Joshua B. Hoe interviews Lance Kramer, Brandon Kramer, and Louis L. Reed about the documentary feature, “The First Step”

Full Episode

My Guests – Kramer, Kramer, and Reed

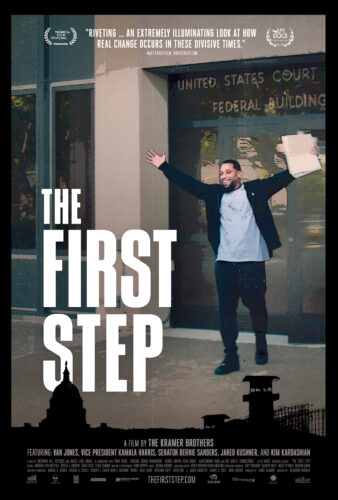

Brandon Kramer is an award-winning documentary filmmaker, educator, and co-founder of Meridian Hill pictures. Brandon’s brother Lance the co-director of the award-winning short documentaries Porchfest and Community Harvest. Together they created the Documentary feature “The First Step”

Louis L. Reed social justice reform advocate formerly with the Reform Alliance

Watch the Interview on YouTube

Watch Episode 138 of the Decarceration Nation Podcast on our YouTube channel.

Notes from Episode 138

Find screening dates and times for “The First Step” from all across the country

The Books that Lance and Brandon recommended were:

Klara and the Sun by Kazuo Ishiguro

The Water Dancer by Ta-Nehisi Coates

Full Transcript

Josh Hoe

Hello and welcome to Episode 138 of the Decarceration Nation podcast, a podcast about radically reimagining America’s criminal justice system.

I’m Josh Hoe, and among other things, I’m formerly incarcerated; a freelance writer; a criminal justice reform advocate; a policy analyst; and the author of the book Writing Your Own Best Story: Addiction and Living Hope.

Today’s episode is my interview with Brandon and Lance Kramer, the Producer and Director of the documentary feature The First Step; and Louis L. Reed, who was one of the main people featured in that documentary. Brandon Kramer is an award winning documentary filmmaker, educator and the co-founder of Meridian Hill pictures. Brandon’s brother Lance is the co-director of the award winning short documentaries Porchfest and Community Harvest. Together, they created the documentary feature The First Step, which is just starting its national release. In fact, in just a few weeks, I’ll be participating in a panel after the movie when it shows in Lansing, Michigan. Louis L. Reed is a social justice reform advocate who was formerly with the REFORM Alliance and was really central to the passage of the First Step Act. Welcome to the DecarcerationNation podcast, Lance, Brandon and Louis.

Lance Kramer

Thanks so much for having us. Thanks for having us. Really appreciate it.

Josh Hoe

I always ask the same first question. And since there’s three of you, there’ll probably be three very different answers, but feel free to just kind of pass amongst yourselves. How did you get from wherever you started in life, to becoming activists, film directors and producers, and working together to create a movie about the passage of the First Step Act? Anyone can start.

Louis Reed

So I think I’ll start. First and foremost, I am upset that this is my first time on this podcast with you, Josh, considering we’ve been in the trenches with one another over all of these years, we’ve shared space with one another. We’re relatively like family. And it’s the first time that I get invited into a podcast, but we can talk about that . . . We can talk about that on another episode. Look, I served 14 years in federal prison. And not only that, I served 14 years in federal prison, but I was predisposed to the criminal legal system at the approximate age of five years old. Well, both my parents were incarcerated and I had to be raised by my maternal grandmother. And so when you think about advocacy, for me, it actually began when my grandmother, who was an RN, at the time, used to have to go down to social services, in order to be able to get food stamps, because she would be taking care of both myself and my sister. And I saw how she had to advocate on her behalf, in order to be able to take care of two relatively small children. And so I think that my exposure to advocacy began as a result of my experience with my parents being incarcerated. And then ultimately, it was curated through my experience, being in federal prison for 14 years when I just saw too many people disproportionately impacted by our criminal justice system. And I wanted to do something about it.

Josh Hoe

Brandon or Lance?

Lance Kramer

I can say from my perspective, and maybe some of this will be shared from my brother’s since we did come from the same house. You know, we grew up in a suburb of Washington, DC, inside the beltway complex in Maryland. I did not know anyone who had been incarcerated growing up. It wasn’t something that was in front of my eyes, even though it was really, in a sense,very present right next door, many people’s reality in DC. But in our little enclave that wasn’t a part of our daily reality. I really wanted to be a filmmaker. And I think perhaps in part due to growing up inside the Beltway, I had this urge and drive in a sense to tell stories that I felt mattered. And that played a role in advocacy and activism. I think that that was strongly influenced from just growing up in the soup of DC. But I didn’t necessarily, at least at first, know that those stories would ultimately be so centrally focused on narratives around the criminal justice system, and particularly people who are directly impacted. There was a long journey that’s been about 15 years, almost 15 years of building relationships with people in DC in particular, and just finding that time and time and time again, the number of instances where you would encounter, we would encounter people who had had their lives turned completely upside down from the criminal justice system and the injustice of the system was almost inescapable, it was very central to the first film that we made, called City of Trees, which is more of a reentry story. And we just had this kind of progression, or I’d say specifically, [I] myself had a progression of feeling this, in a sense, almost [shame]. Because of that, there was the geography of where I grew up, the color of my skin, the class of our family, that we had been able to, in a sense, almost kind of escape the realities of these daily horrors that so many other people, in a lot of cases, where our peers had very similar personalities and backgrounds except for the circumstances that we’re born into. We’re facing these injustices, and it really made me confront what’s my responsibility to try and play some sort of role in changing that system as an artist, as a storyteller, as a filmmaker. And that’s kind of led to this. Now, you know, a multi-year journey, trying to understand these stories from a more personal point of view and bring them to light so that others can perhaps, you know, have some of the same insights that we’ve had. And I’ll say, on a really personal level, it wasn’t until we started working on the First Step film, that we also then wound up having people in our own family who had direct experiences with the criminal justice system. So eventually, it caught up with us, but not until we were actually working on the film itself.

