Joshua B. Hoe talks with Jared Fishman about his book “Fire on the Levee”

Full Episode

My Guest – Jared Fishman

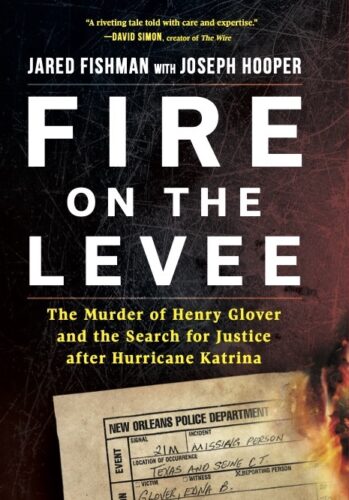

Jared Fishman worked in the Civil Rights Division of the Department of Justice for fourteen years, where he handled some of the nation’s most significant cases of police misconduct. He founded the Justice Innovation Lab, an organization that uses a data-informed approach to build a more effective and fair justice system. He is also the author of the book Fire on the Levee: The Murder of Henry Glover and the Search for Justice after Hurricane Katrina

Watch the interview with Jared Fishman on our YouTube channel

You can watch Episode 144 on our YouTube channel

Notes from Episode 144 – Fire On The Levee

The Nation article that foregrounded this entire investigation was: A.C. Thompson, Body of Evidence: Did New Orleans Have a Role in the Grizzly Death of Henry Glover, The Nation, 2018

The books Mr. Fishman recommended were:

David Peter Stroh, Systems Thinking for Social Change

Cathy O’Neill, Weapons of Math Destruction

Michelle Alexander, The New Jim Crow

The website for Mr. Fishman’s organization is www.justiceinnovationlab.org

Full Transcript

Joshua Hoe

Hello and welcome to Episode 144 of the DecarcerationNation podcast, a podcast about radically reimagining America’s criminal justice system.

I’m Josh Hoe, and among other things, I’m formerly incarcerated, a policy analyst, a criminal justice reform advocate and the author of the book, Writing Your Own Best Story: Addiction and Living Hope.

Today’s episode is my interview with Jared Fishman about his book Fire on the Levee. Jared Fishman worked in the Civil Rights Division of the US Department of Justice for 14 years where he handled some of the nation’s most significant cases of police misconduct. He founded the Justice Innovation Lab, an organization that uses a data informed approach to build a more effective and fair justice system. He is also the author of the book Fire on the Levee: The Murder of Henry Glover and the Search for Justice After Hurricane Katrina, which we will be discussing today. Welcome to the DecarcerationNation podcast Jared Fishman.

Jared Fishman

Thanks for having me on the show, Josh.

Josh Hoe

Yeah, my pleasure. I always ask the same first question, how’d you get from wherever you started in life to where you were working at the Department of Justice, and later the Justice Innovation Lab.

Jared Fishman

So I grew up in Atlanta, Georgia, I grew up in a very homogeneous Jewish community in Atlanta, and spent the first 15 years of my life really in a community that focused on social justice issues. When I went to high school – I went to a public high school in Atlanta, Georgia I had my first real exposure to lots of different perspectives. My community at school was was part black, part people from around the world, new immigrants from Latin America, from Asia, and over time I just grew really interested in trying to answer a question that was deeply instilled in me as a young kid, which is a Jewish philosophy called Tikun Olam, which says the world is broken. And we all have obligations to try to fix it. And so over the course of my career, I tried to figure out what problems I could contribute to and try to help fix. I was most interested at the beginning in war zones, I spent time in Bosnia Herzegovina, in Kosovo, in Rwanda, in the Middle East, often working with countries either coming after horrendous war, some cases genocide, where people were rebuilding. And I was always really interested in this question, what does it take to rebuild after you’ve destroyed something? And what role does law in policing and law enforcement have in it, and just during the course of my work on that one of the people I worked with in Kosovo said to me, if you care about fixing a justice system, you need to go work in the justice system first. You’re a smart kid, you’ve thought about a lot of these things, but you need to go see what’s happening on the ground, with your own eyes. And so I became a prosecutor on detail at the US Attorney’s Office in DC. And it quickly became clear to me once I started doing that job, I was doing misdemeanor domestic violence and sex crime cases, just how flawed our justice system was. How many of the people in our system were black or brown, how many of the people were going through our process and coming off way worse off than when they started. And so I wanted to keep doing this work, I wanted to keep using the power of the prosecutor’s office, because the prosecutors were the ones that had the most power to change things. And so I started working at the Civil Rights Division at the Justice Department, and I worked on enforcing America’s civil rights crimes, hate crimes, human trafficking, and police misconduct. Our office essentially were the people who were responsible for policing the police. And so over time, I would be sent out around the country, often in the wake of a police shooting, or someone who died in law enforcement or other kinds of official custody, to investigate what happened, and where we could bring criminal charges against the people involved. There, you know, I worked for 14 years as a civil rights prosecutor doing these police misconduct cases, including some very high profile ones, Henry Glover, which we’ll talk about today, Walter Scott, who was killed by a North Charleston Police officer in North Charleston, I worked on the Tamir Rice case. And I worked with a lot of people who were handling the most high-profile cases in America. And just after doing that, for so long, I came to realize that so much of the way we talk about justice in America has a flawed premise. And we’re often looking at the problems as only as if this is a problem by individuals with bad intent. And we failed to recognize how much our system itself is producing a lot of the negative outcomes that we care about, and people being killed in accounts of law enforcement or symptoms of that problem. And so I founded Justice Innovation Lab in 2020, to help work with communities to understand how their practice was leading to outcomes that they don’t want, including over incarceration, including debilitating fines and fees, and including unequal outcomes among their community. So we work with those decision makers to try to help them figure out what are the things that we have in our power right now to fix so that we get better outcomes for our community?

