Joshua B. Hoe interviews Judge LaDoris Hazzard Cordell about her time on the bench and about her book “Her Honor.”

Full Episode

My Guest – Judge LaDoris Hazzard Cordell

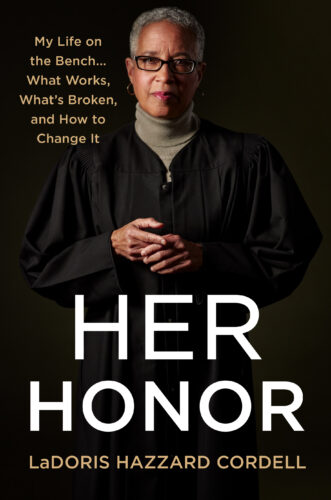

Judge LaDoris Cordell is a legal commentator and police reform advocate who is a frequent guest on major news outlets. She was the first African American woman jurist in Northern California, a position she held from 1982 to 2001. She is the co-founder of the African American Composer Initiative and California Parks For All. She is also the author of the book “Her Honor: My Life on the Bench…What Works, What’s Broken, and How to Change It.

Watch the Interview on YouTube

You can watch Episode 123 of the Decarceration Nation Podcast on YouTube.

Notes from Episode 123 Judge LaDoris Hazzard Cordell

Judge Cordell recommended the book “Letters to the Sons of Society: A Father’s Invitation to Love, Honesty, and Freedom” by Shaka Senghor

You can find Judge Cordell’s Book, “Her Honor” wherever books are sold.

Visit Judge Cordell’s website.

Full Transcript

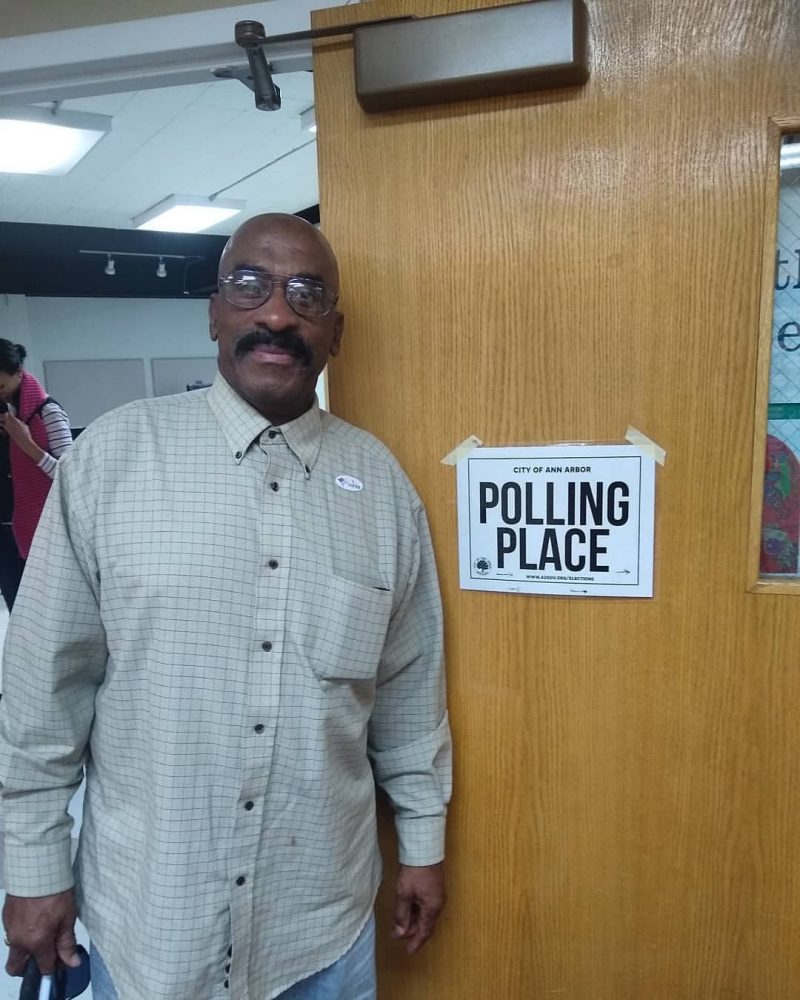

Joshua Hoe

Hello and welcome to Episode 123 of the Decarceration Nation podcast, a podcast about radically reimagining America’s criminal justice system.

I’m Josh Hoe, and among other things, I’m formerly incarcerated; a freelance writer; a criminal justice reform advocate; a policy analyst; and the author of the book Writing Your Own Best Story: Addiction and Living Hope.

Today’s episode is my interview with Judge LaDoris Hazzard Cordell about her time on the bench and about her book Her Honor. Judge LaDoris Cordell is a legal commentator and police reform advocate who is a frequent guest on major news outlets. She was the first African American woman jurist in Northern California, a position she held from 1982 to 2001. She is the co-founder of the African American Composer Initiative and California Parks For All. She’s here today to discuss her book Her Honor, which reflects on what she learned from her years on the bench. Welcome to the Decarceration Nation podcast, Judge Hazzard Cordell.

Judge Cordell

Thank you so much. And I’m glad to be able to talk to you.

Joshua Hoe

I always ask the same first question. How did you get from wherever you started in life to becoming the first African American woman jurist in Northern California?