Josh Hoe

Brandon, do you have anything you want to add?

Brandon Kramer

Yeah, there’s two things. One is that, you know, we grew up in a household and in a family and in a community where there were very deep interpersonal relationships, and connections. Some of that was with people that were politically and socially aligned, and some of which it wasn’t, it was with people, you know, cousins, uncles, aunts, that are on the opposite end of the political spectrum. But there was a very deep sense of connection, of vulnerability, of integrity, of respect, being honest, and truthful, confronting difficult kinds of conversations. That ethic and that set of values, I think, is something that Lance and I carry with us and has fueled our interest in storytelling around bridge building and around people forming relationships from very different backgrounds and lived experiences in both films that we’ve made. That’s one thing. The other thing I’ll just say is that just growing up in the DC area, as Lance mentioned, you’re surrounded by people who are trying to create a positive change in this world. And Lance and I have been really fascinated as storytellers in understanding what are the complexities around what it actually looks like to create change in this country? What are the emotions? What are the stakes that people experience? What does it look like from multiple vantage points? And so with City of Trees we followed the story, the human story, of when a policy, the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act passes. How does that impact a community in DC? And with this film, we were really interested in what is the human story behind creating policy. So following Louis, Van [Jones], and Jessica [Jessica Jackson, REFORM Alliance], in their advocacy efforts to actually create a bill that would impact 1000s of people’s lives.

Josh Hoe

So I want to ask a couple of film questions. I’m kind of a film buff, and, you know, I doubt I’ll get many opportunities to talk to producers and directors again. I think everyone has a dream at some point of being an actor or a director or producer, but it seems pretty impossible for most of us. How did that process happen for both of you all, and are the barriers as high as it seems they are?

Lance Kramer

The process or the origin of the dream, to be a filmmaker, goes back to when we were little kids. I mean, we used to borrow our parents’ old, clunky VHS camcorder and make not documentaries, and I certainly would not say that they had really any sort of social purpose. But they were just us playing basically with a video camera and bringing the neighborhood kids, our friends into the mix to make, you know, things that felt silly and fun to us. And that started 35 years ago. And the idea of wanting to be a filmmaker, both as a creative practice and also as a profession, I think, goes back that far, as well. I think that, for me, personally, though, that was interrupted by the reality that I didn’t know any filmmakers. Growing up in DC, it’s not like we were in LA or New York, where you could kind of spin in any direction and find someone who worked in film, that just wasn’t the reality, you know, here. So I didn’t actually know anyone that worked in film. And I certainly didn’t have any reference points for how you could do that as a career. So that actually felt very far afield. And I’ve had a kind of journey myself, at least professionally, and through education, of first studying journalism. And feeling like that was maybe the way to get close or proximate to storytelling, the kind of storytelling that I loved and film, but I felt like there was a little bit more of a career path in journalism, and it wasn’t film. That’s ultimately what I did after school. And then lo and behold, when the combination of the 2008 recession, and also just the kind of collapse of print journalism around that time started to really take hold, it forced me to really rethink what was possible, and a kind of long road that brought me towards moving back to DC. I was living on the West Coast, moved to DC, and just discovered this amazing documentary film community here that I never paid any attention to while I was growing up, but had been here, in fact, for a really long time. And there’s a great tradition of nonfiction filmmaking that actually comes from DC filmmakers, festivals, nonprofits. And I just started getting involved in the community here. And just found that documentary film in particular was this really amazing medium, and a community that was focused on excellent storytelling and excellent filmmaking, but also a very close relationship with activism and organizing and community-building and all these other qualities that are really important to me as a person, not just as a filmmaker. And so I just kind of dove in headfirst. And that’s pretty much what I’ve been trying to pursue ever since then, the past 15 years or so.

Josh Hoe

It kind of started for you all like the Fabelmans a little bit right? putting on plays with your friends and stuff like that. Brandon, did you have anything that you know, about overcoming the barriers and kind of starting that direction in your life?

Brandon Kramer

You know, I think I feel really blessed in having parents, like our dad is a sculptor and an architect. He has his own architecture firm. We have a lot of family members who have been entrepreneurial in their pursuit of whatever it is that they do in life. And in many ways, I almost felt naive to the barriers of creating your own business, your own pursuit of filmmaking, to me it felt like that is the path, my dad, that’s what my dad did, he raised us through his art form and creating a business around it. And so in many ways, the barriers have been a little shocking to me. It’s frustrating and disheartening at times – we could have a whole podcast on this – but you know, the documentary, we’re in a heyday, quote, unquote heyday of documentary film, more and more people are watching documentaries than ever before. And yet, there are so many independent documentary filmmakers that are creating very meaningful, complicated, bold films and stories that are struggling to make their way and permeate through some of these gatekeepers and platforms. And so I feel personally just very committed not just for our own film, but for our entire field in exploring and reconciling and trying to understand how this heyday that we’re in can be inclusive and embrace the incredible stories that are being created. Because I do think that there are some formulas and some ways that media is being created that do a really good job playing to the masses, but also can shut out films that are taking some bold and untraditional steps and frankly dealing with controversial figures and narratives like our film. This is not a safe film, what Van and Louis and Jessica did was not safe. They built allies with extraordinarily controversial figures and went into the lion’s den and took enormous risks to their, to their relationships. And I have deep, deep respect for them. And I think by telling a story about that effort, art mirrors life in certain ways. And, you know, in many ways, we were going up against the grain to some narrative trends that exist in our field.