Josh Hoe

All right, so you were a prosecutor at the Civil Rights Division, as you just mentioned, we see there’s a lot of political noise going on right now about the DOJ. Is any of what seems like noise worth considering? Or are there problems with the DOJ that we should be concerned with beyond the politics?

Jared Fishman

Well, it changes over time. And I think what’s interesting is how things changed over the 14 years that I was there. I started working at the Department of Justice, in the Civil Rights Division under the Bush administration, I had also worked in the State Department under the Bush administration. And I can tell you, the State Department functioned very different as it related to the political calculations in the Justice Department . Even under the same administration, we had a lot more freedom and independence as prosecutors to investigate those cases, there were no politicians tinkering with our cases. As we moved into the Obama administration, what changed was that the leadership of the Civil Rights Division cared even more about our cases. So there tended to actually be more oversight, because the AG was very closely involved, Eric Holder was very closely involved. And so there became more oversight at that higher level. Now, it’s not politics and political interference. It’s just there’s a greater hand. Under the Trump administration, it sort of went at the beginning as not having a whole lot of involvement either. But by the end of that administration, that began to shift. And you could see how people were making different decisions based on what they thought was going to happen at the political level, and what levels of approval one needs to move forward. What’s interesting about criminal cases, unlike civil cases, where the politics can force the civil servants to do something, you can’t do that in a criminal case, you can’t be forced to charge someone who – I can’t imagine that happened – that people don’t think should be charged. On the other hand, it is very easy not to charge someone because of political pressure, because you know, it won’t get approved further up the chain, or that you won’t be able to do things that you need to do.

Josh Hoe

A great deal of the movement toward criminal justice reform kind of started with pushback and criticism of prosecutors. You also throughout the book, as we’ll get to in a second, seem somewhat conflicted at times about the enterprise of prosecution. where have you ultimately landed on your experiences or with your experience?

Jared Fishman

I realized that personally, it’s not the role for me, I certainly am not a person who sees a whole lot of value. What I do think is there is a role that our court system and our criminal legal system plays in maintaining order and keeping the community stable. The problem is we have been using it in a totally ineffective and abusive way for the last, like forever. And so I think there is a role that it plays, I think a lot of times those resources have been misspent. And I think what we really need are alternatives to that new system. I don’t think we’re getting rid of our current system overnight. And so I’m a big believer that there’s a lot that we can do right now. And so we have an obligation to do it right now. There is so much low hanging fruit in terms of reform, and there’s so much ability of local jurisdictions to change their practice. Because I think a lot of the discussion at the high level when we’re talking about federal laws, and what are we going to do here, like number one, I don’t think we’re in a political moment, where that’s going to be the solution. Number two, because justice systems are run primarily at the county or city level, that’s where the innovation is going to come from. And that’s where we’re going to break the mold and come up with what this nation is starving for: new ideas about how we can undercut the things that lead to the violence in our communities that people care about, that can allow people to actually grow, have stable jobs and have stable housing. And we know that many of the things that are bringing people into the system like mental health and addiction, the criminal legal system is the worst place to solve those problems. And so figuring out how do we get the people who need some assistance out of the criminal legal system, into the alternatives that can address some of those underlying conditions.

Josh Hoe

So, you’re a prosecutor in the Department of Justice, Civil Rights Division, and somehow you come across the case of Henry Glover in New Orleans. How did this come to your attention? And how did it go from a folder on your desk to an active investigation with the full power of the federal government behind it? And you know, being asked to get on a plane to Louisiana, etc?

Jared Fishman

Yeah, at the time, I was spending a lot of time looking at prison cases, cases of abuse inside correctional facilities, either at the state level or county level, in jails around the US and I had done a lot of those cases, and I was ready to work on a police case. And so I had been talking to different people in the offices and then said, I am interested in trying to take on something that’s different. And one day The Nation put out an article written by AC Thompson that suggested that this man named Henry Glover, whose body was found burned in a car after Hurricane Katrina, there had possibly been police involvement. My supervisor at the time was investigating other cases of police misconduct by the New Orleans police in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, including the Danziger Bridge shooting. And she met with the journalist and said, You know, I think there might be something to this, go look into it. Around the same time, William Tanner, who was a man who tried to get Henry Glover help, had reported this case to the FBI, they had opened a parallel case. And I got teamed up with Ashley Johnson, who is a young rookie FBI agent in New Orleans. And together, we partnered to try to see whether or not there was anything to the allegations raised by AC Thompson’s article.

Josh Hoe

Obviously, the backdrop of the entire story is Hurricane Katrina. Can you talk about walking in as an investigator to New Orleans after the devastation of the hurricane?

Jared Fishman

So I started going down in 2009, which was about three and a half years after. It was in many ways recovered. So people were living there, the economy was coming back, there was some tourism. But there were a lot of empty storefronts, there were a lot of homes that were not rebuilt, you could drive around the city and still see the marks that had been left behind from the storm. The quintessential symbol in my mind of Hurricane Katrina is this big X with a circle around it, that tells about how many bodies had been found inside this thing. And who was the agency that found them. And so you would see it, it was ubiquitous in pictures after that storm, and every time you see it, you’re like, oh, there were two people dead. And the New Orleans Police Department found them or ICE found them or ATF found them. And so they were still there, three and a half years [later]. On the other hand, It was clear by that point that people were going to return to New Orleans. It wasn’t clear whether or not they would return at the same rate, what was going to happen and what the future looked like. But people were coming back and we knew New Orleans had a future whereas previously, that wasn’t always obvious.

Josh Hoe

And can you kind of explain the basics of the Glover case as briefly as possible? It’s a pretty complicated case. And it’s a pretty long book, but just so we can get an idea of what we’re talking about.

