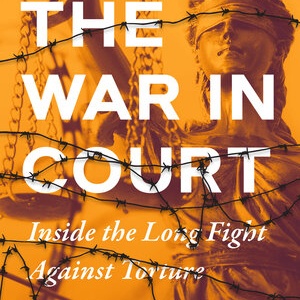

Joshua B. Hoe interviews Lisa Hajjar about her book “The War in Court: Inside the Long Fight against Torture”

Full Episode

My Guest – Lisa Hajjar

Lisa Hajjar is a Professor of Sociology at the University of California, Santa Barbara, whose work focuses on the relationship between law and conflict. Today, we are going to talk about her book “The War in Court: Inside the Long Fight Against Torture”

Watch the Interview on YouTube

Watch episode 135 of the Decarceration Nation Podcast on our YouTube channel.

Notes from Episode 135 – Lisa Hajjar

Some of the Supreme Court cases we discussed included:

You can read the John Yoo memos and many of the other documents of the Bush administration on the “Torturing Democracy” website

The Books Professor Hajjar recommended were:

Guantanamo Diary: Restored Edition, by Mohanedou Ould Salahi

Don’t Forget Us Here: Lost and Found at Guantanamo, by Mansoor Adayfi

Moving the Bar: My Life as a Radical Lawyer, by Michael Ratner

She also recommended the movie “The Mauritanian” which is currently available to stream on Paramount+

Full Transcript:

Hello and Happy Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Day. Welcome to Episode 135 and to Season 6 of the Decarceration Nation podcast, a podcast about radically reimagining America’s criminal justice system.

I’m Josh Hoe, and among other things, I’m formerly incarcerated; a freelance writer; a criminal justice reform advocate; a policy analyst; and the author of the book Writing Your Own Best Story: Addiction and Living Hope.

Today’s episode is my interview with Lisa Hajjar about her book The War in Court: Inside the Long Fight Against Torture. Lisa Hajjar is a Professor of Sociology at the University of California, Santa Barbara whose work focuses on the relationship between law and conflict. Today we’re going to talk to her about her book, The War in Court: Inside the Long Fight Against Torture. Welcome to the Decarceration Nation podcast Professor Hajjar.

Lisa Hajjar

Thank you for having me.

Josh Hoe

I always ask the same first question, the answer to which in your case could be particularly interesting. How did you get from wherever you started in life, to where you were extensively involved in researching, and even in a sense, being a kind of direct witness to our government’s involvement in extraordinary rendition and torture?

Lisa Hajjar

Well, I would say that my journey began when I was a graduate student, and I decided to do my doctoral dissertation on the Israeli military court system in the West Bank in Gaza. And so, you know, I had originally conceived of that project as looking at the way in which Israeli and Palestinian nationalisms clash in that setting, but when I got to the field to start doing fieldwork, and it was 1991, one of the things I realized very quickly was the centrality of torture, Israeli torture of Palestinians, to Israel’s larger control strategies. Because at the time it was sort of on the tail end, I was starting my work on the tail end of the First Intifada, and the way in which the Israeli government had responded to that massive uprising against protracted denial of self-determination was really escalating. There were already intense arrests, prosecution, charges in the military courts, conviction and imprisonment, and torturing people for confessions was absolutely central to that whole process. So it really gave me that fascination with the questions of torture and the law. But the other thing that really kind of positioned me well for what eventually developed after 911 into my work on US torture was the fact that Israel became the first government in the world to quote-unquote, “legalize” torture. Back in 1987, the government had decided to officially endorse what they euphemized as moderate physical pressure tactics in the questioning of Palestinians. And it was government lawyers who kind of provided the veneer for that rationalization. So one thing to say is that many governments torture, but only liberal or politically liberal governments feel the need to try and justify it by reinterpreting the law. And so after 911, in the immediate aftermath of 911, I was listening to things that US officials were saying about how they were going to respond to the terrorist attacks and how they were planning to wage this new war on terror that begins almost immediately after 911, and it became clear to me that the plan was to use violent and coercive interrogation tactics. And so it really made me, in hearing things that US officials were saying, Cheney, former Vice President Dick Cheney, most obviously, about what was going to be done to people who would be captured, I could see that the United States was planning to emulate the Israeli model. And so that was really I’d say, so I was looking for signs of US torture long before those signs became public. And that’s sort of like the seeds of the book that, 20 years later, I published.

Josh Hoe

Before we kind of get more deeply into the book … In the book, you mentioned another precursor, which was a US program called the Phoenix Program during the Vietnam conflict. I wasn’t familiar with that. I was a little more familiar with the Israeli example. Could you talk a little bit more about that program, so that everybody gets that context too? Sure.

Lisa Hajjar

In the context of the Vietnam War, the Vietnam War was the first major war that the United States was involved in in the 20th century. That was really what they call an asymmetric war, at least the government was characterizing it as an asymmetric war, meaning that the US military was fighting against unconventional enemies. I mean, the North Vietnamese were obviously a conventional enemy, but it was the Viet Cong supporters of a unified Vietnam and supporters of, you know, Ho Chi Minh in North Vietnam in the south, who were sort of engaged in the war as unconventional fighters, not wearing uniforms, etc. And so one of the programs, the Phoenix Program was developed in order to do what often happens in asymmetric wars, where a government needs to gather what they call human intelligence, like the intelligence from human beings about things that are not otherwise detectable. So when you’re fighting with an unconventional enemy, there’s not massive troop mobilization or things that can be spotted through aerial surveillance, it really depends on interrogating people for information. And so the Phoenix Program was basically run by the CIA, with sort of the collusion of South Vietnamese police, and it involved capturing people and brutally interrogating them for information about Viet Cong activities in the south. And oftentimes, people would just basically be tortured, so brutally, and then when the interrogations were done they would be killed. So they were then extrajudicially executed. So about 27,000 people were killed as a result of the Phoenix Program. But as often is the case when a government is relying on torture for information, it doesn’t actually work. It’s an idiotic presumption. And, you know, as we all know, the United States lost the Vietnam War. So that was, it’s a very dark stain. But it was, was a precursor, because someone like Cheney, who really comes of political age in the 60s and 70s, and was very hostile to the kind of post-Vietnam reforms that were instituted to prevent things not only like the Phoenix Program but also like COINTELPRO, where the FBI would spy on anti-war activists and civil rights leaders and so on. Cheney was very hostile to those kinds of efforts to rein in the state. And so what happens after 911 really provided an opportunity for Cheney and a small circle of lawyers around him to really reboot the power of the executive branch to shut off the kind of oversight mechanisms that had been instituted in the 1970s and 80s. And bring the United States back to where the executive branch could operate without much oversight and at its own discretion.

