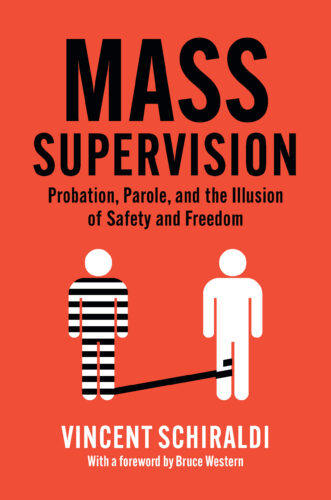

Joshua B. Hoe talks with Vincent Schiraldi about his book “Mass Supervision”

Full Episode

My Guest – Vincent Schiraldi – author of Mass Supervision

Vincent Schiraldi is the founder of the Center on Juvenile and Criminal Justice and the Justice Policy Institute and has served as the Director of Juvenile Corrections in Washington DC, Commissioner of the NY Department of Probation, and Commissioner of the New York City Department of Corrections. He has been a senior research fellow at the Harvard Kennedy School and co-founder of Columbia University Justice Lab. He is currently secretary of the Maryland Department of Juvenile Services and the author of the new book “Mass Supervision: Probation, Parole, and the Illusion of Safety and Freedom“

Watch the Interview on our YouTube channel

You can watch episode 145 on our YouTube channel

Notes from Episode 145 – Mass Supervision

The books Vincent Schiraldi recommended were:

Lenore Anderson, In Their Names: The Untold Story of Victims’ Rights, Mass Incarceration, and the Failure of Public Safety

Danielle Sered, Until We Reckon: Violence, Mass Incarceration, and the Road to Repair

Full Transcript

Joshua Hoe

Hello and welcome to Episode 145 of the DecarcerationNation podcast, a podcast about radically reimagining America’s criminal justice system.

I’m Josh Hoe, and among other things, I’m formerly incarcerated, a policy analyst, a criminal justice reform advocate, and the author of the book Writing Your Own Best Story: Addiction and Living Hope.

Today’s episode is my interview with Vincent Schiraldi about his book Mass Supervision. Vincent Schiraldi is the founder of the Center on Juvenile and Criminal Justice and the Justice Policy Institute and has served as the Director of Juvenile Corrections in Washington DC, Commissioner of the New York Department of Probation, and Commissioner of the New York City Department of Corrections. He has been a senior research fellow at the Harvard Kennedy School and [was a] co-founder of Columbia University’s Justice Lab. He is currently Secretary of the Maryland Department of Juvenile Services. And this is his third visit to the DecarcerationNation podcast. He’s here to discuss his new book Mass Supervision: Probation, Parole, and the Illusion of Safety and Freedom. Welcome back to the Decarceration Nation podcast, Vincent Schiraldi.

Vincent Schiraldi

Thanks for having me back on Josh.

Josh Hoe

My pleasure. This is your third visit, as I just mentioned, instead of having you kind of repeat what I always do, which is your origin story, why don’t you share something people might not know about you? Maybe that isn’t even criminal justice-related? Do you have hobbies or anything you like to do?

Vincent Schiraldi

I don’t really have a life outside criminal justice. That’s my problem. I’m just a criminal justice nerd. But I can tell you my origin story in probation if you’d like to hear that. So I had, you know, I had worked, I ran the juvenile system in Washington, DC, for five years under Mayor Williams and, and Mayor Fenty, and was done, I was going to drop the mic, go back into the nonprofit world where I really had spent my whole career prior to DC. And I got recruited by the Bloomberg administration, out of nowhere, I wasn’t looking for a job. I was, you know, going back. And so I met with Mayor Bloomberg, and it was kind of a super interesting interview. He had been getting some criticism for not hiring New Yorkers to run his departments. And here I was, as you can tell from my accent, born and raised in Brooklyn, went to Catholic High School in my neighborhood, went to, you know, Catholic High school and State University of New York, and NYU, so he was very happy about my New York bona fides. And now it’s time to talk about probation for a second. And he just takes this breath, sort of looks away and says, So tell me about probation. And it was like, you know, how fascinated Am I to talk about reforming New York City probation departments? And he said, What do you think about it? And I said, Well, not much. I think it’s a poor service given to poor people. And most politicians, don’t care about it, don’t know much about it. And he said, Well, tell me more. Well, you know, what would you do? So well, let me let me put it to you this way. If this probation department didn’t exist, and I came to you with $80,000,00 and 80,000 troubled and troubling souls and said, Do whatever you think you can to help folks turn their lives around, make the city safer, rehabilitate people, I’m pretty sure what you wouldn’t do is run out and hire 1000 civil service protected bureaucrats to have them piss in a cup once a week and tell him to go forth and sin no more. He said, No, I wouldn’t do that. I’m sure I wouldn’t do that. And I said, Well, I haven’t been to your department. So I’m not saying anything about you in particular. But I bet that’s what you got. And it with three Deputy Mayors in the room, one of whom had been checking email the whole time. And he finally looked up at this moment. And the mayor looked at them and they said, Yeah, that’s pretty much what we got. And so I you know, and I want to give you that story, not just because you asked me for something interesting, but because I think that’s what most politicians think about probation, which is kind of not at all. And then we started spitballing. We should privatize it, we should do this, we should do that. And I said, Okay, I can work here because I didn’t have an answer, but at least people are open to a discussion about it that was outside the box in ways that I think typically we don’t do. Typically our discussions about probation and parole are very very tepid, if at all.

Josh Hoe

You’ve actually worked for several different mayors. I’ve always kind of had this theory, especially in New York City – I’m also as I think we’ve talked about before, from New York – although you can’t tell from my voice. Manhattan. I’ve always kind of assumed

Vincent Schiraldi

Manhattan guys always had those suspect accents, you know?