Josh Hoe

I think it’s a good chance to bring Louis back in. I think a lot of people who are activists are interested in producing content, even if it’s just on social media or something like that. But I think a lot of people in our position as formerly incarcerated people are also afraid to do that. What things would you tell someone who’s just starting out?

Louis Reed

Well, first and foremost, you can’t talk about this film without talking about the State of Michigan, without talking about how Josh Hoe has been our secret sauce in being able to get the First Step Act really organized within the State of Michigan. I may share as well as Topeka K. Sam and David Safavian, and we may share the lion’s share of credit from the justice-impacted perspective. And we were much more front facing, but we don’t win this bill, we don’t we don’t win without Josh Hoe, really through the contacts and how you really just put your fingers in the dirt in the state. And I’m not saying that the state of Michigan is dirty. The work of advocacy, especially around the First Step Act, was really a messy process. And we didn’t win without Josh really being an integral part of our campaign. So I just really wanted to publicly give you your flowers, Josh, in that regard. Secondly, look, how do you get involved? How do you get started in advocacy? You do so based off of the issues that you’re passionate about, if you’re passionate about kids that skip in the rain, who seem to be in a some type of, you know, drought, then get passionate about it, get involved. You know, advocacy now, is different Josh, than when we probably first started. I remember when I initially went to prison, they had beepers, and I come home, now they have smartphones. And so advocacy can actually be literally at the convenience of your fingertips, you can see a cause that you want to be aligned to, you can simply retweet, you can post about it. You can start a podcast, you can go live, and just share what your notions are about a particular issue. But specifically on the First Step Act, what ended up happening is that you had the alignment of 1000s of people who had been impacted by the criminal justice system on the federal level, some even on a state level. And all of us came together and said, we want to do something. We don’t care who’s in the White House, so long as we can get our loved ones out of the prison house back to our own house. That’s, in effect, what the spirit of, what this film encapsulates, is the people who were trying to do our best to bring our loved ones home. That is it. And while we have the benefit of having cameras to document that process, this is a process that happens day in and day out, night in and night out on the local, state and federal level. You have people who have been impacted by an issue. Look, Jessica never spent a day in prison herself. But her heart was incarcerated when her ex-husband, the father of her firstborn child, was incarcerated in the state of Georgia, which ultimately springboarded her into a law career. The Kramer brothers, they have never been incarcerated themselves. However, when they heard about this bill that was being matriculated through Congress and trying to be ratified through Congress, I should say, they got more involved. They could have been doing a film on anything else. They could have been doing a film on police violence. They could have been doing a film on the rain forest, they could have been doing a film on a plethora of other issues, but they chose to put their camera and focus their lens on our issue. What is our issue Our issue is that there are too many black, brown and poor white people disproportionately impacted by the criminal legal system. Yes, we got people out. But we still got 70 million people in this country who have criminal histories. And so how do we reduce the 46,000 collateral consequences, according to the American Bar Association? How do we reduce those collateral consequences so that people can actually have full citizenship in their community after incarceration?

Josh Hoe

So some people are trying to just get some stuff out there. Maybe some people are actually interested in becoming, you know, directors, or producers or making documentary films, this will be kind of my last of the film-specific questions. But Brendan and Lance, I think Brandon talked about this a little bit already. There’s some struggles. I imagine money is one of the biggest challenges. How does the documentary film get made these days? What is the process? And what should people know?

Lance Kramer

Well, the way it gets made is, I guess it’s always been changing. But I feel like it’s changing very rapidly. Now, when we started making films about 15 years ago, we’ve always been independent filmmakers. And I feel like it was more the norm that you looked in one direction or the other. And we were surrounded by other independent filmmakers. And there were more independent paths that films traveled, film festivals, public broadcast, educational impact, that was the trajectory of a lot of films. And also this kind of scrappiness of running a Kickstarter campaign, call your mom or call your dad, call your uncle that you never call except, you know, when you need something, that was, you know, house parties, that was the way these things, favors, these things came together, not for everyone, but for a lot of people. And nowadays, you have multibillion-dollar streaming companies that are building huge parts of their portfolio, in their slate off of what they call documentaries, a lot of times they are really reality TV, or nonfiction, but different types of films than the kinds of things that we’ve been trying to make. But nonetheless, it’s become this huge, huge, huge industry. And so there’s that, which, you know, like Brandon was saying, in some ways, is kind of viewed as the golden age of documentary just because there’s more being made. But that is a pathway, at least from a career perspective, and to a certain extent, from a creative perspective for people to be a part of. But it’s also become much harder, in some respects, to make something independently, because that space has just consumed so much attention and resources. So in some ways, if you have an original idea, or a point of view or perspective that has been marginalized from that ecosystem, that commercial ecosystem in some ways, it’s actually become a little harder, in my view, to get things made. And also then seen. And you have to, unfortunately, bite very hard to get that thing made, and also to get it seen. And in a sense, your role as a filmmaker also starts to mirror the role of an activist or an organizer because you wind up having to do a lot of that type of advocacy for your own work, just for it to exist in the world. I think I get a lot of my lessons from Louis and team, you know, in terms of how they get a bill passed.

Josh Hoe

I think I just saw a picture earlier today, of you on a panel, maybe yesterday? I don’t know, talking about the film, maybe with someone from DreamCorps or dream.org.

Lance Kramer

Yeah, totally. We were on a panel with Candy and Milton, from dream.org last night, actually talking about this exact thing.

