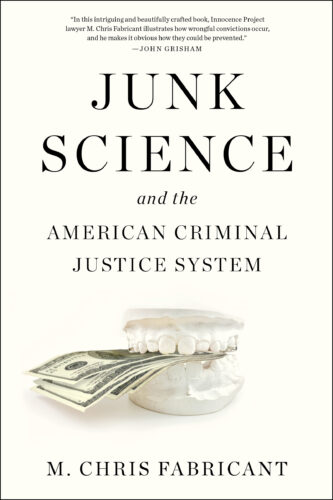

Joshua B. Hoe interviews M. Chris Fabricant about his book “Junk Science and the American Criminal Justice System.”

Full Episode

My Guest – M. Chris Fabricant

M. Chris Fabricant is the Innocence Project’s Director of Strategic Litigation and one of the nations leading experts on forensic sciences and the criminal justice system. A former public defender and clinical law professor. Fabricant has over two decades of experience ranging from litigating death penalty cases in the deep south to misdemeanors in the south Bronx.

Watch the Interview on YouTube

You can watch Episode 127 of the Decarceration Nation Podcast on our YouTube channel.

Notes From Episode 127 M. Chris Fabricant – Junk Science

The books M. Chris Fabricant recommended were:

Bryan Stevenson, Just Mercy: A Story of Justice and Redemption

Tayari Jones, An American Marriage: A Novel.

Full Transcript

Joshua B. Hoe

I’m Josh Hoe, and among other things, I’m formerly incarcerated; a freelance writer; a criminal justice reform advocate; a policy analyst; and the author of the book Writing Your Own Best Story: Addiction and Living Hope.

Today’s episode is my interview with Chris Fabricant about his book, Junk Science and the American Criminal Justice System. Chris Fabricant is the Innocence Project’s Director of Strategic Litigation and one of the nation’s leading experts on forensic sciences and the criminal justice system. A former public defender and clinical law professor, Fabricant has over two decades of experience ranging from litigating death penalty cases in the deep south to misdemeanors in the South Bronx. Welcome to the Decarceration Nation podcast, Mr. Fabricant, it’s a real pleasure to have you on.

M. Chris Fabricant

A pleasure to be here. Thanks for inviting me.

Joshua B. Hoe

I always ask the same first question, how did you get from wherever you started in life to where you were the Director of Strategic Litigation at the Innocence Project?

M. Chris Fabricant

I think that you can really trace it all back to a drug bust in 1969 when my mother was indicted for trafficking in hash, and my father [who] was a public defender in 1969, was assigned to her case. And the product of that union was me, a very short-lived marriage, but ultimately, you know, I think you can draw a straight line from that to my work around the advocacy of reforming the criminal legal system. And it’s really been something that’s been ingrained in me since as long as I can remember, and I always knew that I was going to be a public defender. And I was a public defender for many, many years, and like most people who have worked in the legal system in this country, after a while representing individuals and experiencing second hand, but at least observing firsthand the devastating impact of our carceral system in this country, that you want to try to do more systemic work to try to create broader change. And that’s really what led me ultimately to the Innocence Project after spending a long time as a public defender.

Joshua B. Hoe

I tend to work on the other side of the pool, trying to help folks who probably were guilty, at least of something. Could you talk a little bit about the Innocence Project for folks who might not be familiar with your work? I know most people probably are, but probably worth at least mentioning.

M. Chris Fabricant

The Innocence Project really has two missions, and one is to free the incalculable number of people who have been wrongfully convicted in this country. And if you think about how many people we have in various forms of incarceration in this country, 2.3 million at any given time, we think maybe, even if only 1% of them have been wrongfully convicted, we’re talking about 10s of 1000s of people. And the other aspect of our work is to prevent future wrongful convictions. And so we work in both DNA – and more recently in this being our 30th anniversary – have begun to do a little bit more non-DNA exoneration work, and I write about a couple of early cases at work and in my book. My role at the Innocence Project in particular is, as Director of Strategic Litigation, what we do, and the attorneys in my department do, is litigate around the leading contributing factors of wrongful conviction. So you know, the number one – as far as DNA exonerations go – is eyewitness misidentification. And the second leading contributing factor is misapplication of Forensic Sciences. Nearly half of all wrongful convictions are attributable, at least in part, to the use of unreliable forensic evidence.

Joshua B. Hoe

Before we get to that, something you just said interested me. I think most people aren’t aware of the problems with unreliable testimony. We tend to think that if someone says that they saw something, that that must be the case, but that has become pretty problematic, at least from a research perspective, am I wrong?

M. Chris Fabricant

No, you’re absolutely right. We have a lawyer in strategic litigation, Tom Robinson, that’s all he does is litigation around the use of eyewitness identification at trial, because we know today, this is similar to forensics, that there are really cost-effective ways to ensure that lineup identification and other forms of eyewitness identification evidence is done in a way that is not suggestive, and that are actual tests of witness’s memory rather than a test of the police or investigators theory as to who was the actual perpetrator, blinded lineup administration and avoiding the use of show-ups and a whole host of other reform efforts that go into trying to prevent eyewitness identifications, which have been shown again and again and again to be inherently unreliable, and especially so if they’re done under suggestive circumstances.

Joshua B. Hoe

These interviews tend to, we talk about pretty serious subjects, and they tend to get a little heavy. So this season, I’ve tried to lighten it up a little bit at the beginning, and ask people if they have any hobbies that people might not know about, just to get a little bit of a better feeling about the folks that I’m interviewing, as opposed to just the dark and depressing end of criminal justice work.

M. Chris Fabricant

My hobby is really writing.

Joshua B. Hoe

The love worked out well, for the book, I suppose.

M. Chris Fabricant

I’ve got two kids. And we have a very busy life here in Brooklyn. So that plus writing plus working at the Innocence Project really takes up almost all my time. Also a runner, I guess, you can throw that in, but absent that, you know, I don’t really have time for other hobbies. I read a lot. You know, I don’t know, I guess a little bit of this and that, but primarily I write, I litigate, I go to bed.

Joshua B. Hoe

How much time do you have to run? How far do you go?

M. Chris Fabricant

Well, I run, typically I go a 6-8 miler every weekend, and then try to get another one or two during the course of the week, it really depends on how it goes. When I’m on the road, it’s a lot of Treadmill work, though, in the COVID era, it’s been more difficult, but starting to emerge from that. And so I’m doing a bit more of that.