Josh Hoe

Yeah, I mean, it’s true. Everyone’s like, you don’t sound like you’re from New York. I’m like, oh, you know, I was born at Roosevelt Hospital, I don’t know what to tell you. You know, I’ve always kind of assumed that no mayor has a real chance to reform New York City in the way that they say they’re going to in terms of the police, and you know, all law enforcement functions, because in a lot of ways, the police really run New York City. And I don’t know if I’m right about that or not. But you’ve been much more of an insider than I have been. What are your thoughts on that?

Vincent Schiraldi

Well, there definitely were little commissioners, and big commissioners, education and police were big commissioners, I’m gonna guess you know what probation was? So I flew under the radar, which was actually not a bad thing, when you tried to make some profound criminal justice reforms, especially in a city where there were lots and lots of stop and frisks. And there was a very sort of testosterone-driven approach. I was able to have my conversations with the mayor, outside of the major spotlight, and you know, we were able to get a lot of stuff done, we cut the number of people on probation, violations dropped in half, we increased six fold the number of people who were getting early discharge. So we were able to move the ball, not as much as I suggest in the book, but way more than nothing.

Josh Hoe

So I feel like I’ve got to ask you this question, even though we mostly want to talk about your book, and we’ve already gotten into parole and probation to some extent. But I have to ask, at least for a very short period, at the end of the last New York mayor’s term, you are the Director of Corrections in New York City. You know, Rikers, obviously one of the most notorious jails in the United States, is there. Can you summarize your takeaway from that experience? And what do you think the prospects are? Or do you think things could get better? Or if they’re going to get worse?

Vincent Schiraldi

Yeah, I mean, I would call it heartbreaking. It was seven months, it was the last seven months of Mayor de Blasio administration, and it was the peak of the Omicron variant of COVID. Staff were calling in sick by the droves. It was on weekends, especially long weekends, we had about a third of my staff not coming to work. So that meant that at those times, and other times as well, there were whole living units with no correctional officer on, so you got 50 guys sleeping on beds in a day room, essentially in a big dorm room. And every pillow, every mattress you pick up has a shank under it, you know, a homemade knife, because you’d have a shank in that room. Then a couple of times the guys were standing right next to their beds, and I picked up the pillows and they said, Yo man, give me a CO. I’ll give you my shank. Until then I gotta protect myself. And that means no fistfights. Right, there’s only knife fights because you don’t want to be the last guy to pull your knife. And so, you know, it was that kind of terrible. Staff morale was through the floor. We had dozens and dozens and dozens of people working triple shifts, exhausted at work, falling asleep, sometimes walking off a shift saying I cannot responsibly do this job right now because I’m too tired. And in situations like that, you know, they had added 14,000 cameras to Rikers Island, because of a lawsuit that had been going on for several years before I got there. And so you got to see everything and you got to see people choke on an orange and die because there was no CO there. And the person in the bubble wouldn’t let them out. Because, you know, they were banging on the door saying we need a doctor, we need a nurse to help this guy and didn’t decide to let them out till the guy died, or no time when somebody smoked. What was probably a mailed envelope soaked in some drugs and overdosed and died again while incarcerated people were trying to revive them and there was no correctional officer there to sort of take charge and get the medical help. So it was really kind of beyond heartbreaking. The advocates, and the correctional officers hated each other. And so there was very little opportunity for middle ground. And each thought they had to fight as hard as they could, pull as hard as they could in different directions in order to move the ball the way they wanted the ball to move, as opposed to kind of getting together and saying, you don’t want to be unsafe at work, we don’t want incarcerated people to be unsafe. How can we figure this out? That wasn’t happening in my little seven months, I really couldn’t make it happen. Although we did do one thing that if you want, I can describe to you that gave me some hope. We brought on a couple of consultants who had previously worked for the Vera Institute of Justice that were focused on young adults, not juveniles, but young people in prisons. And we sat them down with the incarcerated young people and the staff. We had hoped to do it together. They hated each other so much, there was no way they would do it together. So we said we’ll do it separately. Okay, guys, we want to design what a safe unit would look like and what a decent unit should look like and at that time, there were over 400 stabbings and slashings in Rikers that year, and violence on the adolescent unit, which was 18 to 21 year olds, was three times higher than it was in the rest of Rikers. So it was three times a very violent place. And so, we sat with the young people and sat with the staff. We wanted to pull the staff out and have them sit in a conference room and go through a PowerPoint. But we had so few staff that we couldn’t do that. So we ended up bringing PowerPoint on blown up boards on to the unit. And even though people said they didn’t want to work with each other, you bring a bunch of PowerPoint slides onto a unit. Everybody gravitates around them. And eventually, they started planning this unit together. It was very program heavy, it was very restorative practices heavy. instead of stabbing you use your words, things like that. We physically painted it and brought people in from the outside, a lot of religious people came into the community. And no violence, you know, ran for four months while I was still there. No, no assaults on staff, no fights, we found one shank. And I remember the day that happened, the Warden called me up and she said we found a shank, she was very, very nervous that I was going to cancel the program. But she said two things happened once we found it that never happened before. We had a big circle with all the staff, all the young people were talking it through, the young person whose shank it was confessed. That’s number one. And number two, he apologized. And then the rest of the conversation was about whether he should stay on the unit or not. He said, I just really didn’t believe that you didn’t need a shank to be in here. So I had one and I apologize. And they kept him in the unit. So my hope was to kind of expand that to the rest of that particular jail. And then to all of the jails on Rikers Island, but I only got my seven months. So I didn’t get to do that.