Josh Hoe

And you talk about Cheney, so we’re attacked on 911. And the administration, particularly Cheney, decided that the war on terror should be a different kind of moral one in which we heavily invest in arrests, detentions, rendition, torture, or I guess what they would call it, enhanced interrogation. What do you think caused the shift in their minds? Or is it just something that Cheney was always committed to? Do you think there was anything that created this kind of shift?

Lisa Hajjar

Ignorance, Cheney was ignorant? I mean they, he and the people around him, that sort of echo chamber, knew nothing about what actual effective interrogation involves, and effective interrogation does not involve torture and violence, but they had deluded themselves or persuaded themselves into thinking that these nefarious enemies, Al-Qaeda and others, who were the unknown enemies. I mean, that’s also part of the issue, that when the United States began the war on terror, they didn’t actually know who they were fighting or what they were looking for. But there was this hubristic assumption that violence would work and that anybody that we caught and put into interrogation in Bagram or then soon thereafter, shipped off to Guantanamo must be a terrorist. And the only way we could get information from them must be through degradation and violence. And then, you know, the logical assumption of that kind of ignorant posturing is that anything they would say would then become true. And when you’re using torture, you don’t actually know if a government needs to rely on torture, they don’t actually know what the answer is. So when you torture people for information, there’s no way to judge whether what is being said is true or false. Whether people are saying things just you know, sort of following back on the kinds of questions they’re asked and telling their interrogators what they think those interrogators want to hear, just to make the violence and the pain stop. So, you know, the whole origin of the War on Terror was basically hubristic ignorance. And that’s what really drove the torture policy. And I would also add that in order to make a government policy based on ignorance and hubris, they have to actually cut out all the experts, and that was something Cheney was very comfortable doing, was excluding military lawyers from the discussion of military interrogations, and so on. So it was a witch’s brew of horrors.

Josh Hoe

Unfortunately, that’s been somewhat of a precedent that’s been followed in future administrations. So when we talk about torture or enhanced interrogation techniques, what was included under the …. of enhanced techniques, at least post 911?

Lisa Hajjar

Okay, so the strategy that people, once they decided they were going to engage in violent intent or authorized violent interrogation tactics, what specifically happened, like the real kind of framework for what was developed first by the CIA, and then spread to the military – just to provide a little bit of context – we’ll see if we can go back to the Korean War, you know, for this context. So during the Korean War, one of the things that happened was the shocking speed at which American soldiers who were captured by North Korea or China were basically broken, but they would make false statements, and so on. And so after the war, the military did, you know, sort of really did, a study of these former American POWs to understand both what had been done to them and why they had broken so quickly. And so the mechanisms that the Chinese used were not really physical beatings, it was, you know, different kinds of ways of really attacking, attacking the psyche of people. So, stress, I mean, it wasn’t unphysical there were physical aspects, but it would be, you know, degradation, protracted isolation, and so on. So after the Korean War ended, the US instituted a program that was originally targeting just elite Air Force members, who might be captured by governments, you know, sh0t down and captured by governments that don’t respect the Geneva Conventions. And so the program was called Survival Evasion Resistance Escape. It was the SERE program, and the SERE program, which was first for the Air Force, but then it expanded to all four branches of the military, was designed to train US soldiers to withstand certain kinds of torture techniques, waterboarding, and other kinds of techniques. And so after 911, the idea was to quote-unquote, “re-engineer” those SERE techniques to actually have authorized US, CIA, and military interrogators to use the tactics that had been identified by the government as torture tactics that, US soldiers had been trained to try to withstand. And so the SERE tactics were really the framework for the violent and degrading tactics that were then authorized first for the CIA, and then for the military.

Josh Hoe

And at the center of that, the people who came up with the SERE, that’s Bruce Jessen and James Mitchell, is that right?

Lisa Hajjar

Right. They were the two psychologist contractors. So they had been SERE trainers, that was their big claim to fame was that they had run a SERE training program. So they trained US soldiers to withstand these kinds of tactics. So when the CIA decided to hire them early, very early on after the start of the war on terror, when the CIA was already planning to embark on its own rendition, detention, and interrogation program. And so these two psychologists, James Mitchell and Bruce Jessen, sort of went through all the SERE techniques and then proposed those within the larger collection of techniques that they thought would be most effective for interrogating alleged terrorists that would be in CIA custody. And so a number of those techniques were then approved. And then Mitchell and Jessen basically ran the CIA’s black-site torture program.

Josh Hoe

And is there a way to quickly go through the different forms? I know you kind of generalize, but I just want to get people, I want people to understand what we were actually doing.

Lisa Hajjar

Okay. So it would be, you know, a number of the most physical techniques would include waterboarding in which someone is strapped to a board with their head, their feet slightly higher than their head, a cloth is placed over their face, and they’re completely bound on this board. And then water is poured onto the cloth on their face. So the cloth intensifies the sensation that they’re being drowned like they are actually being drowned. So that was one technique. Other techniques would be, like I said, protracted isolation, or nudity, other forms of, you know, sort of humiliating techniques. But also another physical technique is walling, and that was one was very popular with Mitchell and Jessen where, as they ended up practicing it, they would bind a towel around a detainee’s neck and the towel will be attached to some kind of a rubber cord, and then the detainee would be smashed into the wall, and then jerk back through the towel was like pulled up, so they’d hit the wall and then be jerked back so that Walling, the effect of Walling was to create sort of an intense shock, as well as physical pain. So those were, you know, some of the main techniques that were used in the black sites, and again, those techniques that were approved for the CIA, in August of 2001, with the sort of blessing of the Justice Department’s Office of Legal Counsel, and specifically, someone who was in close to Cheney, someone named John Yoo, who was the Deputy Assistant Attorney General in the Office of Legal Counsel from 2001 to 2003. And so he was the guy who would write the legal memos, basically sanctioning the kinds of practices that Cheney and his own legal counsel David Addington favored so that those tactics were given their legal blessing in a memo dated August 1, 2002, for the CIA. Now, the CIA is a civilian agency. So the CIA isn’t bound by the Geneva Conventions. I mean, the CIA, we can talk about the CIA till the cows come home. But the military is bound by the Geneva Conventions, although the idiots around Cheney thought that the President had the power to just decide not to abide by the Geneva Conventions. So that approval that was authorized for the CIA was then turned, by the White House, over to the Pentagon, and Secretary of Defense Rumsfeld seized upon it. And then basically, that became the basis for the approval of torture technique techniques at Guantanamo. And then, of course, those techniques, as we know, then migrate to, they both were sort of being practiced in Afghanistan and Guantanamo. And then they ended up migrating to Iraq after the US government invaded Iraq in March of 2003.

Josh Hoe

And do we have any idea approximately – obviously, we will never probably know the total truth – how many people were detained and interrogated?

