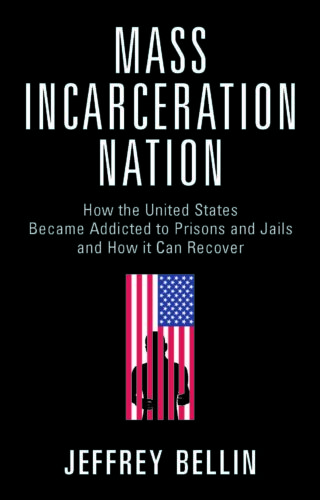

Joshua B. Hoe interviews Jeffrey Bellin about his book “Mass Incarceration Nation: How the United States Became Addicted to Prisons and Jails and How it can Recover”

Full Episode

My Guest – Jeffrey Bellin

Jeffrey Bellin served as a prosecutor with the United States Attorney’s Office in Washington DC and practiced with the San Diego office of Latham and Watkins. Mr. Bellin is currently the Mills E. Godwin Jr. Professor at William & Mary Law School. His book is Mass Incarceration Nation: How the United States Became Addicted to Prisons and Jails and How it can Recover.

Watch the Interview on YouTube

You can watch Episode 137 of the Decarceration Nation Podcast on our YouTube channel.

Notes From Episode 137

The books that Jeffrey Bellin suggested were:

Locking Up Our Own: Crime and Punishment in Black America, by James Forman Jr.

Ghettoside: A True Story of Murder in America by Jill Leovy

Full Transcript

Josh Hoe

Hello and welcome to Episode 137 of the Decarceration Nation podcast, a podcast about radically reimagining America’s criminal justice system.

I’m Josh Hoe, and among other things, I’m formerly incarcerated; a freelance writer; a criminal justice reform advocate; a policy analyst; and the author of the book Writing Your Own Best Story: Addiction and Living Hope.

Today’s episode is my interview with Professor Jeffrey Bellin, about his book Mass Incarceration Nation: How the United States Became Addicted to Prisons and Jails and How it Can Recover. Jeffrey Bellin served as a prosecutor with the United States Attorney’s office in Washington DC and practiced with the San Diego Office of Latham & Watkins. Mr. Bellin is currently the Mills E. Godwin Jr. Professor of Law at William & Mary Law School. His new book is Mass Incarceration Nation: How the United States Became Addicted to Prisons and Jails and How it Can Recover. Welcome to the DecarcerationNation podcast Professor Bellin.

Jeffrey Bellin

Thanks, thanks for having me.

Josh Hoe

My pleasure. I always ask the same first question. How did you get from wherever you started in life, to becoming a federal prosecutor teaching law at William & Mary, and in particular, how did you go from being a prosecutor to writing a book about ending mass incarceration?

Jeffrey Bellin

Yeah, wow. That’s a big question. And it’s something of a long and circuitous story. But I’ll give you the highlights. Because I think it’s the right question to ask. Honestly, if you’re thinking, why should we listen to you? That’s a good question. I’ll say it started with, I went to law school because I was interested in criminal justice policy. And I got a federal clerkship out of law school, because I had done well, for actually Merrick Garland, who everyone knows now; he was a judge at the time. And so I clerked for him in Washington, DC. And I had this thought that if I was going to speak about criminal justice policy, I needed to know what I was talking about. And the way to get some expertise was to work in it in some capacity. And I would have been happy to be a defense attorney or prosecutor or, in any way, to get into this system and see what was going on. What happened, or the job I was able to get was a job at the US Attorney’s office in Washington, DC. And you’re right [it was] a federal job. But this is unusual because there’s no state in DC. So the office there does what a DA’s office would do in other jurisdictions [and it] was actually a really good way to see what the reality of American criminal justice was like. And then from there, life intervened, and I ended up going out to California. And actually got to add another job at the California Courts of Appeal, working mostly writing criminal cases. And so that was actually really important because then I saw both a different perspective, the court perspective, and also a different state; California is very different from DC. And so I did that job for a while. And then finally, I realized that none of these jobs set you up to talk about policy. When I talked about policy to people that I was working with, they would just say, What are you talking about? just do your job. And so I realized I had to find some other lever, [and I] was able to get into teaching and started actually at SMU in Dallas. And that was just another way, I got some sense of Texas criminal justice there, talking with students and practitioners in that area, and finally moved up here to William & Mary. And when I was here, I felt like the world wasn’t talking enough about this topic, the topic of my book, so I started teaching a seminar called Mass Incarceration. So a mass incarceration seminar to students, and that helped give me a bigger-picture perspective. I was digging into all the research, and the numbers and the data, like the overarching picture, because I had a sense of how it worked on the ground and in a couple of different places. But I didn’t know the big-picture story as well. So I taught that seminar for a couple of years, I started doing research, thinking, I’m gonna write a book about this. By the time the book was done, people had learned about mass incarceration, there were other books. And so I was able to kind of lean into that as well. And then finally, was able to write the book I wanted to write, which was, even though there have been other books on mass incarceration, I felt like I had this unique perspective of kind of being in the trenches of it in different areas, and then combining that with an overview that you get from being a researcher. And I tried to write it in a really accessible way. My thought was, I want to explain mass incarceration as a tool to change, you know, you need to understand it to change it. And I wanted to explain it in a sophisticated way that was accessible to any audience. And that was what brought me to writing the book.

Josh Hoe

Oddly enough, you’re actually the third guest I’ve had on the podcast who clerked for Merrick Garland. Is there anything you can share with our audience about your experiences with Mr. Garland? And how hard do you suspect it must be? For him navigating questions like how to proceed with investigations on improper use of classified documents involving current and former presidents?

Jeffrey Bellin

Yeah, well, I’ll tell you one story, because I tell this to students all the time, it was actually very valuable. It’s interesting. So people might not know this, I didn’t know this, I didn’t have any lawyers in my family. But when I went into law school, kind of a path, if you do really well, in law school, you can get a clerkship, it’s a one-year position with a judge. And you know, the better you do, the more prominent the judge you can get your job with. And so I was really blessed to get this job with even then a very distinguished judge on the DC Circuit. And you know, at the time, he had already done things like prosecuted Ted Kaczynski, the Unabomber, and things like that. So he was kind of a really well-known figure, both as a judge and for his former career at the DOJ. And the thing about working for him was, he stressed [that] we do things the right way. So we’re going to do all the work it takes, we’re going to dig into the cases. And then we’re going to apply the law and the facts, just how people want the judge to be behaving, that’s what he was doing. It was doing everything the right way and wasn’t cutting any corners. And then I got into the US Attorney’s Office in DC. And there were other attorneys like that, a couple of other examples of people I worked with, who were really professional and thought about the right things, and were doing things the right way. But there were a lot of people out there who were not doing that. They were cutting corners, they weren’t thoughtful about what they were doing. They were doing things for the wrong reasons. And I always say that was very helpful for me as a young attorney, to have first encountered people like Merrick Garland, who were doing it the right way. So that when I later encountered people that were not doing things the right way, I didn’t fall for [it] when they would say, Well, everyone does it this way, or this is how you have to do it. This is the way it’s always done. I had a sense that no, it’s not how it’s always done. There’s kind of the right way you follow the discovery rules, you know, you dismiss the cases when you don’t have enough evidence like these are the right things to do. And even though I don’t agree with him about everything, that mindset of we do things for the right reason, stuck with me. And you know, hopefully, I would have had it anyway. But it was helpful to know that there are people who have succeeded in the profession, who weren’t cutting corners and weren’t sloppy. And then your second question, I mean, it’s, he’s got a very difficult job, I get asked that a lot. And he’s got a very difficult job. There’s few people that I would trust with that job as much as I trust him with it.