Jared Fishman

What happened after Hurricane Katrina hit New Orleans – a lot of people think of it as a natural disaster – but it was also a manmade disaster of epic proportions. The protective levees that surround the city collapsed, and 80% of the city flooded. Henry Glover lived in the part that did not flood and so in many ways, his experience is a little atypical of some of what we think of as Katrina. But even four days after the storm he had stayed behind. He thought he had borne out the worst of it. But as it became clear that other resources weren’t returning to the city, it came time for him to leave. As he was leaving, he took a truck in order to get him and his family out of the city. He is shot behind a strip mall by [someone] who turns out to be in the New Orleans Police Department. His brother and brother-in-law are trying to get him help. They then go to the place where they think they can get help. The nearest place is an elementary school that’s been taken over by the police. The driver of that car, William Tanner, thinks that he’s going to be able to find medical supplies for Henry Glover. Instead, they’re taken out of the car. They’re beaten by the police, [with] Henry Glover in the car [it is] ultimately driven off and burned behind a levee nearby. And for about three and a half years, no one knew what happened. And so when I came in, I knew very few details. I knew that Henry Glover’s body had been burned. I knew he had [last been] in the custody of the Police Department. And our goal was to try to figure out, could possibly the police had been involved in the shooting of Henry Glover? And could Henry Glover have possibly also been burned by the police department? And what were the connection of those [things]?

Josh Hoe

So there you are in Louisiana, an outsider in a place where that matters. With a case going after, you know, a legendarily corrupt police department at a time when the city of New Orleans police were dealing with total meltdown and dystopia. How do you even start a meaningful investigation in that place under those conditions?

Jared Fishman

I mean, when you say it like that, it sounds nuts, what we did.

Josh Hoe

That’s . . . . When I started reading it, I’m like, Well, this is an interesting time to do an investigation.

Jared Fishman

Yeah, I mean, for me, for me, it actually allowed me to answer some of those questions that had really plagued me in my war zone career, which is how do you rebuild after destruction? And how do you hold people accountable after destruction, number one, and/or can you? and number two, what actually happened? Because we had to start by finding out anything that people knew. Typically when you investigate the police department, there’s an inordinate amount of documentation and we’ll start by getting every piece of paper that was written on a case, the incident reports, the radio log, you know, body worn camera these days, and we can download all of those things now and figure out okay, who was there, what happened, oftentimes there’s citizen camera or video from from other angles like banks, we can figure this stuff out. Now back then that wasn’t, none of that happened. The police weren’t writing reports regularly, there was no recording of radio [calls] dispatch wasn’t working like it normally would. And so we had to do it the old fashioned way, which was to find people who were willing to talk with us, and over time we found that I mean, in some ways, we were looking for clues, we had to first start by figuring out who was there. And so one thing that we could figure out was we knew who got paid during that time period. And who from which division got paid to do what? And so at least we began to narrow it down. Alright, this is the possible universe of witnesses, we need to start talking to people, let’s try to figure out who are the most likely people to know something? And who are the most likely people who know something who will actually tell us about it?

Josh Hoe

When you read through the book, at least the actors in this police department, a lot of them are actively working against you. Getting to this information, how did you get people to talk to you in a place where, like I said, you’re an outsider? You know, in Louisiana, that does mean something, and you’re investigating the police, and you’re trying to talk to the police.

Jared Fishman

I give a huge amount of credit to a special agent, Ashley Johnson, I think, what was really unusual, just to be totally clear, Ashley Johnson was a rookie Black woman at the FBI. She is unlike very many agents that I ever worked with. And I am a white guy, I was also a rookie at the time coming in from Justice – [total outs]. What was interesting is I think that outsiderness helped us, because on the one hand, people didn’t mistrust us, or at least some people were willing to mistrust us less than they would have the NOPD investigation that was happening at the same time. I mean, at the same time, New Orleans Police Department is also investigating this, which was incredibly unusual, in part because nothing had happened in three and a half years, the New Orleans Police Department never interviewed, never investigated this, at least not in a way that they ever admitted to, or provided documentation to support, but they started their investigation at the same time that we were starting. And so I think there were people who began to realize, okay, someone actually might do something about this, this time, those people are less corruptible, particularly for a number of key witnesses who were all young black women. They, and some older black women, had a lot of faith in Ashley Johnson. As an FBI agent, I think they saw someone who, they saw themselves in her and they were a little bit more willing to confide in her than they would have to just me or some other people. And over time, we gained credibility from people who had seen stuff that was wrong. They knew it was wrong at the time, but they never felt like they had a way to get justice or to speak their mind. And what Ashley and I tried to do is create an environment where at least some people felt comfortable coming to us – don’t get me wrong, we got lied to way more than people who told us the truth. And ultimately, you can . . . And there’s still a lot we don’t know as a result. But we were able to bring more people in to begin to unravel this secret that had stood hidden for so long.

Josh Hoe

So there was also another problem, this persistent claim that isn’t entirely untrue, made by law enforcement and others, that Katrina was just different, that the situation was such that expecting normal behavior or normal protocol, or even following the rules, to some extent, was so off the board, that you can’t even consider it. And you know, I mean, to me, an outsider who wasn’t there, I think you want to have the rules hold the most in those situations. But it seemed all the way through that this was a yeah, almost like a through line through the entire book. How did you approach this and get around that notion?