Lisa Hajjar

By the military, it’s like 10s and 10s of 1000s of people. I mean we do know, from between Afghanistan and Iraq, that’s like 10s, or even 100,000 people. I believe that the number of people who were disappeared into CIA black sites, or somehow caught up in the CIA program, I believe the total number because that was the basis of the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence’s investigation that started in 2009, I believe there were 119 people, ultimately, who were held by the CIA in black sites, and there were 780 people – that was the total number of people detained at Guantanamo. But you know, really 10s of 1000s, in Afghanistan, and in Iraq.

Josh Hoe

And so is there anything to distinguish between the kinds of facilities where people were kept in, in a sense, what caused one detainee to be kept at one facility and another person at a different kind of facility? Why were some people Gitmo and some people in Egypt?

Lisa Hajjar

Well, that’s a good question. So there’s three parts. And so one is that the CIA thought itself equipped to identify who would be the high value terror suspects, so they were basically going not after the Taliban foot soldiers or whatever, they were trying to figure out who were the real terrorist masterminds or people who knew about terrorist networks and so on. So they were basically trying to go after those that they assumed would have very valuable information. And so the people that were captured by the CIA, like one place, they would be held in black sites. And there were about, I believe, 11 black sites, which are basically secret prisons in other countries that the CIA itself ran. So we know that in Europe the CIA had black sites in Romania, Lithuania and Poland, and then they had them elsewhere. There was this black site in Morocco, there were several black sites in Afghanistan. That’s one place. But those black sites were really, there’s a variation in what the black sites were like. But the question of why, the third dimension of the CIA’s rendition, detention, and interrogation program, RDI program, is the rendition. And so it was decided to give some people, it was decided that some people that the CIA either wanted or had, they would send either his own country, where local interrogators could, you know, perhaps get information that American interrogators couldn’t get or, you know, specifically countries that have notorious records of torture. So the US War on Terror was reliant on the torture by other regimes. And so Egypt was one of the popular spots where people would be rendered into Egypt, tortured by Egyptian interrogators until they said something that might be of value, and then they’d be shipped back to the CIA into CIA [custody in] Morocco, Jordan . . .

Josh Hoe

So part of this is because we had these techniques that we were using, but we had allies that were known for going farther. And so in some of these places, if we wanted to send someone to really get, we would send them to one of those places. Is that right?

Lisa Hajjar

Absolutely, yes.

Josh Hoe

That’s disturbing. I guess I knew that. But it’s still disturbing to hear. Your book, though, is really about how the legal and in some cases, academic people, opposed to the torture programs started to rise up. And these people were opposed to the people in favor of torture. And they were in a battle over what the law means. Can you talk about some of what you learned from being a witness to this kind of conflict? And we’ll talk a lot more specifically about it, but just kind of an overview real quick.

Lisa Hajjar

Okay. So my book, you know, it’s written for general readers. So it sort of traces and tells the stories of this long fight against torture. But you know, early on, I mean, it was no coincidence that the people who were really making policy, Cheney, and his legal counsel David Addington, they surrounded themselves with a small group of right-wing lawyers, because in a fashion similar to what I was suggesting about Israel when a country regards itself as a liberal democracy, there’s some need to justify what is being done in terms of through the law, even if the law is completely misinterpreted and twisted into unrecognizable forms. But so when they did many of the policies that were instituted early on, the first one was the idea of being able to hold terror suspects incommunicado. And all of these were rationalized by lawyers like it was sort of rationalized as a kind of legal prerogative of the President to do these kinds of things. And so the first real significant development in all of this was in November, on November 13, 2001, when President George W. Bush issued a military order and that military order had actually been written by David Addington, and basically that was the order in which he decreed that anyone taken, any foreigner taken into US custody overseas would have absolutely no rights, that they would, they could be held incommunicado. They could not challenge their detention or their treatment in any court anywhere. And it was also that November 2001 order that Bush’s decrees, the existence of military commissions for those people that the US government might want to prosecute in the future. And so that was a very significant thing. And some lawyers, you know, who were, like human rights lawyers and others who read the reporting about this military order, were getting concerned. But then it was when Guantanamo was selected as the main site for long-term detention and interrogation. It was selected on December 26, 2001. And the first detainees were airlifted from Afghanistan to Guantanamo – that’s the US Naval base on the south side of Cuba – on January 11, 2002. And it was basically said that these people were going to be detained incommunicado so the public could not know who they were or how they were being treated. And that was really the trigger for the first very small group of lawyers who basically decided to fight the Bush administration. And they didn’t know what was happening at the time or how people were being treated. But they basically challenged the President’s authority to have the power to secretly detain anyone at Guantanamo. And so that was really the first legal challenge and in that case, they did find the names of a couple of people because they were the citizens of US allied countries. So three of the people whose names these lawyers, Michael Ratner, was the president of the Center for Constitutional Rights. He was really the driving force in this and he was joined by two death penalty lawyers, Clive Stafford Smith, and Joe Margolis. And so they did know the names of a couple of British citizens, one of whose names was Rasul. And so when they filed this first case, just challenging the President’s authority, the case was called Rasul v. Bush. And so that was really the first legal challenge. But so you asked, why was it, lawyers? I mean, because the US government was framing what it was doing somehow within the legal rights of the President or of the state, it required that they asserted a kind of legal rationale, and it takes a lawyer to fight a legal rationale. So that’s one of the big takeaways in my book is that it had to be lawyers, because of the way these policies were framed, it had to be lawyers fighting the legal interpretations of the State. And so that case was really the opening salvo of what I then described throughout the book as the war in court.

Josh Hoe

Well, maybe it has to be lawyers, but we were in a time then where basically almost nobody in Congress stood up against this, against Iraq or Afghanistan, where, you know, the Patriot Act, and other things were passed almost unanimously. And, you have these attorneys, you know, you’ve got the government saying, These are the worst of the worst, we’ve been attacked, you know, there’s massive emotion on the side of doing whatever is necessary to protect our country. And so, I mean, these are, this is not an easy choice for these lawyers. So, I mean, is there something, is it just that there’s a certain contrarianism? Or is it that they just believe so much in the ideas that they’re defending? Or what, as you’ve known some of these people, what was your feel of how they got to the place where they were some of the only people standing up against the government doing these things?

