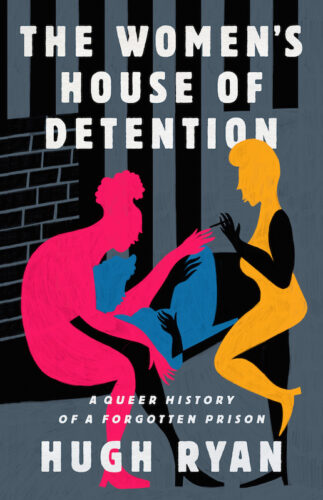

Joshua B. Hoe interviews author Hugh Ryan about his book, “The Women’s House of Detention: A Queer History of a Forgotten Prison”

Full Episode

My Guest – Hugh Ryan

Hugh Ryan is a writer and curator. His first book, When Brooklyn Was Queer, won a 2020 New York City Book Award, was a New York Times Editors Choice, and was a finalist for the Randy Shilts and Lambda Literary Awards. He was honored with the 2020 Alan Berube Prize from the American Historical Association. And he is my guest today to talk about his new book The Women’s House of Detention: A Queer History of a Forgotten Prison.

Watch the Interview on YouTube

You can watch Episode 132 of the Decarceration Nation Podcast on our YouTube Channel.

Notes From Episode 132 – Hugh Ryan – The Women’s House of Detention

The books that Hugh recommended were:

“The Streets Belong To Us” by Anne Gray Fischer

“We Do This ’til We Free Us” by Mariame Kaba

Full Transcript

Apologies in advance, Ann Espo usually does an incredible job editing these transcripts, but she is on vacation so the editing for this episode will not be very well-done.

Joshua B. Hoe

Hello and welcome to episode 132 of the Decarceration Nation podcast, a podcast about radically reimagining America’s criminal justice system. I’m Josh Hoe, among other things, I’m formerly incarcerated, a policy analyst, criminal justice reform advocate, and the author of the book, “Writing Your Own Best Story: Addiction and Living Hope.”

Today’s episode is my interview with Hugh Ryan about his book, “The Women’s House of Detention: A Queer History of a Forgotten Prison. Hugh Ryan is a writer and curator, his first book, “When Brooklyn was queer,” won a 2020 New York City Book Award, was a New York Times Editor’s Choice, and he was a finalist for the Randy Schiltz and Lambda Literary Awards. He was honored with the 2020 Allen Berube prize from the American Historical Association. And he is my guest today to talk about his new book, “The Women’s House of Detention: A Queer History of a Forgotten Prison.

Welcome to the Decarceration Nation podcast Hugh

Hugh Ryan

Thanks, Josh. I’m excited to be here.

Joshua B. Hoe

I always ask the same first question, which is how you got from wherever you started in life, to where you are writing a book about the house of D. in New York City,

Hugh Ryan

Slowly and accidentally is the most honest answer. I always loved writing. It’s been a passion of mine my whole life. And I’ve always loved history, too. But neither was anything that I ever studied. I was a Women’s Studies major in college. And then afterward, my first job was working with Well, I stayed on at my college for a little while. But then I moved to New York City very quickly and ended up working as a youth worker at an organization that mostly served homeless LGBTQ youth. So I always kept this interest in New York City in history, in urban studies, in all of the things that affected the youth I was working with as part of my life. But it wasn’t until I had done that for a number of years and realized that as much as I loved social work, I had burned out and that it wasn’t where I wanted to devote my time and energy. Writing just demanded I spend more time on it, you know, I kept putting it off and saying, oh, that’s something I’ll do when I retire. That’s something I’ll do in my spare time. And then I was about 30. And I just was like, I want to do this. This is what I want to do. I have to at least try, you know like it’s okay to fail. But let me at least try to fail for and so I started off thinking that I would write about funny personal essays, Allah David Sedaris, you know, I thought I was going to be really cute and gay and funny. And I went to my grad program, which was really wonderful the Bennington writing seminars, a low residency MFA program. And I realized that in particular, like writing about myself, I wanted to write nonfiction because I had absolutely no imagination. And I couldn’t do fiction if I tried. And I did try, but I just was not good at it. So I had to find another thing to write about. And as you mentioned in the intro, I’m also a curator and I do a lot of historically based queer curatorial work through an organization I founded called the pop-up Museum of queer history that used a lot of the empty space from the 2008 recession, to do these locally sourced queer history exhibitions. In about 2013, we decided to do an exhibit in Brooklyn on Brooklyn’s queer history. And when we worked in the local community to find people to make the exhibits for it, something very strange happened, that didn’t happen in any of the other communities we went to, people didn’t have a lot to say, we found that people just didn’t know very much about the queer history of Brooklyn. So I started doing the research myself, and I got a grant from the New York Public Library. And they said to me, when you’re done doing this research, you should have your book proposal together. And I was like, Oh, my gosh, this is it. This is where everything comes together my interest in the city and marginalized populations in history and power in writing, it’s going to be this book. And so that’s how I started to write my first book when Brooklyn was queer. When that book finished, I had all of these kinds of dangling threads that I was interested in. I wrote a little bit in that book about prisons as collectors of information about queer people, but I wasn’t quite yet thinking about prisons as major aspects of queer culture and queer history. So I knew that a couple of my protagonists from that book had passed through the women’s house of detention, which put it on my radar. I had heard from a number of folks in the city Jay Toole, really important queer activist, with Queers for Economic Justice, gave me a tour of the West Village and told me about her time in the women’s house of detention. And then I came across this statistic from the Williams Institute at UCLA, which said that 40% of people currently incarcerated in women’s prisons and detention centers for girls identified as LGBTQ. And I was just shocked by that number a 40%. That’s a that’s a crisis. How is this not a top-of-the-line issue for like, every queer organization out there? How did I not know this? Right? Oftentimes, that’s where I find I’m most interested in the work How did I not know this? How could my ignorance have kept me blind? And what do I need to undo that ignorance? And that’s how I really came to start writing this book. I saw that my people from my first book brought me to the house of D. I heard from Jay Toole about the importance of it and how she forgot She felt that her life was being forgotten in her experiences. And those are the people like her. And then I saw that statistic which told me that this history is really still active in the present day. And I need to understand what it is.

Joshua B. Hoe

I know that ignorance goes in very far, because I grew up as a kid in New York City. And I’m pretty sure I didn’t even know that the House of detention existed. This book had to be incredibly difficult to research. You’re telling the stories of a bunch of people, in addition to sharing the history of a prison that not only no longer exists, but I don’t think if it’s like most prisons kept particularly great records. How in the world did you manage all of this? And what was your process?

Hugh Ryan

It was a long one, the first year of working on this book, not exactly full time, but close to full time, I also have another job. And I do a lot of other things. But where I was really focused on this, I just spent it trying to figure out where I could find these records because as he said, prisons produce tons of records, but they’re shitty, right? Not only are they often wrong, but the kind of information that they capture is very limited. And it’s through a lens of carcerality right? So

Joshua B. Hoe

a lot of times, they intentionally don’t, a lot of times they don’t, they intentionally don’t capture a lot of the information that would be the most useful.