Joshua B. Hoe

Great. Last summer, I started running for the first time probably in 20 or 30 years. And so I’m like a two or three-mile kind of person. It was a big life change for me. Okay, your book is called Junk Science and the American Criminal Justice System. You dedicate the book to Keith Allen Harward, Stephen Mark Cheney, and Eddie Lee Howard. Let’s talk about each of them independently, as we go through this, because they’re kind of the core of I think, hopefully, the emotional pull of the book. So let’s start with Keith Allen Harward, who is he? How did he get caught up in the criminal justice system, and how did junk science get involved in his story?

M. Chris Fabricant

So when Keith Harward’s case came to us, because when at the … litigation department, when we started to focus on forensic sciences, we decided that bite mark evidence, that the scientific community have weighed in on it as really the junkiest form of forensics that are still being used in the justice system today. And there had already been a number of wrongful convictions when I first started there in 2012. And so what we decided to do is that we’re going to litigate against the admissibility of the use of bite-mark evidence and that we’re also going to search for prisoners locked away around the nation on the use of this really grossly unreliable evidence. And so our paralegals would spend a lot of time identifying potential casework and other scientific research and everything that we’re kind of looking for in terms of our advocacy. One of my paralegals had read Keith Allen Harward’s appellate opinion from the 80s, that it affirmed his capital conviction for the rape and murder – a rape of a young woman and the murder of her husband in 1984, I believe it was. In Newport News, Virginia, there was a young couple that was asleep in their bed, their three young children were asleep down the hall. Somebody broke into their house in a Navy uniform and went upstairs to the couple’s bedroom and bludgeoned them to death, the husband and sexually tortured the wife for three hours while the children are asleep down the hall. So it was a grotesque crime obviously. The woman who survived, Teresa Perron, never really got a good look at the sailor who had committed this atrocity. And there were no eyewitnesses. There was no forensic evidence to speak of. There were no fingerprints that were usable. There was nobody that had a particular motive to do something like this. The only real evidence that they had was that it was a white person, clean-shaven, wearing a navy uniform, around five foot 10 or so, and that was all they had. But in Newport News at the time, and still today is a huge Navy base, and the USS Carl Vinson, an aircraft carrier from the Navy, was drydocked there and there were 1000s, literally 1000s of sailors and 1000s of potential suspects. And because the Ted Bundy case had really brought bite mark evidence into the popular consciousness, only a few years before, and Teresa Perron had said and there were dozens of photographs documenting it that the perpetrator had bitten her thighs. And so the only lead, it wasn’t really a lead, but they believed it to be lead, was this bite mark evidence and so what they did is they took the dental mold and radiographs of 1000s of these Navy sailors that were stationed there at the time. They did this huge dental dragnet and attempted to find the perpetrator by matching the teeth to the bite marks. I don’t think it had ever been tried before and probably hasn’t been tried since. And interestingly, Keith was identified as a potential suspect in that his teeth were matched or attempted to match, and he was excluded as a potential biter and therefore excluded as the potential perpetrator. So months went by, and there were no leads and mounting political pressure from two US Senators and from the local media, and from the local community to make an arrest. Increasingly desperate, the police were, you know, going to great lengths, they were hypnotizing witnesses who had seen a sailor return to the Navy base in a blood-spattered uniform at night. They hypnotized him. They hypnotized Teresa Perron to try to get you know, better evidence, you know, I mean, but memories can only be corrupted by hypnotizing. They can’t be improved over time and certainly not with hypnotizing people. And so, what happened was when Mr. Harward had gotten into a drunken dispute with his girlfriend at the time, she hit him with a frying pan, he bit her on the arm, and they both got arrested. And then Mr. Harward, who was in the Navy at the time, suddenly became a biter. And even though he wore a mustache, you know, he basically fit the description. And then ultimately, the two dentists that had excluded him as a biter changed their mind after this, world-renowned, forensic odontologist, which is a fancy word for forensic dentist named Lowell Levine, who had also testify in the Ted Bundy case, decided that Keith Harward and only Keith Harward could have made these bite marks, to the exclusion of everybody else. And that evidence was enough to overcome the lack of really any other evidence in the case. And really, he would have been executed had his parents not gotten on the witness stand to fight for his life at the sentencing phase. And so fast forward 30 plus years, and it just shows how our Innocence Project clients are one in a million, my paralegal came across the appellate opinion. And if you were skeptical about bite mark evidence, which of course we were, he sounded innocent, you know . . . this is all they had, you know, I mean, like, what are the chances? So we picked up his case. And within a year and a half, the DNA had been discovered in the case, the actual perpetrator had been identified, and he was freed after 34 years of incarceration.

Joshua B. Hoe

34 years, wow. I was particularly shocked by this quote, in the book regarding bite marks, I believe it’s from a case: “There was no established science of identifying a person from bite marks, the technique had not been subject to even the most rudimentary tenets of the scientific method. No hypotheses were tested, no laboratory experiments were conducted, no clinical research.” Would you talk a little bit about the history of the use of bite-mark evidence in the courts and how this became something that’s accepted, despite the fact that there’s literally no scientific basis for it?

M. Chris Fabricant

Yeah, it’s just astonishing. And just to be clear, bite marks are not alone in this.

M. Chris Fabricant

I went back to trace the origins of this particular technique, both when I first started working on it as a litigator, and also in research for this book. And you could see that what was happening is that in the 1960s, in the 1970s, the legal system in our country just kind of grew exponentially. On the civil side, it was a result of personal injury litigation, mass tort litigation, and product liability, which became kind of a cottage industry. And on the criminal side, it was the mass incarceration and the drug war, which exploded the system and so as a result, really had people that became expert witnesses as a career as a profession. And in the criminal justice system, these were primarily forensic pathologists and FBI Crime Lab people that were becoming well-known in the criminal legal system. So in popular culture, Quincy was a very popular show about a forensic pathologist at this time.