Lisa Hajjar

Well, I would say that that’s an excellent question, but one thing is that the policies that were instituted, I mean, the United States has many, many dark chapters in its history. But the policies that were instituted by the Bush administration were unprecedented, particularly secret detention, and coercive interrogation techniques, those things, I mean, the United States government has engaged in that kind of behavior. But it had never been really authorized as policy before. And so, I mean, just the first thing, that the idea that the government can secretly detain people and not give them any right to challenge their detention, like, what if it’s the wrong guy, you know, that goes that is like one of the cornerstones of liberal legalism. You know, it originates with the Magna Carta, the idea that habeas corpus, a regime cannot secretly detain people. And so the fight began as a fight to defend this bedrock legal principle of habeas corpus, like that was one of the …. and in fact, you know, many of the events that ensue, and the way in which more lawyers got involved, was when that particular case Rasul v. Bush, it loses in the lower courts, because, you know, US courts are just not inclined, or had no experience, thinking critically and realistically, about a policy the executive branch had authorized that had no precedent in US history. So the courts were just like, we’re just going to dismiss these cases. But when it did get, Rasul v. Bush did get to the Supreme Court, you know, Michael Ratner and his band of rule of law defenders won. And so that is one of the major events that because and there’s many other things that occur right in the build-up to that June 2004 Supreme Court decision, but that’s when hundreds of lawyers, who just have become angry at what they were learning about what the government had done, including the secret authorization of a torture policy, that’s when you get hundreds of lawyers volunteering to represent Guantanamo detainees as habeas counsel.

Josh Hoe

What’s interesting there is, I think I want to talk about this a little bit, is the notion that it’s really not … we may believe, you may believe the law means something, I may believe the law means something. The lawyers you’re talking about, on one side believe the law means something. The lawyers on the other side, either believe or [are] bad faith actors arguing that the law means something. And this kind of reminded me and I think, to some extent, the book maybe is about this is, many decades ago, I think back in the 80s when I first came into contact with this, was this notion in critical legal studies called the indeterminacy thesis. And Michael Dorf explained it as: “If the application of a rule requires deliberation about its meaning then the rule cannot be a guide to action, the way that a commitment to the rule of law appears to require. Similarly, if the content of a constitutional right or other constitutional provision can only be determined by extensive deliberation, then the Constitution does not enrich rights or other principles in the sense of providing foundational assurances. Indeterminacy opens the way to judicial discretion. And both the law and the Constitution are meant to be the master of those in authority, not the servant of their caprice.” And I think in this instance, it’s kind of an example of where we have hopes for what the law represents. But the law can technically be all of these things in a way. I think people like Dick Cheney, John Yoo, and other people in the Bush administration, what they were doing with torture, and to some extent later, what Trump and Bannon were doing to democracy, is explicitly exposing the indeterminacy at the heart of our law, and trying to exploit it. I know this is a really long question. Is it really just a matter of interpretation? And who is doing the interpretation? Is there, can we believe that there’s a core of law that is true that there’s something determinate at the heart of law? I mean, it seems like we want to believe that, at least the people who are arguing against torture want to believe this, but I’m not entirely sure that’s true. Maybe it is. Maybe it’s not. What do you think?

Lisa Hajjar

Well, that’s an excellent question, again, it’s an excellent question. But there are two things that are absolutely and incontrovertibly true. Torture is absolutely a non-derogable, right? that no one under any circumstances, anywhere has a right to torture. So any efforts to I mean, the government did you know, the US government didn’t say, we have the right to torture, they said torture is bad, but waterboarding does not rise to the level of torture, therefore, it’s not torture. So but torture is categorically. I mean, when I write about this, you know, torture is my thing. So I basically say the right not to be tortured, is along with the right not to be enslaved, the most universal right that human beings have. Because absolutely, under no circumstances, does anyone have a right to torture, and every single human being has an absolute right not to be tortured or enslaved.

Josh Hoe

So that’s not entirely true, because the Constitution creates an exception for slavery in the 13th amendment for people who are incarcerated, but yes . . .

Lisa Hajjar

Yes, exactly. I mean, that can be some of the civil slavery. But the other, sort of bedrock thing, as I’ve mentioned before, was that secret detention is unacceptable under all circumstances because it violates habeas corpus and habeas corpus is basically the idea that the state can be limited by law. But what Cheney and the circle of radical right-wing lawyers around him were pushing was another legal interpretation. They were basically latching on to this thing called the unitary executive thesis, which is a right-wing understanding of presidential power based on Article Two of the Constitution, and basically saying that you know, Cheney and those around him believed that it would be unconstitutional. So they’re making a constitutional argument that any effort to limit or restrict the President’s discretion on matters of national security or foreign affairs would be unconstitutional. So in other words, whatever the President wants to do, must be legal because of the nature of his power under the Constitution. And therefore, that was their effort to negate the applicability of the Geneva Conventions and other laws. So it’s like a legal argument to open up space to do illegal things.

Josh Hoe

That makes me think of two things. The first thing is that if it’s true, that if they had won the argument that the unitary executive theory was true if the courts had upheld that, would that not then bring into question the premise that torture absolutely can’t be done because the President can just imagine it away. It didn’t win the day in this instance. But it does seem to be an example of what I’m talking about, about the indeterminacy of law, that there are contradicting impulses within the Constitution, that may indeed mean that the emperor has no clothes at the heart, if that makes sense?

Lisa Hajjar

Well, I mean, so one of the things, you know, since I’m not a lawyer, myself, but one of the things that I learned, you know, through the process . . .

Josh Hoe

I like to play one on podcasts.

Lisa Hajjar

When I was doing research, and really when I was looking at the efforts, there were multiple efforts, and all of them failed. I mean, there were a couple of cases in the War in Court that were won, and that really changes the course of things. But the cases that were brought to either try to pursue accountability – torture is a crime. It’s an international crime, it’s a gross crime, you know, it’s a crime under US law. So when there were efforts to prosecute or rather sue, in US courts, those people who were responsible for the torture program, or to pursue justice for victims of US torture, the courts, it wasn’t that the Court said, Oh, torture is fine. But every single one of those cases failed, for reasons that are, you know, tied into how the US legal system works. In other words, that, you know, certain people, you know, who are trying to sue the government would lack standing or that the issue is a political issue that’s non-justiciable. So the courts basically didn’t weigh in on some of the questions like, are these interrogation tactics a violation of the law, they basically dismissed the lawsuit so that the cases couldn’t even be argued. So in some ways, you know, what the kinds of policies, the Bush administration instituted, even though the torture policy is over, our legal system has been so damaged because there was never a legal cleanup. There were, the lawyers I write about stopped certain things through their legal challenges. But there’s been no, you know, significant cleanup. I mean, I would say, that’s not completely true. I mean, the military did, with the active involvement of the late Senator John McCain, who was himself a torture victim from the Vietnam War. He, once he, you know, came to understand in 2004-2005, what had been authorized for military interrogators, he basically passed, you know, got an amendment and passed a law, and it’s now been instituted, basically taking the military out of the coercive interrogation business. So the military has cleaned up its house a bit.

Lisa Hajjar

Well the CIA is beyond hope.