Judge Cordell

I’ll see if I can give you the abbreviated version of this. And thank you for asking. I was born and raised on the East Coast, just outside of Philadelphia. My maternal great-grandmother and great-great-grandmother were enslaved. And after emancipation, they ended up in North Carolina. We’re not clear where exactly they were enslaved. My mother, her family came up in the great migration in 1940. This was right when the Great Depression, the Depression hit, they lost everything and they ended up in Pennsylvania, my father’s mother, and he raised her alone, single mom, from the Great Migration went from Virginia, up to Rhode Island. And so my father was born, and then came back to Ardmore where his mother had family members. Both of my grandmothers were the help. They worked, cleaning and taking care of houses of wealthy white folks on what is called the Main Line, and it’s just outside of Philadelphia and named for the big train, the main line that ran along the east coast, and the main line in Pennsylvania. It’s the homes of the Heinz families, the DuPonts, and just old money in this country. And my family members and those with whom I grew up, were the help and provided services for the folks who live on the other side of the tracks. My parents ran a dry cleaning business in the black community in which I grew up in Ardmore. And a lot of their clients and customers were from the main line. And that dry cleaning business supported my family. And my parents ensured that their three daughters – I’m a middle – would definitely go to college. So we all attended college, I went to Antioch College in Yellow Springs, Ohio, and at Antioch, that’s where I finally made a decision that I wanted to go into the law, because I ruled out the things I wasn’t good at, which is math and science. I was kind of left with the law. I had no thought whatsoever about being a judge. I just knew that, given the activism of my parents, they were community organizers, we learned by example, just watching them, my sisters and I, I knew that I did want to do something to give back. And I also needed a profession where I could be independent and take care of myself. So there was the law. I ended up going to Stanford Law School and came out to California. I had a big afro, we’re talking now the early 70s. And I was the only black woman in my law school class. There were no professors of color. And there were no female professors. So just white males at Stanford at the time. And I was I kind of, I felt like a fish out of water. And it was a very competitive environment, but I managed to make it through and during that time I was there, they brought in the first female professor, Barbara Babcock, and their sense, of course, for more students of color. And so when I finished Stanford, I then opened a private law practice in East Palo Alto. So, Palo Alto, that’s Silicon Valley, that’s the home of Facebook, Google, all these folks. East Palo Alto was literally on the other side of the freeway. And at the time in the mid-70s, when I finished law school it was a predominantly black and brown community, low-income. I opened a law practice there because I couldn’t get a job. I applied to major law firms in the Bay Area. And just basically they weren’t hiring black women. So in the way of my parents, who make a way where there is no way, you figure it out, and I decided to open a law practice with the help of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, that had what are called Earl Warren Fellowships that helped subsidize my law practice for the first four years. I practiced law in East Palo Alto, then a door opened. I decided to step through, and that was to be the Assistant Dean at Stanford Law School. The primary job, it was an administrative job, was to recruit students of color to come to Stanford, I did that. And during that time, as I write in the first chapter of my book, Her Honor, I was bitten by the judge bug, that I got this phone call from a stranger, and it just changed my life. I got a phone call from a man named Mark Thomas who was a white guy. He was a judge on a court in the county in which I lived and still live. And he said, Look, I’m trying to bring women and people of color into this program we have at the court, it’s a judge pro tem program where you can be a judge for a day, and preside over a small claims case. And small claims are the Judge Judy cases, right? No lawyers, thank goodness. And so it’s just litigants, you know, suing each other over not large amounts of money. So I said, Sure. That’s wonderful Judge Thomas, and he put me on the list. I forgot about it. And then a few months later, I get a phone call, my name has come up on the rotation. I go to court, I preside over a case. And that changed my life. When I drove home that day, after that experience, I knew that the next thing I wanted to do was wear a robe. I liked wearing that robe, I’d like to be in a position to make decisions for people who could not work things out themselves. And what makes the case so stunning is that there were only three people in the courtroom that day, the two litigants suing each other, and me, and all three of us were black women. And it was just stunning because there aren’t many black folks who live in this particular area where the court was. So all I can say as a little teaser, to those who haven’t read my book, the case was all about hair, H A I R, about hair. And it really changed my life and sent me into the world of judging.

Joshua Hoe

I remember that part of the book very well. And it’s pretty amazing. And I do have to stop you for just a second, though, because you said something earlier, you said that you weren’t very good at math or science. So the only other option was law. Are those the only three options?

Judge Cordell

If you want a profession where you know, you can make some money, so I’m sure there were other things. But I decided that this was one way where I could make a living, and still not have to do math and science. And lo and behold, I was wrong because when I ended up on the bench, and presiding for example, in family court, which I write about in the book, I have to figure out tax issues for couples who are divorcing and figuring out the child support. And so here I was again and didn’t really get me all away from it.

Joshua Hoe

Before we get to the more serious stuff, I don’t want to entirely skip over one part of the book that you only briefly refer to. You are an artist and at one point even put out a calendar of your cartoons for charity that both did quite well and got you in a little bit of trouble. How did you get into cartooning and art?

Judge Cordell

Sure, and it got me in a whole lot of trouble. And I do write about that in the book in a chapter called Bad Judges. So cartooning. So art has always been a part of my life. I don’t know who else in my family before me did artwork, but I loved drawing cartoons. And at our home, I would do chalk, sidewalk chalk designs. And I got to do more serious artwork when I was in college. And again, it was just really a side thing for me, a way for me to just relax. I’ve never had an art lesson. And if anyone were to go to my website, and it’s just judgecordell.com, you can see my serious artwork. And I have had art exhibits, which are charcoal. And then you can also see the cartoons you’re talking about because they’re legal cartoons, where I drew a picture and you had to guess what the legal term was, but they’re very concrete. And it was these legal cartoons that I drew. And because I doodled at the bench, believe it or not, judging can sometimes be a little boring, and to keep myself awake, you know, when you’re hearing your umpteenth Drunk Driving trial. So I would doodle and that’s when I got the idea to try to draw legal terms and donate them to a nonprofit that raised money for lawyers who represent kids.

Joshua Hoe

And I see some music stuff behind you; I think you’re also a pianist. Is that right?

Judge Cordell

That’s correct. And I do play the piano and as you noted, a co-founder of the African American Composer Initiative, where we bring the music of black composers to the world and put on an annual concert, and again, on my website, there’s a link to that organization and you can actually watch and listen to the concerts that we’ve performed over the last 10 years.

Joshua Hoe

Well, we’re about to have the first African American woman appointed to the Supreme Court of the United States. You talk in the book about the importance to yourself and to the community, how important it was for you to be seated as a judge. What can you tell us about the importance of people of color, women, LGBTQ plus people becoming judges? And what do you think this Supreme Court appointment will mean, for the perception and credibility of our system of justice?

Judge Cordell

So in court, there would be an objection, and I would say, compound and complex question.

Judge Cordell

All right. And I love it. And I’m delighted to answer, let me focus,

Joshua Hoe

I tend to do that sometimes, I’m sorry.