Josh Hoe

You make an early statement, in the introduction of the book, you say, politicians claim to be trying to solve the problem of crime, the critical flaw in the last 50 years of tough-on-crime policies is that this never works. Could you discuss this critical flaw in a bit more depth? What is wrong with the assumptions behind tough-on-crime policies and politics?

Jeffrey Bellin

Yeah, sure. It’s, and I think this is a critical point, one of the things I saw firsthand in practice, and then also, you can see in the data. So one of the things I stress is that if you look at the numbers, you’ll see that there’s a lot of fall off between the amount of crime that occurs in a jurisdiction, and then the amount of crime that’s reported, and then the amount of arrests that fall out of those reports, and the amount of people that are prosecuted, the amount of people that end up going to prison. And so, you know, prosecution can say, Well, I’m gonna get tough, or the legislature can say, I’m going to get tough on say, carjacking or something, some crime that people are excited about. And the way we’re going to get tough on it, is we’re going to send people to prison for 20 years, mandatory minimum 20 years for anyone that gets caught carjacking. And so in theory, what they think – and you can see this if you read, and this is part of the story that I tell when legislators were passing these tougher laws, that’s what they were saying. They weren’t saying we’re gonna pass a tough law on heroin sales, or gun possession because we want to catch a lot of people and put them in prison. They were saying we’re gonna pass these tough laws to make people stop. So no one’s gonna deal heroin, once they see how strict the laws are, no one’s gonna carry a gun around when they see the mandatory minimum for federal gun possession, and no one’s gonna do any carjacking once you get a 20-year mandatory minimum. And it just doesn’t work like that. Because a lot of these crimes aren’t being reported. If you think of heroin dealing, how many heroin deals are not reported? And then that spans everything I talked about in the book, you know, the very low reporting rates for almost all crimes, it’s actually two that are highly reported. And they are the exceptions, car theft because people have to get their insurance or get the police to stop bugging them about their car, that’s not their car anymore. And then homicide for obvious reasons. But other than that, you know, it’s less than 50% reported and some other crimes are much less reported. And so the crimes aren’t even getting to the police’s attention, and then the police are making arrests in only, you know, again, for homicide, it’s like 60% and then goes down from there. So they’re making arrests in a very low percentage of cases. And then from the arrests, a lot of those cases are falling out of this system at various points, and that’s something that I saw firsthand as a prosecutor. And so like the amount of these cases that result in someone actually getting the mandatory sentence that was, you know, passed with all this hoopla, it’s a very small percentage. So I’ve got this figure in there that I put together from cities’ robbery prosecutions, and for every 100 robberies, there’s five people, maybe going to prison. And so what’s happening is, we’re not going to be able to stop robbery with a really tough sentence, because the people that are committing robbery, you know, even if they’re just thinking rationally about it – and there’s all sorts of other stuff going on – but they’re not going to think they’re going to get the sentence, they’re going to think they’re going to be one of the other 95 circumstances where it’s not going to happen. So even if you have this kind of naive assumption that everyone’s [is] understanding what the laws are, and is going to react to the incentives you create, we can’t get people to stop committing crime, by making the punishment harsher. All we can do is increase slightly the small subset of people who we’re catching, and then put them in prison for a really long time. And that’s kind of what happened, you know, over a broad scale. We increased slightly the pool, not slightly, but slightly in each place, and then spread over years and years and places, you know, millions of people that created a giant number of people in prison, but we were still only catching a small percentage. And so it just doesn’t work. And all the studies show that severe sentences don’t deter crime. And so to the extent that that’s what the politicians were selling, it never worked.

Josh Hoe

And at the same time, you have people like former Attorney General Bill Barr, and folks like the Manhattan Institute, who are claiming that what America has right now isn’t a mass incarceration problem. It’s an under-incarceration problem, which, obviously, to someone like me sounds a little bit wild. But what drove you, given your background, to take on this topic? And why are they wrong?

Jeffrey Bellin

Yeah, and actually, that’s a great question again. So yes,you’ve asked three questions. Two of them, I’ve said already, are great. One of my frustrations in this space is there’s a lot of people who are talking to people that already agree with them. And if you really want to make any progress, you’ve got to get people who don’t already agree with you to see – they’re not going to come around entirely – but to see the points that you’re making. And so a lot of times when I push my students on these questions, that’s the kind of thing I say, like, here’s what someone else is saying, here’s how someone’s going to disagree with you, what’s your response? And we can’t just ignore the response, because a lot of people have these reactions. And that’s part of why I wrote the book, it’s supposed to reach across audiences, not just for people that already agree about mass incarceration, but to convince people that don’t agree. And importantly, like you said, a lot of the people that don’t agree that mass incarceration is a big problem, are people that hold the levers of power, like Bill Barr who was the former Attorney General. And so, you know, we have to think about what are they going to say? And when you get this before a congressperson, what are the people, their aides, and things going to say, when it gets in front of them? And that’s one of the things they’re going to say that like, oh, well, really what’s going on is we’re not catching people we need to catch more people. And so you know, this requires a book, The answer requires a book. And one part of the book that I talked about is, a lot of what goes on is we’ll point to something, so say, homicides, and will say like, oh, homicides have increased, or homicides are a real problem. And yes, they are, we have to own that. That’s a real problem. And society has to respond to the problem of homicides. But then that doesn’t mean we switch, and now we’re going to put drug dealers in prison for 20 years. And now we’re going to put people walking around with guns in prison for, you know, five-year mandatory minimums. There’s this kind of switch that goes on from like, well, here’s the problem. We’re trying to address homicides. And now we’re going to, you know, go after drunk drivers. And that’s kind of what happened with mass incarceration. As we started out, there was actually a spike in homicides. And the American people reacted to this idea that we need to be more tough and more severe, because it seemed like crime was spiraling, and the government wasn’t responding well to it. And for a while, that’s what the reaction of mass incarceration looked like. But then when homicide went back down, and it went down tremendously, and not because of anything, it just kind of ebbs and flows. But when it went back down, the severity stayed, and we could just turn the severity on everything. And we turned it on drunk driving and domestic violence and gun possession, and assaults and drugs and all these things. We started treating them more severely, and these weren’t a reaction to these other things. And so, you know, to me, it’s not an answer to say, Okay, we’re not catching enough people committing homicide. So let’s put everyone that’s selling marijuana in prison. These things don’t match up and there’s a lot of this slippage that goes on. And so then the question becomes, you know, what do we do about homicide? And again, you can see that the answer is not going to be well, the way to reduce homicide is to make the punishment more severe. Because that’s not the problem. We don’t have a problem with the punishment not being severe enough, we have a problem with catching people. And really what we care about is preventing homicides in the first place. And so that’s what we’re trying to address. And that’s what you know, Bill Barr wants to address, we want to have less violent crime. We want to have less homicides. And I think everyone shares that goal, so we need to think about how we achieve that goal. And a lot of what I’m doing in the book is pointing out that well, often people will say the way to achieve that goal is to put people in prison for longer. There’s a tremendous mismatch like there’s no evidence that that is actually the way to address homicide. You could see with homicide, clearly, because we already put people in prison for a very long time for homicide, there’s no one saying I’m going to commit a homicide because the punishment is so light, right? There’s just not and that’s true for all the really serious crimes that we care about. No one is doing them because the punishment is too low, or because they think there’s not going to be a mandatory sentence at the end of it – to the extent people are thinking rationally. And mostly that’s not the case when they’re committing these kinds of crimes, but to the extent they are, the problem would be that they’re not being caught. And so one of the things I say in the book is we need to take the energy we’ve focused on misdemeanor cases, parole revocations, and drug crimes, and shift that to the things we actually care about, like homicides. And then on the other hand, reformers also have to be thinking about how do we reduce the violent crime, because A, it’s important to do that on its own terms, but B, you’re not going to be able to get very far with any kind of reforms, if the politicians are able to do this trick where they’ll say, oh, homicides are up. So we can’t give an inch in any space.