Josh Hoe

But I think this is another example of where you could just move the deck chairs, if an administration wants to move to, just doesn’t want to have the military do it, have someone else do it, then that’s kind of what they were doing at black sites. And then, one other thing about indeterminacy I wanted to ask, is, while it may be true that torture is non-negotiable as a concept, what constitutes torture seems to still be a Moveable Feast, or at least to the, as you call them, far-right lawyers. It was a Moveable Feast. And essentially, they said, Whatever we’re doing doesn’t mean what torture, the definition of torture is.

Lisa Hajjar

I mean, that particular, the tail of that memo goes back to John Yoo, as I’ve mentioned, who, by the way, is a distinguished professor at Berkeley Law School. So what John Yoo did, and I’m sure he had other people sort of weighing in on this as well, but in order to basically provide legal cover for those re-engineered SERE techniques, he basically conceived of the idea that torture is a vague concept, but what does it mean, you know, when the United States ratified the Convention Against Torture, they did provide certain kinds of understandings of how the convention would be interpreted in the United States. And so basically, the way in which, the definition of torture was intentionally causing severe physical pain or prolonged mental harm. So then John Yoo basically just said, Well, what constitutes severe physical pain? and then basically argued that the kinds of things that US CIA interrogators wanted to do did not rise to that level, because the way in which he defined it was severe mental pain is equivalent to pain, comparable to organ failure or even death. So anything, any pain that would be less than that would be not torture. And if it’s not torture, it’s not illegal, you know, which also ignores the fact that cruel, inhumane, and degrading treatment is also illegal. But you know, so you get these people who were pursuing their own ideological wish fantasies, but they had the role of being government lawyers in the Office of Legal Counsel. And so when they write this crazy nonsense in memos, it actually has the function of law, because you know, Office of Legal Counsel memos are supposed to be, the OLC is the government’s lawyer.

Josh Hoe

So let’s, for a second, I’m gonna try to put my hat on, like I’m at least trying to see things from their perspective, which is very hard for me to do. It’s not where I’m at. But there are two sides to this, though. They’re the people who did nothing wrong, who were arrested and tortured, a lot more of them than the other kind. And then there’s the people who were at least theoretically involved in terrorism and were tortured, to get information. But it doesn’t seem like these justifications address the moral cost of arresting a lot of people and torturing those who didn’t do anything. Was there any point in this where the Bush administration, or any of their people or organs or whatever, made any concessions to the fact that they might have harmed innocent people?

Lisa Hajjar

Oh, well, I mean, no, there’s never been any official apology. You know, the closest the government came was in 2014, when Obama, President Obama was like, Oh, we did a lot of things right. But we tortured some folks. You know, that’s hardly an accounting. But I mean, the living enduring proof of the damage that torture did to the very interests United States government claims to be defending is the fact that the 911 case, which involves five people who are accused of having played various roles in the planning of 911, one of whom is Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, who was the alleged mastermind of 911, he was evil, he and the other four were held, along with others in the CIA black sites for years. And then, when the Supreme Court issued a ruling brought by a military lawyer that challenged the government in the case of Hamdan V. Rumsfeld, that case was decided by the Supreme Court in June of 2006. And the Supreme Court said, Guess what, Common Article Three of the Geneva Conventions applies to everyone in US custody. And so it was that decision in 2006, it forced the Bush administration reluctantly to empty the black sites. And so then they brought 14 people including Khalid Sheikh Mohammed and the other four people who are charged with responsibility for 911 to Guantanamo, and then they tried to put them on trial. That case, you know, 911 happened in 2001, it’s 2023. That case was stuck in pre-trial. First of all, it failed once; it collapsed. And then they were rearraigned in 2012. And for 20 years, the case was in pre-trial, negotiate pre-trial status, because of the fact that they had been tortured by the CIA, so the government that tortured them is seeking to execute them. And, you know, it’s just, that was a failure. Now, that case is involved in plea bargain negotiations. And so if the government had wanted to actually try and execute people responsible, to prove them guilty in a court of law, they completely screwed themselves by having tortured them. But this goes back to Cheney, this goes back to Cheney’s ignorance and hubris, I mean, he believed that whoever the CIA had, those people would never see the light of day again, the idea was almost like, this is where we come back to the Phoenix Program scenario like you’re gonna torture the hell out of them, you know, get whatever information you can and then just permanently disappeared them, meaning kill them or whatever. And it was really a shock, when the people who, you know, you get these 14 people who are transferred from CIA custody to Guantanamo, in 2006. And now the CIA is on the hook for what they did with these people. But it was that transition. And this is one thing I don’t go into detail my book but I begin with the argument, the reason the US government’s strategic approach to the war on terror shifts from capture, interrogation, and detention, to targeted killing, that is extrajudicial execution, was because of the fact that they could no longer hold people, disappear people and torture people in secret because of these various legal cases that had kind of precluded those options. And so then targeted killing escalates in Bush’s last year in office and then expands exponentially under Obama and then continues under Trump.

Josh Hoe

I remember reading the Senate report when it came out. And we talked about this a little bit already, but one of the conclusions was that the information gained through torture is pretty close to entirely unreliable. I think that’s correct. I mean, I know that the story you mentioned in the book is the classic ticking time bomb that, you know, was kind of the premise of the whole series 24. You know, are we likely to ever gain the code from anything – like I’m playing devil’s advocate to some extent – through torture? Is there any evidence that suggests that torture is effective?

Lisa Hajjar

No, absolutely not. If you don’t know the answer, or if you’re not able to get someone to offer a true answer – and you do that through rapport-building techniques or other lawful interrogation techniques – if you don’t know what the answer is, people can say anything. And that’s what the CIA torture program proved was that so many false statements were made under torture, and then the government didn’t know whether those were true or false. Like, you know, there’s plans to blow up the Brooklyn Bridge, or, you know, Al-Qaeda is converting Black Muslims in Montana, you know, it’s like black Muslims in Montana, and when they send off people to try and investigate these things that came out as a result of torture, and there was the Senate Select Committee’s report really documents that there was nothing that came of a positive nature of the CIA torture program, and many damaging and harmful things were the result of that torture program.

Josh Hoe

And one of the harmful things, I think, is that the signal we send by doing this tells the rest of the people in other countries, in essence, that that’s fair game, right? I mean, it puts our citizens and soldiers at risk in the same way that their citizens and soldiers were put at risk. Is that fair? Or is there any deterrent value?

Lisa Hajjar

That’s absolutely fair. This is why JAGS, Judge Advocate Generals when they found out what was happening, it was a kind of the secret, clandestine move to authorize torture. And then also then, when John McCain, who was on the Armed Services Committee, which is responsible for the well-being of the military, realized that, you know, this would be extraordinarily dangerous to US soldiers in future wars. It would also but one thing that was learned from the lessons of Vietnam, that Cheney obviously took the wrong lessons from, was when, a military is fighting without abiding by laws and rules, it causes chaos and dissension in the ranks, I mean, like the phenomenon of fragging during the Vietnam War, where soldiers would basically kill their commanding officers, because it’s like, if there’s no rules, and everybody can be killed, and there’s no sense of what the limits are, what the guidelines are, it actually degrades the military itself. So it was like, pure damage. And anybody – and this is one of the things that I’m not, I believe there are many issues in life where indeterminacy applies, but I basically feel that anybody who thinks that torture works is an idiot, doesn’t know what they’re talking about, has not paid attention. Lacks the basic ability to discern reality from fantasy. And so this is one of those things where I feel like we are standing on very solid ground with this one.