Joshua B. Hoe

I’m old enough to remember Quincy, yeah,

M. Chris Fabricant

Me too, right. And so these are crime solvers, you know, and they were busting bad guys. And there was a lot of mythology built up around the forensic scientist as a crimefighter. And so it was something that a career, or a new career that you could actually aspire to, was to be a forensic scientist. And it was kind of exciting. And it was part of the criminal justice system. And there’s always been a lot of fascination around that. And so forensic dentists, if you’re familiar with people being identified through their dental records . . sometimes you’ll see a plane crash or something, and somebody’s burned beyond recognition. And they’re identified through their dental records. Most people aren’t aware that that’s your friendly neighborhood forensic dentist that works down at the medical examiner’s office to identify John & Jane Does. But those folks were not getting into court, they weren’t the Quincys, they weren’t making identifications. They weren’t really part of that culture. They were kind of derivative of it, you know, but they were actually working in those labs. And so, early in this field, you could see that the forensic odontologists were advocating for recognition of their contributions to the legal system. And pointing to bite marks is something that had been overlooked as a potential crime-solving technique. And so what they did is they invented their own credentials, they invented an American Board of Forensic Odontology and started board certifying each other, just by, no tests, to demonstrate, you could actually match somebody to a bite mark or anything else, other than the history of the field. And then they joined the American Academy of Forensic Sciences, and they got their own section in the AFS, called the Odontology Section. And so they had all these credentials that were really built up around this idea of identifying bodies, which is basically legitimate stuff. But what they’re working toward is getting a bite mark case into evidence and using this new technique to expand their fields. And these were not ill-intended folks, these people were recognizing that there was no science, but believed that there was something to be said, you know, in this field. And when they finally found like a perfect test case, what they got is a bite mark that was created on somebody’s nose, right, so this murder victim had her nose nearly bitten off. And it was in cartilage, which doesn’t have the same problems as skin in terms of, recording a bite mark, which changes every minute as a bite decomposes, or in a living victim as they will heal. So you can match one minute and not much the next. No, so that fundamental problem was never even explored in the legal system. But what they did is that they conflated these two sub-disciplines of this field – victim identification, so the idea that you identify people by their teeth, and then this opposite side of the same coin is that, as it was presented, we also identify people by the bite marks those teeth create. And so it makes sense on a superficial level. But if you actually think about it, you know, it’s more like a geologist claiming that because they can identify a rock, that they’re capable of identifying the rock that was used to bash in somebody’s head, right. So totally unrelated fields, but they could make it sound like they were one, and credible. And they already had all these credentials in terms of we’re board-certified forensic odontologists. So they got in this court, the marks case, the first case that introduced this evidence, and it spread like a virus throughout the criminal legal system. And the reasoning that the court, as you pointed out, . . . there’s no science here, there’s not been any research done. We know all this, but this stuff is so elemental, that we don’t even really need to scrutinize it the way we would, whiz-bang technology or something that would be likely to confuse a juror, because a juror can see with their own eyes, whether or not there was a match in this particular case or not. And so that reasoning was used not just for bite marks; there were all these pattern matching techniques, a hair might . . . and tire treads and shoe prints and you know, all the other pattern matching techniques to kind of shield these techniques from typical scrutiny in the courts.

Joshua B. Hoe

It’s interesting, you bring up the tire treads, because the example of this that came to mind when I was reading the book was My Cousin Vinny, when they’re talking about the tire treads. So I mean, I think everybody who’s seen that movie, that is part of what we’re talking about here. Right? This whole notion, this eyeball test, this idea that people just through their experience can look at things and make a conclusion. Is that basically the argument?

M. Chris Fabricant

Yeah, eyeballing evidence in science is never the way that you would be . . . measurement is the basis of most science right? you measure something, you know, to come to a conclusion. And many of these pattern matching techniques are simply eyeballing it using your judgment and subjective judgment to come to that conclusion. You know, the My Cousin Vinny example, I think that that car had positraction, which was something that might have made a difference in the way that a skidmark would be laid down. And that’s a little bit different. So I don’t know enough about it to know that that particular depiction was junk science. But generally speaking, as far as pattern matching goes, for sure, you know, and one of the real problems with this, and we see this with the Keith Harward case and we see this in many other examples I explore in the book, is that these are subjective judgments. Right? And so subjective judgments are susceptible to bias, you know, and that’s just the way the human mind works. This is something that we can’t will away. The National Academy of Sciences has said that and every other mainstream science is taking efforts to mitigate the influence of bias, and one of the most stark examples, apart from the dentist changing their minds, in Keith Harward’s case [is they say] Oh, we do think he matches, nevermind, right, after he was identified as a suspect, but when they were doing it blindly he was excluded. Right? And then this is not just bite marks. So if you think about fingerprints, you know, there was a very well-known, Brandon Mayfield was wrongfully identified through a fingerprint match as the person responsible for the commuter bombing of the commuter train in Madrid, Spain in 2004. And Brandon Mayfield happened to be Muslim and happened to have represented somebody who had been convicted of providing material aid to a terrorist organization, but he’d never been to Spain. And the FBI was positive that it was him, he kind of fit the profile, and then that evidence had been validated by two other, allegedly independently, fingerprint experts, until the Spanish authorities actually matched it to what’s still today believed to be the actual perpetrator. And this was really a shock around the EU because it was fingerprints, that there had been this really high profile misidentification, and a look at like, what were the subjective factors that led to these other experts who kept confirming the wrong match? And the idea is that we’re influenced by factors that are irrelevant to the actual looking at the evidence. Does this evidence match this evidence, right, rather than all the other information about a case that will point you in one direction or another to conclude whether or not there was a match? Right. And so what …. did, after that case, is a very clever experiment. And he sent the casework to five different, really well-qualified fingerprint experts of latent fingerprints from crime scenes and exemplars of potential matches. But what he didn’t tell these experts was that the evidence was from their own prior casework. In other words, they had already come to conclusions around the match or the not match on these particular sets of exemplars. The only thing he changed was the contextual information, right? that pointed one way or another, right, there was an identification in this, or that this confession or something like that, and three-fifths of them changed their minds from their original conclusion, and nothing had changed about the evidence, only the contextual information. We see that in Harward’s case, we see that in Stephen Chaney’s case, and we see that in forensics, and still today, there is no real effort to mitigate the influence and the well-documented influence of cognitive bias. And one of the things that the Innocence Project has advocated for a long time, is the separation of crime labs from law enforcement. And it’s for this reason because if you have forensic experts that have a mindset of catching bad guys, and solving crimes, you’re going to get that type of influence. And it’s particularly problematic with pattern matching techniques because no measurements are taken. There’s no objectivity in the conclusions that are being offered.