Josh Hoe

Well, one of the interesting things – or not interesting, but I guess complicated or terrible would probably be the way I’d really say it – things going on right now is we actually have a national correctional officers officer shortage. Almost every state I know of is drastically short of correctional officers and most prisons, not just jails, are overcrowded and understaffed. It seems to me and you’ve kind of made a suggestion of this a little bit, that there should be a conflation of interests between the correctional officers whose lives get put more and more at risk, the more overcrowded a prison is, and the incarcerated people and advocates. It feels like we should be working together to do something about this. You know, my personal feeling is that decarceration is the natural answer, especially of [the] elderly and people on short sentences. I don’t know. Do you think there’s a possibility? I know we have, like you said there’s a lot of tension between these groups. But it really does seem like the interests right now converge in ways that should be politically interesting, at the very least.

Vincent Schiraldi

Yeah. And you know, Andy Potter’s done some good work. And has he been on DecarcerationNation? He’s a former or current president of the Michigan prison guards union.

Josh Hoe

I’ve met with him once before.

Vincent Schiraldi

Interesting guy. And, you know, he tried to help me with the guards union with the correctional officers union in Rikers, [but] it didn’t pan out. But that doesn’t mean just because it doesn’t work in one place, It can’t work elsewhere. I think there should be some room for common ground with a shortage of COs. You would think that arguments for population reduction, especially around the edges, like you just talked about, I would add technical probation and parole violations to that, lat a time when you don’t have enough staff to watch people detained on murder charges and robbery charges. You sure shouldn’t be bringing people in on missing appointments and staying out past curfew. But, but and I wonder if there is some room to have that conversation, but I’m not really in the advocacy community anymore, or any adult corrections community anymore, I would hope that, you know, we were on a good roll there prior to the pandemic, population was coming down, it was this notion of bipartisanship around this issue. I always wondered if that was a mile wide and an inch deep, and it seems a little that way right now. But if crime goes down again, which it’s starting to tick down in lots of cities, we might be able to get back on that road again. You know, unlike the way it was for much of my career in the 80s, and 90s. Because I mean, I’ve been in this 43 years now, unlike what it was like back then, there’s way more people interested. Now, I was the weird dad, when my kids were in high school, that worked with criminals. Now, I’m the cool dad. And those teenagers are sending me their resumes because they want a job in mass incarceration. And I say that, partly jokingly, but the young generation is way more interested in solving this problem than my generation was when we were their age. Philanthropy is way more interested in funding it, you know, we will often . . . one national foundation at the McConnell claw, the jet foundation Soros Foundation. When those folks started up, they were alone on the national scene, funding doesn’t make you smarter. But if you’re smart, funding sure does help you be able to get your message out. So I think there’s a lot of good stuff going on. But we’re still you know, we’re not done with mass incarceration. We’re not done with mass supervision.

Josh Hoe

So you talked a little earlier about your discussion with Mayor Bloomberg. And coming up with this hypothetical, What would you do if you had this situation? Well, at one point in time, that wasn’t a hypothetical, and someone was doing that. And yet, we ended up with supervision. So how did that happen? Can you share some of the story? I know it’s a whole bunch of your book, and I don’t want you to spend, you know, an hour talking about it. But can you summarize how we got to the point where, you know, for lack of a better term, “trail ‘em, nail ‘em and jail ‘em” is the norm rather than the exception.

Vincent Schiraldi

So probation and parole both started in the 1840s. probation in Boston, a shoemaker named John Augustus starts to bail people out, keep them out of the brutal House of Correction in Boston, and is wildly successful, he bails out 2000 people. A handful of them don’t complete probation successfully. He brings a bunch of his temperance movement buddies to help them and it’s a totally volunteer project. Meanwhile, over in Australia, Alexander Maconochie is running Norfolk prison. And it’s a terrible, brutal place. And he starts to encourage people to behave well and participate in programs. And if they do, he lets them out early. He calls it a ticket of leave, and they’re not out, completely free, they’re conditionally released. And again, there’s a bunch of voluntary parole officers who supervise them in a community. This is also happening simultaneously in France. France’s term for this process is the one that ends up sticking. The word “parole” is the French word for word. You give your word when you leave, that you’ll behave. And so at first, again, it’s voluntary bits and snatches. It started here in different states. New York launches it first. At Elmira Penitentiary a warden named Zebulon Brockway starts it. And for years and years it’s voluntary, it starts to get government funded, but still it’s based on these notions of rehabilitation, helping people. If you read the two leading decisions Gagnon and Morrissey about what rights people on probation and parole do and don’t have. They are replete with the word friendly. I kid you not. This is supposed to be a friendly interaction. Yeah, occasionally, someone will get imprisoned for revocation. But really, this is about not putting people in prison in jail and helping them survive. And that’s literally the basis of the two leading decisions today that were, you know, in the 1970s. Right before Martinson writes his famous paper, saying that rehabilitation doesn’t work. Nothing works when it comes to rehabilitating people, right before Richard Nixon declares a war on drugs and the prison population starts to grow every single year from 1972-2007. So, just as we’re about to launch this massive increase, eight-fold increase in the number of people in prison, five-fold increase in the number of people on probation and parole, the Supreme Court [is] saying it’s friendly. Don’t worry about those messy due process protections, cause why would you want to put the courts in between you and your friend who’s only looking through your underwear drawer to help you, not to violate and imprison you? And that just stays. If you go to a revocation hearing today, it’s called the Gagnon Hearing. It’s called the Morrissey Hearing on parole, Gagnon is probation. So this crazy pivot then occurs. And, you know, if rehabilitation is dead, at least prison wardens and prison commissioners have something to fall back on, their punishment, their incapacitation. What does probation and parole have? All we were, was supposed to be rehabilitation. And so the field pivoted, we started calling ourselves community corrections, we started wearing flak jackets, we started arming ourselves, we started increasing the number of conditions people have, whether they did or did not relate to public safety or rehabilitation. And we developed a hair trigger back to incarceration.