Jared Fishman

Well, I mean, that’s one of the problems with our justice system as a solution to satellite societal problems. I mean, we can speak about it in this particular context. But I think this is also true whether or not we’re talking about the mental health crisis in America or addiction crisis, it’s not a very good tool, because at the end of the day, what we can do is we can hold people accountable in a very particular way, which is by sending them to prison. And if what we really care about is having a police force that acts justly, if we really care about using our most punitive apparatus as a society as little as possible, because what we’re hoping to have is a better outcome – that’s what we want. But so I was torn throughout this whole event. I think what made it easier was no one was coming clean. And so really, in some ways, our mission number one was just figure out what happened. Because again, when Ashley and I started our investigation, we did not know it was a police officer who shot Henry. We didn’t know; we heard rumors that it could have been, the family suspected that it could have been, because there was a police substation in the area where he was shot. But it wasn’t certain that that was true. And while there was a lot of speculation that the police may have burned Henry Glover’s body, again, we had the names of no witnesses. And again, it was speculation because no one had seen the car burned. So part of it was just even trying to get our head around what happened. A lot of times when we look at police misconduct cases, it’s usually pretty clear what happened and the question is whether or not that person acted with criminal intent. What was happening here was we had to first even figure out [were the police involved at all]?

Josh Hoe

This is a complicated question and might take a while to unpack, but you did this investigation for a pretty decent amount of time. What did you uncover, at least to the extent that you could figure it out? What happened to Henry Glover in Louisiana, after Katrina?

Jared Fishman

Henry Glover and his family had stayed for four days. They thought they had ridden out the worst of the storm, but they eventually decided they needed to leave, that city wasn’t coming. Henry comes from a lower income family. There were 10 or 11 people in that family that were all trying to evacuate. They didn’t know how, they were out of town. They only had one Ford Accord car between them. So Henry Glover took a truck from a nearby firestation. He’s trying to evacuate his family and another family member had taken some things from a strip mall and said, Hey, we couldn’t carry it. But can you go pick it up in the truck now that you have it? Henry goes back, he’s trying to help evacuate his family and unbeknownst to him and unbeknownst to the person he was with, the police, a man named David Warren and his partner, a woman named Linda Howard, are stationed on the second floor of the strip mall. As Henry is trying to get this, a warning is given. Henry begins to run away and David Warren shoots Henry Glover in the back with his personally-owned sniper rifle, a gun that was aimed to shoot at distances of hundreds of yards and a gun that really has no purpose in American policing. Henry Glover falls to the ground and collapses. He’s with his friend Bernard Callaway, who immediately tries to get some help. Eventually, three men tried to get Henry Glover help and they take him to the school where they were beaten. Ultimately a jury did not convict any officers of the beating. But there’s very strong evidence that the men were assaulted while they were at [that school] during that time period, which was hard to estimate but probably about two hours. a police officer drove off with William Tanner’s car with Henry Glover still inside it. They went nearby, about a quarter mile away, to the levee. And an officer named Greg McCray burned the car with Henry Glover’s body in it. And he was also with a lieutenant named Dwayne Scheuermann. After that, pretty much nothing happened for many years. There was a missing persons report filed about three months later, there was a false police report written about three months later, or four months later. And after that, nothing happened until the AC Thompson article came out. And as we began to investigate, we found okay, not only was there this cover up back in 2005, but now that people are looking again, there’s an active cover up in 2009. And so our goal was to put together the best case we could. We ultimately indicted five police officers for their involvement at various different stages in this process, and went to trial against those five officers.

Josh Hoe

And so to do that, you start out taking the case to a grand jury. And unlike normal, had to take the grand jury more seriously. I think the joke you said in the book was that police are even harder for a grand jury to indict than a ham sandwich or something like that. What is your take on why it’s – at least in the court process – virtually impossible to hold police accountable, despite the amount of massive power that we cede to them?

Jared Fishman

Because the systems aren’t set up for that to happen there. There are incentive structures and knee jerk reactions for people to protect that. There are levels of protection that exist within the apparatus that usually tries to hold police accountable, whether that’s internal affairs, whether that’s the local prosecutor. What’s different about when the DOJ comes in is we don’t have any political attachment; we’re outsiders [and it] is a huge, huge advantage. On the other hand, it means we don’t actually know the nature of all the relationships that exist, we don’t know who’s friends with whom, who’s gonna have information on who. So a big part of starting an investigation is figuring that out. What the grand jury allows you to do is to bring people in under oath. So it enables you to use that testimony in the future if you need to. Because a lot of times you might get the truth now. But when we’re in trial in two years, that person’s not going to say the same thing. The pressure is more real when they’re out in the public eye. And part of what the grand jury can do is number one, to secure testimony to try to piece together what happened in an environment that is decidedly usually unwilling to tell you what happened. As a result, it takes a lot longer, and it takes a lot more resources. And a lot of local

DAs offices are just not either able or willing to put those kinds of resources in, and there just aren’t enough federal resources. they’re super labor intensive.

Josh Hoe

You also decided to try multiple defendants at the same trial. I think most of us who’ve been following the news lately know that the Georgia prosecutor was trying to do something similar in her prosecution of Donald Trump and his menagerie of co-defendants. What led you to this decision and what challenges did it create to have multiple defendants in the same case? What are the benefits?

Jared Fishman

Yeah, I mean, you’re trying to tell a coherent story from A to B, and the rules of evidence sometimes restrict whether or not you can tell a coherent story. And I think that was particularly true in this particular case, because there were people involved at different elements of the case. What happened at the shooting involves different people than what happened at Haven School, which then involved different people later on. But the story is still linear, one thing led to the next thing led to the next thing. So if you’re trying, if you think of trials as a story, because what we’re trying to say is, hey, jurors, this is what we think happened based on everything we know. And we’re asking you to hold these people accountable for what they did, but because different people are involved, there’s different protections, and nobody gets the protections better than police officers, every protection that our constitution offers, they get. In jury selection, they get it in motions in limine, they get it with character evidence. And so you have to try to be able to tell a story in a way that overcomes those things and is compelling to the people who are listening. And so for us, we knew that it was the same witnesses that told us about the shooting, that also talked about some stuff that happened at the school, who could also tell us some things about the cover up, that happened. And so we needed to be able to have them tell their full stories in one setting so that this thing that doesn’t make any sense begins to make sense.