Brandon Kramer

And we are about to be on a panel with him again in four hours.

Josh Hoe

This is what happens when you’re starting a national release, right? So this brings us to the film The First Step. As we said before, Louis is one of the three stars of the film in a lot of ways. So Louis, do you want to describe the film for everyone?

Louis Reed

Well, look, I may be one of the three stars of the film. But my participation in the film, again, is a representation of the collective effort that went into advocacy on this film. You know, I can’t underscore to our listening audience enough, that you’re too modest, to brag on yourself, but I want to brag on you. We do not win The First Step, and we do not win Michigan, we do not generate the support out of the State of Michigan, without the advocacy, and without the genius and without the strategy of folks such as Josh Hoe, Elder Leslie Matthews, and also Nick Buckingham, as well. So I can’t underscore like, you guys really being the secret sauce in that particular state. But back to the above, in terms of what this film was about, look, this film is a microcosm, in effect, of a labor of love. The love that we have for this work, the love that we have for the people, and the love that we had, that had to rise above the hate that was tethered to the former administration, that was led by President Donald J. Trump; it literally was a labor of love. The reason why we refused to give up, the reason why we refused to die, you know, this, Josh, better than I do. The reason why we refused to die was because our love wouldn’t allow our, our people that we cared about to languish in federal prison under the provisions that we were trying to get accomplished on the federal level in the First Step Act. And so what you’re going to see is, what that process was like, how a conversation is translated into words on a piece of paper, as Brandon describes, that ultimately, is produced into a bill, that ultimately is taken up by a legislative body, that ultimately was passed. I will also add this as well, just as a PS, the First Step Act is literally unimpeachable. It is the only criminal justice reform bill, as far as I’m aware of, that has been passed by Congress, signed by the President of the United States of America, and as of June of 2022, has been affirmed by the United States Supreme Court. And to date, we have been able to release approximately 75,000 people as a result of this bill being passed. This bill has given birth to the Cares Act, and you know, other other bills that have been out there as well. So we’re extremely, extremely proud of the work that we’ve done on this bill. And again, you know, the viewing audience is going to see what our heart and soul was. And being able to bring this to fruition, the viewing audience is also going to not see a leftist apology film, or a film that specifically covers the right; this is literally something that is for every single person, no matter what side of the aisle you stand on.

Josh Hoe

And so we’ve got this movie, when you start the movie, it’s not you know, at the end of the journey. Brandon, how did you get hooked up with Van, Louis and Jessica, and get interested in this project and how did it move forward?

Louis Reed

Hey, Brandon, I think that you should probably tell the cool story that you captured in the film, that you always wish that you would have captured, about how, when you get to the portion about how [and] when I met Van. It’s pretty cool. Josh, we’ve never talked about this publicly.

Brandon Kramer

I’ll talk about how I met Van first, then I’ll talk about how I met Louis. Van, Lance and I knew each other I mean, I’ve known obviously, obviously I’ve known Lance my whole life. Lance and I met Van several years before we started production on this film. We had made a web series with Van called The Messy Truth, which was a series of conversations that Van had in the homes of Trump supporters to model how to have conversations across lines of division, and a few other projects. And in 2016, Van sat down with Lance and I and basically said, look, a lot of my peers [and] leaders in the progressive movement are going to be resisting and fighting this administration, and the harmful actions they’re going to be taking over these four years. That’s very important work. But I am going to be looking to find any room for engagement and common ground to get something done on the addiction crisis, on criminal justice reform, and any of these issues where there’s even a sliver of overlap. And as filmmakers that were deeply concerned about all the terrible things Donald Trump might accomplish, we were also even more concerned about the country spiraling away from each other. And we didn’t see that many stories that were being told, that really got into the nitty gritty understanding of what it takes to work across these lines of division. What does it look like? What does it feel like? Where is there room to accomplish something? And why are so few people doing it? And here we had access to a public figure and a leader that was running right into the lion’s den to tackle one of the most difficult issues: criminal justice reform, by means of working with Donald J. Trump and Jared Kushner, and other Republicans and Democrats. And we felt that whatever happened with that story, it would be a really important document for the American public to have, to experience, and to see. And we felt like the way that the story needed to be told was in a way that did not just empathize and connect and understand Louis’ and Van’s and Jessica’s point of view. But also the people, the progressive leaders like Patrice Cullors, like Bonnie Watson Coleman, who have been fighting for criminal justice reform their whole lives, doing really important work, but were opposed to the bill. Because that point of view needed to be respected and lifted up and empathized and connected with too. The film needed to represent fairly conservative leaders, Jared Kushner, Mike Lee, Rand Paul, who were working on this effort for their own reasons, which are very different, you know, whether it’s Christian conservative, reasons of redemption or, or wasteful government spending, or fiscal responsibility being the reason to work toward Criminal Justice Reform, they had their own reasons. And what we sought to do is create a film that gives you a window into multiple political positions on this issue. And audiences from a diverse range of backgrounds can watch it, they can find protagonists in the film that they relate to and connect with, and that align with their views. And therefore they can trust – hopefully – what they’re seeing, because we live in a moment where it’s really hard to trust anything, a lot of media just toes a certain line, and advocates for a specific position; this film doesn’t do that. But then they can also be introduced to a view that is different than theirs. And maybe not, the film is not seeking to convert anyone to a different viewpoint, but they can at least gain some understanding. And instead of how the media typically depicts these kinds of struggles and battles within parties or between parties, in a very reductive way, by engaging with it with a lot more nuance and complexity. The hope is that it disarms people, and then in their own lives, whether that’s with their neighbors, their families, school boards, or legislators working at the state level, they have some, a little bit, 2% more openness to building relationships and talking and dialoguing across these lines of difference. Louis I met . . .