Josh Hoe

So we get no actionable intelligence. If anything, it puts our citizens and soldiers at risk abroad. And, on top of that, there were a lot of innocent people, we talked about, you said earlier, like 10s of 1000s of people, approximately how many of those people who were detained and tortured or interrogated – whatever you want to, they want to call it – were actually factually innocent? It was a fairly large percent, yes?

Lisa Hajjar

Yes. I mean, absolutely. Because, you know, what happened at the beginning of the war on terror? The United States didn’t know who was who, or what was what. And so, they’re in Afghanistan and people, the government was, the military was offering massive bounties. And so people would turn in their enemies like that, you know, this guy, his sheep, were eating my grass, and I’m gonna turn him in. So anybody who ended up in interrogation in Afghanistan at the beginning of the war, you know, was presumptively a terrorist, that was sort of what the interrogators were told, presume that these people are lying, presume that if they land in Bagram, you know, despite the fact that they were sold for bounty, or whatever, that they’re going to be guilty. And then decisions were made in Washington very early on when Guantanamo was selected, to decide that every non-Afghan who was captured in Afghanistan would be sent to Guantanamo and the presumption, again hubristic ignorance, was that the only reason foreigners would be in the country was because they were terrorists. And so every non-Afghan plus then lots of Afghans who were members of the Taliban, et cetera. But, you know, I mean, first of all, some of the people that were characterized by the government as high-value detainees, that’s one thing, you know, but then to then try and prosecute them in a military commission, the government had to completely reinvent the idea, like, I mean, there’s a very basic and utterly ludicrous idea. And we can see this happening, the fate of the military commissions, the idea that non-soldiers can be prosecuted for violations of the laws of war, that first of all, is crazy, because non-soldiers are not subject to the laws of war, but then also turning non-war crime offenses into violations of the laws of war in order to prosecute them in the military commission. So turning conspiracy into a military offense or turning attempted murder into a war crime, that’s not what a war crime is.

Josh Hoe

But this was just another attempt for them to stop being in regular courts right?

Lisa Hajjar

Absolutely.

Because they’d all been tortured, but it’s like the military commissions, you know, in totality, the cases that have survived, are two, in 20 years, like several of the cases, there were only like three cases were prosecuted during Bush’s time in office, I think, six or seven were prosecuted, in Obama’s, every single one of them, except one case, was actually thrown out once the appeals court got to weigh in, like in 2016 and 17 on and said, Yeah, you know, what, these things are not actually prosecutable offenses. And so those sentences were vacated. So I mean, the whole thing has been just one giant waste of time. But coming back to your question about like, people who are innocent, I mean, you know, so one, Hamdan, Salim Hamdan, whose case, you know, sort of ends, you know, brings an end to the torture program. He was some poor Yemeni who’d gone to Afghanistan, as many people would do because his brother-in-law had encouraged him to go there. And his brother-in-law gets him a job as Osama Bin Laden’s driver, he’s a poor guy driving some, he gets captured after 911, November of 2001. And then they turn him into, the government, when they want to prosecute him in the military commissions, turn him into this terrorist mastermind, the prosecution attempted to link this, you know, Yemeni guy Salim Hamdan to 911, and the 1998 Al-Qaeda bombings of embassies in Africa, and it failed; the military jury that ruled on his case, basically, was like, no we don’t think so. Maybe one, you know, they gave him one charge, they convicted him on one charge of material support for terrorism, which isn’t a war crime. And found him not guilty of all the other charges.

Josh Spector

You were present for some of the legal proceedings. And I have to ask because I don’t know if I’ll ever get to talk to anyone else who was involved (although one of the lawyers who talked about I do know) what were some of the most surreal moments for you? It had to at times been very strange.

Lisa Hajjar

Well, so let me say just to put this in context, my book, the War in Court is written really in the first person because like, I’m sort of writing about . . . . . So I started as soon as these legal challenges started, I started interviewing lawyers and once lawyers started going to Guantanamo, as habeas counsel, I would interview them, but I couldn’t, I assumed I couldn’t go to Guantanamo. I couldn’t write a National Science Foundation grant for $30,000, in order to go and conduct research on what’s happening at Guantanamo. And it was very frustrating. So my research was all based on interviews of people out of one of the contexts I was studying, and then in 2010, you know, I was really frustrated because it was that was Obama, the first person that the Obama administration decided to prosecute was a child soldier, sort of breaking global tradition of not prosecuting child soldiers since World War Two. And so a friend of mine, who was an expert witness for the case of Omar Khadr, we were talking before one of the hearings, I was like, Oh, I wish I could go, she said you could go if you went as a journalist. So I was like ding I write journalistically. So that was really the opening for me to be able to go to Guantanamo. I go as a journalist, I do write journalistically, so I was there for the last three hearings of the Omar Khadr case, and then most of the other cases since 2013, that I’ve gone to, I’ve been to Guantanamo 14 times. So most of those trips were to observe and report on the 911 case. And I’ll tell you, the 911 case, I mean, as I said, it’s been going on for years. But one thing that happens is every time there is a hearing, there’ll be journalists who would come down, NGO observers, and then there would also be victims, for the people, the family members of victims of 911, there’s a lottery that they could put in a bid to be able to go down and be observers of the case. So there’s always the victim family members, you know, along with the journalists and NGO observers sitting in the gallery, the soundproof gallery in the back. And so the event that really comes, bring comes to mind about the strangest moment was when the lawyer for Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, and he’s like the icon of both 911, because he’s the alleged mastermind, and the CIA torture program because he was waterboarded 183 times. I mean, his treatment was the most intense. So, you know, one of Khalid Sheikh Mohammed’s lawyers was basically talking about the brain scan that they had conducted on him and the other people, there was an MRI, an MRI machine had been brought to Guantanamo. And this lawyer, Gary Sowards, the lead counsel, was saying that there’s evidence that Mohammed suffered brain damage as a result of his treatment in the black sites because he’d been walled repeatedly. And in fact, that was one of the things that when Mitchell and Jessen, Mitchell testified, he said that the only thing that really worked on Khalid Sheikh Mohammed was walling him. And so then the lawyer is making the connection between what the CIA did to Khalid Sheikh Mohammed. And he says, and this might force the government to take the death penalty off the table, or even throw out the charges because of outrageous government treatment. And all the victim family members are – because this is the guy that they, you know, for those who endorsed the death penalty, hearing that their aspiration to see the person who haunts their nightmares getting off because the government tortured him was like, a shocking moment, you know, for people.