Josh Hoe

And then we know that in general, only like 4% of cases go to trial. In most cases, there’s a plea bargaining process. I know, that’s probably not the case at the Civil Rights Division. But what are the differences in process that meant that this case went to trial? I mean, were you also trying to roll up the other folks and get them to testify against others? Was there the normal process where you offered plea bargains? Is that even a thing in Civil Rights Division cases? How did this differ in that manner, from what most of us who’ve experienced the justice system as a defendant normally would experience?

Jared Fishman

Yeah, I think it’s very different. Like you said, I think in federal cases, I think it’s 2% of cases go to trial. You know, in the state system, I think I hear five or 6%, depending on where you are. So the vast majority of these cases are going to be resolved in plea bargaining or possibly under diversion in the federal system. That is usually the case, except for in Civil Rights Division cases, particularly as it relates to the police department, I have a far greater percentage of my cases go to trial than plea out. And I think it stems from a number of things. Number one, police officers, when they go to trial, are presumed innocent, and the prosecution has to prove those cases beyond a reasonable doubt. I know that is the standard for all cases, but it absolutely happens for police officers where it absolutely does not happen a lot of times for most people who experience the justice system. And so we have to remember, we’re operating under the same rules, but the way it actually plays out in practice, this can be quite varied. And so thinking through how do you begin to do something about it, you have to understand that police officers are gonna get every single protection.

Josh Hoe

I get asked this question a lot. Since we’re talking about the civil rights division peculiarities, it’s a good time to ask this. a lot of times I’ll be working on something and someone will say, Well, you know, couldn’t we try to get a Civil Rights Division case out of this? How does that process actually work? And how does the Civil Rights Division actually pick cases?

Jared Fishman

I can’t say how it’s really working right now, because I haven’t been there for three years, but I can tell you where it was then and where things have changed. When I first started, it would be really hard to get a case . . . I think with the increased prevalence of videos we’re seeing, that is the thing that more often than not, is driving involvement. And, the way cases were getting to us in later years was coming increasingly through media, increasingly because there was video. And, and it is almost to the detriment of the cases that didn’t have

. You know, the Glover case, if the Glover case came in the door today, and someone’s like, Well, is there any video and they’re like, No, there’s absolutely no video? Well, who are the witnesses? No idea. But we know this man was burned behind the levee. I’m fairly certain they would not send a similarly situated Jared Fishman character down today, because it would be like that’s way too much of a long shot. Now, it’s going to be driven by, usually it’s by reporting and by videos. The other day I read an article and I was like, Hey, you who run the states involved in this case? Are you aware of this thing? And then a few days later, I read that there was a new case being . . . so I think a lot of it is getting into someone in that jurisdiction. It could be the FBI, it could be the US Attorney’s Office, it could be the media, and usually when there’s an allegation, you’re like, Okay, there’s maybe something to this and it comes down to What resources are available at that time? And who’s going to staff it? I think there’s an increased likelihood that things get staffed when people are like, Yeah, this is a very obvious wrong. What I think is challenging a lot of times is when you start off, it’s murkier, and finding people who are willing to put the time and the resources and the motivation into it, have to believe that there’s something [there].

Josh Hoe

I think one of the things that I love the most about this book, and it’s in a way, and in the story, is that the whole power and, or at least as represented by a Jared Fishman-like character of the federal government, was unleashed in defense of one person in New Orleans, during Katrina. I mean, it just seems astounding to me that, you know, that could happen, you know, it almost defies cynicism to some level. Was it your experience that that was even a remotely normal practice? Is that a normal way? I mean, are there people all over the country who are experiencing the way the civil rights division works in that manner? Is that fair to ask?

Jared Fishman

Yeah, I mean, the the people in the Civil Rights Division, I think there’s like 50-60, attorneys at any given time, they are out in the field responding to these allegations, all the time, when there’s an allegation of a rape inside a prison, like, it’s oftentimes the people in my office who go, when when there’s a police shooting of looks really suspicious, it’s the people in my office who go, and so those people are, on the road for years, we were on the road all the time. I spent, over the course of my 14 years, I think I was in 30 different jurisdictions. So you spend a lot of time on the road, always an outsider dropping in to try to figure out what happened. And that takes a lot of work. And where it works best is when we drop in where we have really good partners on the ground, whether that is local investigators. So I’ve worked with the FBI, I’ve worked with Ally GS, I’ve worked with state police, it can really vary from place to place. And so you, you try to build those relationships, the best you can get to the bottom. And sometimes those relationships never come together. And you don’t have an adequate partnership between the lawyers and the investigator, those cases are usually going nowhere. Where it works out is where there are people from these different parts of the system who want to do something about and care enough to do something. The sad part is, yeah, it is driven by this system problem. But it’s also an individual problem, we need people who are inside systems making better decisions, we need people who care about unearthing these harms because they see it as harms against us as a society, as harms against as a community. And also realize it has serious public safety implications when communities do not trust their police department. And if we’re ever going to get out of this, we have to have communities and police departments that are willing to work together and trust each other in many places. That has not happened for a very long time.

Josh Hoe

And so, you know, you enter into the trial. We see trials so rarely, as we talked about a second ago, that it’s almost like I think people kind of have the idea of trials that happen on TV or in the movies. But it seems like at least as I was reading the book, that this was a fairly lengthy process. And that had a lot of stress on you, a lot of stress on the different, you know, trying to get witnesses at the right time, trying to find people, stress on your partner, your life partner, stress on the court itself. How long did the process take? And what were some of the struggles?