Josh Hoe

I was just gonna ask you the story.

Brandon Kramer

It’s a long-winded way to get to Louis, sorry Louis. I was in the room when Louis was interviewing for his job with Van and Jessica and I actually had a camera in my hand. It was at a coffee shop. And, you know, Van basically said, Look, if you’re going to work with us, you have to be prepared to take enormous heat that’s going to come your way. We’re just at the beginning of this journey. And this is what we’re experiencing, we’re being attacked in this way. We’re being isolated, alienated. This is not for the faint of heart, and you really need to be in it for the right reasons, you need to be able to withstand a lot of alienation, isolation, because bridge-building in this moment is just not a popular path to go down. If you’re looking for laurels. If you’re looking out for your … if you’re looking to increase your followers, this is not necessarily the journey to go on. And I just remember, Louis, just you know, walking into that conversation. Louis, you’ll have to correct me because you know, I’m relying on memory here, but you had your own, my memory is that you had your own questions and concerns about what Van and team are happening, you obviously, were supportive enough to take the interview and have the conversation. But you also were a little skeptical before walking into that, if I remember. And I think in that conversation, you were you, Van and Jessica sort of laid out their strategy. And instead of seeing what was happening on social media, you were hearing it directly. And then what I saw was your strategy, your own strategy as an advocate and Van’s strategy as an advocate coming together and really merging in this beautiful way. And I’m sitting there as the filmmaker with my camera on my lap, not recording, because I felt like it was such a sacred moment. Like two people, two leaders were meeting each other for the first time. I didn’t want to – as a filmmaker, you have to constantly decide, you know, do I want to bring a camera into the space and 90% of the time, the answer is yes. Because you’re trying to make a movie. In this particular moment. I felt like it was so sacred, and so delicate, and I was just meeting Louis for the first time. I knew Van, but I didn’t know you. And I decided not to. And it’s something that I’ve had to wrestle with for the last six years. I’m like, oh, that would have definitely made it into the final cut of the film.

Louis Reed

You know, the interesting thing, Josh, is that I went to DC to meet Jessica, and with the expectation that I was going to meet Alex Gudich, who at the time was our Deputy Director. And it was supposed to have been a half an hour interview. And this half an hour, so-called interview ended up turning into an hour and a half, almost two-hour conversation. And it was just something that was like, I went in there with my own stereotypes and presuppositions. And I said, okay, at the very least take the meeting, you know, and just hear people out, because I wanted to be heard out as well. You know, based off of my experience, right, you know, aside from the social media portion, etc. I wanted to hear what exactly was in this bill, and how I could potentially, maybe with trepidation and apprehension be a thought partner. And literally in the process of that nearly two hour conversation, I was “eVangelized”, so to speak. And I just believed in Jessica’s strategy, I believed in Van’s leadership and ultimately, the fruits of it speaks for itself.

Josh Hoe

We were giving each other flowers and you were giving me flowers earlier, I want to give you back your flowers. You in a lot of ways were the face of this thing. All across the country and meetings, and in rooms full of people in every state, you know, probably in the whole country. And one of the most powerful I think, maybe the most powerful scene in the movie, at least for me, is where a legislator, in essence, tries to deny you your dignity and your ability to change. And you kind of read him. And it’s really kind of the core of what we work on, I think, as activists in this area.

Louis Reed

Just not only what we work on, but what we work through. That’s a reflection of what we have to go through every single day. Not while we are walking the halls of power. But literally while you’re walking your own block in your community. You have police officers who want to reduce your personhood down to you having a criminal conviction. You have probation officers who only see static factors in your life rather than those dynamic things that you are evolving into and out of. You have social service people who won’t even speak with you with a degree of empathy [or] human dignity, because they’re looking at a background and they’re saying, Oh, you’re ineligible for this based off of this right here. So while the film captured that exchange, between me and that individual, that really represents the things that you and I are faced with every single day as a result of being justice-impacted.

Josh Hoe

So having gone through that, what was it like to see that on screen? Was that different than. . .

Louis Reed

Yeah, I’m gonna tell you, in the moment, I was focused on a mission. It was mission, mission, mission, mission, mission, mission, mission. The first time that I saw that, I got emotional. I didn’t realize the gravity of what that exchange was like, for me. And for other people who actually watched it. We’ve been in screenings where people, you can audibly hear people in their seats, gasping, like, oh, the nerve of this guy, right? And then you can hear the applause at the end of that exchange, right. And most times when I get feedback about this film, folks always point to that particular scene, not just because I’m in it; it is just kind of like wait, how are you holding up, you almost watch it and forget that it happened years ago, right? Because people come up to me like, Hey, how are you feeling? And I’m like, I’m great. But yeah, I just saw that scene. It didn’t happen in the hallway. This happened, and it was recorded. It was filmed, and it was edited. However, I’m okay. But I think that’s how visceral a reaction that people have. And that’s how invested they are in the film up to that point, where it’s kind of like, wait, what I’m here, I’m with these people. Right? Like, I know, Jessica, I understand Van. I’m with Louis, I’m with all of these people, and for you to do that to him. No, I don’t like it. So I think that’s what that particular scene embodies.

Brandon Kramer

I just want to underscore something you said, [that at the end] of that scene, in many screenings, you get full applause from the audience. I just want to be clear. In documentary film screenings, you do not get applause. Maybe if you’re lucky, at the end of the film, when the movie ends. For it to be in the middle of the film, and have in many cases, people screaming at the screen and applauding, it’s an incredible, it’s not an incredible feat of filmmaking. It’s an incredible feat of Louis withstanding a level of denial of his humanity and just pushing right through that. And that registering with audiences the same way they respond to moments in superhero movies, you know, it was like Batman in a way or I don’t know, it’s a superhero moment.