Josh Hoe

When I was incarcerated, it became very clear to me how thin the line really is sometimes, between what we see as our free life, and the life that can quickly turn into incarceration, or in this instance, torture, or military disappearance, or things like that. Did you ever have moments when you are going through security and things like that, where you saw the thinness of that line?

Lisa Hajjar

I mean, for me personally, no. I want to say that sort of having cut my teeth in Israel and Palestine, it takes a lot to really get me scared.

Josh Hoe

Not scary as much as just that they’re, you know …

Lisa Hajjar

You can see it. But, the only thing I’ll say is, I can see it for other people, but at least vis a vis going to Guantanamo, you know, rather than that thin line. I mean, the worst thing that can happen to a journalist is if they do something that violates the rules, and then they can get shipped off the island. I mean, that’s really the worst thing that would happen. But it’s very infantilizing, like the way in which journalists, they have their minders, and so it’s like being under surveillance, but I personally didn’t find myself in any kind of danger. And the one thing I would say that I just really want to give a shout-out to, you know, Carol Rosenberg, who’s been reporting on Guantanamo since those first people were flown in on January 11 2002. And she’s still down there for every military commission hearing. Everything, almost everything we know about Guantanamo, especially in the more recent years, when media coverage has dissipated, we know because Carol Rosenberg reported it, and she has learned so much and is such a master of what is permissible, what’s not permissible, and she’ll push it, like being on a media delegation with Carol Rosenberg is like having a white knight guarding you along the way.

Josh Spector

So even early on, we saw some domestic application of these ideas. There was the case of Ashcroft versus Iqbal, I know they’ve moved on, which is arguably not a good thing, but certainly not a good thing to the people who are targets, many of whom are civilians, but to targeted executions. How safe though, should people in this country feel? And are there precedents that could be applied domestically in other ways? Like, for instance, you know, in the case of the Ashcroft versus Iqbal, someone was, he was a foreign national, but a lot of these techniques were used in a regular federal facility in my understanding. Do you think there’s any overlap or anything bled from the . . .

Lisa Hajjar

Well, I think that the kind of extralegal violence that police interrogators might use or, you know, any other security, domestic security forces, to utilize the kind of tactics that were authorized for offshore interrogations has to be done extralegally, at least now, but I mean, it does happen. I mean, in the sense that police, for example, the scandal of your 22 decades of Chicago police torture, you know, that kind of thing like those tactics, what happens then, is that the violent and illegal and brutal techniques that might be used are not necessarily legal. But if the system is incapable of holding people criminally accountable for those things, then for all intents and purposes, it’s de facto legal. So there’s a lot of de facto legalism. I just think, you know, that the damage that was done to assert the government’s right to do the things that were done in the war on terror has emboldened people like Donald Trump and others to feel as though the executive branch should be unfettered by oversight, and so on. So many of the contemporary domestic travails that this country is going through can trace their roots back to the policy and legal developments in the war on terror. And the War on Terrorism isn’t over as long as Guantanamo is open. And the reason Guantanamo, one of the reasons why Guantanamo continues to be open and must stay open, is because Congress passed legislation in 2011, or 2010 or 11, basically barring any person who’s ever been at Guantanamo, including those who are still at Guantanamo, from coming into the United States for any reason whatsoever, you know, including trial or detention. And the reason why they’re in Guantanamo is because what was done to them, would never fly in the United States. And even if Congress lifted that thing, what was done to the people who remain at Guantanamo, the 35 people, and there’s only about 11 of them that are slated for military, the five 911 people, and a few others who are slated for prosecution is because they would be they couldn’t be tried in federal courts, because of what the government did to them. I mean, there’s federal standards, and so on. So it’s just a very messy and unresolved set of issues. This is one thing I tried to argue in the book is just to help people really understand with a sense of clarity and a broad view of what actually happened, how the law or lawyers responded, or how the courts did or failed to respond in certain ways. In order, if in the future, another occasion when there might be the temptation to just throw all legal standards and norms to the wind in order to justify security policies that are flatly illegal, that maybe this book might be one of the resources people would look to, to say, oh, yeah, we really shouldn’t go down that road, because it was a disaster. We tried it last time.

Josh Hoe

Yeah, I know, we struggle a lot with similar pressures in the criminal justice world, like you’re talking about, something just terrible happens, you know, there’s anecdotal, terrible, you know, something really bad happens. And people kind of immediately move past what everyone maybe thought were core principles. And in the call, the rush to kind of a brutal response to try to get justice or information or whatever it is. After studying all of this, have you come to any conclusions about the way we can or should counteract these kinds of impulses, which seem somewhat natural because they happen over and over and over again, you can see them through history where, you know, something terrible happens, people essentially throw their principles out the window and then we have to deal with situations like this.

Lisa Hajjar

Yeah. I mean it raises, this is something that I’ve really struggled with as a citizen, and also as a scholar, in terms of dealing with these kinds of issues, but you know, there are aspects of US American political culture, and we see them playing out now where, it’s very vivid with, like, there is no longer consensus opinions about what is true, or, you know, that even the idea that human beings deserve certain kinds of, you know, that was a long fought centuries-long battle to just, you know, recognize the humanity of humans, and that was so easily dissipated with the surges of anti-immigrant rhetoric and, the fact that a significant portion of Americans now, would, you know, you know, bemoan the cancellation of the torture program, and would like to have it restored, and so on. So we have something like torture or all of these contralegal policies, you know, they, to the extent that they are authorized by governments and endorsed by influential figures, be they politicians or pundits, it seeds support for them within society, and our society is so sort of at odds with itself over what is true, what is right, what is necessary, that, it’s like, torture is just a manifestation of a different problem, you know, in American society that goes much more deeply into what’s wrong with us.

Josh Hoe

So let me try a different way of seeing if there’s a solution. You conclude the book suggesting that the law might not be enough, that for torture and other things that we were talking about to never happen again, we would have to have a political reckoning. Do you have any theories about how people might be moved to put things like human rights before exceptionalism? How do we have that political reckoning?

Lisa Hajjar

I think I say this in my book, or at least I think it is a theme that education, knowledge, and understanding are vital. And so for people to educate themselves and understand history, so it doesn’t repeat itself. You know, I think that education is absolutely crucial. And it is for that reason, that education is seen by those who don’t want to accept realities or complex truths, etc. – why education is in the crosshairs. And so if one just even looks at, for example, the assault on what the right-wingers think critical race theory is, critical race theory, emanates out of a kind of legal rationale of the structures and legal processes that have entrenched and sustained even as they’ve altered, racial disparities in society, not a radical position is kind of empirically obvious, but like having that be . . .