Judge Cordell

I love it. Do not apologize. So just generally talking about the judiciary, it is so important that the judiciary be representative of America. Why? Because if you have a judiciary that looks like the people who come into the court, those people are more inclined to feel they have a stake in the system and to trust the system. And I really believe that. I don’t care where you are in the political spectrum. If you’re far right, you’re in the middle of far left, I don’t think there’s any argument that anyone can have that inclusivity is bad. Inclusivity is good, it’s a good thing. And the more inclusive we are, again, the more trust there is, the more people care about the system. So it was very important when I came on the bench, as you noted, the first black woman, we’re talking 1982, the first black woman to be in Northern California, on the bench. And it was a shocker to some people. Particularly when I walked out, I could just see people saying, well, now wait a minute, that’s not what judges look like, because the norm was white male. So it is so important that we have trust and belief in our system, the less diverse it is, the less trust, and the less people have a stake in it. So now if we look at the US Supreme Court, alright, so we’re talking 233 years, 115 different jurists appointed, and of the 115, we’ve only had three people of color., two Black, one Latino, we’ve never had an Asian American on the court. And we’ve only had five women. So the norm – and no one has really been upset – the norm has always been white male, and people are having conniptions. Because President Biden has said, I’m going to appoint a black woman, people, just some people just going nuts behind this. Well, why can’t he just appoint, just say he’s going to appoint someone who’s qualified? And you know, the answer to that is, and this is what I said when I was appointed, because I got told, Well, you just got appointed because you’re Black. And my response is and continues to be, I’d rather be appointed because I’m a black woman, than not be appointed because I’m a black woman. But the bottom line is that there needs to be a Supreme Court that looks like America. And that’s exactly what Biden has said. And other presidents have done this all the time. There was the Jewish seat. There was the Southern Democrats seat, we had Reagan who said, I’m appointing the first woman and you know, the world didn’t end. So. You know, the court has always been, the Supreme Court has always been, the selection of the justices is about identity. It’s about politics. And it should be about inclusivity and representation. So I am thrilled that we will finally get a black woman on the court. And a final thing just about that. The US Supreme Court works by consensus. They have what are called conference meetings, where the justices sit together with their clerks, and they discuss weighty, important legal issues. And it is just critical that different viewpoints be at the table when they are discussing these issues. And I think it was Sandra Day O’Connor, who actually said that when she was sitting in conference meetings, she would look over at Thurgood Marshall. And sometimes he’d have a little twinkle in his eye or he would nod. And she also said he would sometimes tell stories that informed me and sometimes changed my perspective in looking at the legal issues we’re considering. So it’s so important to have that plethora, that variety of perspectives at the table. When you’re at the US Supreme Court, so long overdue, and I’m looking forward to whomever it is he chooses.

Joshua Hoe

One of the things I really enjoyed about the book is that in a sense it is like a personal struggle. And there’s a lot of issues that it seems like as you’re writing, you’re almost coming to grips with in a way. And at one point in the book, you say that by simply donning the robe that you knew you lent legitimacy to the system that disproportionately targeted people of color. You’ve talked about the importance of being a judge and being that person, but there’s also some tension for you there. How did you navigate that? Can you talk about how you navigated that difficult terrain?

Judge Cordell

Joshua, this is such a good question. It was very difficult for me, you have wonderful insight because as I was writing this, I knew that if I was going to write a memoir, you don’t want to waste your reader’s time and not write honestly and truthfully, even though the truth may be pretty brutal. So yes, it was hard to write this. And I’m glad I did. And thank you for pointing it out. So there’s tension, there are pressures and tensions when you are first, the first in anything, and I don’t care if it’s the first woman, somebody of color, first LGBTQ, doesn’t matter. When you’re the first there’s just pressure and the pressure that I faced, and let’s just talk about the first, say, judges of color and women [there’s pressure] from two fields, okay, one area of pressure is from those who are very upset that the status quo is not being maintained. They really want things to not change. So this new type of person comes in, that breaks up the club. So their expectation, because it’s based on stereotypes, is that that person is going to fail. They’re expecting that person to just fail anyway. And they have these stereotypes. So that was one group that really kind of greeted me when I started. These were some of the good old boys who were on the bench when I arrived. And some prosecutors who had been there for a long time, liked things the way they were and saw me as somebody that might upset the applecart without even knowing me, right. So that’s one of the expectations. And then there were pressures from communities of color, who were saying, Please don’t fail, please don’t fail. Because if you mess up, then there won’t be anybody that looks like us for a long, long time. So there are pressures to not fail, there are pressures on the other hand of the expectation of failure. And I write about that in the book. And there’s one section if I could just read maybe four sentences. And it’s about when I was presiding in the criminal courts because that’s where I saw most people of color coming in as defendants. So I write this in the book: My tenure on the Criminal Court bench was a conflicted one. By simply donning my robe, I knew that I lent legitimacy to a system that disproportionately targeted people of color. My presence on the bench gave defendants of color hope that they would be seen not as a bunch of gangbangers, thugs, and drug addicts, but as human beings. And it would allow for the possibility that many, perhaps most, were better than the worst crimes they’d ever committed. One of my life’s sad recognitions is that it is far easier to understand the humanity of even the most egregious of offenders when that person resembles you. Less so when she does not.

Joshua Hoe

I was hoping that’s what you would get to. One of your first chapters, I’m really going to not talk about the specifics as much as overarching themes. But one of your first chapters is about the juvenile justice system. And you say that the notion, and I’m quoting here that “juvenile offenders are children in need of rehabilitation is fading fast”. You suggest that this is because of a combination of political and media narrative, and I think this doesn’t just apply to juvenile justice, which is why I’m pulling it out. Could you talk about politics and the media and how that worked, at least through your time as a judge?

Judge Cordell

The juvenile courts were established in the late 1890s, the first being in Chicago, and they were created because the idea was that juveniles should be treated differently from adults with respect to criminal behavior. And the idea is that juveniles should be treated in a way that they can be rehabilitated, that we don’t give up hope on our young people. And they’re immature, they’re not as developed and they shouldn’t be put in the same system as adults who are accused of committing crimes. And that system, the juvenile court system basically started to change and when we get to the 60s, 70s, and the 80s; punishment seems to be the main theme. And I think now, we’re seeing a shift back to looking more at rehabilitation and less incarceration of juveniles. And I’m glad about that. And I think it’s happening primarily because of the Black Lives Matter movement, and following the murder of George Floyd. So how do we go from starting a juvenile court that dealt with having hope in kids and rehabilitating them, to one that is for punishment, and a lot of it? I point the finger at the media, maybe taking a case where juveniles committed a terrible crime, it gets sensationalized. And then stories just start coming out where people start thinking, and again, this is how the media kind of feeds this, that juvenile crime is on the rise. And that certainly happened recently, there were statistics put out about, excuse me, not statistics, but stories put out about how juvenile crime had increased over the years, when in fact, it had not. And I write about this in the book. So the sensationalism of a particular case, really then gets the media attention. And then politicians take it and then enact laws that become very restrictive and punitive with regard to juveniles. That shift away now is happening, I’m grateful about it. And we need to really push hard to especially look at the incarceration of juveniles and try to change the direction. And that’s happening in California, where we are now the state has decided this; the juvenile prisons are now shut down, they were called the California Youth Authority. And now we’re looking at other ways of dealing with juveniles who are involved in the criminal legal system, such as rehabilitation. And it’s not to say that punishment is not a part of it. And I don’t want people to think that juveniles who commit egregious crimes are just getting, you know, big hugs. They need big hugs. But that’s not how the system is exclusively responding. So there it is punishment mixed with the idea that we believe in you, and you can be a part of our community. And you can do well. And that’s really now becoming a part of it, meaning bringing in other resources, social workers, drug treatment, it’s happening to juveniles, and it’s happening in the adult system as well. Slowly, slowly but surely.