Josh Hoe

So another kind of spine argument or an argument that underlies I think, all the arguments you make in the book, it’s this notion that the system should be more about finding justice and less about enforcing laws. Can you talk about this distinction that you make between the justice system and the legal system a bit more?

Jeffrey Bellin

Yeah, thanks, and I’m smiling. Because you’ve actually read the book, which makes me very happy. It’s always great when you’re getting interviewed by someone who’s actually read your book. Well, it really makes such a difference when you’re answering questions if the person is actually engaged with the material. And you’re right, this is a key theme of what I put forward in the book and runs through kind of everything I talk about. And so the framing of the book is, we didn’t use to have mass incarceration, this is a new thing that started in the late 1970s, it took a while to really become mass incarceration. But in the 1970s, kind of the way the system was set up was really like the criminal courts were a forum for resolving disputes that had to be somewhere like a criminal court. And so, you know, you think of it like a family member is murdered or shot, and the government has to react in some way, they can’t just say oh well, figure it out yourself. Because, you know, then we’d have people, vigilante responses, and all sorts of chaos, people that were too weak to respond would just be left on their own. And so it makes sense that we need some kind of system that deals with, you know, murders and things like that, where we have some, sufficient evidence to think someone has committed a murder, the community’s gonna care about that. And it makes sense, we’d have something like a court where we decide, is the person actually guilty? And if so, what do we do now? What kind of punishment is appropriate, if any, and so that, to me, resonates with the idea of a criminal justice system? I mean, that’s what we’ve called it for decades, we call it the criminal justice system. And it’s for cases like that, that’s the idea, we need to figure out, is the person we think did it actually the person who did it, and if we decide they are, then there can be some kind of government response. And we can call that response justice because it fits with our conception of, there’s been a harm to a discrete person, and the government seeks accountability on that person’s behalf. And that looks like justice and I talked about in the book, you know, there’s surveys of things that we can find kind of widespread social recognition that that’s a justice problem. And then there’s this recent shift in, I’m sure you’ve seen this, where scholars and advocates have stopped using criminal justice system. They’re using the phrase criminal legal system and their critique, punishment system, or criminal punishment. Yeah, even worse, I think of criminal legal system as neutral and criminal punishment as negative. And the critique there is that the system isn’t entitled to this word, justice. There’s so much injustice in the system, that we’re not even going to use the word justice anymore. And so I’ve taken that critique and tried to separate out what I talked about as the criminal justice system, which I just discussed in the context of homicides and our criminal legal system, which is a lot of what is happening in the criminal courts now, which is just enforcing the law. If you said to a prosecutor well, what’s important about this case, the response would be something like, well, they broke the law and they have to pay for that now; it wouldn’t be justice. The paradigmatic case for that are drug offenses, right? When I was a prosecutor and we got a drug case, the people in my office weren’t like, Oh, this is really important. We need to prosecute this person to bring justice to the world or something like that, we would say, well, it’s the person, if the evidence suggested that the person was guilty of selling heroin or something, we would prosecute the case, not because there was some sense of justice-involved, but because they broke the law. And so that’s what I talked about in the book, we were enforcing the law, we kind of felt like we had to enforce the law. In those circumstances, I think that’s what the police would say about what those cases are doing. That’s what judges will say when they’re doing those cases. And so that fits; to me, it is like a criminal legal system, what’s going on there, the courts are being used to enforce the law. And so I talked about in the book that a big part of the mass incarceration story is a shift from using the courts very sparingly to try to just deal with justice issues where we have to have a government response, you have to seek accountability, just because the society demands that, and then we move to a criminal legal system where we got just tons of cases pouring into this system. There are drug cases and gun possession cases, and violation of parole, and all things like that. And what’s going on is we’re enforcing the law, you broke the law. And so you’re gonna have to pay for this. And, over time, and especially because as I said, that crime went down in the 90s, and 2000s, and then stayed down, the cases that came into that vacuum, were these criminal legal system cases, they were drug cases, assault cases, DWI cases, gun possession cases, illegal immigration cases, all these cases that fill that vacuum, and they weren’t . . .you know, people can fight with me about what’s justice and what’s not justice, I’m fine with that because it’s not going to be exactly the same for every person. But on the whole, there were like two different kinds of cases, they weren’t the armed robbery, and the rape and the homicide cases. Now, we were dealing with just tons and tons of drug cases, lots of weapons possession cases, and cases like that. Now, also, at the same time, the criminal justice system that I’m talking about was changing, too. So there’s these two changes going on. One, we’re bringing into the system lots of cases that we hadn’t used the criminal courts for in the past, mostly drug cases, but a lot of other cases as well. Gun possession is a good example. And then the other change that’s going on is for people that are committing the kind of standard core criminal justice offenses, like armed robberies and rapes and homicides, we’ve ratcheted up the sentences tremendously for those too, and those two things are happening simultaneously are how we ended up with mass incarceration. And just to round off this thought, you’ll see a lot of people will be fighting about things. And you talked about like Bill Barr and people that are on the other side. A lot of times the conversations are people talking past each other. So some people are thinking about the criminal legal system, the drug war, and things like that. And then the person they’re fighting with is thinking about homicides, and rapes and things like that. And so they’re, they’re just missing each other in their discussion. And so I think it’s important to keep separate, the courts, the criminal courts that are just enforcing the law, they’re saying, we’re gonna put you in prison, because you carried a gun, and you weren’t allowed to carry a gun, from the parts of the criminal justice to the much smaller part, but I think the more important part, is that we’re going to have a forum for deciding whether this person is actually guilty of murder, that piece of the system is, to me, very different from the piece that says, we’re going to put people in prison for selling heroin and things like that. And we can fight about exactly what should be done in the various cases. But I think it’s important to see them differently. And to recognize that a big part of the mass incarceration problem in America was we expanded our criminal courts to bring in all of these cases that were really just about enforcing the law. They weren’t about justice.