Hugh Ryan

Yeah, and certainly, regardless of what they do capture, they don’t look at the fullness of a person’s life, right? They’re not interested in those details, at least not in the record keeping. So I knew that couldn’t tell this story from existing prison records. Also, there just aren’t that many of them for the house of D. So that was an added level of complication. But even if they existed, they wouldn’t be good enough. I started off looking at the files of major LGBTQ organizations, the matching society, The Daughters of Biletis, kind of the first ones that come out in the 1950s. And then find a lot there. There were some things about other kinds of carcerality and criminality but mostly it was in concerned with gay men arrested for soliciting or drag queens and kings arrested for cross-dressing, specifically gay crimes, but not kind of the issue of incarceration, generally. Then I looked at LGBTQ periodicals, again, didn’t find very much until the very end of the period I was interested in because the house of D stood from it started being constructed in 1929. And it was finished being torn down in 1974. In the end of that period, in the late 60s and early 70s, I started to find some of the kind of like liberationist publications, the activist publications, late 60s, and early 70s. And they talked about it a little bit, mostly in women’s publications, but nothing about the earliest years. Then I looked at the files of famous LGBTQ New Yorkers and or other people who pass through New York in the hopes that they would mention the house of D, again, little things, but I wasn’t getting it the lives of the people who had been incarcerated. I certainly wasn’t getting things from their perspective. So I stepped back for a moment and asked myself, How do we end up in the public records, right, there are two ways either you have power. And so you get interviewed, you publish a book, you have belongings and a home that get passed down to your ancestors who then pass those on into the world, or someone has power over you. And you enter the public record as the raw material for their entry into public history. So jails are one way that do that with people without power. But what I hit on, thanks. My own experience was social workers. When I worked as a social worker, we kept copious files that were interested in the full lives of the people we were working with. And I knew that in the earliest years of the prison in the 30s, and 40s, they very distinctly believed and understood that queerness and carcerality were deeply connected, that being queer, particularly in the case of people assigned female at birth, being not properly feminine, would lead you to be incarcerated. And being incarcerated would lead you to have queer desires and experiences. So I was betting, with social workers working with formerly incarcerated people would have the kinds of notes I needed to tell these stories from the point of view of these women and trans men, and non-binary folks. In Part, I was inspired by the work of Saudi Hartman, who was a historian who talks about using the imagination, and she’s talking about using it to fill out parts of lives that we can’t find to tabulate these ideas of what might have been. And I didn’t do that. But I did use it to think about the perspective of the people I wanted to write about and where their stories might be captured in history. by imagining myself into the lives of the subjects, I could start to think about where I might find them in the archives. And that’s really what worked for me, there was a collection by the women’s prison Association, that was in the New York Public Library that had been there since the 1980s. And no one had ever really looked at it. And it was 140 boxes…files. And as soon as I opened it up within two hours of my first day looking at the records, I found one of the major files that would become one of the narrators who walked me through the first part of the book, a woman named Charlotte B. And I knew from that moment that this was the archive, it’d be mostly drawn from a lot of other archives that are present in the book, but for getting the fullness of the lives of people who are incarcerated in the house of D in the earliest years. It was really the women’s prison association that made me made it possible.

Joshua B. Hoe

So in a world where prisons and in jails are usually located, hidden away, located far away from non-incarcerated, generally white folks, how did the house of detention come to exist right in the middle of the village?

Hugh Ryan

Well, a couple of ways. The first thing that really surprised me is that there have been prisons and detention centers in Greenwich Village, since the 1790s. Since Greenwich Village wasn’t even part of New York, it was literally a village up the river. In fact, the saying, “send someone up the river,” comes from when they would put incarcerated folks on boats in New York City, and send them to Greenwich Village to prison. Right. Is that true? Yeah, it’s often, it’s often said that it sinks in, but it precedes SingSing. It’s about Greenwich Village, and about new gate prison, and specifics. And so there’s always been there has never been a Greenwich village that has really truly existed, as we know it today as part of New York, that has not been involved with detention centers, right? So that’s one of the things I really tried to drive home is that you cannot understand Greenwich Village without understanding the history of prisons, the first farmers who were there when that first prison opened up. In fact, we’re excited by it, because they felt that this was going to bring industry and buildings to their neighborhood and connect them to the city, right, they didn’t see it as a net negative. And in fact, that idea that having a prison in your neighborhood is a net negative only really comes about in my research in the 1920s and 30s. This is really pioneering and amazing sociologist named Caroline ware, who spent all of 1920s, the entire decade studying Greenwich Village, she was in Columbia University. And she published a book about it. And she says that was there two groups that kind of live in Greenwich Village at that moment, there are the kind of local people most of whom are Italian and Irish immigrants, or other European immigrants, along with some remaining black Americans who had lived in that neighborhood earlier when it was a black neighborhood, which had largely by that point been destroyed. But there were still some pockets of that community. For these folks, in general, having the prison there wasn’t seen as a negative because they didn’t see being arrested and incarcerated. It’s something that happened to others, everyone broke the law in their view, some people were punished for it. And it was nice if it was your family and your friends or your loved ones to have them nearby, right? You could see them, you could talk to them. You could hear them, you could yell things back and forth. visiting them didn’t take two hours and $10 to get there and back. The other group of people that who come into the village at this moment, who are more of a striving and professional class, the people we today will call gentrifiers who are moving there because the architecture is beautiful. Because Greenwich Village is now centrally located and expanding New York City, what had once been far away in the 1700s is now the center of the city, right? So you want to live there. These are the people who start to say, Oh, the prison shouldn’t be here. It doesn’t belong here. It’s a blight on the neighborhood that has been inflicted upon us, right? Because they don’t know the history. And they don’t care about the history. They claim the neighborhood. In fact, when they get rid of the house of D what those landowners will say, the Greenwich Village real estate associations, they say, “Oh, this was a center of the city until the prison opened, and the prison destroyed that area,” which is completely false. It’s an inversion of the actual history, right? But it was seen for them as a real net negative and something that needs to be gotten rid of. It’s very much that kind of NIMBY, not in my backyard attitude.

Joshua B. Hoe

And it was originally designed to be kind of a different kind of prison, or even I guess, Art Deco, which I’ve never heard of a prison being Art Deco before. But before it even opened most of those plans were kind of thrown out the window, so to speak. Is that correct?

Hugh Ryan

Yeah, it opens towards the end of what’s known as the reformatory movement and women’s detention, which is this late 90s, late 19th century, early 20th-century movement to have these big, usually rural campuses, where younger women who were incarcerated for less serious crimes, generally women who were white, though not always were put because they thought they could be reformed, hence the name reformatories. However, these campuses were very expensive, they often did not work the way that the people incarcerated women in them thought they would work. And by the 1920s, they were really going out of style. They were seen as expensive. The Progressive Era was starting to end. And so these kind of like, really socially conscious interventions, whether or not they worked or not, they were intended to provide more money, resources, and support to formerly incarcerated and incarcerated people. And those were seen as a waste of money. So by the time we get to the house of D being built 1929 We’re on the verge of the Great Depression. All of these plans have been built in the 1920s. While there’s this idea of the reformatory movement, so we’re gonna have this big jail, not a prison, right? It’s going to be a jail because the women’s court is also in Greenwich Village. It’s gonna be right next to the court so women can easily go to their trials and easily get through their sentencing etc, etc, people can easily see them. And we’re going to five stories of hospital in it largely to deal with women and girls who were being incarcerated because of something known as the American plan, which saw any woman, any poor woman who had syphilis or gonorrhea as a criminal liability and a danger to men. And so women could be incarcerated without ever being charged or found guilty of something, simply if they had gonorrhea or syphilis, or were suspected to. So the hospital was going to take care of those cases, along with drug addiction. By the time they’re breaking ground on the start of the prison in 1929, the stock market has crashed. And suddenly those plans are no longer of interest to anyone. When you get rid of the hospital, it becomes a single floor. And Florida really goes unused for most of the prison time. And instead of a jail, it becomes a jail and a prison combined. This is often referred to as the original sin of the house of detention, because those are populations with two very different needs. And the building is built for a jail population that will only be there for a short period of time, that does not necessarily in their eyes need a lot of recreation space, a lot of vocational space, a lot of educational space, a lot of hospital space. And instead, we get people there for years at a time in a building that was built for way fewer people than it actually ended up housing with no room for services.