Joshua B. Hoe

And, of course, the problem is also that creates kind of a negative incentive. Once the type of evidence is accepted, as you said in the book, there’s really no incentive to conduct research or test the ability of the putative experts. You know, why, as you I think you put it, why conduct research on a technique that’s already been accepted in court? Why indeed? I mean, this is a problem, right.

M. Chris Fabricant

Most forensic techniques, unlike DNA, which is, of course, the exception to most of what we’re talking about, is that they don’t really have applications outside of the criminal legal system. So if you’re, you know, you don’t need a ballistics expert in everyday life, its only use is in criminal court. So if it’s already being accepted, and the most extravagant claims are accepted in criminal court, why risk doing research that might undermine these previously accepted claims that have been accepted for a century, even though today, the National Academy of Sciences has pointed out and many other mainstream scientific organizations have pointed out, that the claims that, you know, one bullet was fired by one gun to the exclusion of every other gun manufactured in the history of time, is scientifically indefensible, right? But it’s still being accepted today. So if you’re gonna do research that tends to undermine that, why would you do that? It’s very disruptive.

Joshua B. Hoe

Okay, so the second story in the book is Steven Mark Chaney. How did he get caught up in the criminal justice system? And how did junk science get involved in his story?

M. Chris Fabricant

Steven Chaney was my first Innocence Project client. And we took on his case because there were a number of conditions that we thought were important to test in Texas, in particular, because there was a new, what became known as a junk science writ. And that was an amendment to their habeas corpus statute that allowed prisoners that have been convicted on alleged scientific evidence to go back to court if they can demonstrate that the progress of science had undermined the testimony at trial. There was a new Conviction Integrity Unit, that was important, that we could talk to about the use of the evidence in his case, and there was the Texas Forensic Science Commission, which was willing to do independent investigations of forensic techniques. And so we were looking for bite mark cases. And I got an email from Julie Lesser who had recently picked up Steven Chaney’s case and said that at his trial forensic dentists had testified that there was a 1 in a million chance that anybody other than Stephen Chaney had left this bite mark on one of the murder victims. And, you know, that was obviously preposterous testimony and we immediately became very interested in taking a deeper look at his case. What we learned was that in the early 80s, in Dallas, which was a very heavy cocaine scene at that time, there was a young married couple.

Joshua B. Hoe

I may actually have lived in Dallas in the early 80s.

M. Chris Fabricant

Right, and MDMA was legal at that time, right?

Joshua B. Hoe

It absolutely was, you could get it in bars, at the bar. Right? Yeah.

M. Chris Fabricant

So it was a very different scene at that time. And it was still an era where cocaine was not considered addictive. You know, I mean, it was just a different era, obviously.

Joshua B. Hoe

I mean, not that I would know, from any experience, right?

M. Chris Fabricant

Yes. Well, I’m certainly not pointing any fingers at you, or anybody. And so this young couple was dealing cocaine out of their apartment. And they had gotten in trouble with their drug suppliers before and had to flee for their lives, you know, a couple of years before this incident, it’s hard to call it an incident, but they had apparently run into trouble with their suppliers again. And then one night, their bodies were found in the kitchen, and they had both been brutally murdered, both had been stabbed at least 18-20 times each. And it was really just a bloodbath in this kitchen. And they were discovered by friends and customers of John and Sally Sweek. And so there was, you know, an incalculable number of suspects, I mean, if you’re in the drug trade, you’re going to make enemies and, and, it’s hard to really nail down who might want to kill you. But what appeared to be from the basic facts was that this was somebody that was executed, and in a way that was meant to send the message to anybody that this is what happens to people that fall behind on their drug debts. But the police had no real evidence, they had no eyewitnesses, they had, you know, 60-70 different latent fingerprints that were most of them bloody, but that didn’t have any potential matches to anybody. And, they really had no evidence other than they identified this person initially, that was a drug supplier and had come looking for John and Sally Sweek, days before they were murdered. But there were no fingerprint matches to him. And then, and somehow, they just kind of let him go. And then about a week after the homicide, a so-called friend of Steven Chaney’s had contacted the police and claimed that Mr. Chaney had a motive to murder both of these people because he owed them money, a drug debt of $500, which he thought was motive enough to murder them both, even though Steven Chaney had never been accused of any violent crime, he had two misdemeanor marijuana arrests on his record, he was 30 years old. He was supporting two kids. He was an ironworker at the time. And he presented nine alibi witnesses at trial. But what happened is that once he was identified as a suspect, you could see he became a bull’s eye and they started painting a target around him. And so there was shoe print evidence that said that his shoe could not be excluded as one of the bloody footprints in the footwear evidence in the kitchen, where the murders had occurred. They claim that a presumptive drug test had shown that there was blood on his sneakers, his fingerprint was found near the bodies, but he had spent a lot of time at the Sweeks’ apartment because he was somebody that was buying cocaine from them at the time, as he used cocaine. And that fingerprint was not bloody, unlike so many of the others. And then there was this injury on John Sweeks’ forearm, this U-shaped injury and there’s a photograph of it in my book. So I invite readers to take a look at it and see if it looks like a bite mark to you because it doesn’t to me. But they decided that this injury was a bite mark. And then that was all they decided. And they decided that it had been inflicted two to three days before this murder, right. So really not even that relevant to who might have actually committed this horrible crime. But once Steven Chaney was identified as the suspect, the dentist Jim Hales at the time, was the Chief Forensic Odontologist for the Dallas Medical Examiner’s Office, who decided that Steven Chaney’s teeth were consistent with having made this bite mark, they couldn’t say at that time that he was the only person in the world who could have made this bite mark, but it was consistent with them. Then we see how this opinion evolved over time. And we see this in a lot of wrongful conviction cases. And you see it in a lot of cases period, is that as the case gets closer and closer to trial, more and more pressure is put on the forensic expert to have more conclusive opinions, to have more damaging evidence to present at trial, and often are persuaded that this defendant is guilty, you know and that they’re helping put away a bad guy. When you see the evolution, I document this evolution in the book about how a bite mark was, at one time consistent with, then became Steven Chaney. And then at trial, it became one in a million that anybody other than Steven Chaney had committed, had created this bite mark, and then the time changed from two or three days before the trial, to at or near the time of trial. And that evidence was enough. Plus this other kind of thrown in junk science that was used, a polygraph and the shoe prints and the presumptive drug test to overcome nine alibi witnesses, including, you know, a woman named Leonora Chaney, who became his wife, and was one of his alibi witnesses and stuck with him for the next 30 years that he spent in prison. This is a result purely of junk science.