Josh Hoe

Just to take your challenge up a little bit. I think people like Senator Tom Cotton, for instance, knowing a little bit of how he thinks about these things, might say that you could solve the problem of deterrence by making apprehension and sentencing more likely, and at the same time, because there’s a value to retribution, at least in his mind, keeping the severity high, in other words, punishing everyone a lot. But also arrest and sentence everybody. So I guess the question that I have in relation to this notion in the book is – I have a lot of answers to this – but what’s your answer for why mass incarceration is wrong in that world?

Jeffrey Bellin

Let me take on the two pieces. I think there’s two pieces. And yeah, and again, I love this discussion, this is the discussion that America needs to have to move forward, right? The discussion where we’re saying, here’s the other argument, and what do you have to say to the other argument, why isn’t the response to what I’m saying, well, let’s just catch more people? Why aren’t we just catching more people? So let’s talk about that one first. And we’ll talk about that retribution part second because I think they’re both really important. And so for the catch more people part, this is where I think you need to not be an academic to understand this. In the book I talk about just the way the system works in America is not how people think. And the problem is people are watching these TV shows. And in the TV shows, they’re always catching people. And so we used to have, there was a guy in my office, and he used to joke about, the jurors would watch the CSI show. And then they would be like, Oh, I saw on the CSI show, they were getting fingerprints out of the air. And so why aren’t you able to get fingerprints out of the air, like on CSI? And so in reality, right, part of it is, there’s just that technology doesn’t exist, to the extent I’ve confused people about whether that’s a thing, but the reality is, the reason we can’t catch everybody is because we don’t, we can’t prove that everyone’s guilty. It’s not like technicalities or lack of resources, it’s that a lot of crimes happen, and you can’t figure out who did it. And that’s always going to be true, I mean, you could actually change society entirely, we could go to you know, there are some societies like Singapore or somewhere where you have a completely totalitarian system. And so then you can catch everybody, but we’re just never gonna have that in this country where there’s a free country, and there’s a certain amount of freedom that people are gonna have. Also, it’s a giant country of tons of people who have these big cities, crowded cities, and you’re just not going to be able to catch people. And so the story I have in there to illustrate this is these car theft cases we used to always get. And so you know, a very common scenario was the police would see that someone was driving a car that was stolen, and they would pull them over. And so you’d say, Oh, well, that person’s in a lot of trouble. And it’s true, they are in trouble because the police would say you’re driving a stolen car, but the person would say, Oh, I didn’t know it was stolen. And so to win, to prove that case, which is dealt with as a car theft case in DC, we would have to prove not just that the car was stolen, but that the person driving it knew that it was stolen, because the issue was it could have been stolen months ago. And if they didn’t know that it was stolen, if someone had just loaned it to them, or sold it to them – which actually happens, people steal cars, and then sell them to people claiming that they’re not stolen – it wasn’t an offense, so they were not guilty. And so we just had tons of trouble proving those cases proving that the person driving the car knew that it was stolen, because how are you going to prove that, and you know, sometimes you could prove it if they admitted it, or something like that. But most of the time, they didn’t admit it. And it wasn’t obvious that they knew it was stolen. And so we couldn’t go forward in cases like that. And you could say, like, well, I want to stop car theft, I’m going to ratchet up the penalties for car theft offenses. But we were unable to prove these cases. And this is true for a lot of the crimes that most people care about. So robberies, and rapes and homicides, they’re just really hard to prove, not because there’s technicalities, or the judges aren’t severe, or the prosecutors are too easy, or the police are lazy, they’re just hard to prove. Because it’s hard to prove things, it’s very difficult, you could think of anyone as kids or, you know, whatever, you get home and something’s broken in your house. And one kid says it was that kid that did and the other kid says it was the other person who did it, someone says it was the dog that did it, you’re never gonna know, it’s forever going to be a mystery, you know; make that on a much broader scale. And so it’s just not possible to fully enforce these laws in the ways that the legislators kind of make pretend we can. And so we’re always going to have this disconnect between the really severe penalty, and a lot of people that are just not getting punished at all. And that’s just part of the reality. If you go and work in any prosecutor’s office, you’re gonna see that. And this, by the way, ties into what I always say is the biggest problem we have, which is volume, like you can defend the American system in the abstract, but you can’t, it can’t work with the volume that it’s under. And you could just go work in any of these big city offices and work in a public defender’s office, work in a big city police department, you’ll see there’s just too many cases pouring into this system. And so no matter how you set this system up, it’s going to fail in a lot of different ways, including the ways I was just talking about, not being able to prove cases, because it’s just pummeled with all these cases. And so the first thing that makes the system run sanely is not to say, let’s get more people, but let’s shrink, we need to shrink the amount of inputs that are coming into the system if we’re going to have any chance of having a rational system that actually does anything that we want to do. And so that’s the part of the response, well, why don’t we just ratchet up enforcement, it’s just not possible. We’ve seen that over decades, to do much more than we already are. We can’t shift resources around to focus on the things we care about the most. Well, we can’t say we want everything to be severely punished, and we’re just going to enforce everything more. It’s just not possible. And then the retribution point, I talked about this in the book to a degree. To the extent you’re fighting about what should be the right punishment for various actions, I just don’t know how you convince someone. So someone says, if someone sells heroin, they should go to prison for 100 years, and another person says they should have no punishment. Like, you can make arguments about either one of those. And, and, if it’s retribution that you’re fighting about, really you’re just talking about your belief or some kind of amorphous sense of dessert or something like that. And there’s not a way I think to convince people either way, so what you can talk about is, Well, I say it this way, what I think the sentences are doing in the United States right now is that they’re serving as relative markers. And so, and you see this all the time, you’ll see one of the January 6 defendants gets a certain kind of sentence. People compare that sentence to other sentences and say, it’s either too harsh or too light, or too lenient because someone else with a less severe crime got more or less. And so you see a lot of this, like a white collar criminal gets a sentence, and people say, well, a drug dealer would get even more. And so that sentence is too light. And so we should ratchet that up. And, you know, a lot of what’s going on in American sentencing is just comparing sentences one to another. And so what happened over time is when the legislators ratcheted up the sentences, especially for things that aren’t particularly grave and serious, like for drug offenses, like for habitual offenders, and I talked about [this] in the book, the person who stole a jacket in Louisiana and went to prison for life because it was their third offense; if you’re a judge, and you’re sending people to prison for life for stealing a jacket. And then your next case is a murderer, and your next case is a rape. You’re in this weird space where to show your outrage, you have to compete with what you just did for the person with a jacket, or what you just gave for the person who was selling some drugs. And now what I call the punishment auction is going on, you’re always trying to show that you’re being more severe with something. And since everything is kind of ratcheted up, now we’re making everything more severe and everything more severe. And so if you want to say, well, people need to be in prison for some kind of dessert or something like that, I get that, I get that argument, it doesn’t make sense to me, but I know that it makes sense to people. But I still think what we can do is we can ratchet down all the sentences back to how basically they were, and then it would still be we’re treating this very severely because it would just be relative severity. And then the other piece that I think is very important that we lost track of is it used to be that we would say, you get 20 years in prison. And then there was a parole board that would look at, you know, five years in, you know; does it make sense to keep this person in prison any longer based on how things played out, that actually was a really effective way at keeping us from getting prisons full of old and ill people, because at some point, you’re revisiting the question of how long should someone go in and [then] letting people out? And if you’re going to have a system that’s well, we’re gonna put someone in for a really long time at point A, then you need to be reevaluating along the way, does it still make sense? It still makes sense as society changes and as the person changes, and, you know, we’ve stopped doing that, in a lot of jurisdictions where we got rid of parole, and now we’re sending, we’re making, we’re outraged, right in the moment we’re sending you to prison for a really long spell. And we’re never going to revisit that again. That makes no sense to me, even if we’re in Tom Cotton’s world, and we’re thinking that people deserve various punishments.