Josh Hoe

A funny aside is that Louis and myself and Lance were at a screening of this at the Detroit Film Festival. And it was during COVID. And so there were like, 13 people in the room, and there was still that reaction, even with only a few people in the room. So you know, it’s pretty powerful. Hopefully, everyone will get a chance to see that, and understand what we’re talking about. Lance, so, you know, there’s this process and you’re watching legislation. Did you all have strategies mapped out? Like for if it had been delayed another year or changed? Or what if it hadn’t passed? I mean, what would have that done to the documentary process?

Louis Reed

I want to talk about what that would have done to the legislative process. If we didn’t get it passed. You remember, Josh, everyone, everyone was saying, Now is not the time. Let’s wait, let’s wait until we get a new Congress. Let’s wait until we get a new President. We can’t give this President a win. We can’t give Lindsey Graham and the Republicans in the Senate a win. We can’t give them a win. If we would have waited, or if that bill would have died, there would have been no resurrection of the First Step Act. Let’s be clear. So before we talk about the documentary process, let’s ultimately talk about the legislative process because what this film does, it captures what the legislative process was, right? And so yes, Lance can speak to this, you know, of a better mind than I can from the filmmaking perspective. Yes, a film may have been made, that’s without question. But would the film have been made with the impact that we were able to have as a result of this bill being passed, I highly doubt it.

Josh Hoe

And Louis, I don’t know if you remember, at the Detroit Film Festival, the moderator asked me, was it all worth it? Yeah, I just started to laugh. And at that time, 30,000 people had come home. That’s why I do this work. Of course, it was worth it. So yeah, for those people’s lives, it was really important that we passed it. And you know, there are probably 10 times I can remember where it felt like it was dead in the water. And just we just kept on fighting.

Louis Reed

I toss it over to Lance. But Brandon and I, the other night, at the New York premiere, for the first time, we talked about how there’s a moment in the film, where I heard for the first time from Brandon, him saying that he just thought that it was over. It was done. Like, let’s, let’s pull the plug on the cameras. And let’s get started thinking about what the final scenes are going to be because it was done. And we thought that at the time, Tom Cotton had outmaneuvered us. You know, this bill died, at least, at least 10 times. It, you know, and it was resurrected at least 30 times. So, yeah, but, but go ahead Lance.

Lance Kramer

No, I mean, I’m glad you spoke up first, because in a sense, it’s like the film, [in] a documentary film, you’re trying to capture reality. You’re trying to capture something in real life that’s happening before your eyes. So we didn’t have a script. We were trying to be responsive to what was happening in real time. If you go back to when we started the film, we knew Van, but we didn’t know Louis, we didn’t know Jessica, there was not a bill, Van didn’t know Jared Kushner. So all these things when we started back in, you know, late 2016, early 2017, though, we had a question. And we had a curiosity about what to try and capture in the story. But we didn’t have all the specifics. And so this whole time, we were trying to just follow, we were trying to follow the story as it was unfolding. And so you know, we didn’t know what would come next. We knew how hard everyone was fighting for it. So we knew they weren’t going to let up till the bitter end. That was clear, clear as day. But I will say that there were moments, especially during that time where the outcome of the bill was uncertain. And even when the bill was basically dead, because it almost, I think, for all intents and purposes, for the people fighting for it felt like, you know, it wasn’t just on the ropes. But it might have just been, frankly, just like totally dead in the water at certain key points, some of which is in the film. You know, I was having conversations with mentors, just from a storytelling perspective that I was trying to understand, okay, so if the bill doesn’t pass, you know, what kind of story do we have here? And, you know, people are saying, well, you know, you got to remember, I remember very vividly that I had a conversation with one of my mentors who said, you know, maybe what you’ll have here is a Rocky story. People forget that in Rocky . . .

Josh Hoe

Rocky doesn’t win, he loses.

Lance Kramer

Everyone loves Rocky, it’s one of the great films of all time. He loses in the first film. And so I remember, one of my mentors said to me, he’s like, Well, you know, you might just wind up having a Rocky film, which is a great film. But then, that kind of stuck with me and I was trying to just, you know, we couldn’t and would never want to force the narrative one way or another. We were trying to understand what will be revealed or offered to a viewer from having had the experience of being with everyone through this journey and through this fight, so that there’s something impactful to take away one way or another. you know, and think you know, thank God the bill passed and and all these circumstances coalesced so that signature could become a reality.

Josh Hoe

So you all have been rolling out the film for a while now, there was the circuit of all the festivals and now you’re starting to do a national release. For anyone watching or listening to this now, what’s something you would like to tell them about either why they should go see the film or why it was so important to each of you? I think all three of you can take a stab at it.