Joshua B. Hoe

Yeah, I mean, it’s amazing to me that you’ve got a situation where you’ve got nine alibi witnesses. And then you’ve got this bite mark that supposedly happened before the crime was committed. And somehow that becomes a one-in-a-million proof to the jury that this person is the only person who could have committed the crime. You really couldn’t write anything more terrifying, and upsetting in a lot of ways. We’ve talked a lot about forensic testimony related to bites. But later in the book, you take a detour into arson investigations, and a prosecutor says about criminal trials: “the defendant has two strikes against them the minute the jury is sworn in, proving a case beyond a reasonable doubt sounds like a high bar, but jurors tend to believe what prosecutors tell them.” It’s an interesting statement, given the mythology, I think most people believe there’s a certain truth to our system; you’ve been in and around a lot of trials. How would you unpack this reality of presumed guilty versus the notion of presumed innocent?

M. Chris Fabricant

You know, most people that are indicted and tried for crimes are guilty, at least of some of the factual allegations against them. Imagine the society we lived in where that wasn’t true. But the – and we talked earlier today, this percentage of folks that are likely innocent, are 10s of 1000s of people given the volume of what our justice system looks like today in this country. So the idea that, that somebody is presumed innocent when they’re on trial is really not true; meaning that the idea is that most people, the judge, the prosecutor, the jurors, the gallery, you know, I mean, everybody but the defendant and the defense attorney are presuming that this person did something, that they weren’t picked out of a phonebook. And that really, the trial is about proving that guilt. And that’s the reality. I talk a little bit about that, in the context of the arson detour that you called it, in the book, is that one of the original arson prosecutions that began to unravel the mythology that had been used to wrongfully execute Cameron Todd Willingham, which is a case that I talked about in the book.

Joshua B. Hoe

I actually remember the story about him in the Texas Monthly when I was living in Texas around that time.

M. Chris Fabricant

Right, right. And so what’s astonishing is that once the arson mythology had been debunked, the number of reported arson cases in this country reduced by nearly 40%. And so the idea wasn’t that people were, you know, deliberately setting fewer fires, it’s that they’re fewer being called arson because they recognize that this was not good evidence of arson. And what the prosecutor in the case that I talked about, the Gerald Lewis case, was really the first controlled experiment that had been ever done in an arson investigation, was done in the context of a capital case in Florida. And John Lentini, one of the characters in the book was hired by the prosecution in that because the defense had presented in that case, a fair amount of evidence of innocence, even though there was a lot of circumstantial evidence that pointed to guilt in that case, and the prosecutor, who ultimately I quoted in that saying that, you know, he understood that the defendant has two strikes against him when he’s starting, and this is a capital prosecution. There were six dead people in this case. So it was a very, very serious case. And what was, you know, to his great credit, he did not railroad the case forward, even though all the traditional arson indicators that were thought to be arson indicators at the time pointed toward a deliberate fire. And what John Lentini had suggested, and what this prosecutor actually did was the first controlled experiment. That was, what they did is the house that was next door to what they thought was the crime scene was nearly identical. And they recreated all the conditions of the crime scene house before it burned down in the house next door, and they burned down the house and in an experiment to show whether or not these signs that they had looked at like something like alligatoring on the floor and pour patterns on the ground that looked as though somebody had used the liquid accelerant, like gasoline to light this fire. And things that they believe indicated multiple points of origin, in other words, that somebody had set a fire in a number of places in the house which would suggest, of course, that that was a deliberate fire, all these things that have been used to prosecute other people that had been used to put Cameron Todd Willingham to death, were part of the underlying basis of the capitol indictment against Gerald Lewis. So when they conducted this experiment, all these telltale signs on, they knew had not been a fire, that had been deliberately set using accelerants. In the experiment, they saw the same indicators, multiple points of origin in a fire that only had one origin, right, that alligatoring on the floor, even though there was no accelerant used, or patterns or something. It looked like pour patterns that weren’t pour patterns. And ultimately, that prosecutor dismissed the indictment, which you know, was, you know, a remarkable and unusual prosecution and saved a life during that. And really, how many more lives were potentially saved as a result of a scientific experiment that could have been done anytime and never was. And that’s really what the Innocence Project has been advocating for a long time, is that we have to have something like the FDA, that tests toothpaste, aspirin, toilet paper, anything that is going to be used by American consumers, for public safety reasons, right? We don’t have anything like that in forensic sciences. We don’t have an agency that is doing the scientific validation research outside the context of a criminal prosecution where there aren’t the pressures that we’ve been talking about, to validate some of these claims that are being made routinely in criminal court, and that it gets tied up in the adversarial system, which is a terrible place to try to decide what’s valid science and what isn’t. And so I use a couple of those cases, including Nancy Grace’s final case.

Joshua B. Hoe

That was pretty disturbing too.

M. Chris Fabricant

To kind of demonstrate, here’s where we could be. And here’s where we aren’t, you know, and that’s like, what I think is really central to the arson discussion, is just how radically it was changed as a result of one scientific experiment.

Joshua B. Hoe

So we have kind of a presumption against the defendant, we have this massive array of State forces on one side, trying to make sure someone gets convicted. We have a presumption that people are afforded good counsel. But I think even when you have good counsel, I think you mentioned in the book that at one point, you were handling hundreds of cases at a time. And I know I partially got into being an activist, not just because I’ve been incarcerated, but because I remember standing outside of a courtroom and seeing that many public defenders were doing 30 cases, and it looked like in a day on the docket. And I was like, how can that work? You know, and so we have all these things. And then there’s also this principle of finality, which is really, I think we’ve come across this a couple of times on the podcast, but it’s something that just blows my mind. Can you talk about this principle and why it’s so problematic?