Jared Fishman

Depends how you count. You know, our investigation lasted about [9-18] months. And so in some ways, that was a phase where I was jumping into New Orleans for two or three days at a time over some weeks. I was there back to back weeks, sometimes I wouldn’t go down for three weeks. All the while Ashley and her team at the FBI are always on the ground, as well as Tracy Knight and Laura Orth at the US Attorney’s office that I worked with, they were on the ground moving things along all the time too. Then you go to trial. Our trial was a four week trial. And you know, we rarely actually talk about the logistical hurdles that you just mentioned, right? We call 30-something witnesses; our witness list was even longer than that, where we have to be constantly in contact with people because we’re also in front of a judge who’s like, you’re gonna have six witnesses in court tomorrow. So on the one hand, you want to tell a compelling story in an order that’s going to move the jury to do the thing we want, which is to hold these officers accountable. On the other hand, I got to make sure that I can get them to court in that order, and that they’re ready to go and that they’re ready for cross examination, and that I actually know what they’re going to say and that we have all of the pieces of evidence that we need to do. And so it’s incredibly logistically complicated. Laura Orth, who was the head of the legal assistants, Gina Yeoman, who was the paralegal in our office, did a remarkable job keeping that going, as well as we had a great victim witness staff. I think one of the things to remember is to do this right, in any case, you need those resources. And way too often people don’t have those resources, which means that we’re not supportive to the victims and getting them services, that we’re not finding witnesses who are crucial to tell some stories. And so you’ve got, you’ve got police officers who are getting all of these various protections and are willing to put you to the test to prove it beyond a reasonable doubt. And so it just makes it that much harder. So once we started the trial, it was four straight weeks. I think I was gone from my family, probably for six weeks while my wife was at home with our newborn trying to run her own business, while also raising our child. We’re working ridiculous hours every day, this judge had us in court, usually at 7:30 in the morning, every day. We often didn’t leave the courthouse until 5:30 every day, and then we’d still have another few hours of work. So it was definitely one of the most intense work periods, with very little sleep, trying to do this thing that is emotionally challenging, all the while knowing that your jury is inclined to give the defendants the benefit of the doubt.

Josh Hoe

And speaking of that, how did the trial end up? Were you able to get a good result for Henry Glover and his family?

Jared Fishman

Well, I don’t want to be too specific. Because I want people to read the book. It turns out differently for different officers, and people who had different roles. And I think people’s approval or disapproval of the outcomes kind of depends on which officer we’re talking about and what they think about it. I think the criminal legal system showed that it is wholly inadequate to judge a case of this nature, and to judge problems that we’re talking about, that are facing our legal system and policing in America. If we’re really going to solve those problems, it’s going to take a lot more than any given criminal trial. And so what I hope in the story, and why I wrote it is so people can understand why it’s so hard. What are the different systems at play in reading the outcomes that we’re seeing? And what do we want and expect from our police departments so that we can have a smarter conversation about what’s going to happen next? One of the things that happened in New Orleans as a result of this case, as a result of the Danziger Bridge prosecution, as a result of other problems, prosecutions of police officers, is that New Orleans entered a consent decree to radically remake these departments. And while it certainly hasn’t been a complete success, there have been remarkable improvements. What the New Orleans Police Department have today is a way better department than it was when I started, [there is a lot of work]. And so part of the continued move to move forward is we absolutely have to hold people accountable when they do things that are wrong. On the other hand, we also have a lot more work to do that can change the way this happens in America. Every year, over 1000 people are killed in interactions with the police. 1000 people every year – [it] hasn’t changed for the last, I don’t know, 5-10 years, however long they’ve been keeping track. We don’t even know exactly how many people are killed by the police every year, because there’s no standardized way to collect it. The people who’ve got the best numbers [are] Washington, DC, they’re the best. I mean, hands down. They’re the people with the best numbers in America on police shootings. I think they’re probably drastically under-counting would be my guess. I don’t know by how much. But my guess is they’re missing a number of those shootings. And so how can this happen, that every year this is happening, and we’re not being more thoughtful about it? How do we stop it? How do we ensure that that our police and our communities interactions are not [leading] in deaths? When you consider that most homicides in America are committed between people who know each other in some sort of way? The one number I’ve seen is that one in three stranger killings are by the police, one in three people who don’t know each other is a police involved shooting, that can’t happen. That has to be a symptom of a way bigger problem. And I think it’s going to take a lot more than just prosecuting police officers to change that number. It’s gonna take communities who really want to understand all of these different things that are contributing to these outcomes.

Josh Hoe

One of the things that you referenced, and I think it’s constant in the book is this omnipresent idea of people experiencing and confronting trauma in people who survived the hurricane, in officers and in people who commit crimes and victims and survivors of crime. Do we need to create additional supportive systems and an architecture for dealing with trauma in this country too?