Josh Hoe

It really is a gigantic leap, because I remember in the book [as] I’m reading and you’re talking about this concept of the next friend, and I’m like, oh, that sounds lovely.

Vincent Schiraldi

Over and over and over they use the word friend, including Alexander Maconochie, when he invents it, he’s saying, you know, people were worried, why should you have to be supervised after you come out of prison? And they said, no, no, don’t worry. Let’s get friendly people to do it.

Josh Hoe

Yeah, you know, to keep this pattern going. How did we get from where supervision is about rehabilitation, trying to help people reenter society smoothly, to where we decided to charge people who don’t have jobs or housing criminal justice debt for the privilege of being supervised? I mean, I have been out for 10 years, a little over 10 years. And I’m still paying off my debt for two years on an ankle monitor. So, you know, there’s also that level too, right?

Vincent Schiraldi

Ah, that’s interesting. So, again, let’s go back to the 70s for a second. So at the beginning of mass incarceration, it was part and parcel of the Southern strategy, the Republicans, Richard Nixon’s Southern strategy, and Ehrlichman and Haldeman and I quote them in the book, talk about how this was absolutely a lie. This was absolutely a lie, to criminalize black people and hippies, because the silent majority was afraid. And you know, I grew up in blue collar Brooklyn, and I can tell you, my parent’s generation were afraid. They were discombobulated. Like, I remember when my brother came home from college with long hair, it freaked everybody out. Right? So, this wasn’t just on TV. This was happening in living rooms, where families were arguing over the Vietnam War and civil rights. And Nixon tapped into that. He said, If we can dog whistle, foment fear around race and poverty and crime, we’re going to peel off reliably Democratic voters from the south, from blue collar populations, and from the suburbs. And it worked like a charm. I mean, the Republicans have owned the south ever since and are battling today over suburbs and blue collar workers. So at the same time, as that’s happening, there’s also obviously, a lot of social factors going on. One of them is political, and it’s tax cuts and you know, withdrawing help from the poor. And the other is the outsourcing of blue collar jobs overseas. And these are the kinds of jobs that 18- year-old young men are kind of peaking on crime, right, could get with a high school diploma, not even a high school diploma that could help them start families and start to occupy adult roles. So when I went, I grew up in a blue collar neighborhood in Brooklyn with three factories on my block. And when I went to college, a whole bunch of my buddies got jobs in those factories. And by the time I graduated from college, they had apartments, they owned cars, they were starting families. And, you know, I was just starting out. That went away. That’s obviously not true [now]. Nobody could live in my neighborhood, Greenpoint, Brooklyn, for the amount of money that you could earn with a high school diploma.

Josh Hoe

Yeah, the neighborhood that I used to live in, when we lived there, it was basically poor people, and now you couldn’t even get on the block unless you had a million dollars, you know, it’s crazy.

Vincent Schiraldi

That’s right, these little houses built for blue collar workers, right? The row houses, smack, smack, smack, smack smack, factory. I mean, it was like perfect [with] the bar on the corner, right? Like it was exactly what you need to make blue collar people happy and it made my neighborhood very happy. So, you know at that time that you’re a probation Commissioner, and the message is clear, I don’t really care about what you do, I just don’t want any Willy Hortons, I just don’t want you to take a chance on somebody and have them blow up on me. And then that message gets sent out to probation commissioners who in turn, send it down the chain all the way to the frontline staff, probation officers. So when I started in New York City, in 2010, I do a 19-person listening tour. And the fear was palpable in those listening tours, at first, everybody was looking at their shoes, nobody wanted to talk. And then, you know, I finally did get people talking. They were saying things like we practice fear probation here. The only time we ever hear from our central office is when we mess up. And then we are humiliated. We’re transferred from desirable locations to ones that are far for us to travel to. So if you live on Long Island, you’re going to go to the Staten Island office, if you live in the Bronx, you’re going to go to Queens, all these, these hassle ways that us bureaucracies have of letting people know how we feel about them. And so, you know, people were saying, we practice fear probation, we, most of us who are black and Latino, incarcerate mostly black and Latino people on probation, because you’ll throw us under the bus if we don’t. And that evolved, it probably was friendlier, in the early 1970s when those two Supreme Court decisions came down. And it became more and more rule-focused, surveillance-focused, managerial.

Josh Hoe

But the element of charging folks, where did that develop?

Vincent Schiraldi

Oh, I’m sorry.

Josh Hoe

No problem. That was a great story.

Vincent Schiraldi

So at this time, right, when we’re cutting taxes, and being stingier with the poor, and more punitive, we certainly don’t want to pay for it, right? We don’t raise taxes to pay for prisons and probation services. We don’t want to . . . cut schools or not fill the potholes on Main Street so that we can, you know, provide probation services. So initially, departments start to charge people under supervision. Eventually, somebody figures out well, if government agencies can charge for this, private companies ought to be able to run it as well. And so private companies start to pop up all over the south, mostly for people on misdemeanor probation, because the state will pay for state probation. But misdemeanor probation had to be paid for by the local cities and counties. So people started to go to, you know, county administrators and say, You guys are paying for the probation department. I’ll do it for free. Just dump your probation department, my company will come in, and we won’t charge you anything. In fact, we’ll kick you a little money back. And we’ll supervise all the people on probation, for a fee, what we call user fees, to the people on probation. So then what you have is you have people sometimes getting on probation, because they were already too poor to pay some traffic fine. So me and you go into court, Josh, you can pay your fine. So you walk out of court that day, I can’t pay my fine because I just lost my job. So the judge says that’s okay, we’ll put you on a payment plan. We’ll put you on probation. This private guy over here will supervise you, you have to pay this private guy. Private guy starts to add stuff on, like urine testing even though none of it had to do with me being a drug addict or alcoholic, electronic monitoring even though that wasn’t ordered. And now the fees are really stacking up. So we got this one guy that we talked about in the book, Thomas Barrett, who was a former pharmacist, got addicted to drugs, lost his job, lost his pharmacy license, lost his family, becomes an alcoholic living in a $25 apartment a month and steals a can of beer, a $2 can of beer. He goes to court, can’t pay the fine, they put him on probation, starts to rack up probation fees, late fees, they do test him for drugs, they do put him on electronic monitoring, he can’t pay for any of that, he’s selling blood to be able to pay his fees and skipping meals. Skipping meals means he gets weak. So he’s unable to sell blood. Finally, it just becomes too much. He’s about $1,000 in arrears, tells the probation folks, I can’t pay this and they jail him for a year for a $2 can of beer. No new crimes.