Josh Hoe

So you go through a lot of different kinds of causes of mass incarceration, one of them that I think I first talked about, probably with James Forman, Jr, several years ago. But this notion that tougher-on-crime policies are actually kind of bipartisan? I think people often assume that Democrats are pro-reform and Republicans are tough on crime. As someone who does legislative work, I know that’s not actually a good map. But can you talk a bit more about this and how it factors in?

Jeffrey Bellin

Yeah, I think this is so important. If you think about any American political change, like a new law passed, or something that we’re going to do differently than we did before. You keep in mind that the change of mass incarceration is a huge change from what we did before, for decades. So from 1970, before, we didn’t have this kind of prison population. And so it was a huge change to go from what we had in 1970, and always before that, to what we’ve got now. And so if you’re a student of American politics, you should say, Well, how could they have done that? How could they have made such a sweeping change, not just federally, but in all the states? And, that’s one of things I talked about in the book, it’s kind of everywhere. And that incarceration is a big problem because it’s a problem everywhere in California and in Texas. It’s in Florida, and it’s in the federal system. And so, like, how do you get this kind of uniform response across the country? Well, the only way that could have happened was that it was both parties, because in America, if one party doesn’t want to do something, it’s very hard for the other party to make that thing happen to make it stick and to make it everywhere, right, if you can think of like, basically, today’s political controversies, you know, Republicans were able to get something in Texas, but they can’t get it in New York, and things like that. And then they can get it federally, but then it goes away and the next election, but what made mass incarceration such a powerful phenomenon over years and years was it was a bipartisan effort. And it’s, you know, it’s not really fair to say it was equally bipartisan. It certainly was true that Republicans got on this bandwagon first, and they were pushing it harder than the Democrats were. And there was this key inflection point where in the beginning Democrats were hesitant to go along with it. But then they kind of gave up and went along. And the paradigm of that is Bill Clinton becoming this “new Democrat”. And you know, making a big point about going back to Arkansas, to execute someone who was on death row there, a controversial execution, and then saying, like, Well, now, no one can call me soft on crime. And that became kind of a blueprint for democratic success. I have in the book that story about Bill Clinton, [who], in his first term as Arkansas Governor had actually pardoned a whole bunch of people, and then was defeated in his second term or defeated at the end of that term, in part because he was labeled as soft on crime. And he kind of learned that lesson and became this model for the tough-on-crime Democrats. And there’s the story about Joe Biden, also the 1994 Crime Bill, where he gets up on the floor of the Senate and says, you know, the Democrats used to say, We want justice, not just toughness, and Joe Biden says, lock the SOBs up. And so this kind of sense that being tough is the new Democratic way to do it. Now, it was a reaction to the Republicans and Richard Nixon, starting this kind of law and order campaign. But as I say, in the book, you know, another person that was pushing this was Ted Kennedy, who was a big liberal hero at the time. And so it was, it was kind of the Democrats getting on board that took away the opposition. So it wasn’t that these ideas weren’t already out there, the Republicans were already pushing it. But when the Democrats kind of join the Republicans, if I can’t beat them I will join them. Now, there’s no one left, once the Republicans and the Democrats are on the same page with something, you know, who’s left to stop that train? And that’s why we see, not just at the federal level, but across state jurisdictions, everyone getting on board with tough on crime, and that’s part of the story of mass incarceration.

Josh Hoe

Here’s a quote from the book: “Despite all of the changes, including expanding police departments and increasing arrests, the one variable that is central to effective policing did not improve: the rate at which police solve the most serious crimes. One possibility: police are too busy with other tasks.” We’ve already talked about this a little bit, but I think it’s important because there is a weird kind of incentive structure here. You know, we think that everyone is set up to prosecute crimes or to protect people or to get public safety. And the truth is, that they’re incentivized to get people incarcerated in a sense, regardless of if that is the best outcome. Or if there aren’t better ways to use their resources, there are clearly opportunity costs left and right to the way that they do things. Can you talk a little bit more about this kind of agenda-setting problem? In a sense, it may even be a moral hazard problem that we face with policing in the United States.