Lance Kramer

So I’ll say that obviously, you know, we’ve all lived through COVID the last couple years, three years, going on three years now, you know, and the level of isolation, I think has hit everyone in deep and I know very different ways for everyone. I think you probably could not find any person, there are very few people in this country that haven’t done a lot of watching movies at home, by yourself or just with your family, you know, streaming a film. And it’s great to see, great to know that films are as accessible as they are right now in that respect, but for some films, it really makes a difference to go into a movie theater, on a big screen with no distractions. Sit with people who you either know or you have never met, be immersed in a story, hear those gasps, like what Louis and Brandon were talking about, feel, if there’s a moment of a film that’s uncomfortable, to feel that with other people, if there’s a moment of victory, to feel that with other people, just be immersed, I think is something that has always been very precious and special and important, and I think especially nowadays is really critical. And then on top of that, to be able to have the experience of hearing from people like Louis, like Candy and Milton, like Britton Smith, like the countless local leaders who are showing up at every single one of these screenings. [I] repeat that there is not a way to see this movie in the United States where it is not presented with organizations and leaders who are working on the frontlines of trying to pass criminal justice reform or bring people together on a local or national level. 100% of the screenings are programmed that way. And so this is also a really, I think, impactful and important opportunity to not just experience the film, but also meet these frontline leaders and organizations and learn how you can be a part of that work. And so we tried to be very intentional in designing the release, to put that at the forefront. A lot of these organizations too are led by justice-impacted people in states where it’s not easy to get things done, and they need all the help that they can get. So that would be my pitch. It’s a really unique and I think important, not just experience, but frankly a movement that people can be a part of, just by showing up and going to the screening.

Josh Hoe

Brandon, do you have any thoughts?

Brandon Kramer

Yeah, I’ll say a few things. One is that there is a bill that was just introduced this week called the Equal Act. I don’t believe we’ve talked about that yet on this, have we?

Josh Hoe

[It was] reintroduced actually, it almost, could have, should have probably passed last session, but hopefully it will this time.

Brandon Kramer

[It] reintroduced Lindsey Graham as one of the sponsors of the piece of the legislation. This bill would impact another 10s of 1000s of people’s lives, it is very much a continuation of the advocacy that you see in this film. So for one, just learn about the bill, go to dream.org, go to the Reform Alliance, do your homework to find organizations working to push this bill forward, because it is a major way to impact people’s lives who are impacted by the system. That’s one thing on the criminal justice side. On just the human side, I had somebody at a screening recently say to me, you know now that January 6 happened and now that all the terrible things that Donald Trump and the Republican Party have done since that time, do you have regrets about telling the story? Or would you have done it differently? And I’ve gotten this sort of question at different moments through almost 100 screenings that we’ve done. And the answer to that is no, the answer is to me, I hope one of the major takeaways of this film is that you get to see, you get to sit in the safety and comfort of a seat in a theater and experience in a very intimate way, what it felt like for Louis to have the kind of exchange that you were discussing with Lawrence [Leasing], to see Tylo James, an activist from South Central Los Angeles, go on a plane and go to West Virginia to meet with Trump supporters and sit at a diner across from them and break bread with people whose votes have been extremely damaging and consequential to her and her community. These actions take enormous courage. And they’re very unpopular, and they’re very controversial. And my hope is that you get to sit in a theater and it makes you a little uncomfortable. And you have to wrestle with that, we had to wrestle with it as filmmakers, and God knows, Louis had to wrestle with it when he stepped foot in these spaces. And maybe it flexes some muscles in your gut, that can increase your tolerance for stepping into difficult conversations or uncomfortable spaces. Because if we don’t do that, then we’re going to continue down the path we’re going down, which is not serving us very well. So I hope the film can be just a small bit of medicine, to breaking down some of these hardened ways that we are, and they were hardened for good reason, because there’s terrible things happening. And it’s hard to even remotely consider building a relationship with people that are causing enormous harm and damage to your community. But we have to find some way to get at each other’s hearts and minds. Otherwise, we’re going to continue down the path we’re on.

Josh Hoe

What’s next for you two? Now that you’ve finished this project, once this finally, you know, once it’s had its national run, and all that, what’s what’s on the horizon for you two?

Lance Kramer

Well, we want to, it’s interesting, we’ve done a lot of reflection, just about the kinds of stories that we’ve told over the last decade and a half, which have all been nonfiction, one of which has been very personal, but most of which have not been directly about us or our family, so to speak. And, you know, going back to when we were little kids I was talking about earlier, and we were, you know, dreaming about being filmmakers. To be honest, we weren’t dreaming about being documentary filmmakers, we were visioning more being fiction filmmakers. And so I think that our experience, as documentary filmmakers, has taught us how to make films. I think just storytelling kind of doesn’t necessarily fit into like nonfiction fiction boxes, it’s just hopefully good storytelling. But we’ve had, we’ve done a lot of reflection and kind of gotten in touch with a lot of narratives that we really would like to tell that are fictional, that would require writing them, but are very personal or just close to our own experience in some shape or form. And that’s been something we just both creatively and personally, personally wanted to explore with our next project. So I think probably the next film that we produce and direct together will be a fiction film. And then we also want to use some of the things we’ve learned from making nonfiction films of our own and also just the relationships and connections and whatnot that we’ve built to try and help some other people get their films made and seen. And so that’s also something that we’re trying to focus on as well.

Josh Hoe

Okay, I always ask my guests if there are any criminal justice related books that they like and might recommend to our listeners. Do either or both of you have any favorite books that might fit into this? As you look behind me, if you’re watching instead of listening, you can see I’m a big reader.

Brandon Kramer

Yes, I recently finished reading the book Klara and the Sun. It’s an incredible film that takes the point of view of an artificially intelligent doll for a little girl. And you know, people often talk about AI. They think sci-fi, you think thriller, you think, you know, end of the world devastation. This is a movie that looks through the lens of an artificially created being. And through her as the protagonist. It reveals just so much about the complexity around you, a family’s fear of death, and fear of losing each other, and the pursuit of technology to cover up and try to avoid direct confrontation with a real sense of loss and tragedy and family. And it’s a beautiful, beautiful film and a beautiful book. It plays like a film in my head, and I highly recommend it to anybody.

Josh Hoe

Well, coming from a filmmaker, that’s high praise, right?