Joshua B. Hoe

One of the things that surprised me the most as I was reading and kind of immediately stood out was when you said many of our old and you already alluded to this a little bit above, many of our oldest and most extensive records of queer history come from our carceral system. That seems both interesting and depressing. As a formerly incarcerated person, you also called the House of D, the New York City landmark for queer women and trans masculine. I think there’s a lot here that needs to be unpacked. So can you talk, I mean, this the idea of a prison of being kind of the central organizing space, although, to some extent, all of us know that’s true. We’ve been to prison, that it’s the central or a central US base for history. still seems a bit shocking.

Hugh Ryan

Yeah. So to answer that, I’ve got to pull back a little bit, unfortunately, with many questions, I have to go back to the 19th century, because I am pedantic and long-winded. So in terms of…

Joshua B. Hoe

You’re on the right podcast…

Hugh Ryan

Fabulous. In the 1870s, there’s a major conference held in Ohio to talk about prison reform, and particularly, to deal with women who are coming into the public sphere post Civil War. So both black women who are newly freed, but also white women who have taken up much more of a public space during the war, either because their husbands’ brothers and fathers were away, or because they themselves were participating in the war, for many reasons. After the 1870s Women’s the control of women, which had largely been part of the family before that, either the birth family, the family that owned enslaved you or the family, if you were a live-in domestic that employed and housed you, women’s justice, quote, unquote, was their domain, women were punished and detained inside of that after the 1870s. As they move into the public realm, that work has to go somewhere, right? And so these prison reformers start to try and take what is essentially an 18th-century system targeting the violent anti-social acts of white men and repurpose it into a system of social control. Right now, we’re no longer looking at actual violent acts. The idea of women’s justice that they come up with at this reformatory movement in the 1870s is that women need to be arrested earlier, over morals, right crimes against the public order, not violent acts, not theft, but intoxication, public disorder, venereal disease, drug use, prostitution, all of these things that are only crimes, quote, unquote, in the sense that they might, down the line, at some point, hurt a white man, right? That’s the idea of criminality that we move into. And this is not just a moral proposition, they began to think that they needed to incarcerate improperly feminine women, because not only were they a disruption to the public order, because they are smoking or wearing pants or refusing to go out with men, or ignoring their parents or skipping school, all these things that are not really crimes, right, but they’re disturbing the public order. And that disturbance in their eyes was directly linked to not being feminist, right? Because at this moment, in the late 1800s, there are really only two jobs a proper woman can have a wife or maid. And if she’s not one of those things, she’s going to end up on the streets as a prostitute. There is no other world. So the prison system to keep women from being incarcerated, and returning to prostitution or going into prostitution needed to make them feminine. That was what they thought. In fact, the first women’s prison that opens up in America says in their annual report, that their job is to retrain and remold incarcerated women to make them into the positions God intended this, wives, mothers, and the razor’s edge, right That is the idea behind women’s justice in America. And obviously, from that moment, it targets queer people. Because the rubric the essential nature of what it is doing is a forced feminization project, it is trying to make women into better women. And so from the very beginning, it targets people we today would see as queer for violations of gender for violations of sexuality. And that compounds upon itself year by year, by year by year by year, until, by the time we get into the early 1900s, we get this idea of Freudian ism that comes in right and tells us sexuality lives in the mind, not in the body, there is such a thing as homosexuality and heterosexuality, and the prison system is the one that teaches that to incarcerated women, right? Because where else are they going to learn new ideas about sexuality, certainly not going to be taught in schools, certainly not going to be taught to them in their homes, but the prison system and the courts, they are concerned about improper femininity. The improperly feminine woman is both a criminal and a homosexual in the eyes of the government. And the system teaches women this over and over again, the women and trans men that I see arrested in the earliest history of the house of D in the 1930s are told in court, that they are lesbian, and that what a lesbian is this information has to be spread, because it’s new, it’s different. It’s not how people thought about sexuality, gender, and queerness in the 19th century. So in this sense for women and other folks assigned female at birth, the courts and the prisons become the predominant vector for explaining modern ideas of sexuality. This is the same thing that the historian Alan Barra Bay writes about in regards to World War Two and men. He writes about how in that instance, the government teaches all of these single men about what homosexuality is through induction lectures that bring them into the military and then giving them same-sex segregated space where they can put those new ideas into practice, right? That happens for men and World War Two. But for women, it happens earlier, and it happens through the court system and through prisons. So prisons almost constitutionally, particularly ones for women cannot help but be centers of queer history.

Joshua B. Hoe

You’ve talked about this a bit already. But one of the themes of the book seems to be that a lot of the problems of prisons and jails were created by people who are purportedly trying to be of help. In this case, it seems like the path to hell was paved with good intentions. Yes?

Hugh Ryan

I think to a degree, I mean, we always have to remember that these people are reformers working inside a pre-existing system. So while I don’t agree with the direction they took the reforms in, oftentimes, if you look at what they’re actually asking for, like these were called Social feminists in the early 1900s, kind of similar to what we might refer to as white feminists or harsher for us carceral, feminists, reformers, feminists, they’re actually asking for a much bigger picture than what they ended up getting. Right. They have aims and goals that are far beyond just shaking hands with the carceral system, but they make a deal with the system. And the system only ever gives half measures, right? And it’s always the carceral half. So some of the folks that I follow, they asked for these big things like changing how women are treated inside of prisons and changing the laws around arresting women, but they also want bigger sentences for women, they want this system be able to hold them for longer. And yeah, those folks I think often go in the wrong direction. But I do want to make sure that we keep in mind that they are also working inside a much bigger system that they are working with. And while I don’t agree with these social feminists of that era, what they were looking for was much comp more complicated than what they got. The real problem is that they made a deal with a system that had no interest in those bigger ideas, and will only ever give them a half measure. And that’s what I tried to say to reformers today is that I think oftentimes, we have many of the same goals. But you are making a deal with a system that will never give you what you want

Joshua B. Hoe

As a formerly incarcerated person. One of the most bizarre experiences I personally remember was when like the warden would bring in non-incarcerated people for visits. So it was kind of like you felt like you were in a zoo. You talk about the women’s court back in the day, and even the Night Court today. And kind of the notion of this voyeurism and prison and pain tourism. Have you done any additional thinking about this? I mean, a lot of people do court watching for good reasons. But there seems to be this seems to be a unique form, for lack of a better term excess enjoyment from folks watching people suffer.