Joshua Hoe

One really interesting thing that you raised was how much impact a judge, just by the way that they act on the bench, can have on a jury, according to the research you mentioned in the book, if the judge doesn’t, for instance, keep a poker face, they can literally push the jury towards one side or the other. Am I getting this right?

Judge Cordell

Absolutely. And I write in the book about judges’ verbal and nonverbal behavior and how it influenced jurors when I presided over jury trials, and I presided over lots of them. I’d look up occasionally. And I’d see jurors staring at me because they’re trying to read the judge because apparently, the judge, how the judge feels is important to them. The best example most recently I can give to you all is the trial of Kyle Rittenhouse. The judge who presided over that trial broke every rule in terms of not showing where you’re coming from and presiding over a case that it was clear from the judge’s words and from the judge’s looks, from even how he would lean over and be very close to Kyle Rittenhouse. At times, he showed his bias in favor of the defense, the lawyers representing Kyle Rittenhouse. And the optics alone if there’s one in particular where the judge is leaning over to the judges, right as if he’s looking at maybe a piece of evidence. And Kyle Rittenhouse is at the witness stand standing up leaning over so they’re touching shoulders. So it just looked, the judge looks so comfortable having this young man with him. And the jurors are seeing all of this stuff. So in my book, the chapter Bad Judges, if I had written this book a little later, I would have included that judge in the chapter.

Joshua Hoe

You also talk about the impact of legalese or the use of over-complicated language on juries. Can you talk about that a little bit more?

Judge Cordell

Oh, yes. So every time . . If anyone has ever presided on a jury when you go to deliberate, you get jury instructions. And before you go in, the judge sits there and reads from these instructions. And these instructions are standard. Every state has a set of standard instructions. The lawyers kind of haggle over which instructions the judge should read outside the presence of the jury. Then when they get the agreement, the judge reads the instructions. And I write about how those instructions have kind of changed over the years, that Supreme Court justices – and one of them was Sandra Day O’Connor – said that. She said sometimes these instructions are not even written in plain English, meaning the legalese. So what has happened is there’s been a movement and a change, to simplify the language in these jury instructions so that people can understand what the law is. Now, remember, jury instructions are just a statement of the law. So if you’re presiding over an armed robbery case, part of the instructions will define what an armed robbery is, and what the elements are, they have to be proved by the prosecution. And in some states, it baffled me, and I note this in a book, that the law does not permit the judges to give these written instructions to the jurors when they deliberate. So you listen, you’re hearing this judge go through all these jury instructions, sometimes they could take an hour to read them all. And then they can’t take the instructions in with them, to really understand them and keep them with them when they’re going through the facts and try to figure out what the evidence is. In California, jury instructions go in with the jurors. And it’s absolutely essential that they have them because that’s how they determine what the law is.

Joshua Hoe

I’ve talked about that there are, I think, intentionally parts of the book where you’re grappling with some tensions in your own process of writing this. And I noticed that multiple times in the book, you talked about how you love the law. And just earlier in this conversation, you made the comment about how it’s not a criminal justice system, it’s a criminal legal system. And then there’s at least four or five times during the book where you said you didn’t want to have to give a particular sentence but were forced by the law to do so. So what does it mean to you, when you say you love the law? And after all of this reflection, do you still love it in the same way you did when you took the first cases as a judge?

Judge Cordell

Joshua, I love your questions, even though this is the hardest one I’ve ever had to answer.

Joshua Hoe

It seems to me, that’s part of what you’re trying to work through in the book.

Judge Cordell

Absolutely correct, absolutely. Judges, when they take their oath, to uphold the laws, we can’t pick and choose what laws it is we want to enforce and uphold. And the dilemma I faced, as I write in the book, was that I was absolutely opposed to California’s Draconian three strikes law. Now, a three-strikes law is what’s called a mandatory minimum law, it means that the judge has no discretion whatsoever in deciding what sentence to hand down. So mandatory minimum laws paint all defendants with the same brush, it doesn’t matter about your upbringing, it doesn’t matter how rough your life had been. It doesn’t matter the good things you’ve done in your life, you just get painted, all with the same brush, and you get the same sentence. It’s almost as if you just have a computer at the bench, you just hit the buttons, and the sentence goes down. And as a result of these mandatory minimum sentences, most of them three strikes, which are – that type of law is utilized in many of the states – we end up with mass incarceration, which is disproportionate incarceration, especially of poor people and people of color. So when I, as I write in the book, I presided over lots of three strikes cases, and most of those cases involve defendants of color, black and brown folks, I agonized over imposing the sentences, meaning, I knew that by imposing the sentence, I was upholding the law, but I was upholding a law that I thought was discriminatory, was unfair, and just too harsh. And I don’t want your listeners to get the impression at all that this judge is just soft on crime. And, you know, let everybody out.

Joshua Hoe

I think if there was ever an audience that would be okay with that, it’s probably mine.

Judge Cordell

But at the same time, and I’ll tell you, if I were that kind of judge, I wouldn’t have lasted 20 years, I just wouldn’t have lasted, I would have been thrown out at some point. But my point is that even when there were laws that I didn’t care for, that I did not like that I had to enforce, I did not do so happily. And I would oftentimes make a record that basically helping this individual, this defendant, maybe on an appeal by saying I do not believe this is an appropriate sentence, but I’m compelled by the law to do it. So trying to figure out how there are ways that I could still maybe give that person a way of getting justice because in my view was injustice. And in fact, I write in the book, it’s about the third to the last chapter, about a man named Leo Hill, whom I sentenced to life in prison. I did not want to do it, for a lot of reasons. And people can read that in the book. And I, it was that case, it was after I imposed a sentence on Leo Hill, that I decided I couldn’t do this anymore, Josh and I decided I’m leaving the bench, I don’t want to be a part of this. And the last chapter in the book is called In My End Is My Beginning, I write that in a way, it’s about making amends, and about how I could somehow make a difference in a defendant’s life, even though I’m off the bench, to bring some justice. And I write about a case that I undertook after I left the bench and the two years it took for me to get some justice for someone who was serving life in prison.

Joshua Hoe

That’s a great answer. But I still think I have to ask the question when you say that you love the law, what does that mean? What does the love come from? I assume some of that is still there.