Lance Kramer

I’ll recommend, I recently read The Water Dancer by Ta-Nehisi Coates, his novel. And I bring it up in the context of this conversation, because this is a novel written from the perspective of someone who was enslaved. And in an incredibly gripping and heartbreaking and powerful, very personal way. And it, it shed light on the point of view and perspective of someone who had been enslaved in ways that I had never just never grappled with, on the level that I did through reading that story is, and so I think, also, it’s just informed not just my sense of history from that time, but also, obviously, as you know, the origins of the mass incarceration system go way back to that time, too. So it’s helped me to just gain some greater perspective on a lot of the issues at hand today. And, it’s also just a beautifully, beautifully, beautifully written book, highly, highly recommended.

Josh Hoe

So I always ask the same last question, what did I mess up? What questions should I have asked, but did not? I always consider this kind of the humility question, but I just like to hear what people would have liked to talk about, if there were things that you would have liked to talk about.

Lance Kramer

I don’t think you messed up at all, Josh, I think the only thing I’d say is, maybe I’ll kind of build off Louis, it’s like, you know, I think you’re almost too humble. Because you do so much incredible work yourself. And, you know, as curious as you’ve been to hear from us, in the conversations that we’ve had, you know, outside of this podcast, I’ve learned so much from you. And so there’s a part of me that wishes that there was maybe more equity in the interviewer/interviewee dynamic, because yeah, that’s my biggest gripe.

Josh Hoe

I have done a couple episodes where someone interviewed me, where I just let them kind of go crazy. But you know, I mean, when you’re the host, I don’t know, I always look at it as the host is hopefully making the guests the center of the things. So I don’t know, it’s just my personal approach.

Lance Kramer

Also, I just love your take on film. And the conversations that we’ve had about movies, not just in the world of criminal justice, but just movies and, and your love of film is something that I love about you. And I just love talking about movies and stuff we love. So that’s also maybe just, in another episode or just in Lansing, we could talk more about it.

Josh Hoe

If it wasn’t a criminal justice podcast, I would definitely do whole episodes just about movies, because I see pretty much every movie that you can see, as long as I can find it in Lansing. Brandon, is there anything you wanted to talk about that maybe I didn’t hit on?

Brandon Kramer

No, just look, if your viewer, your viewers or listeners want to watch the film, firststepfilm.com is the place to go to find out if the film is playing in a city near you. Follow the film, First Step movie on all the social media platforms. This is an independent film with an independent release. It’s not a big major studio film. It feels like a big major studio film when you see it. But it’s not. We’re relying on the support of a grassroots groundswell to get this film into the world. And so anyone who has been moved by the words that you’ve heard on this podcast, please follow us to find out if this is playing near you. It will be released, streaming sometime in the coming months. And so you can, by following us on social media, you can also find the film, if it’s not playing in a theater near you, when it will be playing online, and then you’ll be able to watch the film in that way. Really appreciate being on your show, Josh.

Josh Hoe

And for those people who are listening in Michigan, it’s going to be shown in Grand Rapids, I think on the 7th. Is that right? Maybe, and then I think, in Lansing on the 9th, and I’ll actually be there for that. So anyone who wants to say hi, that’s a good place to catch me. And, yeah, just thank both y’all for doing this. This was really, really great. And it’s nice to finally meet you, Brandon.

Brandon Kramer

It’s great to meet you, too. Lance has said wonderful things about you. Louis has said wonderful things about you. I’m honored to finally meet you and to be on your show. And thanks for just the thoughtful questions.

Josh Hoe

My pleasure. Okay, thanks a lot.

Josh Hoe

And now, my take.

Lance mentioned the Equal Act during the interview. And I should mention that this is federal legislation that will finally finish one of the most important parts of the First Step Act, and the legislative activity that many criminal justice reform folks have been working on at the federal level for a lot of years now. In 2010, the Congress changed the charging ratio of crack cocaine from 100:1 compared to regular cocaine, to 18:1, but that legislation, called the Fair Sentencing Act, didn’t make it retroactive. With the First Step Act, we made the change retroactive. And now with the Equal Act, we could finally change the ratio of crack cocaine to regular cocaine, to chemically identical substances, to 1:1 and finally, end for everyone one of the most racist and disparately applied laws in the recent history of our country. Unfortunately, we’re in the midst of a new tough on crime frenzy. And the 2024 candidates, including President Joe Biden, are signaling that they want to go back to the 1990s, which is when a lot of this nonsense started, although the crack versus cocaine started before that. And we are going to have to do everything we can to make sure that we tell them this is not acceptable. And at the very least, we need to make sure that the Equal Act finally gets signed into law. We did it once, it’s time to do it again. Get involved, call your representatives and senators and call the President. Let them know that if they want your support going forward that we will expect them to support reform and support the Equal Act. I hope everyone gets a chance to see The First Step. It’s a wonderful documentary, and well worth your time.

As always, you can find the show notes or leave us a comment at decarcerationnation.com. If you want to support the podcast directly, you can do so from patreon.com/decarceration nation. For those of you who prefer to make a one-time donation, you can now go to our website and make a one-time donation. Thanks to all of you who have joined us from Patreon or have given a donation. You can also support us in non-monetary ways by leaving a five-star review from iTunes or add us on Stitcher, Spotify or from your favorite podcast app. Make sure and add us on social media and share our posts across your networks. Thanks so much for listening to the DecarcerationNation podcast. See you next time.

Decarceration Nation is a podcast about radically re-imagining America’s criminal justice system. If you enjoy the podcast we hope you will subscribe and leave a rating or review on iTunes. We will try to answer all honest questions or comments that are left on this site. We hope fans will help support Decarceration Nation by supporting us on Patreon.