Jeffrey Bellin

Yeah, great. And this was another insight, that it was important for me to have gone through this in the trenches to understand just what you’re talking about. And that was that there’s a difference in the ability of the police to catch people and the prosecutor to prosecute some cases versus others. And it kind of lines up with the cases we care about the most are actually the hardest to catch people; the most difficult to get people to report, hardest to catch people and then hardest to prosecute. And when those cases – and I talked about these, like civilian generated cases – or like rapes and homicides and things like that, and then there’s this other group of cases, and we talked about this, the criminal legal system cases that are like drug cases, and gun possession cases. And also assault cases. If you think about a typical assault case, someone calls 911 because they’re being attacked, or someone’s in a bar, the bartender calls 911, there’s a fight or something, the police come to the scene, it’s actually a really easy case for the police to solve, right? Because they come to the scene, and the person in a domestic violence case, for example, they just say, well, John hit me, right. And that person, often John is right there. So the police can arrest that person right there; the case is solved and closed in one minute. And that’s the same with bar fights, the person is typically on the scene, and then even easier, like drug sale cases, a lot of the drug sale cases I saw, the DC police had a unit and they would send an undercover officer onto the streets. The officer would buy drugs from someone, the team would swoop in and arrest the person that the officer just bought drugs from. The officers would present that case to the prosecutors, it was a cut-and-dry case even in DC, and it was very easy to prove that case. And then gun possession. Gun possession is the same. The case is like a police officer testifies you know, I stopped this person. I looked in their pockets. There was a gun. I stopped this person. I looked in their backpack. There were drugs. The criminal immigration cases, same thing. It’s like this person is in the country and they’ve previously been deported. easiest case in the world for a prosecutor to prove. And so part of what happened is we had all these, after this crime surge in the 70s, we had all these resources, to send in more police, more prosecutors, and then the crime goes back down. And we could have avoided mass incarceration because we could have just gone back to how we were. But instead, crime goes back down. And all these police and prosecutors and courts now just turn their energy on what’s right in front of their face. And so that’s the 911 calls that are coming in for assaults. That’s the drug cases, they can just generate as many of them as they want, in a big city gun possession cases that are like, you know, easy to prove once you catch the person, easy to prove. And so the prosecution and police are just in court. So it’s easy to punish because it’s easy to get convictions in these cases. And also, because it’s so easy to get convictions, these cases are, I say, like tailor-made for plea bargains, because you kind of see what’s gonna go, you know, the police are gonna show up for trial, you know, there’s not gonna be any twists and turns. Now, maybe the police are lying, but they’re, they’re good at testifying. They’re convincing the juries, these cases typically end up with convictions. And so we’ve got all these new resources, police, prosecutors, and they’re, they’re aimed at whatever’s in front of them. And now it becomes these easy criminal legal system cases. And I show this in the data, conviction rates go up, because now we’re focused on cases that it’s easy for prosecutors to, easier for police to catch people, and, you know, bring the case of the prosecutor, easy for the prosecutor to win. And this is a sharp contrast to cases like rape cases and robberies where the police arrive at the scene after this crime has happened. But it’s very hard to figure out who did it. And even if you get a suspect, it’s kind of hard to prove that they were guilty. And those are difficult cases to prove. And so this shift to, you know, like you said, moral hazard. I think one of the ways, I always say this to people, if you want to understand big city criminal justice systems, think of your local Department of Motor Vehicles, like it’s not like what you see on TV, it’s more like just any other bureaucratic agency. It’s a government agency. And they’ve got these kinds of vague marching orders. And it’s like, well, the police are gonna, if you’re a prosecutor, police are going to bring cases to you. And then your job is to process those cases in some manner. And that’s what they did. They just prosecuted the cases, and any bureaucracy kind of gravitates towards what’s easy to do. And these cases were easier. And that’s what we see in the data, just many more of these drug cases, assault cases, gun possession cases, illegal immigration cases, and that becomes a large chunk. Now all these pieces are part of the puzzle. It’s not like that’s just the problem. It’s not like violence, crime, all these things are part of the puzzle. And one of the things I’ll just mention, part of what’s unique about my book is I’m willing to embrace that it’s all these different things, right? I think a lot of people, to sell their book, are here’s the one thing that’s causing it. That’s not me, I wrote a book that’s here’s all the things. One of the other pieces we haven’t touched on too much is parole revocations, [which] become a huge part of this story as well. And probation, people getting violated on probation. That’s actually like a third of prison admission. So a huge chunk and no one ever talks about all these things are part of the story. And it makes it so if you’re talking to an agent, like, say, I was at the beginning of this process, and you’re like, here’s my take on mass incarceration, it’s much more complicated than people think, there’s tons of things contributing. The agent is like, well, that’s not going to sell, right? But maybe it’s not going to sell, but it’s actually the right explanation, and is what you need to know if you want to change the system, is each of the things that are contributing, and all these parts I think a lot of people are fighting about, well, it’s not drugs, and it’s not race. And it’s not the federal system, but they’re all kind of right in a way. Yeah, it’s not any one of those things. But then they’re like, but it’s this instead. And that’s wrong, it’s actually all of those things, is the explanation. That’s why it’s such a big deal and such a challenge to tackle.

Josh Hoe

So as we start to turn towards your solutions, and you’re right, there are lots of details throughout the book. And I figure it’s better to kind of get at major themes and let people read the book and get the details. But before we turn to your solutions, which I think are actually fairly unique, and you take some big swings, and I think they’re good swings. You know, I was talking to someone the other day, who was talking to me about how it is becoming normal in their state, for a few of the crime beat reporters to go after judges publicly, whenever they reach a lenient decision, or what they perceive to be a lenient decision. In so many of the areas you highlight, politicians, police, prosecutors, judges, these are all really in a sense, political questions, their responses to political pressure, led by people in the press. How do we get – before we talk about your solutions – the old saying that politics is the art of the possible, you know, how are we going to get to big swings and radical solutions, in a world in which most people, and I think this is borne out in lots of research and lots of Public Policy Research, still believe the story that you say is kind of ridiculous at the beginning, that we’re doing this to solve crime. I think you know what I’m saying.

Jeffrey Bellin

Yeah, I do. Again, this is the question. And so I was kind of half joking, but it’s true, that there’s two, there’s … so one thing about my book that makes it difficult to sell is, it’s not here’s the one thing that you never thought of that causes mass incarceration, it’s like, here’s all the things that are causing this tremendous problem. The other thing about it that makes it less palatable, I think, to some folks is, because part of it is, is what you’re saying, you know, my diagnosis of the problem is it kind of says that we’re all to blame to a degree. I’m not one of the people that says, Oh, the American public is fooled, and they don’t realize what’s going on, if they really knew they would be outraged. You know, I think the American public is part of this dynamic. And it’s not just that politicians are fooling them into thinking that we should lock people up and stuff like that. I think politicians are saying that in part because voters react to that, voters kind of like this message. And so that’s the challenge, what you said is exactly the challenge. If one of the ways to, you know, we could say here’s the right way to change it. But to get these changes enacted into legislation, or get them to translate into elections, and for judges, and prosecutors and mayors and things like that, we need to get the voters to understand some of the stuff that we’re talking about. And how do we do that? And so, yeah, this is a crucial thing, one, to see that we need to get people to understand this message, and then two, how do we convince them? And that’s where I think, you know, some of the arguments that people are making are self-defeating, in a way, and so you know, saying it’s just race, or it’s just prosecutors, or it’s just drugs, right? Like these things, they’re not going to work in the long term, right? We’ll get a few people, it gets a group of people that really care about that one thing, on board. But what we need is a coalition, we need a whole, we need everyone, well, I guess you need like, 50% or something, you know, depending on how gerrymandered the jurisdiction is, to feel, the way that we’re talking about these issues, and how do you do that. And I think that we have to just talk about these issues, we have to get people to engage with the thing that you started with which I think, my instinct is that you know about this problem because you’re dealing with policymakers. And so, you know, to get through this idea that we’re not saying that it’s not bad for people to deal heroin, or it’s not bad for people that commit assault like these are bad things. The point is the solution to these problems, how do we deal with these problems? It’s not incarceration, and it’s not incarceration for longer, and kind of disconnecting this idea between this is the problem, and then incarceration is the solution. Right that like, I think, attacking that, I think that’s the weak spot in, you know, the policies that got us mass incarceration. And that’s why, you know, I try to frame in the book this argument about, I’m not saying crime isn’t bad. I’m not saying there is no crime, which sometimes people start arguing that, and people know if there’s crime or not. The way to deal with this is to say, there are better, more effective ways to deal with the real problem of crime. And, you know, the most obvious example is the drug war. It’s just clear as day at this point, that we can’t stop the flow of drugs by putting people in prison. Like it couldn’t be clearer. But what I argue in the book is that it also applies to other things that people are uncomfortable talking about. But it actually applies to a lot of other things that we’re treating in the criminal courts that we didn’t used to. And I think getting that message now it’s hard, right? but that’s the message. And that’s what I’m doing, that’s the point of this book. That’s why I didn’t want to write a book that was more catchy, because I think it doesn’t get you where you need to go, which is to get people to understand, you know, the way that all these little pieces are working, is fed by, like you said at the beginning, this one idea. And the one idea is tougher stuff stops crime. And if we can dismantle that one idea, then I think we’ll be able to get people on board more generally. But that’s the idea, you’re right, that stands in the way of a lot of the reforms, especially the most meaningful ones.