Judge Cordell

Sure. Of course. So the law for me is schizophrenic. If you look at the history of the law, the American legal system, it has been used to oppress people. So you have the Dred Scott decision that said, basically, you know, black folks, you are going to be enslaved no matter where you are; you have Plessy versus Ferguson that says, separate but equal, and it wasn’t equal, it was separate, and black folks didn’t get equal anything. And then you have, in 1954, you have Brown versus Board of Education, where you have a law that says, Nope, there will be no segregation in public education. And then you have other decisions that come along, Roe vs. Wade, I am a supporter of that decision. And so it’s this back and forth thing where we get oppressed, and I don’t mean just black folks, I mean, poor people, everyone . . .

Joshua Hoe

And the old case, Buck v. Bell, which allowed basically sterilizations.

Judge Cordell

Exactly. So you have these awful things perpetuated by the law. And then you have these wonderful things where people are freed, where rights are given, where you have the Gideon case, where you have a right to have an attorney appointed if you cannot afford one. So my issue is that we have, in this country, the best possible principles that support all of us, that the right to you know, pursuit of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness, the right to a jury trial, the right against self-incrimination. The problem I have, here’s the love/hate thing for me, is in the implementation of these wonderful principles, the implementation. So the principles, and the ones I’ve just mentioned, were actually promulgated by white men. And these were property white men, some of whom owned people who look like me, who put out these principles, but they did not intend that they apply to women, to poor people, or to people of color. So what we end up with is a system that starts out with these wonderful principles, and yet, it has so much of the “isms” baked into them, like sexism and racism, and homophobia. So I love the principles. I love what they stand for. And my issue is, we are not doing enough. And we must continue to work to see that these principles get implemented fairly and justly. And that’s one of the reasons I wrote this book. I love the law; at the same time, there are so many things that are broken, but that we can all fix. So it isn’t that everything’s all wrong. There’s a lot wrong. And that’s why in the chapter, The Fix, I recommend some things that I think can be done to bring some fairness and some equality in the implementation of these principles to this country.

Joshua Hoe

Well, just to keep on the same theme of making you answer difficult long questions, another theme that you return to several times in the book, is the tension between remaining accountable to the public and maintaining judicial independence. We’re entering what feels like a very dangerous period in this country where commitment to democratic norms seems in play, and all elected officials seem to be at risk in ways that might have seemed impossible even decades ago. How can we maintain judicial independence, but also a commitment to democratic accountability for the judicial branch of government?

Judge Cordell

Well, judicial independence is critical to maintaining our democracy. So why do I say that? We have three legs that support our democracy, executive, legislative, and judiciary. Right now, we’re at a time when our democracy is very fragile. I used to, all my life, take democracy, our democracy for granted. I don’t anymore, we’re in a very fragile place. If any one of those legs gets pulled out, we lose our democracy. And right now we are facing a real threat against the judiciary. So in the book, I write about a judge, a judge who was recalled here in California, Aaron Persky. And I write about him because he, first of all, was a judge on my court. I had retired from the bench by the time Aaron Persky was appointed to the bench. But I write about it because I was one of the spokespersons against his recall. So recall, by the way, there are no recalls of federal judges, none whatsoever. So they are appointed by the President and then they serve for life. But State Trial Court judges, State Appellate Court judges, and State Supreme Court judges are all subject to and can be subject to recalls. And basically, a recall is a campaign that says if you just get enough signatures on petitions, submit them, whatever the requirement is, and if they’re all valid signatures, then that judge can then be subject to a recall election, meaning the name goes on and the voters decide should this judge be recalled, and they don’t have to have a reason for recall at all. Now, in judge Aaron Persky’s case, he did nothing unlawful, not a thing. He exercised his discretion in sentencing a then-expelled Stanford freshman, 19 years old, to six months in jail, for after being convicted by a jury of sexually assaulting a young woman who was a grad, a college graduate, and both the Stanford swimmer and the young woman were highly intoxicated, I don’t want to get into the actual, what the facts were. What I want to do is focus, and I do in the book, on what Aaron Persky did. So he imposed a sentence that was entirely lawful but controversial. And as a result of that, some people got together and said, you know, we don’t like what that judge did, he should have sentenced that young man to prison. And what people of course, never talked about, who supported the recall of Aaron Persky, was that this young man was also ordered to register as a sex offender for the rest of his life. And think about it because murderers, after they have served their time in prison, and they’re out, they don’t have to register as anything, nothing, but this young man anyway has to register as a sex offender for the rest of his life. So my objection to the recall was its threat to judicial independence. There were other issues, meaning they portrayed the judge’s track record incorrectly, they lied about it. But the big issue was, he made a legitimate and valid decision, although controversial. So what is to be done, in my view, there, I don’t say abolish recalls, recalls do hold judges accountable. But I think they should only be utilized when a judge has engaged in malfeasance, when a judge has failed to perform the duties of the office or where a judge has been convicted of serious crime. And that is the way it is done in Georgia and in Montana recalls, and those two states can never be based on a judge’s lawful decision. If it’s discretionary, or if it’s even mandated by law, no matter how controversial. So I believe that recalls, and they’re not in every state, but they’re in a lot of states, of judges should be allowed, but only for those three specific reasons. California recalls are in the California Constitution. And I think that legislators should move to change the constitution with respect to judicial officers and limit recalls to those three reasons.

Joshua Hoe

Another fork on this judicial independence part of the book is the pressure that elections bring to this. I think there is a corrupting influence of fundraising, and also the pressure of organizations like the Association of Prosecuting Attorneys, and other groups and political action committees can bring to bear. But we also have this string of US Supreme Court cases that started with Buckley versus Valeo, that suggested that money is speech. And so people have a right to speak with their dollars. Is there much of a hope of challenging this kind of undue influence on elected judges?