Josh Hoe

One would think empirically obvious. And we’ve discussed CRT many times.

Lisa Hajjar

The fact that this is in the crosshairs of people who are literally anti-intellectual. And so one way I think about it is like the intellectuals versus the anti-intellectuals. And so people should just be intellectuals because that is what I think is crucial for pushing back against the most horrific and ignorant policies and practices.

Josh Hoe

I agree with you, in a sense, but I’m not sure that the most effective political strategy is to say, okay, all of you who disagree with us, you’re anti-intellectual, and we’re the intellectual.s

Lisa Hajjar

Even if you take the simple issue or more simple issue of critical race, you see people basically on the news who are experts on critical race theory, talking about what it is, and then you see people who are combating them, making up things. So I’m not a politician. So I don’t want the political solutions, but I do feel that education, knowledge, awareness, sort of realistically grounded consciousness, those are all essential tools for a functioning democracy.

Josh Hoe

Yeah, one would think so. And, I push people on these kinds of questions, not because I think that there’s necessarily an obvious answer because if there were, we wouldn’t be in the situations we’re in. But just to see what people come up with. I always like to ask people if there’s any criminal justice or criminal justice adjacent books that they like and would recommend to our listeners; do you have any favorite books? Aside from obviously your own book, which you can feel free to plug it again.

Lisa Hajjar 1:09:40

I definitely hope that people will pick up my book, it’s called the War in Court: inside the long fight against torture. If you go to my Twitter, @lisahajjar, the pinned tweet at the top has a code so you can order the book from the University of California Press for a 30% discount. I mean, one thing I’d say is that this is based on 20 years of research, I don’t think there’s any book that does what I do. I mean, it’s really a 20-year accounting of what happened in the course of the war on terror. . . .

Josh Hoe

Just so people know, I was trying to get to the major themes, but you do a pretty exhaustive timeline from the very beginning to the end of going through all of the legal challenges, and what happened. And you know, I think if I had tried to go that route, it would have been a four-hour interview.

Lisa Hajjar

Well, that’s why it took me 20 years to write the book. But the books I would recommend, I mean, one of them, it’s just such a powerful book, is written by a former Guantanamo detainee, Mohamedou Ould Salahi. And so while he was still in prison, his lawyers, it took them years, they had to fight the government in court for years, to get his letters to them cleared and they were heavily censored. While he was still at Guantanamo his book was published called Guantanamo Diary, he is a beautiful writer. He’s authored many other books. He was finally repatriated back to Mauritania. And then he and the guy, Larry Siems who had worked on the first book, they joined forces. Larry Siems is the director or one of the directors of PEN, you know, the writers’ association for freedom of speech. And so they issued in 2017, a Guantanamo Diary restored edition in which they basically filled in all the stuff that had been redacted in the earlier version. And the perfect complement to that – I mean, really, like I love movies, I see every movie ever made, but the best War on Terror movie is the movie based on Salahi’s life, The Mauritanian, and so Jodie Foster plays Salahai’s lawyer Nancy Hollander, and Benedict Cumberbatch plays the military prosecutor who was, you know, assigned to prosecute Salahi and then comes to realize how brutally he was tortured and the case falls apart, but The Mauritanian is absolutely a fantastic movie and to Tarik Rahim plays Salahi. And then another book by another Guantanamo detainee who now is living in Serbia. It’s Mansoor Adayfi, Don’t Forget Us Here. That’s Mansoor Adayfi’s account and what makes Adayfi’s autobiography so interesting is he really writes about Guantanamo as a place, like the detention facility. And it’s really I mean, I know that a couple of my political geography friends found that book interesting, just because of the kind of geographical imagery that he’s able to capture. And it’s also beautifully written. And then the fourth book I would recommend to people is written by the late great Michael Ratner. It’s his autobiography that was published posthumously called Moving the Bar, My Life as a Radical Lawyer. So that’s a really powerful autobiography. And, you know, Ratner was at it from the Attica rebellion up to, the fights against torture at Guantanamo. So his life is very eventful.

Josh Hoe

I always ask the same last question, what did I mess up? What questions should I have asked, but did not? There doesn’t have to be an answer to that. But if you have one, I always like to hear what people would have liked to talk about that I missed?

Lisa Hajjar

Oh, I think well, hopefully, your listeners will get a little bit of a sense, I mean, the one thing I would simply add is that I think and maybe you can agree or disagree that the book is, its written in a style, like of stories, you know, so while we’re talking about these complex issues like unfettered executive power, there’s a lot of people, there’s a lot of characters in the book, a lot of the happiness and the tragedies that affect them in this so I think that’s something that I hope . . .

Josh Hoe

It’s definitely not a dry read. It’s definitely, there’s a lot of life in there.

Lisa Hajjar

Right. That’s it I think.

It’s been a pleasure talking with you.

Josh Hoe

Thanks so much. It was a great pleasure to have you on the podcast.

And now my take.

Why did I choose to cover rendition, detention, and torture to start the season? Because whenever and wherever people are incarcerated, I am interested in discussing and investigating what has happened. I also feel that if there’s one larger center or heart to this whole podcast, it’s the notion that people, no matter who they are, or what they have done, should always first be treated with the same level of dignity as any human being. In a sense, this is a human rights podcast. It’s about a lot of things. But first and foremost, it’s about the idea that everyone should be treated with human dignity.

I’m excited to be back for a sixth season of the podcast. I took a bit of a longer break than I usually do getting ready for this season. But I have some really exciting interviews lined up and I hope you’ll tune in and check it out throughout Season Six. I also hope everyone’s having a wonderful Martin Luther King Day. If you remember back to the very first episode of this podcast, it’s very intentional that I choose to start everything, every single season, on Martin Luther King Day.

As always, you can find the show notes or leave us a comment at decarcerationnation.com. If you want to support the podcast directly, you can do so from patreon.com/decarceration nation. For those of you who prefer to make a one-time donation, you can now go to our website and make a one-time donation. Thanks to all of you who have joined us from Patreon or have given a donation. You can also support us in non-monetary ways by leaving a five-star review from iTunes or add us on Stitcher, Spotify, or from your favorite podcast app. Make sure and add us on social media and share our posts across your networks. Also, thanks to my employer, Safe and Just Michigan for helping to support the DecarcerationNation podcast. Remember, it takes a village to promote a podcast. Thanks so much for listening to the DecarcerationNation podcast. See you next time.

Decarceration Nation is a podcast about radically re-imagining America’s criminal justice system. If you enjoy the podcast we hope you will subscribe and leave a rating or review on iTunes. We will try to answer all honest questions or comments that are left on this site. We hope fans will help support Decarceration Nation by supporting us on Patreon.