M. Chris Fabricant

Yeah, you know, the principle of finality essentially means that once a jury comes back with a guilty verdict, the idea is that that’s the truth. That’s the case, you get one appeal. And then that’s it, that there’s no going back and taking a second look, even though we use science all the time in criminal trials, and that science is a process that is always moving forward. And the criminal legal system is based on legal precedent that doesn’t really move forward. The principle of finality had been used to justify sawing off avenues of post-conviction relief for a long, long time. And what was so disruptive about the advent of forensic DNA evidence and the establishment of the Innocence Project was really the challenge to this bedrock principle of our justice system is that the jury verdicts are the last word. Because, you know, this is really the result of the intake criteria that the Innocence Project initially had. This was and it had been for 20 years, 30 years, that there wasn’t going to be a subjective evaluation of the quantum of evidence against people that wrote in for our help. In other words, we weren’t counting how many eyewitnesses there were, if there was a confession, and there was other evidence, routine cases that six eyewitnesses that somebody confessed in great detail to the crime. The only criteria was if biological evidence can be found and tested, and that came back in a way that excluded the defendant, would that prove innocence? That was the only criteria. And what that resulted in was the discovery of how unreliable eyewitness identification actually is and how unreliable so many of these forensic techniques that have been used and thought to be invaluable were, that people actually falsely confess to crimes that they didn’t commit. None of that was thought to be even a thing at the time, right, and that the justice system, with notable exceptions, was essentially infallible. And so you had these forces that came together, which is science that was overruling, you know that the justice system’s principle of finality, and then you had the buildup of the carceral state, as a result of the drug war and then sawing off of avenues of post-conviction relief by the 1996 anti-terrorism and effective death penalty act, which effectively excluded federal courts from reviewing state court convictions where the overwhelming majority of violent crimes are prosecuted and where the overwhelming majority of wrongful convictions occur. And so the principle of finality is used to justify, it’s still today, by prosecutors and by courts to deny the post-conviction relief. And some of the case law that’s been built up around this that points to that, has accepted crazy post-conviction theories by prosecutors to explain away exculpatory DNA evidence or to deny compelling evidence of innocence on procedural grounds. Right, and so technicalities that won’t actually get to whether or not this person was guilty or innocent. Has there been a miscarriage of justice? Has there been an unfair trial?

Joshua B. Hoe

Seems like there’s also another perverse incentive. You mentioned one prosecutor’s office in the book that made it an office policy to dispose of all evidence after a conviction, which then makes it impossible to test the DNA because there’s no DNA, no biological evidence to test, it seems like they’ve created a perfect loop, in a sense.

M. Chris Fabricant

Yeah, that was the Claude Jones case in Texas. It is one of the four cases that argue were wrongful executions, all committed in Texas.

Joshua B. Hoe

What a shocker, it’s in Texas. Abbott just presided over his 55th execution just last week, I believe.

M. Chris Fabricant

Yes. And as we are sitting here today, you know, Melissa Lucio is scheduled for execution next week, and there are grave doubts about her guilt in this case. And it’s also again, in Texas, and its avenues again, going to have to make that decision. And when you go back to the Claude Jones case, in that Claude Jones was somebody that was, a quote-unquote, career criminal, and was not a very high profile case, it was a robbery that turned into a homicide at a liquor store. And the only physical evidence that was in the case was a hair microscopy match. And that put him inside the liquor store, and therefore the trigger man in that case, and that made him eligible for the death penalty because the only other evidence against him was, you know, the alleged co-conspirator testimony or snitch testimony. Then the other two people that were allegedly involved in this both are free today, I mean one may actually still be in, but one of the other people that pointed the finger at Claude Jones is free. And what the Innocence Project had done and advocated for was after it became known that hair microscopy was so unreliable, that they were looking at this execution that was based primarily on hair microscopy, it actually went and found the hair that was used to place Claude Jones in the liquor store. And to manage to convince one court after many, many courts had denied it, according to the principle of finality as a block, you know, as a reason not to know the truth. And, you know, courageously one judge actually ordered the DNA testing to be done. And it showed, in fact, that it was not Claude Jones’ hair that had placed him at the crime scene, you know, and before that the prosecutor [wanted] to avoid knowing whether an innocent person had been executed, pointed to the principle of finality, saying that the jury’s verdict should be final. And to me, that’s just astonishing that we’re so afraid of the truth.

Joshua B. Hoe

This blows my mind. Okay, so the third major character in the book is Eddie Lee Howard, this one actually upset me quite a bit. How did he get caught up in the criminal justice system, how did junk science get involved in his story?