Hugh Ryan

Yeah, I mean, I think that the pain and suffering is still so operative today, right? The whole genre of true crime or watching you know, court cases on YouTube, that that still happens and there are things we can learn but also it’s a lot of it is about entertainment. Go Think back to the earliest parts of the house of deeds, the women’s court in the Night Court that you mentioned. Yeah. When those were created the Night Court in 1907, the women court in 1909, they intentionally set them up so that they would embarrass arrested women and show proper women what not to do. And so they did things like the women’s court had raked floors. So like stadium seating, you know, so that everyone had a good view. They made flyers advertising, how good the views were, and how exciting it was to come and court watch. The head of probation for the Court wrote that that was the most important thing the court did, not what it did for women who had been arrested, but rather what it did for watchers, right? Because already from the very beginning of the house of D, these are not people to be helped, right? They are lessons to learn from, they are dangerous to society, but they’re not people. And so the interest, the most important part is never going to be them. Right. The system is always about other people, not the incarcerated person. So that entertainment, of course, is what they see as the Merton part of it. And going back to what we talked about a little bit earlier about the connections between Greenwich Village and prisons, Greenwich Village has had a bohemian reputation since the mid-1800s. But it only takes off as a destination for tourists in like the late 19 teens 1920s. That’s when it becomes this kind of like bohemian slumming destination, it becomes very cool to go there kind of in the same way it becomes cool for white people to go to Harlem on slimming tours, all the books that write about cafe culture, and these slumming tours, put that around 1918 1919. That’s when all these cafes open up. By that point, rich people had already been coming to the village for a decade to watch women arrested in courts, the first tourist destination, that is Greenwich Village that makes Greenwich Village or the courts in the prisons, right? But that history gets disconnected. And instead, we just get this sudden, for some reason. Cafes start opening up and rich people start coming right doesn’t make sense until we bring the prison back into the conversation. But again, it just gets cut out and Greenwich Village becomes imagined as a place where a prison gets inflicted upon it not a place where prison creates the

Joshua B. Hoe

it’s also sort of a beginning point for kinds of surveillance…I didn’t know about something that I learned from the book is fingerprinting, I was not aware that fingerprinting had largely rolled out as a way of keeping track of sex workers. Am I getting that right?

Hugh Ryan

Yeah, yeah, you know, fingerprinting gets its start in France. And then it moves over here with a scientist named Henry P DeForest, who’s really one who pushes it in New York. And they want to implement fingerprinting because there was a previous kind of way of tracking quote, unquote, criminal bodies, what were called bear Tijan measurements, which did not work very well. And they had been developed on men. So they really didn’t work on women. At this time. They understood criminality in a eugenic way. By which I mean, if you were a criminal type, it was probably in your body, you couldn’t be fixed. And there were bodily typologies. Right? There’s this really hilarious moment where like the chief magistrate of New York and an annual report like 1927, is writing about to change the laws of disorderly conduct. And reformers on the outside conservative performers are looking at this law. And they’re really excited, because for the first time ever, they’re going to start tracking men arrested for soliciting other men. It’s the first New York City Law to concentrate on gay people. They see it as a way of tracking these criminal bodies, right? The court system sees it as a way of also tracking criminal bodies, people who are born bad and they write this whole thing about it, but they’re not talking about homosexuals. They’re talking about pickpockets, the Chief Justice of New York City, thought that pickpocket was a biological class that you were incurable, that you were bodily wrong, right? So this is the mindset they’re going into these people obviously mind,

Joshua B. Hoe

Kind of modern-day Tom Cotton like I mean, pre prior day, Tom Cotton’s because that’s kind of his take.

Hugh Ryan

Yeah, they believe that body your body is your destiny is your personality is who you are in a very deep sense. So of course, you have to track those bodies themselves. It just makes sense. If the body is wrong, you track the wrong body. So fingerprinting was this idea that they had that might work, but they needed to test it. So they decided to test it on women arrested for sex work, because there were many of them. First off huge numbers of women arrested for sex work, because at this point in New York State, arrest for sex work does not have to have anything to do with the exchange of sex for money. Sex work is simply defined as the common lewdness of women, any poor woman is an invitation to sex work, because again, remember, no woman can have any job other than white fur made. And if you’re not properly feminine, you’re never going to get those jobs. All that’s left for you is to be a sex worker. So if you are poor, you are invariably going to end up as a sex worker. So most women get arrested as sex workers regardless of what they’ve done at this time. So they have this large pool of Arrested sex workers. They want to start tracking fingerprints. They know that in the case of an arrest of a woman for sex work, it really means that she’s and that she is not going to be able to protest and that no one will protest on her behalf. So if everything goes wrong, if fingerprinting doesn’t work, work, then that’s fine. Nothing is lost in the eyes of the law. So they roll it out on these women, and they begin to track them by their arrest. And what really like blew my mind about this is that very soon after, they start to say, this is proof that these women are born bad that they cannot be made better, because what they find is that as soon as they’re able to track the fingerprints of Arrested sex workers, lots of sex workers, it turns out had been arrested before, they never stopped to think that this maybe has something to say about the system these people live in. Instead, they start to say, well, obviously, she’s born bad because she’s been arrested as a sex worker in three different states. Men who are not being fingerprinted at this point can get away from those prior arrests, right? They can establish a new life for themselves, but women can’t. And they use this as an excuse to go in front of the judges and start saying, No longer do we need to look at the case in front of us and the evidence in front of us. Instead, we need to look at that woman’s fingerprints, see what she’s done before, and then base our sentence off this idea that her prior record shows that she is bodily bad and can never be fixed, right? So fingerprinted becomes not only a way to track these women but a way to make that assumption by what you’re tracking them true. If you are arrested often, then you must be bad. And you are arrested often. So we’re going to track you by fingerprinting, and that fingerprinting is going to show us that you were arrested often. It’s this circular logic, and they roll it out on Arrested prostitutes. And then they move it into women arrested for abortions. And then gay men arrested for soliciting. And only after that, does it really start to proliferate out to general populace.