Judge Cordell

So I want your listeners to know that everything that I write about in the book, including judicial elections, I have experienced, so I’m not just pulling stuff out of thin air. So judicial elections were first instituted in the late 1770s, in the early 1800s, when the then-territory of Vermont and the states of Georgia and Indiana used them to fill seats only on the lower courts. But then in 1832, Mississippi became the very first state to adopt judicial elections for all of its judges. So in the rest of the states at the time, governors appointed judges to lifetime terms during good behavior. Now, when I saw I was appointed to the bench by then-Governor Jerry Brown in the early 1980s, I wanted to move up to the next highest trial court, which is a Superior Court. I ran for election, there was an open seat. And there was someone else who wanted that seat. So the two of us ran for that seat. And this was 1988. I raised $70,000, primarily from donations from about 800 lawyers. And this is a pittance compared to today’s judicial races. Today, judicial races, particularly for state supreme court justices, will run easily, start at a million dollars. And so what is the funding of these? Where does the money come from? And as I write in the book, it comes from lobbyists, it comes from, and I’m just going to quote from the book, “During the 2015-16 Supreme Court election cycle, political action committees, social welfare organizations, and other non-party groups engaged in a record $27.8 million of outside spending, making up an unprecedented 40% of overall Supreme Court elections”. Okay, so there’s the money, how can it not influence judges, right? So how does it influence them, and that’s the bigger problem, the decision-making. And as I note, in the book, there was a look at judicial decision-making by the Brennan Center for Justice which is based in New York. And I’m looking at, they analyzed 15 years of television advertising data for State Supreme Court elections, to gauge the ads’ impact on judicial decision-making in criminal cases. And their findings are just astounding, and I note them in the book. But the bottom line is that during election years, judges tended to mete out harsher punishment. And in some instances, where juries decided that a person should get life, and not a death sentence, during election years, judges would then overrule that and say, no! Death sentences. You never hear complaints about judges who are throwing the book at people and giving out 100-year sentences and death sentences. But you always hear complaints about judges who are “quote/unquote” lenient, who are showing some mercy and some compassion. And so these judges, during election years, they decide, you know, if they just throw the book at people, they get re-elected. So in my view, Joshua, judges are not politicians, they just aren’t politicians who make promises to voters, to appeal to whatever it is their constituents want. And that’s fine. But unlike politicians, judges have to be independent, the only promise that they can ever make is to adhere to the rule of law, to legal principles, and to constitutional precedent, these cases that have come down, that’s what we adhere to. And so in my view, and I write this in the book, judicial elections should be abolished. I’ve been there and actually won, I won my seat, and I’m still saying they should be abolished. We need to replace them with independent nominating commissions that are bipartisan, that have diverse stakeholders on them, including non-lawyers, and their criteria for vetting these candidates should be transparent. The public should know exactly what is going on. And none of that happens in all the states. Now California has an independent nominating commission, but the Governor is not obliged to appoint those who come through that whole vetting process. And that needs to change.

Joshua Hoe

Returning to the theme of some tensions that we’re working through here, another part in this judicial independence part, in my mind at least, are the several parts of the book where you talk about problems with judging. For instance, in almost all the courts that you entered into, there was little to no training as you moved from appointment to appointment. And later, you suggested that there aren’t great mechanisms for accounting or accountability for sitting judges. There’s also the lack of mental health training, there’s all kinds of little parts. And if judges need to be independent, shouldn’t we also find ways to ensure that they know what they’re doing? Am I crazy here?

Judge Cordell

You are exactly right. So most people are shocked to find out that judges don’t get training. So judges come from lawyers, you have to have been a lawyer before you can become a judge. So let’s say, Joshua, you’re a lawyer, and you do contracts for 15 years. You do transactions, you love it, you’re good at it, but you decide at some point, I don’t want to do this anymore. I think I want to be a judge. So you decide to run for judgeship, or you apply to the governor and your state and the governor says, oh, you know, 15 years, you’ve got a good track record, people like you, and no complaints. You’re a judge. So you’re now on the court. And your first assignment is decided by the presiding judge. The presiding judge is just one of your peers who your fellow judges vote to be the presiding judge for a year or two. And that presiding judge makes the assignments and your first assignment could be family court, where you have to decide who gets the kids, or it could be mental health court where you have to decide whether or not somebody in a locked psychiatric unit can get out. And that person comes to you because they have a right to a trial. Or you have to decide . . .

Joshua Hoe

You gave a great example in your book that there was a mental health case, yet if your partner hadn’t been in the courtroom and known what the drugs were, you would not have known to question the person who was there.

Judge Cordell

Exactly. I would have blown it completely. So my first assignment when I was given a mental health assignment – and I’d been on the court for a while – I’m hearing a trial, and a woman comes in and she does not want electroshock therapy. Well, in some instances, actually, it can, some people do want it because it can be helpful in relieving depression. However, she opposed it, she had a right to have a hearing. Now, I’m sitting there hearing her treating psychiatrist saying she absolutely needs this. She’s got severe depression. We’ve tried all these other medications. I’m sitting there, what training do I have other than watching One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest with Jack Nicholson? None. So I’m thinking as I write in the book, wow, that sounds right. And, you know, then she testifies and says, I don’t want this, I’d rather look at some other medications, I get memory loss, I don’t want it. And what do you do when you have no training? So I write in the book, again, another teaser about what happened that day, when I’m presiding over this case. And you’re right, had my partner not been in the courtroom observing that day – she happened to be a clinical psychologist, and alerted me to what these medications actually were, that were prescribed by the psychiatrist – that I really understood what was really happening in the case. So I won’t give away what happened again. But I was able to do justice. But it’s scary when you think about it, the fact that there is no training. So let me give you one example. In California, there’s a California Judges College. And I taught at that judge’s college for about 12 years. And the course that I taught new judges was judicial ethics, and about bias. However, new judges come to the Judges College and they spend maybe 10 days just getting a sense about what it means to be a trial judge, and evidence and dealing with bias and getting a little flavor for basic things like the rules of evidence and those kinds of things. That’s it. So it’s just you learn on the job. And if you mess up, oh, well, you messed up somebody’s life. Let’s move on. Learn from it. That’s ridiculous. So I write in the book, one of the fixes is, first of all, there are no courses on judging taught in law schools, and lawyers are the ones that become judges. So we need to do something about that. And I write about that in The Fix. And the other is we need to – if you Joshua wanted to become a judge and you had gone to law school and you had practiced law for the requisite number of years, I still think you should try out, you should audition to be a judge and do what I did before I went on the bench, was to sit as a pro tem judge and have it individual’s on the nominating commissions observe you and anybody else who puts in an application to see how you handle yourself in court. What’s your demeanor like? I will say this book is from the perspective of a trial court judge. There are about 30,000 State Trial Court judges; we’re the first line, we’re the People’s Court, we’re the first ones you have contact with when anyone comes into the legal system. And in my view, you have to be a people person; if you don’t like people, you have no business being a trial court judge, none whatsoever. If you don’t like people, you’re going to be a terrible, terrible trial court judge. If you don’t like making decisions, you’re not going to be a good judge. If you want everyone’s approval, you’re not going to be a good trial court judge. So there are all kinds of things that need to be looked at. And they really aren’t. And we really need to focus again, because trial court judges have so much power over people’s lives.