Josh Hoe

So your big swing, well, there’s a couple of them. But the first big swing is that you think we should essentially just go back to the way we did things in the 70s. Do you want to talk a little bit more about what that looks like to clarify?

Jeffrey Bellin

Yes, so when I first started talking about this, you know, like a lot of bad stuff went on in the 70s, and this is before I was even born.

Josh Hoe

I lived in New York City in the 70s. I was only three. But that was not the greatest period of New York City.

Jeffrey Bellin

And you know, you know, outside of criminal stuff. There’s lots of terrible things that we were doing in the 70s that we’re not doing anymore. And I’m not I’m not suggesting we go back to that. So I try to be careful in the book when I say, with respect to the use of incarceration, that’s the thing I want to go back to. We didn’t use incarceration the way we’re using it now.

Josh Hoe

I definitely wasn’t saying that everyone should go back to bell bottoms was your argument.

Jeffrey Bellin

I actually, it’s funny, you say that. in one of the versions of the book, I had a graphic that was the top shows like Laverne and Shirley or something. Like, I’m not saying we need to go back to watching Laverne and Shirley. But just this one point, it’s just kind of interesting, because it’s one of the things I used to try to say, we can do this, we can go back, we can have these low incarceration rates, we had them for a long time. It’s not as scary as people think. And if you say to people, well, let’s abolish the system. That scares a lot of people, they’re worried about what the replacement is. Whereas if you say, well, let’s go back to what we were doing with respect to incarceration in the 1970s, that might still scare some people, but it’s not as dramatic because we lived with that, for a long time, we had a functioning society, we were punishing the serious crimes even in the 1970s. And so that’s what I’m talking about, we can go back to 1970s level incarceration rates, that’s a doable goal. And we know that because we’ve done it before, and each state would end up, you know, where they were in the 1970s. That would be fine. I’m not saying every state has to do exactly the same thing. I just think you couldn’t, right, for the reasons you talked about. There’s different politics in every state. But in terms of setting a benchmark that’s realistic that people can grab onto, you can say, we can return to the incarceration rates that were the norm for this country for decades. And, you know, the data, as you go back, it gets a little strained. But certainly from 1930 to 1970, we had an incarceration rate of like about 100 per 100,000. And then, you know, it went up to 700 per 100,000. recently, but there’s no reason we can’t go back to those incarceration rates, which are also the incarceration rates that we see with the kind of countries that we typically compare ourselves to. And so that’s the benchmark that I give, and I think it’s just useful. You know, it doesn’t have to be exactly that, but I think it’s useful to have something to say to people because they’re going to do this now. And they’re gonna say, Well, look, we’re no longer the number one incarceration rate country, have we solved mass incarceration? Are we done now? And I think, you know, we have to, we have to have something to say, besides just let people out, I think there’s a valuable benchmark in saying, let’s go back to the historical norms for this country because we lived with that. And that was a system we could live with.

Josh Hoe

You have a lot of solutions. Just to tease another one. You talked about getting rid of the federal prison system, which I think a lot of people I know would agree with that.

Jeffrey Bellin

I’m gonna have to clarify again on that. But yes, okay. Almost all, I say almost abolish, something like that. But yes, there would be a bit and this fits my point, right, that if you look at what I talked about as the criminal legal system, the federal system, you look at the data, it’s almost entirely drugs, gun possession, and criminal immigration cases, and then supervision for those crimes. That’s almost all of it. Now, there’s still some left. And that should stay, like things that only the federal government can do, like prosecuting police officers and things like that, that are really difficult problems. We can have the DOJ do that or like, you know, president corruption cases, right, like that kind of thing. I don’t want to freak out Attorney General Garland. So just to be clear, we can have some of the federal systems still, but we can get rid of this criminal legal system, which is almost all of what it is. And it’s the same point in the 1970s. It was just this small thing that did things only the federal system could do. And then like I say, the explanation for the growth of the federal system is that fighting crime became popular, and the federal politicians didn’t want to be left out. So that is one of my more radical solutions, but it’s abolish most of the federal system, not the entirety.

Josh Hoe

I mean, one point you’re making over and over again, is that nuance is important, and I certainly appreciate that. I may be overselling a few of the things.

Jeffrey Bellin

You’re like, you’re just like the agents. One of the agents told me, he was like, what you should do is turn that chapter that you just mentioned, that should be your book. So they wanted me to just write the whole book about that because that was the exciting part.

Josh Hoe

So I do want to talk a little bit about one thing, which is that you talk about, there’s a section at the end where you talk about increasing the number of police as a solution to crime, based on a lot of research. I’ve read a lot of that research. From my perspective, when I read that research, what I found is that what they mean is that if police are in a particular place at a particular time, they deter crime in that particular place at that particular time. And I get that hotspot policing can be effective. I’ve had Thomas Abt on the podcast. But there’s a lot, most crime doesn’t happen in a particular place at a particular time. So I find that they always make this correlation to kind of how that would reduce homicides, and it might in those particular places where a lot of those things happen. But it’s not really just as simple as just adding more police. Right?