Josh Hoe

Wow. I mean, I’ve heard stories like that, you know, and experienced some things like that. But that one in particular, I mean, a $2 beer, and you’re years later still in the grip of the system. You mentioned this a little bit earlier. And I think it’s important to, in a way, the beating heart of all the stories on this podcast, and everything that we talk about, is one of the first things I ever talked about on the podcast is this notion that inequality and disparity are at the heart of our criminal justice system. And there’s, pretty much a full chapter just talking about that, do you want to talk a little bit about what you’re talking about there?

Vincent Schiraldi

So, you know, you think about probation and parole, their job is to make this, it’s really kind of they were invented, to mitigate the harm from corrections. And so that means that they’re invented to help people turn their lives around in ways that maybe correction systems won’t, or maybe correction systems even make them worse. They’re there to divert people from incarceration, and really to kind of curb the worst aspects of the system. And one of the worst aspects of our system is racial disparities and racism attached to the system. Instead, what we found is that they are exacerbating that. Interestingly, the disparities of probation and parole aren’t as bad as the disparities of the corrections system, it’s lower, it’s still a high disparity, it’s just lower than what you find in prison, for example. And theorists say that that is probably because for some people, it is truly an alternative. for people with, you know, lawyers with money. Middle class, people who are disproportionately white, they’re getting the Hunter Biden, or at least what some people believe, was the Hunter Biden treatment, which is, it’s actually diverting you from incarceration. But for black and brown folks, it’s more likely, and for poor folks to be an add-on. And that instead of freedom, you’re getting probation, not instead of incarceration, you’re getting it. And then once on it, people of color tend to live in communities that are much more heavily policed. And so you know, if you’re a white kid in the suburbs, you’re smoking dope in the basement. If you’re a black kid, you’re doing it on the stoop. And the cops can arrest you for that and violate you. for black people, particularly, there’s good data, if you will, on the impact of the system on them. So at its peak, one out of 12 black men in America was on probation. One out of 12 black men in America was on probation. At the same time, one in 3 black men had a felony record. So one of the standard conditions is you cannot associate with someone else with a felony record. So how are those one out of 12 going to avoid that one out of three? And I’ve been speaking a lot about this, Josh, you know, I wrote the book, but before that I was teaching classes on probation and parole. I was writing papers on it. And one panel I was on was a guy from the Fortune Society sitting next to me. And he was living in a homeless hotel at the time, a homeless shelter, even though his mother had a bedroom for him, an empty bedroom for him, but she had a felony conviction. So his PO wouldn’t let him go home. They met another guy on another panel, who married a woman with a felony conviction, no new crimes now. Right. And he was on parole, and he got locked up for a year for doing that and came out a year later and had a wedding celebration. And his PO came. He said I had to actually keep my family off of my PO, because they were so furious about it. So I mean, and I guess you know, one of the stories we talked about in the book is Kerry Lathen. The guy comes out of prison in California. He’s out for a few months. His sister, while he was locked up, got a donation of clothing from Nipsey Hussle’s Marathon clothing store. Hussle was a musician and activist who had formerly been a gang member. So Kerry is going to a funeral for a friend and he and his nephew go, they say, let’s buy a new shirt for you at the Nipsey store so you can do some business with the guy that donated you a bunch of clothes. As it turns out, he shows up, Nipsey Hussles is there, he has a big crowd around him because he’s, you know, sort of a local hero in South Central LA and a well-known musician. And at that moment somebody shoots and kills Nipsey Hussle and Kerry Lathen gets shot in the crowd alongside him and goes to LA General, you know gets operated on, is convalescing. And instead of calling up and saying hey, how you doing, his parole officer calls him up and violates him on parole, puts him in his wheelchair, takes him to LA Central Jail for associating with a known gang member Nipsey Hussle. At the same time, President Obama and Mayor Garcetti are lauding Hussle’s life. 20,000 people are filing into a stadium in Los Angeles to hear about and praise this guy’s life. This is when the country’s cameras are focused on this, that this guy gets this technical violation that only ended when there was a lot of uproar. So it’s just an incredibly common thing for kind of risk-averse [POs], some of whom are probably just doing their jobs, some of whom are mean sadistic bastards, violating people and sending them back to prison.

Josh Hoe

You mentioned in there conditions, and all of us who’ve been on supervision, one of the things that’s constantly and, well, infuriating is one way to put it, is that there doesn’t seem to be a lot of science behind the conditions at all, much in the same way that sentences are largely made up, something like sentence lengths are largely made up, it seems like a lot of these conditions have nothing to do with actual recidivism, but all of them can get you put back in prison or jail. So what’s the story with conditions? Is there any basis for you know, why we have those conditions? Or why do we use that system? Or do you even know?

Vincent Schiraldi

Yeah, it’s folklore. You know, it’s, what do you think? What do you think would work? I mean, some conditions are essentially be good, don’t engage in behaviors that are harmful, like really that general so you can drive a truck through these things. But yes, things like you can’t travel out of the county. I was on a podcast last week, which I won’t mention because you know, it’s competition. I don’t want you to be you know . .