Joshua B. Hoe

And you see some more of that in like the Supreme Court case, Buck v. Bell, just kind of a notoriously bad decision that allowed sterilizations for several for having “several generations of imbeciles,” I believe was the quote from the decision. And part of this is also this notion that the state that the state can use moral panics to concoct justifications for incarceration, we’re certainly seeing that now with the aftermath of the dogs decision or sexually violent predator laws or not to say, in any way, shape or form, that there aren’t kernels or elements of, you know, that might have criminality that might appear in any of these places. But the way that they’re used is they’re constructed in such a way that it’s a much larger system, what are what have you gleaned anything from your research or through looking through this period? That gives you an insight into kind of, you know, we’re literally seeing, you know, people are again, trying to make LGBTQ plus people criminalize that behavior. We’re seeing that with the aftermath of the Dobbs decision. Is there anything you can draw from that, that you can kind of that experience can teach us about future? I know, that’s a big question…

Hugh Ryan

Yeah, no, you know, what I think is really important about this. When I look at the ways in which these kinds of laws target queer people, one of the things that became very obvious in doing this research is that many times, unlike what you’re talking about right now, but there was no sort of prima fashion moment where you were like, Oh, this is about being queer. There were some women who were arrested for things like sending the word lesbian through the mail, you know, or wearing pants, and there, you can start to see it. But a lot of these folks were people who were working class or in living in poverty, in many cases, like not even working class who were living in poverty, because their queerness had kept them from so many other opportunities. Their families had forced them out, they couldn’t get safe jobs, they couldn’t get education. And so they ended up on the streets, where then they were arrested for all of these other things that aren’t directly related to being queer, right, but are in part or in the end do over the long tail to that person haven’t been clear. So when I think about lessons for today, I am often thinking about, you know, we get these debates that are happening right now over that 10-year-old who had to travel across state lines in Indiana, to have an abortion. And you see these right-wing politicians who are coming out and saying, oh, no, no, no, that’s…the law would never be interpreted that way. That’s not you know, yeah, maybe you could see on paper that there’s wiggle room in it can be used that way. The law will always be used that way, right? Like if a law gives more power to the carceral state, someone will eventually use it to the fullest extent that is possible. Right? So when peoples try to minimize these laws, or with the don’t say, gay bill down in Florida, you know, they say, oh, no, this isn’t going to be used to stop, you know, married same-sex couples from talking about their partners or just playing rainbow flags. It’s going to be about grooming, it will never be about those things. Right. Once the law is in place, it will be used to its fullest extent to punish whoever the state decides to and so that’s what I keep in mind when I think about this a lot. That’s what this sort of history has taught me in terms of how the queer movement should be looking at criminality, generally, it’s about a lack of care, right? The prison system exists to warehouse those people that the rest of the system refuses to take care of. It’s not really about criminality, and so many queer people do not get cared for by the family are by the state. And so they end up in prison. That’s why we have that 40% statistic 40% of people in women’s jails don’t identify as LGBTQ because they are being arrested for being lesbians. 40% identify as LGBTQ because queer people are abandoned by their family and the state. And without that care, all of these other broken systems leave us vulnerable and without support. And once we have no support, once we are vulnerable, once we are mentally ill, or homeless, or without a job, once you’re living on the street, then the carceral system sweeps in and scoops us up. It doesn’t do it directly, because we’re gay. But we do end up there because we are gay. And so it’s that kind of longer-term thinking. I think for too long, there has been this kind of focus in the parts of the mainstream LGBTQ movement that do think about criminality. unjust laws that are on their face discriminatory write a law that says, a gay man can’t do this, or you can be arrested for dressing in this way, we need a much bigger frame to look at the criminal legal system in order to understand the incarceration of queer people.

Joshua B. Hoe

Yeah, I know, this played out for me in two ways. You know, there are probably more but two that stand out in my brain. The first one was, I was at a place called Mountain Road prison, which is now closed, but there was a trans woman there who had been incarcerated for decades. And one day, she sat down and just told me all, you know, basically the litany of terrible things that have happened to her and her 30 years in the male prison. And that had a pretty big impact on me. And the second one was, I had a friend who was gay at another prison. And he really wasn’t doing anything, but everybody knew he was gay. And one day, he just walked into the bathroom the wrong way, or someone took it, someone took it the wrong way. And basically, they beat up pretty badly. And so I saw how, you know, at least in male prisons, there’s a lot of unique, kind of horrible. And again, you write about a little bit in the book, even though it’s about the difference between men and women, women’s prisons, do, you want to kind of put that in context and kind of this notion of, you know, you know, I’m a cisgender, white straight man. So, you know, I probably can’t speak to it in the same way, you probably can or have done as much research on it, as you had.

Hugh Ryan

You know this is one of the things that came up, particularly in the sort of the 60s Chapter of the book. And it was through kind of listening in, I got to listen in through various informants of conversations between members of the gay liberation front and the Black Panther Party, who had been incarcerated. And what came up in those discussions over and over again, when you talk to formerly incarcerated women, particularly in that 60s, radical revolutionary period in the 70s. They’ll tell you that being incarcerated, gave them a chance to think about their lives and see connections between various forms of oppression, particularly in the 1960s, you get a lot of folks saying, being in prison, allowed me to see experience and interact with queer people and see the ways in which that oppression is the same as that that I might be receiving a J tool, that activist I mentioned earlier, when I asked her if there was ever an attempt to like segregate lesbians, she just laughed and said no, there were too many of us. They couldn’t do that, right? Because it’s 40% because the women’s justice system is looking for people. So there’s just too many queer people in women’s prison for them to be segregated. So for women who were incarcerated in that period, it became a chance to form connections to see all of these ways in which the work is related. A finish a core is in the women’s house of detention during the Stonewall riots. And when she gets out, she talks about how seeing the banners outside and meeting gay women in prison got her thinking about these systems of oppression. And she works for the next few years to connect the Black Panther Party in the Gay Liberation Front, along with her girlfriend who she also met in the house of D. So she finished court is having a conversation with the father of her son to POC, a man named Lumumba Shakur, and they’re doing this near the prison in a safe home in the West Village with some Gay Liberation Front members present. And they get into this conversation where a finished record basically says the same thing Jay Toole told me that being in prison allows her to see all of these connections and meet all of these people. Lumumba has a very different experience. In men’s prisons, there’s often what’s called a ferry wing, or these days, it might be called a trans housing unit, a place where feminine gay men, trans women, and some people arrested for specifically queer crimes get put for their safety. These are really complicated spaces. Some people on the abolitionists and activists that are really into them, some people really aren’t, I’m not going to kind of go into that, but they exist, right? And they present a place where from the members’ point of view and the point of view of many of the black men who are in the Black Panther Party that he’s kind of talking about. Gay men are either weak or effeminate and need to be protected by the very system that has incarcerated them, right? So in some ways, they seem in league with the state, or they are lying, straight acting, quote, unquote, asshole bandits, who will rape you? And he talks about the ways in which in the prisons he’s been in the system says, Yeah, that’s true, you should kill that man who tries to have sex with you. Right? So while telling them, all gay men are the feminine ones we keep in this special place, because we care about them more than you. There’s also a wide pool of men having sex with other men who the system says you need to kill each other to prove that you’re not gay. Right? So the system taught those men that gave people were either weak and in league with the state, or lying rapists who you needed to kill. And that’s very different from what the prison system taught to the women who were incarcerated at the same time. So we see a way in which the structures of incarceration, the idea of what they do, right, the reason women are getting arrested leads to a different population in the prison. And that population treats people differently. So then on the outside, those women have a very different idea about sexuality, and cross movement organizing for men, the system creates blocks and walls and says, You cannot organize together, you are completely different, you should kill each other.

Joshua B. Hoe

Let me read this passage from the book and get you to react. Because it really struck me that you said this in a book that is often about prisoners aside of connection and resistance. It feels more intellectually honest to approach sexual orientation as a limited, useful, but ultimately unstable and unclear category of existence, like political parties, or sexual orientations or cloud formations, indistinct at the edges, and always shifting, yet discussed as if everyone sees the same vision in the midst. This is fascinating because the importance of queer history and connection and identity seems really important, both in prisons that you talk about and at this precise moment in history. But what you’re saying there is also I think, unquestionably true. Can you kind of navigate the tension between those two things for if maybe you don’t see a tension?