Jeffrey Bellin

You’re right. And one of the things I tried to do in the book because I’m trying to reach a broad audience, is I try not to say things that are just like, take my word for it, like, I don’t want more police, I do want more police. And so you know, when I talk about things that we can change, or things that I think caused mass incarceration, the book is just full of data, like, here’s why I think it’s drug cases here’s why I think it’s assault, here’s why I think it’s gun cases and just all the data I can find to fill in that explanation. So you’re not just relying on what I’m telling you, or what I think should happen. But you’ve got the data. And so you’re right, there’s these studies that suggest that more police leads to less crime. And what I’m trying to think of in the latter half of the book or the latter portion of the book is how can we decrease crime in other ways than trying to ratchet up penalties? And so one of them is that more people [are] preventing crime? And so you’re absolutely right, that there’s a lot of nuance to this. And because part of the story I just told was, we had all these police, and they just started focusing on things besides the things we care about. And so you know, it’s very dangerous to have a lot of law enforcement agents, because they might start doing things you were not expecting or wanting them to do. And so one way to think about, you know, what these studies are showing, and I think this makes sense, is, it doesn’t really have to be police, what you need is people focused on the problem. And it can be violence preventers, or it could be social service people or it could be any type of person trying to solve the problem of homicides in the city block, or trying to solve, you know, the problem of rape in a certain area, like wherever these problems are, we need to bring resources, and resources typically mean people, to try to solve these problems. And one of the things I think is just very interesting about American policing, that people don’t talk about, [we are] very quick to say, the police shouldn’t have drones, or the police shouldn’t have facial recognition technology. What I think of is, what about guns? Obviously, there need to be some guns available to police. But if I’m saying we don’t need to react to the problem necessarily with police, you certainly don’t need to react to the problem, these problems, with police walking around with guns all the time. That’s not the answer to a lot of these problems. And so we can certainly, you know, compromise on, well, if you don’t want to add police, I understand why people might not want to add police in certain areas, what I want to do is just prevent crime. And so there are these studies that show you can prevent crime by lighting, and you know, police and videos and things like that, and technology. And so like, let’s take advantage of that. And if we don’t want to use police, we’ll use someone, we will call them just like security or something, we won’t give them guns and we won’t have them refer cases to prosecutors, or whatever. But this is just, in the earlier discussion we had, we need like, if we want to change the system, I think it’s naive to think you’re going to be able to just reduce the severity without also doing something about the crime that kind of generates the severity. Otherwise, we’ll just keep being in the same pattern where we’ll get some reform, and then crime will become a problem because it’s always kind of ebbing and flowing. And then we’ll get more severity again. And so I think we need to think of it as two problems that we’re solving, we’re solving too much incarceration, and we’re solving too much crime, and one doesn’t solve the other. But they’re both kind of related and we need to pay attention to both.

Josh Hoe

I always like to ask people if there are any criminal justice-related books, I think we talked about this earlier that they like and might recommend to our listeners. Do you have any favorite books currently?

Jeffrey Bellin

The other book I mentioned is Ghettoside by Jill Leovy. I don’t know if you’ve seen that one. I think that’s just a tremendous book about the problem we were just discussing. That’s the book! I just say for the listeners, you didn’t know I was going to mention that one. And he added it on the screen, as soon as I said it, but a really interesting take on, you know, we can solve these problems if we devote more resources, so just kind of the thing we’re talking about, and then one like so those are pretty famous, one that people might not be aware of. There’s one called The Feminist War on Crime by Aya Gruber. And that one again is like cheating by talking about books that are similar in perspective to my book, but you know, talks about, you know, a lot of what I said about how we’ve ratcheted up severity, doesn’t necessarily mean we did it for bad reasons. Like often the ratcheting up of severity was noble, or at least had noble intention. So like taking domestic violence more seriously, I understand where people were coming from. But her book does a nice job of explaining just with that little piece of it. Why, that effort, you could criticize it and that kind of ties into some of what I was talking about with assaults, like one of the big changes over time was how we treated assaults. And that’s something that her book offers a lot of perspective on. So that’s three. Is that good enough? I did three.

Josh Hoe

Oh, that’s great.

I always ask the same last question. What did I mess up? What question should I have asked, but did not?

Jeffrey Bellin

You know, that’s so funny. So I told you I was a prosecutor, there was another prosecutor in my office named Steve Yarosh, maybe he’s listening. He used to ask that at the end of his cross-examinations, not did I mess up? But he said, was there anything I didn’t ask that I should have asked? And you think, I never heard that. And people would just be floored that he would ask that because you’ve always said like a lawyer never asks a question they don’t know the answer to. And he was just like, so open about what he was doing. And he would ask the question, and there isn’t really an objection to it. It’s so funny that that reminded me that he used to ask that so I think it’s a great question. I’ll say this. One of the things I touched on that people may not appreciate, the book doesn’t have a “this is the one thing”, and it’s an Academic Press book. And so that means, the question might be, why haven’t I heard of this book? Right? And so the answer is because it’s an Academic Press book that allowed me to write the story that I told, but I purposely wrote it for everyone, for an audience beyond the academic world. And I asked them to price it so that people could buy it. So the paperback is reasonably priced. And so people should just appreciate that there’s no marketing for the book. It’s just me going on a podcast. And then people like Josh, and I should say this, you know, he does a great job of finding people. So you could take me out of the equation, but the people on his podcast are like the Who’s Who of who you want to hear from. And so, so that’s why you haven’t heard of this book. And you know, if you like it, or if you get it and read it, or just like the podcast, what I need is word of mouth. So hopefully people will tell others about the book and we can get the true story of mass incarceration out there.

Josh Hoe

And where can people find your book?

Jeffrey Bellin

So you can find it on Amazon. That’s the easiest place to buy it. But make sure you get the paperback because the hard copy is priced too high. Don’t tell the publisher I said that.

Josh Hoe

Well, thank you so much for doing this Jeff, it was really great to talk with you.

Jeffrey Bellin

It was a wonderful conversation. Thank you.

Josh Hoe

And now my take. In some ways, this is one of the most important interviews I’ve ever done. We are already starting to hear from candidates and pundits about the need for much tougher anti-crime measures. We’re hearing 2024 GOP candidates call for executions, firing squads, and executions of drug dealers. And recently in New Jersey, I read an article that talked about Democrats tripping over each other to call for enhanced penalties and mandatory minimums. They are all wrong. What they are doing is immoral and uninformed. Crime has not increased because of a lack of toughness. In fact, in most of the places it increased the most they had the toughest laws, the meanest prosecutors, the most funded police forces and the most tough-on-crime leadership. People, we have to stop falling for all of this nonsense. We have to refuse to play these games because the end result is people’s lives. Mass incarceration is not a solution to crime. Tough-on-crime laws are not a solution to crime. And the best solution is almost always more thoughtful and smart interventions. Not even more counterproductive toughness. We have to respond to these calls for toughness every time we have the opportunity, and we have to use our own platforms to educate people about the facts.

As always, you can find the show notes or leave us a comment at decarcerationnation.com. If you want to support the podcast directly, you can do so from patreon.com/decarceration nation. For those of you who prefer to make a one-time donation, you can now go to our website and make a one-time donation. Thanks to all of you who have joined us from Patreon or have given a donation. You can also support us in non-monetary ways by leaving a five-star review from iTunes or add us on Stitcher, Spotify or from your favorite podcast app. Make sure and add us on social media and share our posts across your networks. Thanks so much for listening to the DecarcerationNation podcast. See you next time.

Decarceration Nation is a podcast about radically re-imagining America’s criminal justice system. If you enjoy the podcast we hope you will subscribe and leave a rating or review on iTunes. We will try to answer all honest questions or comments that are left on this site. We hope fans will help support Decarceration Nation by supporting us on Patreon.