Josh Hoe

I don’t look at anyone as competition. I try and lift everybody up.

Vincent Schiraldi

I’m kidding, it was Code Switch, right. And Gene, the interviewer, started off, telling a story about him and his cousin in Philadelphia, driving over to Camden, New Jersey, to get some sneakers at a discount sneaker store. And, and then when they came back, his cousin remembered that they were on probation and said, Oh, my goodness, I literally just violated probation, and was kind of sick to their stomach for a few days. Because they didn’t know, did the camera take my picture? Did anybody see me? Am I going to get in trouble? So, you know, we kind of made these things up over time. Yeah, I guess it makes some sense. Not to associate with bad characters. In a society with mass incarceration,does a felony conviction define that? There’s plenty of bad characters without felony convictions, plenty of good people with felony convictions.

Josh Hoe

I had a mentor who had done time. And the whole, they had gotten me through, they’d been successful, successful on the outside, they’d come back free, integrated, all that stuff. And they helped me basically get through all the prison, I could write them back and forth when I was in prison. But the minute I got out, I couldn’t write. The person who literally got me through it is doing really well, on the outside, they can’t talk to me at all.

Vincent Schiraldi

How about the guy’s wife or the guy’s mother, like you can’t, you can’t go to see your mother. So you know, one guy, I’ll give you another story. There was a nonprofit in San Fran. I mean, I’m sorry, in New York City, that their job was to get people jobs when it came out of prison. They had all sorts of contracts and foundation money. And they did a random control trial for people who got their service and didn’t get their service to see whether it made a difference. And they were successful in getting people jobs and those people retaining those jobs and it reduced recidivism. But the people in the control and study groups were going to prison at the same level. And the executive director there had heard me speak about technical violations and was trying to explain this to their board and wanted me to come to a board meeting to explain it to them because they really kind of weren’t believing what he was saying. And so I came, spoke and told them all about how you can actually get locked up for a whole bunch of things that aren’t real crimes. Even if you’re crime free, which is exactly what we want parole to do with you, even if you’re working, which is exactly what your nonprofit is supposed to do. So I give them this whole explanation and it was all fine. Then there’s a guy there from their nonprofit who was a client, who tells his story. His story is, he comes out of prison, this nonprofit finds him a job. It’s a good job. It’s a tech job and much better than minimum wage, but it’s at night. So it goes to his PO who referred him to this nonprofit and says, Can I do this job? PO says yes. doesn’t put it into the computer, doesn’t ask for the proper permissions, because it would take too long, and the guy wouldn’t get the job. Really, by the time he would get that permission, that job would have flown. So the PO just says, Yeah, don’t worry about it. I got you. That PO goes away. Another PO comes, that PO says okay, third PO says okay, he was on in 18 months, fourth PO comes on, they don’t even talk to him. They just go knock on his door at 7:30 at night and he’s not home, ask for a warrant. Cops pick him up. And he goes to Rikers for six weeks. By which time it takes for them to figure out this guy was actually working and he really kind of was given permission to be out at night. He said when I went in, I had a job, a car, an apartment and a girlfriend. Six weeks later it came out, all that was gone I had to start all over again.

Josh Hoe

And I think people don’t understand how much this contributes to mass incarceration. I think in the book, you say that 45% of the people entering prisons [are entering] having had their parole or probation revoked, is that the right figure?

Vincent Schiraldi

45%, and that includes for new arrests, 25% for pure technicals. That’s about three, almost $3 billion a year spent on that, but now it’s 25% of people entering the world’s largest correctional system. So it’s not 25% of Norway, it’s 25% of the United States.

Josh Hoe

One part of the book that really blew my mind was the couple of examples you gave, of where public safety got better, even despite drastically reduced or actually nonexistent, supervision. First in New York, from 1991 to 2021, the population under supervision dropped 85%. And during that same period, violent crime dropped about 76%. Do you have a theory of what happened there? Or what allowed this to happen? Or why this can’t, you know, some people might say this as correlation, but why it might be a correlation that we could take as a reason to believe that we could do this and it would be successful again?

Vincent Schiraldi

And I’m not saying that the absence of probation, the drastic reduction in probation caused that reduction in crime. All I’m saying is when probation went away, it’s almost as if no one noticed. It’s why when I interviewed with a mayor who cared deeply about crime, he was barely able to pay attention to this potential new probation Commissioner. It’s just not. It made me wonder, all of this has made me wonder how naked is the Emperor? You know, how, how little is probation and parole contributing to anything we care about? And how much is it just messing with people and locking them up for frivolous stuff? So yeah, the number of people on probation and parole plummeted. You know, the good thing about what was happening in New York City, during that time period, which is why I use it as an example, is that the city was amping up support for people under supervision. They were amping up like the Fortune Society, Osborn Association, that Center for Court Innovation of Vera Institute of Justice. New York has dozens of nonprofits who are set up to help people in lieu of confinement. And then I, you know, I talked to my colleague Mike Jacobson about this. He’s like, Vinnie, the numbers don’t match up, the number of people served by those nonprofits doesn’t equal a massive decline in the number of people incarcerated. And Mike has actually calculated how much of the decline in incarceration in New York City could be accounted for by just a decline in crime, and he says it’s 60%. But that means that 40% is not accounted for. And I truly believe that all of those nonprofits coming in, and first of all, just providing help, but second of all, advocating with leaders like myself, every time somebody wants to start a piddly little program right, [like] Common Justice. For the first couple of years, Danielle Sered served a handful of kids. But in order to do that, she had to meet with the District Attorney, she had to meet with the probation Commissioner, she had to meet with all the judges. And when she was doing that, she was selling the notion that there are better ways to respond to even violent crime than incarcerating people and putting them on probation. And you multiply that over and over and over again by all these nonprofit organizations who are in there pushing for less incarceration and more help. And it had to have an impact on the leaders. So you know, I don’t think we should reduce probation and parole and dump the money into the ocean. I think we should reinvest it in communities, whether it’s these established nonprofits or more grassroots neighborhood folks, I think that would pay big dividends. I think it would help build more informal supports, and more community cohesion, that kind of stuff. I had my neighborhood growing up in Greenpoint. There were a lot of cops around, that was free mass supervision. And my mom let me go out when I was six years old, till the lights came on, because everybody on the block was my mom. Right? What we did was we stopped doing that in the 70s. And we job that out to prisons, jails, police, probation and parole. And so what we got from that is what my colleague Bruce Western calls a thin brand of safety. We’re safe, as long as this cop is on the corner, when his shift is over, we’re in danger again. Whereas if you have a cohesive community, where people are productively occupied, where people feel hope, and feel like they are contributing to society, the way people routinely feel in middle class neighborhoods, then you have a thick brand of safety.