Hugh Ryan

Yeah, I mean, I think for me, when I think about that section of the book, what I’m trying to talk about there is this idea that is this can be for sexuality, but it can also be for gender, right? Think about the current debates around what is a woman right. Which parts of the label do we say are constitutive? What matters? What is essential? And we all have different arguments about that. And I think the truth is, for most of these labels, no one part is constituent, right? It’s a preponderance of the evidence, right? That allows us to see the shape of a lesbian or of a woman. And then when you dig into it, you’re like, Well, I don’t actually know what my chromosomes are, right? So we don’t actually know what the answer is. Some things don’t matter that much. This matters, I think, to me most right now, because what is happening is, we are seeing a shift in those terms, and in those identities, and that shift is happening all over the place. I often joke that I’m old enough to remember when the book transgender warriors had the subtitle, from Joan of Arc to RuPaul, neither of whom would today largely be considered transgender people. That was just the 90s, right? These change ideas, these concepts, they are changing all the time. And we’re going through a major moment of change in what those concepts mean, right now. And I think that that is hard for us. When we look at prisons or other single-sex spaces, though, I think what we really start to see very quickly is that this hard binary of sexual orientation that you have heterosexuals and homosexuals and a fuzzy gray area where maybe there are bisexuals, but we’re not particularly clear on what’s happening there. But we have these two big groups, and we stay in one for our entire lives. And they are the first determiner, right? Everything about our sexual orientation, our desire, our relationships, our sexual practices, it starts with sexual orientation. That’s the limiting factor. And then from there, you make all these other decisions about who you’re attracted to, you go into single-sex spaces, and that just falls apart. What you start to see is that there are some people for whom Yeah, sexual orientation is the hard line. If they are straight, they will never voluntarily participate in sexual activity with another person of the same sex, they will never feel this desire, they will never have these men. But for many people, what you start to see in prisons or in colleges or on ships, is that sexual orientation is real. Sure, yeah, maybe you are oriented towards people of the opposite sex. But that is not the sole determiner of the kinds of desire you can have the kinds of relationships you can have. For some people. I think sexual orientation can change over life. And I think for some people, sexual orientation doesn’t matter as much as other aspects of experience. And we’re seeing people start to define that right I think people get really mad about all the new terms around sexual orientation and gender identity that people are experiencing and experimenting with right now. But I think things like CPO sexual, are really trying to index what it means to have an attraction that isn’t necessarily grounded in sexual orientation first, which is different from bisexuality, which is an orientation towards both sapiosexual says, I may have an orientation towards one thing, or another thing or both things. But what actually makes the determination is knowledge and personality, right? That’s a different form of sexual orientation than the one we talked about classically. And it becomes very clear, when you look at single-sex spaces, how common that is, for all of us, that there just are a large number of people whose lives are not primarily at all times determined by the binary of heterosexual homosexual. So when I looked into the experiences of these women and trans men and non-binary folks in the prisons over and over again, I couldn’t feel comfortable saying, oh, this person was really a lesbian, but never news until they were in prison, or this person was really straight but was forced to have, you know, lesbian sex because they were so lonely for the two days they were in prison. No, none of that makes sense, right? That’s not what’s happening here. It is something beyond sexual orientation. And I think we have to get used to that, I think we have to start to say sexual orientation is not the only part of our desires and our relationship.

Joshua B. Hoe

You know, we’ve talked a bit about how prisons can be a site of resistance of space for collective organizing, for understanding for history. But the flip side of that, that you raise a few times in the book is this kind of abandonment that people face during an after incarceration either through lack of attention in programming, or from essentially being released with a five cents and a handshake. You know, if that you also talked about housing discrimination in the book, the more cynical among us, would probably suggest that we build the systems for failure and not for success. I tend to be a little bit in the middle on a lot of this stuff. Do you have any thoughts about that?

Hugh Ryan

Yeah, I mean, I think that the prison system is inherently about care and abandonment, because it’s not about criminality. It’s not it’s just, it’s about who has been abandoned by the state who needs care that is not going to be provided anywhere else. I don’t. For a long time, before I did this research, I would have told you that the prison system was broken, right? That it was about justice, and it was about reform, and it wasn’t working properly. But when I dug into this history, decade, after decade, after decade, you just see everyone involved from the judges, to the administrators to the city government, to the women incarcerated to the social workers working with them, everyone says most of these people should not be arrested, most of them need other services, we cannot help them in the prison, we do not help them in the prison. And they are worse when they get out. And then they get arrested. Again, if that is true, at every stage, if it has been true in Liberal administrations and conservatives, if it continues to be as true now as it was in the 1890s, then the system isn’t broken, right? The system is simply doing something different than what we have been told is doing. And once I started to see that, once that lens opened up, for me, abolition was the only paradigm that made any sense, because it was the only people looking at it and saying this is what the system is for this system is not a broken justice system. It is a monstrously efficient drain, that puts all the people that are actual broken systems of welfare and housing and mental health and physical health and education and job training. All those actually broken systems, the people they don’t care for, we need to put them somewhere. And the place where we put them is prison, right? That is why it cannot change. Because you cannot reform something until you understand what it is doing. And reforms about justice and rehabilitation have little to no effect on the criminal legal system and on carcerality. Because it will be overwhelmed by the other broken systems, who will continue dumping people into prisons, which forces the system right back into its old shape, right, no matter what reform you make. All these other broken systems depend on the prison acting as a drain for people, the government refuses. And until that changes, you cannot change a prison.

Joshua B. Hoe

You know, I think earlier you talked about something being pedantic and long-winded I’ve kind of been asking questions, perhaps too much in a thematic manner. But this book is also a lot about stories, and about personal narratives, and about those kinds of relationships, people whose stories might not always have been shared in the past, and this book holds them up and tells their stories. Can you talk more about how that part you already talked about how you found the stories, but kind of how you’re you arrived at who to talk about and any of the stories that might be on your mind? You’ve already talked about a Phoenicia core, for instance, but anything else that you want to raise up?

Hugh Ryan

Yeah, my process is usually like this. I will identify the archives that I’m drawing from, in this case, largely the women’s prison Association, then I usually spend, I say, for one year of writing, I spent four years researching, the vast majority of my work is research. And I will swim in those kinds of primary source documents, I tend not to read too much tertiary material, analyzing what I am going to analyze until I’m late in my process because looking through other people’s eyes too much, I see what they see instead of seeing what’s there. So I try to go into the primary source documents as much as I can and start to establish just a sort of a master map, almost I start, I’ll say, like, you know, for instance, in doing the research on this book, somewhere in the late 50s, I started to see over and over again, references to being drugged in the house of detention to people who were detained, being like zombies to all of these things that led me to say, okay, something happens. And then I can 50 Something happens here that was not happening before. And what I eventually found out it was the 1954 discovery of the Thorazine in France, which comes over in 1955, and almost immediately starts getting used in asylums and spreads from there to prisons, where it gets us it endemic over drugging levels at the house of detention.