Jared Fishman

Absolutely, I mean, I think it’s one of the things that the police and prosecutors and the justice side of the house, and I think even to some extent, the public defense side of the house, has not done enough, is understanding how trauma informs . . . . It’s clear from many of the people who I’ve seen do horrible, horribly violent things to other people over the course of my career. They almost all have very deep traumas. And they manifest themselves and do violence. And so if what we actually care about is preventing violence, which in every community I’ve ever been in, people want to live in safe communities, they want to know their kids can go to school and not worry about violence, we have to begin to deal with some of this trauma. We do a terrible job at it. And I think this is true of both the police. Right, the police. One of the things that I think people on the left who are often quite critical of police and police abuse in America don’t, I think, fully appreciate is how much the trauma police officers are experiencing, is leading to things like inappropriate use of force. There is definitely a strong connection to exposure to trauma in and future use of force and other bad outcomes by the police department. And so police departments have to take that head on, communities that are experiencing violence, so much of what we see is tit for tat violence. When I first started being a prosecutor, I used to go watch homicide trials in DC because I thought to be a real prosecutor, it had to be like Law and Order, I had to go watch the murder trial so I could one day be Jack McCoy. And when I walked into those courtrooms, virtually every single time, every murder case I watched were between two young people who didn’t know how to deal with their emotions, who got into an argument where one person had a deadly weapon, and it [wound up] and someone died. Like I just saw that over and over and over again, that was not Law and Order. But that’s the reality of who’s killing people. And if we’re going to stop that, we have to figure out a way to address some of that underlying trauma. And what we do [now], our solution, is to send people to a place that is going to afflict them with more trauma. I mean, there’s a really interesting study that came out of Suffolk County that we’ve now replicated in South Carolina, looking at non prosecution of certain types of low level cases. And what it looks at is what we call the marginal defendant, who is the person entering the system that their outcome depends on who it gets assigned to, because most of the time prosecutors agree we should prosecute this case, or they agree, we should not prosecute this case, most of the time, like 80% of the time they agree. But it’s these middle cases, these 10 and 20%, where there’s disagreement, and so your outcome for the defendant depends whether or not you get the more punitive or the more lenient prosecutor, which in and of itself is incredibly problematic and unfair. So what some of these studies have looked at is what happens to them? What happens to the person who gets prosecuted? And what happens to the person who doesn’t get prosecuted? And guess what, if you get prosecuted, you’re way more likely to get re-arrested, you’re way more likely to find yourself back in the justice system than if you didn’t get prosecuted. So if our goal is to keep people out, then we need to think about what we are doing?

Josh Hoe

So you moved on from being a prosecutor and created the Justice Innovation Lab? First, what is the Justice Innovation Lab?

Jared Fishman

The Justice Innovation Lab, is a group of people from a really diverse set of skill sets; we’re data scientists, former prosecutors, we’ve got specialists in Adult Education, we’ve got communication specialists, and we go into communities that are trying to solve some criminal justice problem that’s leading to outcomes that they don’t want. And we help them understand where in their systems and where in their decision-making and where in their processes are they doing these things that are leading to bad outcomes in their community? So they can fix them. Oftentimes, it means we’re looking for the low hanging fruit, what are the things that are in everyone’s power today that we can fix today so that we stop getting bad outcomes that we don’t like? And usually that means working with prosecutors, it can mean working with the police departments, it can mean working with the courts. In Charleston, South Carolina, we were looking at things, helping them understand how do we get these cases that have insufficient [evidence] where the police are arresting people in cases that [be there]? How do we get those cases out of the system faster, so that the system stops having as many debilitating impacts on the person stuck in it, because the reality when we were helping them look through their data is that 20% of their cases were being dismissed. Because the cases just were not legally sufficient or were problematic or were overcharged. And we know that just even being in the system has incredibly debilitating effects. Or if you have to pay a bond, you know, 10% of whatever bail gets set for you. You’re never getting that money back. And people are stuck in jail, and people are losing jobs. And given the slowness of the process, this can hang over your head for hundreds of days, if not years. And so one of our goals was, how do we solve that problem? How do we get those people out of the system that everyone thinks should not be there as quickly as possible? Other projects that we’re working on are trying to help places understand where we can trigger mental health resources? We know a lot of people entering the system right now are in a mental health crisis. I had plenty of those cases as a prosecutor. And I can tell you prosecuting those people is the worst thing that we can [do]. I had a woman come to me once – this is like my very first case as a prosecutor. And it was a theft case. And it was domestic violence because it was the sister who had stolen from the brother who had severe mental health issues [and] had stolen her lawnmower. And for the longest time I was really confused. Why was this case there? Why was I handling the theft of a lawn mower? And the answer was the family really wanted to get their brother help and this was the only mechanism that was available to him to get his mental health treated. And that case went on for weeks, and the amount of resources on the criminal side that just didn’t make any sense at all, to be able to trigger some mental health stuff that we should have gotten to this guy months and months earlier, it just doesn’t make any sense. And so can we begin to build this into our process, if our goal is to end violence, if our goal is to keep people who don’t need to be in the system out of it, we’ve got to build new systems [in] most places, again, because this is all happening at the county and city level. They just haven’t done it. And so we’ll go into jurisdictions, and we’ll help them find the solution for them. And when we realize that something is really going to work, we try to figure out how . . . . sometimes it can just be as simple as, Hey, you guys stopped doing this thing. Usually, it’s more complicated because prosecutors are often elected, or popularly elected so there’s a political thing going on, there’s often really complicated different relationships, but the court and the defense and the prosecutors, it all varies in every year, every jurisdiction, the alignment is different. And so you’ve got to figure out where are these places where we can move a lever right now to reduce – what we’re trying to do is reduce so much of the harm that’s in our system right now with mechanisms that are currently in people’s control?

Josh Hoe

And who do you want to try to find the Justice Innovation Lab? And where can people do that? Where can people connect with you?

Jared Fishman

You can check out our website, www.justiceinnovationlab.org. We’re going to be upgrading it in the next week or two. So you can check it out now and then check it out in a few weeks when we have our new website up. Who am I hoping to reach? we’re actually hoping to reach a lot of different audiences, we’re looking for Prosecutors Offices who want to bring this approach inside or mayors or police departments, or anyone who’s got data and who thinks this system isn’t working. Because what we help people do is dissect their system, we help them look at their data so they can see on the whole what’s happening, because the way we use data is to try to understand what is happening most of the time. And when those things are not the things that we want. Those are the things that we should start on, because we can make the biggest difference.