Josh Hoe

Yeah, and you also mentioned that in Virginia, and this sort of reminds me of Michigan a couple years ago, when COVID happened, you know, our sex offender registry went dead for two years, like nobody was for . . . a court decision came down, no one was forced to register for two years. And the sky didn’t burn. That sky didn’t fall and nothing bad happened. And yet we went right back to it. It’s like the same thing in ‘95. You say, Virginia basically just stopped doing post prison parole supervision. You cite research from James Bonta that suggests that supervision has very little safety impact. And despite all these stories, and all this history, and all the whatever, we seem, if anything, more committed to supervision than ever, you know, I mean, with the crime wave that’s happened post-COVID. With the tough-on- crime stuff happening all over the media. Why are we so committed to doubling and tripling down on what seemed to me and to anyone if you really rationally look, failed ideas? Like why are the bureaucracies created? Do you have a theory for why we remain committed to what seem like really bad ideas?

Vincent Schiraldi

Yeah, I mean, the status quo just has a power that it’s difficult to sort of overestimate. This exists, and therefore, it must be good. Somebody must have thought this through. And so now, am I going to change this thing, and then have something bad happen and look like I’m soft on crime? Man I lobbied when I was a probation Commissioner. And then afterwards, when I was at Columbia, for substantial rollbacks in parole and probation. When I was Commissioner of Probation, we shortened probation lengths. When I was at Columbia, we got the Less is More Act passed, with a bunch of really great community advocates, which drastically reduced technical violations to prison and shortened parole terms. And, and so that meant I had to have conversations with elected officials. And it was super clear that the 15 minutes I had for those conversations were the first and last time in over a decade that they would have ever talked about protection. So they just weren’t, they weren’t really thinking about it. They weren’t interested in it. And to the degree that we’re concerned about what I was talking about is, can I be perceived as soft on crime if this goes away, so you know, Willie Horton fear of that one person who does a bad thing, even though you’re saving 1000s of people from being treated unfairly, and hundreds of millions of dollars on [legal] lobbying. At Less is More we calculated that it was over $600 million a year being spent on parole violations in New York, and New York had more parole violations, than any other, more people incarcerated for parole violations than any other state. And so what we’re saying is stop doing this. There’s no connection to public safety, capture the savings, then put them into job programs and, and treatment, and housing and education, things that could actually help a guy or gal coming out of prison. And so they did pass Less is More, the governor signed it two years ago, when I was Commissioner at Rikers. And it was fantastic. Hundreds of people were immediately let

out, because they had already exceeded the amount of time you could get, the maximum amount of time that you could get as a violation under Less is More. And unfortunately, that was 30 days, right? And one man, Ibraham Kareem, had been there 29 days when the governor signed, Less is More. And so he didn’t get released, as he . . . . 30 days. Next day, he caught COVID, the day after that he died. So there’s some real ramifications, big and small, deprivation of liberty, the terrible things that happen to people in prison, and just a feeling that you’re constantly under the thumb of the government you know, over and over and over again, I’ve heard that from people under supervision. It’s intangible, and I don’t think it’s a government good. I think it’s a harmful aspect of government to have people unnecessarily controlled the way we do through mass supervision.

Josh Hoe

And I seem to remember there was – and it may still be ongoing – another experiment, a new experiment in New York where they essentially got rid of officers and just had people check in at kiosks and that had, just that had better impact than the traditional form. Am I wrong about that?