Joshua B. Hoe

That’s sort of ironic that you’re incarcerating a lot of people for drugs, and then immediately drugging them up so you can control,

Hugh Ryan

It makes you wonder who the biggest dealer in the country is. It’s usually the jailers, I find they are the ones pumping these one invalid drugs, and then putting them right back out on the streets. But I swim in the data of sort of find those moments, right? And then I construct a skeleton of the book, which sort of says, what is happening with the prison over the course of these years? What is happening with the city over the course of these years? And what are these major moments of change that I need to explain or understand, once I have that structure, then I go back to the research where I’ve been cataloging every single person who I come across, who I think might be useful to tell a story through, and I say, Who is the one or one person or the two people who best physicalize embody this particular bit of the story I need to tell right? Because I think as a reader, we need physical details, we need to be able to see the world, we need to experience things and have feelings and emotions in order for this history to matter. And those feelings and emotions live in the experiences of actual human beings, having lives that interact with the history we need to tell. So swimming it for a long time to understand the general trends, then go back, explore those trends to understand what they mean. And then go back again to figure out which individual people will humanize those stories. So my book is really a collection of individual profiles that I’ve arrived at, by deriving from many, many more profiles, what mattered and then asking, which is the best profile to explain this to someone who doesn’t know, it’s a very long process.

Joshua B. Hoe

So we’re kind of getting toward the end. And I think one thing I really think it’s important to hold up is that I had never really heard the connection before. But most everybody who is even remotely familiar with kind of queer politics, is aware of Stonewall, and most people would not connect that to a prison. And that is probably unfair, at least that’s and sad in a lot of ways, at least from my reading of the book. Do you want to talk a little bit about that? Because I think it was a really important part of the bar.

Hugh Ryan

Yeah, yeah. Stonewall was about 500 feet. The bar was 500 feet away from the prison, Christopher Street, the street that Stonewall was on, which is like the heart of you know, gay Greenwich Village, dead-ended into the prison. The women who are incarcerated, the house of D, many of them could see what was happening during the Stonewall uprising. They could smell it, they could hear it, and they held a riot all their own. They set fire to their belongings, and they threw them out the windows while chanting gay rights, gay rights, gay rights. People in the crowd remember seeing this right? But the story has gotten cut down to leave them entirely out of it, even though you just have to like, I was interviewed by this guy, Jeffrey Masters, a really great podcaster. And he said it’s like you just turned the camera a little bit. And I was like, yes, that is exactly it. If you look just the tiniest bit to the right, you see that the picture of Stonewall is much bigger than what we have been told. And in fact, after the protests, so Stonewall Riots go for days afterwards, local organizers, gay activist, older gay activists held a community meeting to try to channel this new young rebellious energy towards action. And folks who had been involved on the ground with Stonewall at the bar in the first protest and back on the subsequent nights, folks like Jim fra and Martha Shelley said, we want to protest the prison. They recognize that the prison was a source of queer oppression. And they wanted to purchase specifically in support of the Black Panthers who are currently there, Afini Shakur, and Joan Byrd. And the older activist said no, they refuse to do it. And so those younger activists actually left that meeting and announced they were forming a new organization, which they called the Gay Liberation Front, which would become an incredibly important moment in queer politics. They then went and protested the prison as their very first action and continued to protest the prison working with the Young Lords and the radical lesbians, and the Black Panthers and the Youth Against worn fascism. And all of these other radical 1960s organizations, they came together and protested the prison from Stonewall till the day it closed, there were other riots outside of the prison that are forgotten today, look up the 1970 Haven riot, for instance, there was a mayday right or no Women’s Day, International Women’s Day riot outside of there by feminist groups in the 1970s. There were all of these actions happening in Greenwich Village as a center of activism, because of the prison directly connected to what had happened that night. And Stonewall, when we talk about the origins of the Gay Liberation Front, it is as much the prison as it is the bar, but we leave off half of That’s right. And I think it is so important. You would think that if there was any moment in American history, there was nothing more to learn about it would be Stonewall, and if there was any place in American history, there was nothing more to learn queer history from it will be Greenwich Village, the fact that most of us do not know these stories that I didn’t know these stories, even as I started researching them, I think tells us how little we actually know about queer history right now. And how biased what we do know is.

Joshua B. Hoe

As I mentioned before, as a heterosexual person, I was a bit worried that I might not be asking questions that our LGBTQ plus listeners might have about the book. So I asked a few queer friends who are reading the book if they had any questions they would like to ask. This was the question that I got in response from my friend Natalie Holbrook a bit long, but bear with me, my main question, reading the book, how do we get mainstream queers to care about the stories illuminated in the book and the ongoing stories of queer women and gender nonconforming people? How do we move the discussion even more away from the academic discourse to ground-level organizing, if it’s easy for neoliberals to swallow LGBTQ politics, like light, gay marriage, and the workplace discrimination against non-conforming folks? But what are what about standing up for sex workers’ rights? What about the Dems, caring about the reality that LGBTQ homelessness leads to criminalization of the same youth and lands young people and young adults in jail and prison more readily?

Hugh Ryan

That’s a big question. I have small answers. Unfortunately, as I tell everyone, I am a writer and historian, not an organizer. But I do think that in that particular world, into the world of queer politics, which is the world I very much live in, in a queer world, that’s it’s very much my world, I see my work as someone who cares about these issues, who is not formally incarcerated, who has the space and freedom to talk about these issues as calling in those people, right? If someone is going to tell me that they are a Democrat, or that they are a gay person, I know that we already have some kind of commonality that I can work from, and it is my job, if I believe in these things, to bring those people closer to my positions, but that work is frequently one on one. It is small scale, it is long, it is hard, it is painful, I think we start in places like our family, our friend groups, our work relationships, start with the people you already know, and bring them in towards you, and help educate them, teach them talk to them, like they’re people with real concerns, right? Don’t talk down to them. But don’t get frustrated, too, right? Because when we get frustrated, and we turn off from those people, then who is left doing the work to convince them to come to us, the only thing that’s left at that point is to hope that somehow their eyes suddenly open to a different kind of morality, which I think those kinds of revelations happen for very few of us, without someone guiding us without someone taking us by hand, and bringing us to new thoughts and discussing them closely, deeply in an emotional way where that person can feel vulnerable and can say some shit, that’s probably going to be fucked up, or at least like really disturbingly articulated, even if the heart of it is good. Those spaces they are, they’re not on Twitter, they’re not in community board meetings. They are not when you’re fighting for a law in the street. Those spaces are at home, they’re in the bar. They’re at family reunions, they’re in the classroom, right? Those are the moments where I think we need to do this work, those of us who care need to bring the people who are part way there further along with us. And we need to clarify that the systems we are opposing are not the people inside them, right? That we still can bring those people in our direction. And we do not give up on anyone. Right? We have to keep that movement going. And then the system can be burned to the ground. I think that’s the line for me. Right? And I think that we need to always remember that when we are talking about systemic level changes, any reform that strengthens the system, no matter how good it looks in the short term will be used against us, if we are actually going to get to abolition, all of our reforms must be conscious steps towards it. And I do think we will need reform along the way, right, we can’t just jump to abolition, I don’t think it will work. And also I don’t think would ever happen. But every reform we get, we need to consider whether it will help. For instance, this new plan for like a feminist jail, where the bars are pink, or whatever it is that they’re pushing, I don’t think that’s going to get us where we need to go. That’s not the kind of reform, I would suggest supporting if you are interested in getting more mainstream LGBTQ people thinking about these issues, but I think talking to them about the fact that 40% of the people incarcerated in women’s prisons today are queer, and helping them think through why that might be, and how that might change the way we look at the carceral system. That’s where I think, at least for me, as someone who’s not an organizer, and it’s not in that part of the world, that’s where I think I can do.