M. Chris Fabricant

Howard’s case is really about structural racism and less about junk science. I talk about a number of cases in the book about black men that were accused of violating white women, and that, you know, this plays on racist tropes that have led to lynchings and wrongful executions for the last hundreds of years. And what happened with Eddie Lee Howard’s case was that an elderly white woman was raped and murdered and the perpetrator appeared to have attempted to burn down her house to hide evidence of the crime; no witnesses, no forensic evidence, really nothing to point to any particular perpetrator, this person had no known enemies. And so what the police did in Mississippi, and this was in Columbus, Mississippi, a small town in the middle of the state. [They] basically started rounding up black people as potential suspects for this crime. That was really what they were going with, the quote-unquote, usual suspects. Eddie Lee Howard was identified as one of these people, but they had no real evidence against him, but they decided that you know, he was good for it, or at least good enough. And what the problem was, is that the victim had already been autopsied and had all of her organs removed and brain removed, and she was buried unembalmed in the ground for four days before he was identified as a potential suspect. What was astonishing is that the same time that they decided that Eddie Lee Howard was a suspect they took him straight to the dentist to get a mold of his teeth taken, and then they ordered the body to be disinterred. Even though there was no evidence at autopsy, we have photographs and documentation showing that there was no evidence of bite marks anywhere on the body. But they decided, get this dental mold and disinter this body or the remains of this body and see if you can find a bit mark and match it to Eddie Lee Howard. This is what you have when this type of junk science is already admissible. We know that we can almost interpret any kind of entry as a bite mark. And we’ve got the perfect expert to do it. The notorious Dr. Michael West, who is one of the most notorious forensic experts in the annals of Forensic Sciences in this country. He had already been totally discredited by the time this . . . came along, but what he did was he got out his black magic, you know, lights and the so-called West phenomenon and you use ultraviolet lights to discover bite marks that were totally undocumented before, and he matched three of these bite marks to Eddie Lee Howard to the exclusion of everybody else on the planet. And that was enough to send Howard to death row and Parchman Prison Farm in Mississippi, one of the most notorious prisons in the world. And, it was just on Dr. West’s say so they didn’t even have any photographs of the alleged injuries at trial. There were no dental molars, there was no demonstrative evidence at all, it was just somebody who was claiming to be an expert, claiming that there were bite marks on this body and claiming that Eddie Lee Howard matched them; that was enough for the conviction. And what that shows in addition to, the racism that underlies the entire prosecution and you know, to be clear, the entire criminal legal system, but that just the idea of Forensic Sciences was enough to convict and enough that this person was declared an expert witness, he was a board-certified member of the American Board of Forensic Odontology. And he had all these credentials that suggested he was a credible witness when he had zero credibility. And it was a monumental struggle to get him off death row, and one of the things that occurs to me a lot, in this type of litigation is that when we have non-capital cases, and we’re working on people’s cases who aren’t sentenced to death, is that I’m not sure if Eddie Lee Howard ever gets out of prison if he hadn’t been sentenced to death, because you have to take it more seriously than somebody who’s just thrown away for the rest of their lives. If somebody gets life without parole, those cases don’t get the kind of attention and lawyering that a death row case will, you know, mean, and that, to me, is chilling. And it makes me when we’re talking about how many potentially wrongfully convicted people that are in this country. And think about the life without parole cases where you don’t get teams of really good lawyers and a lot of people that are digging into the case, ways that it had never been dug in before. You know, for example, in the Howard case, the fact that the victim had been, you know, the body had been totally mutilated during the autopsy, and buried unembalmed and that there was no evidence of bite marks before the autopsy – that West was not even cross-examined about that at trial at all. The first time that anybody had asked him about that was when I was doing the deposition that I write about in the book, which is this crazy deposition where he’s calling me an asshole . . .

Joshua B. Hoe

It is a crazy deposition.

M. Chris Fabricant

They get a madman that had been put on the witness stand that put this person on death row. So it’s, in some ways, it’s funny if it wasn’t so serious. I worry and think about a lot, you know, life without parole on these wrongful convictions and how hard it is to get the kind of teams of lawyers that you need to really do quality post-conviction investigation work, you know, meaning what it really takes to overcome the principle of finality. And, you know, the Innocence Project is, certainly compared to the scale of the justice system, a tiny organization. You can’t rely on a handful of lawyers that I work with and who work in the innocence network, you know, around the country to free the innocent; it is just not enough. We have to have better upstream fixes.

Joshua B. Hoe

I think you mentioned throughout the book, it might be a non-exhaustive list, but hair and fiber, ballistics, prints, tire treads, arson investigations, blood spatter evidence, handwriting, even fingerprint evidence, but all of these are still pretty much admissible. And I think if you asked most people in the country, most would consider them valid I think probably because of shows like CSI and the ones you mentioned before, Quincy, stuff like that. Does the media bear any responsibility for the continuation of this kind of behemoth of junk science?

M. Chris Fabricant

Oh my god yes. What I’m trying to do with the book is create a new genre of NOT True Crime?

Joshua B. Hoe

I like that.

M. Chris Fabricant

That’s what we need. The example that I like to point to when you talk about the CSI effect, is we have two cases that we’re currently – Well, one that we’re still litigating, one we’re not, that we became aware of as a result of watching the Forensic Files. And the lawyers in my department looking at this [saying] it seems like this person sounds innocent. You know, this is being depicted as: look at this whiz-bang technology that was used to catch the bad guy. One of those cases is Jimmy Genrich in Colorado, which we just did the evidentiary hearing. It’s a case that’s talked about a little bit in the book, which is a series of bombings in Colorado in the 80s and 90s. The only evidence, the only physical evidence, and really the only evidence in the case is like a little scratch mark on a detonated bomb that was made by Jimmy Genrich’s wire stripper to the exclusion of every other wire stripper ever manufactured in the history of time. And that’s the only evidence and scientifically defensible opinion that was offered at trial. And then another case, Alfred Swinton in Connecticut, where he was thought to be a serial killer. And they tried to put eight bodies on him. But he was only convicted on one of those murders because a series of murders of prostitutes in Connecticut had been going on for some time during that era. And Alfred Swinton was identified as a suspect, and in one of the cases, there was an alleged bite mark on the victim’s breast. And that was depicted as definitive evidence, both at the trial and on the Forensic Files. And then when we saw it, we picked up his case, about 60 months later, he was exonerated and freed. In a sense, he’d never been convicted in any other crimes. And you know, still, years later, you could still watch it on YouTube, that this was definitive evidence about Alfred Swinton’s guilt. I wrote to Bill Curtis at the time, you know, who was the host of the show. I was like, hey, you know, he’s innocent. How about we take that down? And we see this, actually, there’s a CSI episode that shows bite mark evidence is definitive evidence of guilt. And there’s, back in the day, there’s a Colombo episode showing bite mark evidence; it contributes to mythology that’s built up around forensics that are essentially infallible. And, you know, given the two strikes that defendants have, when they walk into court to begin with, any kind of forensic science evidence like that, is going to be enough to convict almost anybody of almost anything.

Joshua B. Hoe

So we talked about how the book, in a way, is a story of three people that you dedicated the book to. The end of your book rightfully celebrates the exoneration of these men, one of whom had to actually wear leg irons for years, despite being innocent. But to me, it still kind of felt very sad. I felt sad for the men who’d lost most of their lives. I felt sad for us as a society for continuing to invest more in the certainty of punishment than actual justice. Where did finishing the book leave you in terms of your feelings about going through all this and what had happened?

