com.

If you want to support the podcast directly, you can do so at patreon.com/decarcerationnation. All proceeds will go to sponsoring our volunteers and supporting the podcast directly. For those of you who prefer to make a one-time donation, you can now go to our website and make a one-time donation there. You can also support us in non-monetary ways by leaving a five-star review on iTunes or by liking us on Stitcher or Spotify.

Special thanks to Andrew Stein who does the editing and post production for me, and to Ann Espo, who helps with our transcripts and graphics. Thanks also to Alex Mayo, who’s helping to run our website. Make sure to follow us on Twitter, Instagram and Facebook, and share our posts across your networks. Finally, thanks to my employer, Safe and Just Michigan, for helping to support the DecarcerationNation podcast. Thanks so much for listening to DecarcerationNation. See you next time.

Decarceration Nation is a podcast about radically re-imagining America’s criminal justice system. If you enjoy the podcast we hope you will subscribe and leave a rating or review on iTunes. We will try to answer all honest questions or comments that are left on this site. We hope fans will help support Decarceration Nation by supporting us from Patreon.