Vincent Schiraldi

It’s pretty amazing. Like every way you look at this. Mike Jacobson, when he was Commissioner of Probation under Giuliani, started these kiosks, right? I mean, he said there’s these low risk people, they sit in the office two and a half hours, they get in trouble at work, let’s just have them stick their hands in this computer. It looks like a, you know, ATM, it reads their fingerprints. They answered the same stupid five questions they would answer if they waited two and a half hours to see a PO. And they go. Then Marty Horn who was in his career, Secretary of Corrections for Pennsylvania, Executive Director of Parole for New York, Corrections Commissioner for New York, and Probation Commissioner for New York, when he took over, he saw the outcomes of this, expanded dramatically, so that more than half of people are answering to a kiosk, and had Jim Austin study it. And it showed that the people answering to a kiosk did statistically significantly better in terms of recidivism, and in terms of failing to appear than people who are answering to a person. I don’t think it’s because the person made them worse. I think it’s because of the frustration of waiting for all that time. And if you’re low risk, and you’re sitting in a waiting room with guys that are high risk, maybe you’re learning some stuff you shouldn’t learn. I don’t know exactly why it was, but it did better. Similarly, on the other end, every state allows intensive supervision, probation and parole, we’re going to put you on a caseload with small case loads and you know, with a PO with small case loads, and they’re going to supervise you more closely because you’re high risk. What the research on that shows again, very good randomized clinical studies show that people on mre supervision do worse. They recidivate more, get re-arrested more frequently, and they get technically violated more than people on regular supervision. So more supervision makes it worse. No supervision makes you almost, that makes you better. When people have abolished [supervision] for short periods of time, like Virginia did, nothing seems to happen. So Marty Horn, you know, my predecessor at probation in New York City, the guy I succeeded, actually asked once when he was in between parole and probation, you know, in his career, wrote a paper saying that we should just abolish this and just capture the money and give it to people as vouchers. You go by your own drug treatment or housing or whatever. And if you get re-arrested, we’ll treat you like anybody else who gets re-arrested. And he was interviewed about this by the New York Times, and one of the things he said was, if I took all of the parole officers in New York out on a cruise for six months, would anybody even notice? And he answered his own question: to spend the kind of money we’re spending on parole, the answer damn well better be yes. And I don’t think the answer is yes, we, me and my colleagues did a study of all 50 states, over 40 years from 1980 to 1999. Controlled for a whole bunch of factors, crime rates, racial disparities, the political leanings of a state, and found that when we were looking at the two core functions of probation and parole, does it reduce incarceration? And does it make us safer, we found that it increases incarceration. The more people you put on probation and parole, the more people you ended up incarcerating. And that probation had no connection to public safety. Parole actually made you worse, made your state worse, the more people you had on parole, the more violent crime you had the following year. So you know, the conclusion was not just to scrap this thing all at once. The conclusion was, why don’t you experiment with dramatically reducing it, getting rid of all these technical violations, and even for some populations, just eliminating it, and using the savings to provide supports, just see how it does if what you care about is safety. And what you care about is not superfluously incarcerating people. I’m betting that by giving communities these resources, they would do a hell of a lot better than my POs did, driving into Brownsville from the suburbs.

Josh Hoe

As you probably remember, I always ask if there are any criminal justice related books that you’ve read recently that you’d like to recommend to our listeners. Do you have any recent favorite books?

Vincent Schiraldi

You know, I read both Danielle Sered’s book, and, um, oh, God, I’m blanking on her name right now. Um, Lenore Anderson’s book. I thought both of them were excellent. And I’m panicked, because you asked me this question. So I’m not remembering either of the names of those books. But I thought they were really . . .

Speaker

The Sered book is, As We Reckon or something like that. She was on the podcast to talk about it. I haven’t talked about the other book yet. But I have seen it, I probably do need to read it.

Vincent Schiraldi

Lenore’s book, it’s really interesting, because she talks about whether, are we really doing this for victims the way we claim we are? And she has lots and lots of evidence in their names, in their names. Are we really doing it in our names? Or are there other things going on here? And there’s lots of evidence that victims don’t want mindless incarceration and do want a more nuanced approach than what we generally mete out.

Josh Hoe

And is there anything else you’d like to say about your book? We’ve talked about it quite a bit. But you know, here’s your opportunity to push the book a little bit more.

Vincent Schiraldi

No, you know, it’s a hidden conversation. Part of the reason I wrote the book is because most people really aren’t there like Bloomberg. They just don’t pay that much attention to probation and parole, what’s your favorite probation movie, for example, it just doesn’t capture people’s imagination, the way prison does, and yet it really is substantially contributing to imprisonment. And I think as advocates, researchers, philanthropists, members of the media, we’d do well to pay more attention to this. And that’s what I hope my book contributes to.

Josh Hoe

I always ask the same last question. What did I mess up? What question should I have asked, but did not. It’s an opportunity for you to talk about anything really?

Vincent Schiraldi

You know more than the average bear. You got it. You nailed it. I think we’re good.

Josh Hoe

All right, man. Well, thanks so much for doing this. Again, always good to talk to you. And I really enjoyed the conversation.

Vincent Schiraldi

Same here. Thanks a lot Josh.

Josh Hoe

And now my take.

Supervision is absolutely the worst. I had a “trail ‘em, nail ‘em and jail ‘em” officer who frequently called to ask where I was, even when I literally was at a therapy appointment that she had ordered for me to attend. When she had to replace my electronic monitor, she tied it way too tight. I said so and she refused to change it saying it’s supposed to hurt, it’s punishment. Now remember, I never had a disciplinary incident of any kind in prison and never got into trouble on supervision. But I was constantly harassed. And I’m still, 10 years later, paying off the end of my supervision debt, for the privilege of wearing a monitor for two years. I was not allowed to visit my parents. I was not allowed to talk to the highly successful, successful formerly incarcerated person who had mentored me since before I was incarcerated after I was released, and all for what? We have had states that in essence shut supervision down and nothing bad happened. We need to get to the point where experience and data overwhelm bad faith, fear of crime posturing in this country. Thanks to Vinny for writing such an important and timely book. I hope you all will check it out.

As always, you can find the show notes or leave us a comment at decarcerationnation.com. If you want to support the podcast directly, you can do so from patreon.com/decarcerationnation. For those of you who prefer a one-time donation, you can now go to our website and make a one-time donation. Thanks to all of you who have joined us from Patreon or have given a donation. You can also support us in non-monetary ways by leaving a five-star review on iTunes. Or add us on Stitcher, Spotify, or from your favorite podcast app. Please be sure to add us on all your social media and share our posts across your networks. Thanks to Andrew Stein for doing our sound engineering, to Ann Espo for editing our transcripts and to Alex Mayo for help with our YouTube channel and website.

Decarceration Nation is a podcast about radically re-imagining America’s criminal justice system. If you enjoy the podcast we hope you will subscribe and leave a rating or review on iTunes. We will try to answer all honest questions or comments that are left on this site. We hope fans will help support Decarceration Nation by supporting us on Patreon.