M. Chris Fabricant

I work hard to not be too cynical about my work, you know, and so what fuels me to go to the office every day is my outrage at some of the things that have happened to our clients. And this goes back to my time as a public defender, it goes back to my mother’s drug arrest, you know, in the 60s. You can’t spend time, and I think you ask any public defender standing next to people who have been traumatized by systemic racism in this country, time and time again, and this is just an extension of that, and not have a sense of deep injustice about what’s happening every day in criminal courts around the country. And it’s not just the searing injustices that I write about, but it’s the day in day out, where people have to plead guilty to crimes being committed because they can’t make bail or presumptive drug tests are used to claim that somebody had drugs when they didn’t have drugs or people that are arrested for low-level misdemeanors and can’t fight those cases from the inside and have to take a plea to get out. And, you know, that happens. And I [write] a little bit about this in the book, about my time as a public defender with the Bronx Defenders in the South Bronx, where [at] my first arraignment shift, at least five or six people had been arrested and spent nights, sometimes two or three nights in jail, entirely innocent of any crime at all. And that was mind-blowing to me.

Joshua B. Hoe

Especially given Rikers.

M. Chris Fabricant

Rikers is, you know, a day in Rikers. It’s a life-altering experience. I think it’s important to point out, as incredible as the stories that I write about are, the day in and day out, injustices are in many ways, you know, equally life-altering. And that’s what makes me go to work every day. And no, I didn’t feel happy, and I wish I could give the story a happy ending, but . . .

Joshua B. Hoe

It kinda is a happy ending, I don’t mean to make it sound like it’s not a happy ending, but there is some sadness there, some pretty profound, for me, at least.

M. Chris Fabricant

These are great losses, these are great losses. I mean, just imagine having most of your life just wiped out, and spending that in prison. What a lot of people at the Innocence Project will point to is the astonishing grace that so many of our clients demonstrate when they’re out, the lack of bitterness. And, you know, the savoring of freedom, you know, is really astonishing, and those moments fuel a lot of the work that we do. What is less talked about, but it’s also equally true, is the post-traumatic stress that our clients have experienced, and the lingering effects of a grave injustice like that, is really hard to undo. And, that’s why the failure to adequately compensate the wrongfully convicted is such an outrage that is still a persistent problem in this country and the denial of innocence of so many people that haven’t been able to conclusively demonstrate their innocence. But every sign points to this, and sometimes they’ll be coerced into pleading guilty just to get out of prison when evidence plainly establishes their innocence. So a lot of progress is being made by organizations like ours, kind of a slow understanding of the costs of mass incarceration, but it’s certainly not being done fast enough. And if you look at, we have the highest incarceration rate in the world in the United States, and we have amongst the highest rates of violent crime. So clearly, mass incarceration is not working at reducing crime.

Joshua B. Hoe

I make this point all the time. I’m always saying, Look, if traditional policing is the answer, we spend $120 billion on police every year in this country. If incarceration is the answer, we spend $80 billion a year on incarceration in this country. You know, if these are the answers, why is there still such a problem? They point to small reforms we’ve passed, but is that really enough to disrupt this gigantic enterprise that’s been created?

M. Chris Fabricant

Apparently not.

Joshua B. Hoe

It’s just mind-boggling to me. So my friend Amanda Alexander always talks about the power of dreaming big and of having freedom dreams. This season I’m asking folks what dreams they have about changing our system. You’ve mentioned a couple of the things that you all have been hoping for. Is there anything else you’d like to say about that?

M. Chris Fabricant

Yeah, apart from what I’ve already said, you know, is that we need to end the drug war today and that we need to stop treating a public health crisis as a criminal problem and address the public health issues that underlie it. And we have to stop using junk science.

Joshua B. Hoe

Hey, man, I also like to ask people if there are any criminal justice-related books that they like and might recommend to our listeners, do you have any favorite books?

M. Chris Fabricant

Yeah, I have many favorite books.

Joshua B. Hoe

You can see that I read a lot

M. Chris Fabricant

Just Mercy is a fantastic book. An American Marriage is not often pointed to as a criminal justice book, but it is, and it’s a wonderful read, and really one of the most moving books I’ve read. So those two I think, are, I don’t think you can do better than those two.

Joshua B. Hoe

I always ask this; how would you recommend people find your book? Do you have any particular place you’d like for people to look more than others?

M. Chris Fabricant

I would love it if they looked for the book, period.

Joshua B. Hoe

I always ask the same last question. What did I mess up? What questions should I have asked but did not?

M. Chris Fabricant

I think that you’ve asked a lot of good questions. I’ve appreciated the interview and I appreciate the advocacy work that you’ve been doing.

Joshua B. Hoe

Thanks so much. I always like to hear that I didn’t mess up, but you know, I’m always willing to listen to what I missed. Thanks so much for doing this. It was a real pleasure to talk to you. And really, I got lucky in that I get to read a lot of books and they’re almost all pretty good books, but I found this to be a really powerful read. So hopefully everybody will give it a read.

M. Chris Fabricant

Thanks so much, Josh. Thanks for having me on.1

Joshua B. Hoe

Now, my take.

People want someone to pay for the crimes that have been committed. Prosecutors have police working for them and have decided advantages over the defense. 97% of people accept plea bargains, courts bend over backwards to allow all evidence, even the most questionable evidence, [to be] presented on the side of the state. Everything from hair fibers to bite mark evidence, and courts go out of their way to ensure that all decisions are final, even when there’s a real chance that the outcome might have been wrong. Appeals are often denied on technicalities and just to be 100% certain nothing bad can happen that might upset the state’s conviction apple cart. Some prosecutors even destroy all of the evidence involved in a case after they get a conviction. And still, we pretend that our justice system is the envy of the world.

As always, you can find the show notes and/or leave us a comment at DecarcerationNation.com.

If you want to support the podcast directly, you can do so at patreon.com/decarcerationnation; all proceeds will go to sponsoring our volunteers and supporting the podcast directly. For those of you who prefer to make a one-time donation, you can now go to our website and make your donation there. Thanks to all of you who have joined us from Patreon or made a donation.

You can also support us in non-monetary ways by leaving a five-star review on iTunes or by liking us on Stitcher or Spotify. Please be sure to add us on Instagram, Facebook, and Twitter and share our posts across your network.

Special thanks to Andrew Stein who does the podcast editing and post-production for me; to Ann Espo, who’s helping out with transcript editing and graphics for our website and Twitter; and to Alex Mayo, who helps with our website.

Decarceration Nation is a podcast about radically re-imagining America’s criminal justice system. If you enjoy the podcast we hope you will subscribe and leave a rating or review on iTunes. We will try to answer all honest questions or comments that are left on this site. We hope fans will help support Decarceration Nation by supporting us on Patreon.