Joshua Hoe

You also question the connection, the same kind of realm that we keep going down here, you also question the connection between judicial orders and people’s lived reality. You said, rarely if ever do judges contemplate how their orders will be carried out. Does the defendant have the wherewithal to pay that fine? Can the woman with an alcohol addiction afford the fee for the court-ordered counseling? Where will the evicted family end up? There’s no time to ponder these questions. That seems deeply problematic to me.

Judge Cordell

Yeah, yeah, it’s very problematic, which is why I wrote about it. And I write about what I took for granted. I’m sitting in family court, and I’m ordering – usually they were dads who did not have custody of their kids – and I’m saying, yes, you can have visitation with your kids. But because of your history of maybe you know, violence, these visits have to be supervised, and off they would go and then they come back into court weeks later. I didn’t have my visits; why not? Well, I don’t even know how to set up a supervised visit; what do I do? And that’s when it hit me, we’re just making these orders; it’s easy to do, sitting up on the bench on high wearing the black robe. And how are these people actually going to be able to meet these requirements that I’ve issued? So it really made me pull back and say, No, wait a minute. So what I did, I wrote in the book in family court, I figured out how to make these visits accessible mostly to dads who did not have custody of their kids where they could get these visits supervised. So part of judging is, and I write in the book about being a judicial activist, as being an activist for making the system the best it can be. And judges who just sit on a bench and go home after a day’s work and say they do good work on the bench is fine, but it’s not enough. Judges need to be activists in that sense, not in the pejorative sense of activism, like, I’m going to overturn precedent and do whatever I want, which, unfortunately, I think is happening with the US Supreme Court right now with a 6-3 majority on the conservative side, I see this, the negative side of judicial activism, I’m promoting the other, which is abide by precedent, but do everything you can to make that system better for everybody.

Joshua Hoe

You make reference, I think, throughout the book, to many places as a judge, where for lack of a better term, systemic and actual racism, sexism, and heterosexism were almost a casual part of your everyday reality. I think we’re at a place where states across the country are literally trying to legislate away the ability to even consider the existence of systemic bias. I’m really curious as to what your thoughts are about this, given your personal experience.

Judge Cordell

I’m appalled. I think we should all be very, very concerned, which is why voting is so important. If I were, if you were to ask me, Joshua, give me your one 60-second idea to change the world, or to change things in America, my answer would be voting, because it’s these legislators who are now enacting laws that are saying you can’t even mention the word race. So you can’t talk about anything that might upset somebody. I mean, where are we, what have we come to where now we’re looking at, you know, banning books, what’s going to happen next? So for example, California, the governor, Governor Newsom in 2020, signed a Racial Justice Act. And the purpose of that act is to weed out racism from the criminal legal system, meaning you trial judges in California, it’s your job to look, see if there’s racism and then do what you can to make it right, for example, peremptory challenges that I write about in the book, which are in jury selection. So if a prosecutor in a criminal trial says, Oh, I don’t want that juror, you’re excused Juror Number Two, you don’t have to give a reason. So there’s challenges for cause where the prospective juror says, oh, you know, I don’t like anybody who looks like this guy or wears facial hair and I can’t be fair. Okay, that’s for cause, get out, you can’t be a fair juror. But then there are peremptory challenges where a prosecutor or defense attorney can say, No, I just want to excuse the juror; I don’t have to give a reason unless the reason is based on, the person is dismissed because of race, or one of the “isms”, then it’s on the trial court judge when an objection is made, to say to the prosecutor, for example, why did you get rid of those two black folks on the jury? If the prosecutor gives a race-neutral answer, then it’s up to the trial judge to decide whether or not that’s credible. And historically, across the country, judges have just rubber-stamped whatever these quote-unquote, race-neutral excuses are. Well, the Racial Justice Act says you can’t do that anymore. You’ve got to dig deeper, and look into why these people are being kicked off the jury. And if it means holding a separate evidentiary hearing, then you do that. My concern is that states are passing laws that are saying, No, you can’t even deal with these “isms”. You can’t talk about homophobia, you can’t even – and I see it actually spilling right into the legal system [that] says you can’t enact laws like that, that might upset somebody. What? So that’s, that’s the problem. I’m very concerned.

Joshua Hoe

It’s terrible. Sometimes I wake up and I can’t even believe the things I’m reading these days. So we talked a lot about, you have a whole section on solutions. I don’t want to go through every single one of them. But many years ago, when this podcast started, one of the premises we started with is that one of the big problems we have is long and indeterminate sentences that a lot of people get. And I think you mentioned this several times in the book, too. I think way back in the day, Alexander Hamilton said, we have a tendency to weigh too much severity in how we enforce our laws. When you look at it as an overview, how can we best address this problem? When we talk about mass incarceration, to my mind, that’s the biggest problem we face. And you talked about several people several times in the book where you’re like this person, I had to give them 60 years, you know, maybe not 60 years, but 20 might have been more appropriate or 10 might have been more appropriate or something like that in the context of mandatory minimums.

Judge Cordell

Yeah, we are a punitive country. We are a punitive society when it comes to, especially [when it comes to] our legal system. And we basically send a message – when I say we, I’m talking about the prevailing attitude, particularly in our courts. If you look, most trial judges are former prosecutors. And in many instances, they’re just prosecutors in black robes when they get appointed. Which is why I’m hoping that at least in the federal system, that Biden appoints public defenders, people who have worked in areas where they’re not prosecuting people because there’s a certain mentality there. So we are, have become I guess, it’s been that way for a long time, a very punitive society. Which means we’ve just given up on people, and I believe that we are better than the worst things we’ve ever done. I believe that; now have I sentenced people to life in prison? Yes, I have. And I believe in the book I said I did it on eight occasions, none of them made me happy. None of them made me feel good. And in most instances of the eight, these were folks who really needed to be confined because they were just really problematic in terms of bringing harm to people in communities. But that being said, in imposing those sentences, they stay with me, I haven’t let them go. And again, I’m not a bleeding heart. But at the same time, I’ve lived long enough and see now a system that so disproportionately has imposed these harsh sentences on poor people of any color, and on people of color. So, if we look just at the criminal legal system, that’s where we’ve got to do better, which means we need trial court judges who need to be aware of their biases. I think trial court judges after a certain period of time – because you’re appointed or elected for a certain term and California six years – they should be audited. We should look at their discretionary decisions, when they set bail when they sentence and look and see how they give harsher sentences to poor people, people of color; are they setting higher bail for people of color, poor people? – and they should be evaluated. And that’s where you have these independent commissions that come in and look at these judges who want to go on and serve another term. Well, now you need to be looked at to see how it is you’re handling yourself. So we need judges who are from a variety of backgrounds. And we need trial judges, again – I’m talking about the states – who are not all primarily former prosecutors or in the big corporate world. I think we need, you know, we need that kind of diversity on our benches. So there’s much that needs to be done. And I don’t want people to feel overwhelmed and think it can’t happen, it can. As I write in the book, progress is measured not by how far we’ve come, but how far we have yet to go. And we’ve come quite a bit. I mean, as I told you, my great-grandmother was enslaved. And she would just, I don’t even know how she would handle seeing her great, great-grandchild sitting, you know, presiding in a black robe in a court. That being said, there is much we need to do. And I say to judges, you know, don’t just sit around, and not make things better. And I say to people in the community, there are things that we absolutely can do. And if not to be overwhelmed, focus on just the micro, right now focus on something in your community that you can change that will make this legal system a more fair and better system. And that means things such as – and again, I’m not saying something I haven’t done – running for office, I saw racial profiling by police in my community here in Palo Alto, California. And so I ran and got a seat on the Palo Alto City Council. And one of my first things was we needed an independent police auditor to look at the complaints about police in Palo Alto and then to make recommendations for change. So there are all kinds of things we can do, all kinds of them and I proposed some of them in the book.