Joshua B. Hoe

My friend Amanda Alexander always talks about the power of dreaming big, and of having freedom dreams. And I usually ask a question about this. But your book actually talks about the concept of freedom dreams, you suggested that freedom dreams are always collective. Can you talk about this and the history a little bit, and some examples, maybe a freedom dreams you might be excited about? Although I think you just kind of didn’t talk?

Hugh Ryan

Yeah, so I, you know, the kinds of freedom dream and free flow sorry, the concept of freedom dreaming, I was first introduced to through reading the work of tourmaline, who is an incredible artist, activist, abolitionist, queer historian, she’s kind of like, and she writes about it in vogue. And she’s talked about many, many other places. But this idea that freedom dreaming is a collective process by which marginalized compete people can together imagine a life beyond the sort of like, patriarchy, the SIS hetero, ableist, everything, everything, everything patriarchy because we can see in our commonality, the ways in which the lies that are told about us are not true, that we are not evil, or alone or crazy, or inherently inferior. And that that that whole collective imagination, is what has enabled queer people, in general, to see ourselves as equal, it underpins so much of the queer movement, you read about these, like early queer recognized leaders, folks like Frank Kaminey, and barber Giddings, and they do really important work, right. But one of the things that always gets said is like, they had the idea that like gay people weren’t bad, but you read their bios, and what you learn is that they went to a bunch of bars. And in those bars, they met a whole lot of gay people. And there, they learned that they were equal. And then they brought that thought, to the political organizing or to well-heeled political activism. But they learned that in working-class spaces, that were not those kinds of political activist spaces, they learned it from groups of everyday queer people meeting together, living lives and saying, We are not this awful thing that the system has told us we are right. And that same kind of freedom dreaming happens in the Black liberation struggle. It happens, in fact, in all liberation struggles, but it is it through the Black liberation struggle that I think it got named, codified, seen as a way of doing this work, Freedom dreaming the term like I think that we need to learn from looking at the vast, long experience of black liberation struggles in America, how they connect with and are the same as queer liberation struggles, and how they disconnect from queer liberation struggles and can inform queer liberation struggles, right? It’s not like they’re the same. And it’s not like they’re opposites. But there are parts of each that we can.

Joshua B. Hoe

I know, we’re here to talk mostly about your book. But I also like to ask people if there are any criminal justice-related books that they liked, and might recommend to our listeners, favorites that you might recommend,

Hugh Ryan

Gosh, I always panic when people ask me for book recommendations, because immediately it’s like, my mind falls out of my head, and I cannot remember anything.

Joshua B. Hoe

But I’m sitting in front of a bookshelf full of all my books. So I can just turn around if needed.

Hugh Ryan

I’m currently like, very slowly, unfortunately, reading “The streets Belong to Us” by Andrei Fisher, is that right? I have. Well, anyway, the streets belong to us. Really incredible book that I wish my book had come out like a year later so that I could use a lot of her theoretical and historical analysis in my book, I just feel like we’re talking about the same issues the same work. And it’s about sort of the carceral attack on women, particularly lower class women and black women and queer women on the street level is that the kind of like racialized gendered policing, and I just think it is really just an absolutely brilliant book. And then, my favorite, the one that I recommend to everyone, for the last year has been Mariame Kaba’s “We do this Until We Free Us,” which I think is not only absolutely brilliant, but it’s so readable, right? That she takes complex and intense issues and makes them so that everyone can understand them. And also so that you feel something when you read it. I love academic work, and I love historical work, but oftentimes I don’t feel As much as I want to, and I read those things, and I think feeling is often what keeps me going and keeps me in the struggle. So yeah, those are two that come to mind right away. “We do This Until We Free Us” and “The Streets Belong To Us.”

Joshua B. Hoe

I love Mariame Kaba. She’s one of my favorites. Is there any particular place you’d like for people to find your book?

Hugh Ryan

Local bookstore, that’s my number one favorite, or your library. And if they don’t carry it, ask your library to carry it, lots of libraries, listen to their patrons. You can also buy it everywhere else. You know, there’s, there’s lots of places in that big website that I shall not name, it has the book.

Joshua B. Hoe

I always ask the same last question. What did I mess up? What questions should I have asked, but did not?

Hugh Ryan

I don’t think you did. I think we had a lovely conversation.

Joshua B. Hoe

I always like to ask that in case there are things that people are wanting to talk about that I didn’t get to.

Hugh Ryan

Um, no. I mean, I think the one thing that I’m really happy about honestly, in doing this interview with you is that I wrote the introduction of the book as a really a look at abolition and queer politics because I think you could have read my whole book. And while you would see threads of it, it’s not directly in the book. But this is the frame, I think, that I want people to take to the book. And so I’m really excited to do this here. When I’m talking with historical places, a lot of times I bring up the abolitionist lens, but that you really, I mean, that’s the frame that this podcast is looking at it through. So that I think is what matters so much for me. So I’m just really happy to have had the chance to talk to you and through you to your listeners.

Joshua B. Hoe

I really appreciate you taking the time. Thanks so much.

Yeah, of course, have a great rest of your day. You too.

Joshua B. Hoe

And now my take, I originally wanted to do this episode, because there’s been such a horrible backlash against LGBTQ plus people and LGBTQ plus rights over the last year. And I’m hopeful that our discussion address those concerns, especially for people who are or could be incarcerated. But I learned so much more about how the history of incarcerated people is and often should be considered essential to how history and LGBTQ plus history are shared and taught our stories as much as any others, our history. And no matter how many times people try to tell us differently, the things we do after arrest and incarceration are frequently important to accurately sharing the history of our nation. In addition, when I started this podcast, and when I started my activism, I was committed to working to help every single person in prison, not just certain types of people are the types of people with certain offenses. I tried to look at people who are or who have been incarcerated as one family. And it’s with that focus that I tried to do this work.

As always, you can find the show notes or leave us a comment at decarceration nation.com. If you want to support the podcast directly, you can do so from patreon.com/decarceration nation. For those of you prefer a one-time donation, you can now go to our website and give a one-time donation. Thanks to all of you who have joined us from Patreon or who have given a donation. You can also support us and other non-monetary ways by leaving a five-star review from iTunes or adding us on Stitcher, Spotify, or from your favorite podcast app. Special thanks to Andrew Stein, who does the editing and post-production for me to an ASBO for helping with transcripts and social media images, and Alex Mayo who helps with our website. Make sure and add us on your social media and share our posts across your networks. Also, thanks to my employer safe and just Michigan for helping to support the Decarceration Nation podcast. Thanks so much for listening to the Decarceration Nation podcast. See you next time.

Decarceration Nation is a podcast about radically re-imagining America’s criminal justice system. If you enjoy the podcast we hope you will subscribe and leave a rating or review on iTunes. We will try to answer all honest questions or comments that are left on this site. We hope fans will help support Decarceration Nation by supporting us on Patreon.