Josh Hoe

You know, I think in a sense, oh, go ahead, sorry.

Jared Fishman

I was just gonna say, so in addition to the law enforcement side of the house, we’re also looking for communities, we recently, a civil rights lawyer, in a place that we’re still in negotiations with so I won’t, I won’t say who, but found us, liked our approach, connected us with people in the system who are trying to do good things. We’d like to find leaders who are trying to tackle some of these hard questions, we’re looking for communities that have mobilized enough resources that we have a chance that we can, because these are long haul engagements, they take 18-24 months before we see progress, because we need to bring the right people to the table, we need to make sure that we’re operating off of information that people think is reliable, we need to take an approach to it, where we recognize that we might be wrong. And so we should approach this work with a degree of humility. And we should see what’s happening and adjust and create feedback loops so that we can fix the things that are not working out. That’s not the way government typically works. And so we’re actually trying to bring a whole new approach to this. And then we’re also looking to find more academics and people with skills like data science, who can come on board to help us take on more jurisdictions. A lot of times one of the real values that we do is we’ll have good clean, reliable data in a jurisdiction that wants to solve a problem. And so bringing more people in to help us analyze that data and have a more thorough understanding [of] what’s happening in a community actually means that the levers that we can push in order to fix more [problems].

Josh Hoe

So what I was gonna say is that, you know, in an hour long interview with a book that, this book plays in a lot of ways, like a movie, there’s lots of characters, it’s a really interesting read with a lot of drama and a lot of different ups and downs. And you said you didn’t want to ruin the ending. So if people want to buy your book, Fire on the Levee, is there anywhere in particular you recommend that they look aside from the usual sources?

Jared Fishman

All the usual sources are available, if you want to support a local independent bookstore, I recommend doing that. Amazon, last I checked, was running a sale. So that’s probably the cheapest place to buy it right now. But I understand a lot of people don’t like to buy from Amazon. It’s widely available. And so go wherever you want to buy a book. I tried to write a story that would be compelling that would keep people going the whole time. Because these are serious issues that people often get bored of real quick. And I hoped to write in a way that shows the compelling human impact of these things. I think it’s a super interesting story that I hope readers will . . .

Josh Hoe

I always ask if there are any – speaking of books – any criminal justice related books that you like, and might recommend to our listeners; do you have any favorite books aside from your own?

Jared Fishman

Oh, man, I’ve got lots of favorite books, though I think some of the ones that have been most influential to me, might not even be criminal justice. A book that I often recommend is Systems Thinking for Social. I think for me, it’s given me a lot of . . . So I want to make sure I got that title right. Oh, that was Systems Thinking for Social Change by David Peters Stroh, I think it’s a really remarkable understanding of how we can begin to think differently about systems so that we can create the outcomes that our communities want. I’m a big fan of Weapons of Math Destruction, which has a great chapter on data in the criminal justice system, and the dangers and pitfalls that some of that happens. I think The New Jim Crow is an amazing book that helps explain how we got here. And I think, particularly in conjunction with this book, it really helps see how the problems in our history of our past are intertwined in the system. And why taking a systems approach is going to be a really good way to try to solve some of these problems.

Josh Hoe

I always ask the same last question, what did I mess up? What questions should I have asked, but did not? which is really a question so that if there were things you wanted to cover that I didn’t cover, you have an opportunity to talk about.

Jared Fishman

I mean, I guess just in closing, one of the things that I really learned in looking at our justice system, and learning how systems work is that systems are not the sum of their parts. They’re the products of their . . . . And so if we want healthy, functioning systems, it means strengthening the relationships among key players who are impacting it, regardless of where you are in the system. As someone who was formerly incarcerated, or someone who was a prosecutor, or someone who is working inside the system or outside the system, we all have an amazing amount of relationships. And we need to work those relationships, improve those relationships, so that we can begin getting better outcomes. So think about the people that you’re interacting with out there in the world and think about the ways that you can improve those relationships to get the kind of outcomes that you need in your [community].

Josh Hoe

Well, I want to thank you so much for doing this. I really enjoyed the conversation. It was really nice to get to know you a little bit.

Jared Fishman

I appreciate it! Thanks for having me on the show.

Josh Hoe

And now my take.

As much as I complain about prosecutors, it’s great that there’s a Department of Justice Civil Rights Division. There, prosecutors have helped address police officer abuse, even against one of the many human beings who lost their lives during Hurricane Katrina. I get frustrated, because I’ve seen so many of the reports that the Civil Rights Division puts out be entirely ignored, as they were in Alabama after several reports found that civil rights of incarcerated people were being violated. But it’s easy to forget that the Division has also had many impactful successes as well. I really appreciate the work Mr. Fishman did and continues to do to create a more just system. You should check out his book and look up his organization; I’ll put links to all that in the show notes.

As always, you can find the show notes or leave us a comment at decarcerationnation.com. If you want to support the podcast directly, you can do so from patreon.com/decarceration nation. For those of you who prefer a one-time donation, you can now go to our website and give a one-time donation. Thanks to all of you who have joined us from Patreon or have given a donation. You can also support us in non-monetary ways by leaving a five-star review on iTunes. Or add us on Stitcher, Spotify, or from your favorite podcast app. Please be sure to add us on all your social media and share our posts across your networks. Thanks to Andrew Stein for doing our sound engineering, to Ann Espo for editing our transcripts and to Alex Mayo for help with our YouTube channel and website.

Thanks so much for listening to the decarceration nation podcast. See you next time.

Decarceration Nation is a podcast about radically re-imagining America’s criminal justice system. If you enjoy the podcast we hope you will subscribe and leave a rating or review on iTunes. We will try to answer all honest questions or comments that are left on this site. We hope fans will help support Decarceration Nation by supporting us on Patreon.