Joshua Hoe

People have really liked, over the last couple of years, that I ask if there are any criminal justice-related books that you might recommend to others. So do you have any recommendations? If you don’t, that’s fine, too. But if you do, I’m sure people would like to check them out.

Judge Cordell

I wish I’d known this a little ahead of time because I read a lot of books. I know and I want to see mine up there, Joshua.

So I just finished reading a book by Shaka Senghor . . .

Joshua Hoe

Oh, he’s a friend of mine!

Judge Cordell

I interviewed him last week, it was for the Commonwealth Club of California. And unfortunately, we had to do it virtually. He’s in LA, I’m up in Northern California. But because of COVID we did it virtually. And he has written a second book – his first book was Writing my Wrongs – and then his second book, and this is what I talked to him about, was Letters to the Sons of Society. And it’s a book of 19 letters that he wrote to his two sons, one son he had before he went into prison, the second son he had when he came out. He did 19 years for a murder he committed when he was just past his teenage years. And he is amazing. His first book was a New York Times bestseller. So I recommend both of his books; his latest came out in January of this year.

Joshua Hoe

It’s a small world because Shaka actually is from Michigan, and he did his time in Michigan. We both got out of prison the same year.

Judge Cordell

Well, that’s amazing. So yes, I just spoke with him only a few days ago. And indeed it was a wonderful conversation. 1

Joshua Hoe

I always ask the same last question. What did I mess up? What question should I have asked but did not?

Judge Cordell

This was one of the most thorough and insightful conversations I’ve had about my book. I can’t thank you enough. And I can’t think of anything else that I wanted to talk about. I just want to make sure I leave you with this if I can. And it’s really my mantra. And I took it from Alice Walker, who wrote The Color Purple and she’s a poet and a social activist. So this is my mantra: activism is my rent for living on this planet. And I say to those who are listening in on your podcast, pay your rent. Okay, do something every day. I don’t care how small it is. To pay your rent for the right to just be living on this planet. So I, and I say it especially to our judges, activism, make it your rent for living on this planet. And my add Joshua, you are definitely paying your rent with this podcast.

Joshua Hoe

Thank you. I really appreciate you taking the time to do this, it was very nice of you. Is there a place you recommend that people find your book?

Judge Cordell

So the book is available at bookstores around the country. And if you’re on the West Coast, there’s Marcus Books, it’s the oldest independent black bookstore and it’s in Oakland, Marcus Books and they have my book. If people want to do the Amazon thing right now they can get it at half price. And it’s just at Barnes and Noble, you can just kind of, you know, go to my website as well, www.judgecordell.com. And you can find it just about everywhere. So I hope that people will read it and get a sense of what it’s like to be sitting on that bench and making these tough decisions from someone who tried to try to do the best I could, and is still trying to make this legal system, so I can call it a criminal “justice” system justice be in all parts of it, not just on the criminal side. So thank you so much, Joshua, for what you do to help make this legal system better.

Joshua Hoe

Thank you too. And thanks again for doing this.

Judge Cordell

All right, take care, my friend.

Joshua Hoe

And now my take.

It can be so easy to lose faith. Our laws are rarely well-written. And usually, the laws that are written are written in the worst possible ways. And those laws are also the laws that our society seems the most committed to holding on to, at all costs. Legislators way too often seem much more interested in investing in the politics of their office and the optics of what they support than they are about if they are passing good or bad policies. The press fans irrational fears and spotlights police and prosecutor messaging, often without even trying to present that messaging in context, or with the context of opposing viewpoints. We also have to compete with an entertainment media that largely mirrors this same problematic press narrative. Meanwhile, our friends and family members remain trapped in this nonsensical, brutal, counterproductive – and way too often – deadly system of prisons and jails. I know why people get frustrated. But our strength is that we have each other and that our numbers grow every single year. I know the tendency is to stay underground. But we have to work together. If we keep educating our friends and family members and speaking truth to power every time we have the chance, our sheer numbers will start to win the day. Eventually, we will be able to ensure that tough-on-crime legislators cannot be elected, that news outlets that continue to tell these questionable and out-of-context stories will go under, and the television and movies that feature these storylines will simply not be popular. They’ll be seen as ridiculous fiction. It’s hard to wait. And we have to keep trying to win the battles we can win every single day. But I have faith that we are on the winning side of this battle. As long as we continue to fight. I’m very proud to be in this fight with all of you.

As always, you can find the show notes and/or leave us a comment at DecarcerationNation.com.

If you want to support the podcast directly, you can do so at patreon.com/decarcerationnation; all proceeds will go to sponsoring our volunteers and supporting the podcast directly. For those of you who prefer to make a one-time donation, you can now go to our website and make your donation there. Thanks to our newest patron, Charles Fuller, and thanks to all of you who have joined us from Patreon or made a donation.

You can also support us in non-monetary ways by leaving a five-star review on iTunes or by liking us on Stitcher or Spotify. Please be sure to add us on Instagram, Facebook, and Twitter and share our posts across your network.

Special thanks to Andrew Stein who does the podcast editing and post-production for me; to Ann Espo, who’s helping out with transcript editing and graphics for our website and Twitter; and to Alex Mayo, who helps with our website.

Decarceration Nation is a podcast about radically re-imagining America’s criminal justice system. If you enjoy the podcast we hope you will subscribe and leave a rating or review on iTunes. We will try to answer all honest questions or comments that are left on this site. We hope fans will help support Decarceration Nation by supporting us from Patreon.